Introduction

Clustering is one of the most ubiquitous tasks in machine learning and data science. Whether you are segmenting customers for a marketing campaign, identifying communities in a social network, or grouping genes with similar expression patterns, the goal is always the same: partition data points so that similar items are in the same group and dissimilar items are separated.

Standard techniques like Spectral Clustering rely purely on the intrinsic structure of the data—represented as a graph where edges denote similarity. But what happens when you know more? In many real-world scenarios, we possess domain knowledge. We might know for a fact that two specific data points must belong to the same cluster (a “Must-Link” constraint) or that two points cannot be in the same cluster (a “Cannot-Link” constraint).

Standard spectral clustering struggles to incorporate these rigid constraints naturally. This leads us to the Constrained Clustering Problem.

In this post, we will explore a research paper that proposes a mathematically elegant solution to this problem: CC++. By modeling constraints as a second graph and utilizing a concept called the Signed Laplacian, the researchers developed an algorithm that is not only numerically stable and fast but also comes with strong theoretical guarantees via a Cheeger-type inequality.

Background: Graphs and Laplacians

To understand the solution, we first need to establish the vocabulary of graph theory used in this context.

We start with a standard weighted undirected graph \(G = (V, E, w)\). Here, \(V\) is the set of vertices (data points), \(E\) represents connections, and the weight function \(w\) tells us how strong those connections are.

The Standard Laplacian

The engine behind spectral clustering is the Graph Laplacian. If you are familiar with calculus, the Laplacian operator measures the divergence of the gradient—essentially how smooth a function is over a surface. On a graph, it measures how smooth a function (signal) is over the vertices.

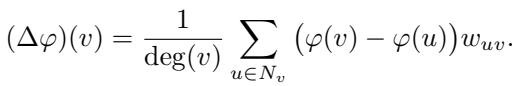

The standard weighted Laplacian operator \(\Delta\) acts on a function \(\varphi\) defined on the vertices. It is defined as:

Here, \(\deg(v)\) is the weighted degree of vertex \(v\). Intuitively, this operator compares the value of the function at a node \(v\) with the weighted average of its neighbors.

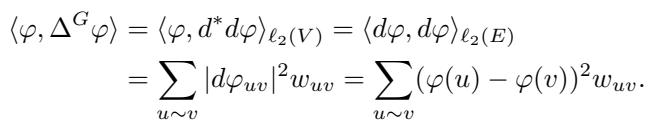

The “smoothness” of a map over the graph can be quantified by the quadratic form associated with the Laplacian:

Notice the term \((\varphi(u) - \varphi(v))^2\). This value is small when connected vertices \(u\) and \(v\) have similar values. Spectral clustering minimizes this quantity to find cuts that separate the graph without breaking strong connections.

The Signed Laplacian

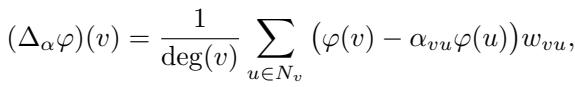

The paper introduces a twist: the Signed Laplacian. What if edges could have negative signs? A “signature” maps edges to either \(+1\) or \(-1\). The Signed Laplacian, denoted as \(\Delta_{\alpha}\), is defined as:

If \(\alpha_{vu} = 1\) for all edges, we get the standard Laplacian. If \(\alpha_{vu} = -1\), we get the signless Laplacian. This flexibility becomes crucial later when we need to tweak our constraint graph to ensure the math works computationally.

The Core Method: Constrained Clustering via Ratios

formulating the Problem

The authors model the problem using two graphs on the same set of vertices:

- Graph \(G\): Represents the data similarity (the standard graph).

- Graph \(H\): Represents the constraints. An edge in \(H\) represents a “Cannot-Link” constraint (or a demand for separation).

The goal is to find a subset of vertices \(S\) that minimizes a specific ratio. We want to make a cut that slices through very few edges in \(G\) (preserving similarity) but slices through many edges in \(H\) (satisfying separation constraints).

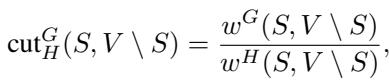

The Cut Ratio is defined as:

Here, \(w^G(S, V \setminus S)\) is the weight of edges in \(G\) crossing the cut, and \(w^H(S, V \setminus S)\) is the weight of edges in \(H\) crossing the cut.

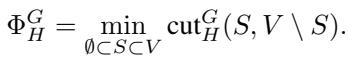

The objective is to find the set \(S\) that minimizes this ratio:

The Computational Challenge

Finding the optimal discrete cut is an NP-hard problem. However, in spectral graph theory, we relax these discrete problems into continuous eigenvalue problems.

The authors derive that this specific ratio cut is related to a Generalized Eigenvalue Problem. We look for eigenvalues \(\lambda\) and eigenvectors \(x\) that satisfy relations between the Laplacian of \(G\) (\(\Delta^G\)) and the Laplacian of \(H\) (\(\Delta^H\)).

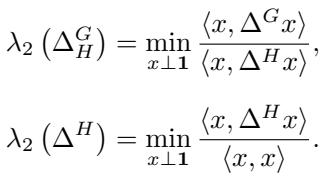

Specifically, the optimal cut is bounded by the spectral properties of these two operators:

The Cheeger-Type Inequality

One of the paper’s major theoretical contributions is establishing a Cheeger-type inequality for this constrained problem. In classical spectral clustering, Cheeger’s inequality guarantees that the cut found by the eigenvector is not arbitrarily far from the true optimal cut.

The authors prove a similar guarantee for the constrained case. If we perform a “sweep-set” procedure on the eigenvector (ordering vertices by their value in the vector and checking every possible split), the quