The Illusion of Progress in Complex Query Answering

In the field of Artificial Intelligence, one of the holy grails is complex reasoning. We don’t just want machines that can recognize a cat in a picture; we want systems that can navigate complex chains of logic to answer questions that require multiple steps.

In the domain of Knowledge Graphs (KGs), this task is known as Complex Query Answering (CQA). For years, researchers have been developing neural networks that map queries and entities into latent spaces, aiming to solve intricate logical puzzles. If you look at the leaderboards for standard benchmarks like FB15k-237 or NELL995, it looks like we are making incredible progress. Accuracy is going up, and models seem to be mastering reasoning.

But a recent paper, “Is Complex Query Answering Really Complex?”, drops a bombshell on this narrative. The authors argue that our perceived progress is largely an illusion caused by the way we build benchmarks. It turns out that the “complex” queries we are testing our AI on are effectively “easy” questions in disguise, allowing models to cheat by memorizing training data rather than learning to reason.

In this post, we will deconstruct this research, explain why current benchmarks are flawed, and look at the new, truly challenging standards proposed by the authors.

Background: Knowledge Graphs and Logical Queries

To understand the flaw, we first need to understand the task. A Knowledge Graph (KG) is a structured way of storing data using entities (nodes) and relations (edges). For example, a triple might look like (Spiderman 2, distributedVia, Blue Ray).

The Goal of CQA

CQA involves answering First-Order Logic questions over these graphs. These aren’t simple lookups; they involve logical operators like conjunction (AND), disjunction (OR), negation (NOT), and existential quantification.

Consider the following natural language query:

“Which actor performed in a movie filmed in New York City and distributed on Blue Ray?”

In logical terms, finding the answer (Target \(T\)) involves finding a variable \(V\) (the movie) that satisfies three conditions simultaneously:

- The movie was distributed on Blue Ray.

- The movie was filmed in NYC.

- The actor performed in that movie.

Query Types

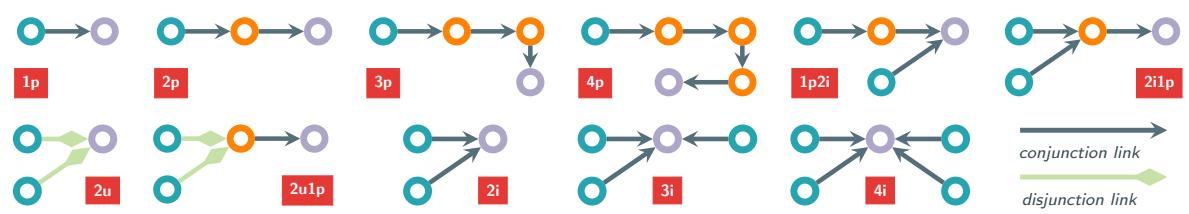

In research, these logical structures are categorized by their shape.

- 1p (One Path): A simple link prediction. Given entity A and relation R, predict entity B.

- 2p / 3p: Multi-hop paths (A → B → C).

- 2i / 3i: Intersections. Finding an entity connected to 2 or 3 other specific entities.

- 2u: Unions (Logical OR).

The diagram below illustrates these structures. Nodes are circles, and arrows are relations. “i” stands for intersection, “p” for path, and “u” for union.

The assumption has always been that a 3p query (3 hops) is harder than a 1p query, and a 2i query (intersection) requires sophisticated logic to aggregate information from different branches.

The Core Problem: The Spectrum of Hardness

The central thesis of the paper is that structural complexity does not equal reasoning difficulty.

Standard benchmarks work by splitting the Knowledge Graph into a training graph (\(G_{train}\)) and a testing graph (\(G_{test}\)). The goal is to answer queries on the test graph, predicting missing links.

However, the authors point out that in a real-world scenario (and in these benchmarks), parts of the answer path might already exist in the training data. This leads to a concept called the Reasoning Tree.

The Reasoning Tree and Reducibility

When a model tries to answer a query, it traverses a “reasoning tree” from the anchor entities (e.g., “Blue Ray”, “NYC”) to the target. The difficulty of the query depends entirely on how many links in that tree are missing (requiring inference) versus how many are observed (existing in the training data).

If a “complex” query is composed mostly of links the model has already seen during training, the model doesn’t need to perform complex multi-hop reasoning. It can “short-circuit” the logic.

Let’s look at a concrete example using the query discussed earlier:

As shown in Figure 1:

- Top Case (Full Inference): To find the answer “A. Serkis”, the model must predict the link from Blue Ray to King Kong, and from NYC to King Kong, and from King Kong to A. Serkis. All links are missing (dotted lines). This is a Hard query.

- Bottom Case (Partial Inference): To find “K. Dunst”, the model sees that “Spiderman 2” is already linked to “Blue Ray” in the training data (solid line). The model doesn’t need to infer that relationship; it just looks it up. The complex “2i1p” query effectively collapses into a simple “1p” (link prediction) query from Spiderman 2 to K. Dunst.

The authors formally define this distinction:

- Full-Inference Pair: A query/answer pair where the reasoning tree consists entirely of links found only in the test set. The model must reason over unseen data for every step.

- Partial-Inference Pair: A pair where at least one link in the reasoning tree exists in the training set.

The Shocking Statistics

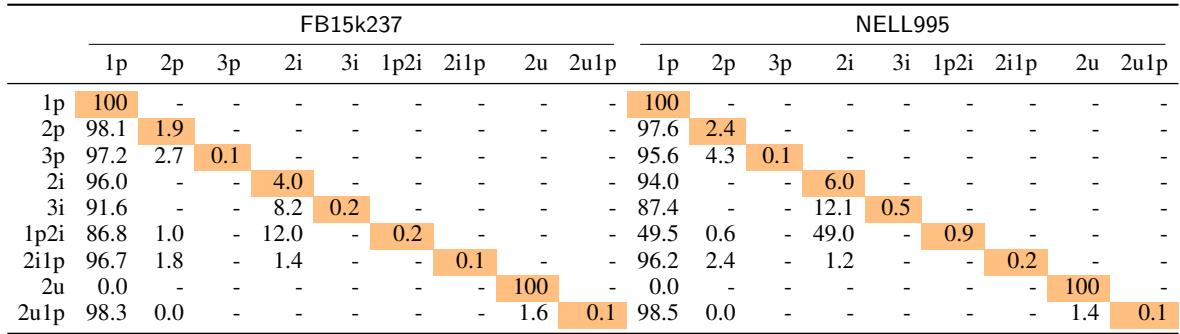

If benchmarks were balanced, we would expect a mix of these. However, the authors analyzed the popular datasets FB15k237 and NELL995 and found a massive imbalance.

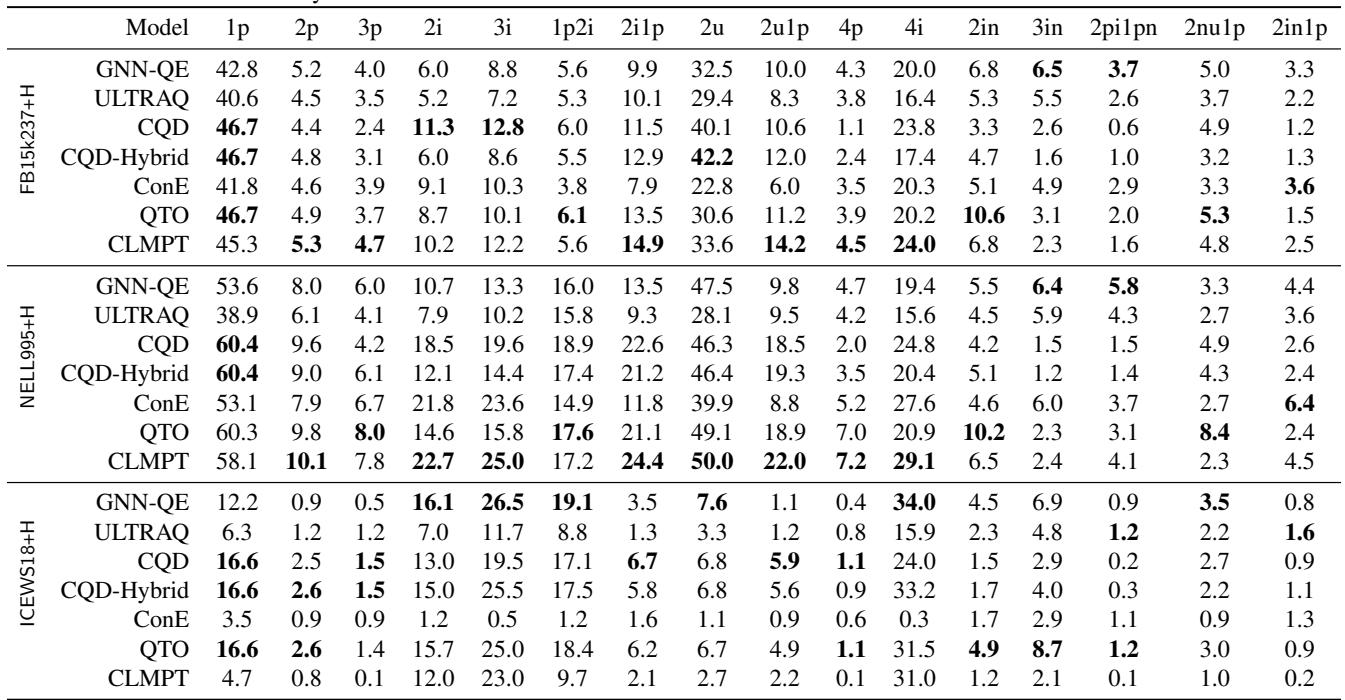

Table 1 reveals the extent of the problem. Look at the column “1p” for FB15k237.

- For 2p queries, 98.1% can be reduced to simple 1p queries.

- For 2i1p queries, 96.7% can be reduced to 1p.

- For 3p queries, 97.2% can be reduced to 1p.

This means that for the vast majority of “complex” queries, the model only needs to predict one single missing link. The rest of the path is memorized from the training set. We aren’t testing complex reasoning; we are testing simple link prediction wrapped in a complex wrapper.

Why Current Models Perform “Well”

The prevalence of partial-inference queries explains why current State-of-the-Art (SoTA) models have high scores. Neural networks are excellent at memorizing training data. If a model can memorize \(G_{train}\) and perform decent single-hop link prediction, it will ace these benchmarks without ever needing to perform multi-hop reasoning.

To prove this, the authors experimented with a “cheat” model called CQD-Hybrid.

The CQD-Hybrid Experiment

CQD (Continuous Query Decomposition) is an existing neural method. The authors modified it to create a hybrid solver that:

- Uses a standard neural link predictor.

- Explicitly memorizes the training graph. If a link exists in \(G_{train}\), it is assigned a maximum score (perfect probability).

If complex reasoning (inferring missing paths) was truly required, this simple heuristic shouldn’t help much on the hard test set. But because the test set is full of “reducible” queries, CQD-Hybrid achieves State-of-the-Art results, outperforming complex, dedicated reasoning architectures like Transformers and Graph Neural Networks on the old benchmarks.

This confirms the hypothesis: High performance on current benchmarks is driven by memorization, not reasoning.

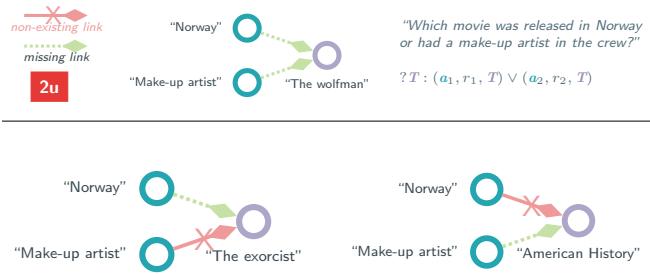

The Union (OR) Fallacy

The paper also highlights a critical flaw in Union (2u) queries. A union query \(A \lor B\) is satisfied if either condition A OR condition B is met.

As shown in Figure 3, the authors found that in many benchmark queries, one of the branches (e.g., the path to “The Exorcist”) relies on a link that does not exist in the graph at all (neither train nor test).

If one branch of an “OR” query is impossible, the query effectively becomes a simple 1p query on the valid branch. The authors found that filtering out these broken queries (retaining only those where both branches are theoretically possible) significantly changes the perceived difficulty.

The Solution: New Benchmarks (+H)

To measure actual progress in AI reasoning, we need benchmarks that cannot be solved by memorization alone. The authors introduce three new datasets:

- FB15k237+H

- NELL995+H

- ICEWS18+H (A temporal knowledge graph)

The "+H" stands for Hard (or perhaps Honest).

How They Were Built

The key innovation in these benchmarks is balancing. The authors explicitly sampled queries to ensure an equal distribution of “easy” (reducible) and “hard” (full-inference) queries.

- For a 3-hop query type, the benchmark contains an equal number of pairs that reduce to 1-hop, 2-hop, and full 3-hop inference.

- They filtered out the broken Union queries.

- They added truly deep query types: 4p (4-hop paths) and 4i (4-way intersections).

ICEWS18+H: A Realistic Challenge

Most benchmarks split data randomly. The authors argue this is unrealistic. In ICEWS18+H, they used a time-based split. \(G_{train}\) contains events from the past, and \(G_{test}\) contains events from the future. This makes memorization much less effective because the structures in the future might evolve differently than in the past.

The Verdict: SoTA Models Struggle

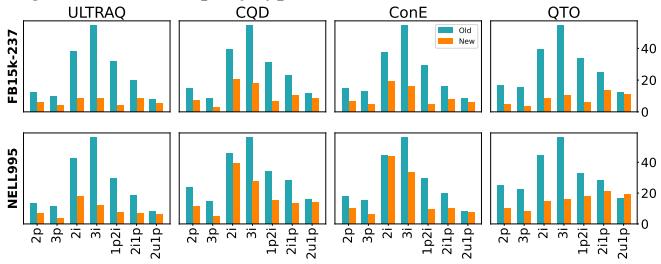

When the authors re-evaluated current top models (like GNN-QE, CQD, and Transformer-based models) on these new benchmarks, the results were stark.

Figure 4 visualizes the collapse in performance.

- Blue Bars (Old Benchmarks): High performance, suggesting mastery of reasoning.

- Orange Bars (New Benchmarks): Performance plummets.

For example, on 3i (3-way intersection) queries in FB15k237, performance (MRR) dropped from roughly 54.6 down to 10.1.

Detailed Analysis

The stratified analysis (breaking results down by query type) drives the point home.

Table 5 shows the results on the new datasets. There is no clear winner anymore. Models that dominated the old benchmarks (like QTO) struggle immensely on the new ones. The simple “1p” queries (link prediction) still see decent performance, but as soon as the queries require true multi-hop inference (3p, 4p, 3i), the scores are incredibly low—often in the single digits.

This indicates that we effectively do not have reliable methods for solving full-inference complex queries yet. The problem is much harder than we thought.

Conclusion and Implications

The paper “Is Complex Query Answering Really Complex?” serves as a necessary reality check for the Knowledge Graph community. It demonstrates that:

- Complexity is Deceptive: A query that looks complex logically (\(A \land B \land C\)) might be computationally trivial if parts of the data are already known.

- Benchmarks Matter: Biased sampling in dataset creation distorted our view of the field for years, masking the fact that models were overfitting to easy instances.

- Reasoning is Unsolved: On the new, balanced benchmarks (+H), current neural methods fail to perform robust multi-hop reasoning over missing data.

By adopting these new benchmarks, the research community can stop chasing inflated scores on easy questions and start addressing the real challenge: building AI that can truly reason over incomplete knowledge, rather than just memorizing it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/10624_is_complex_query_answeri-1622/images/cover.png)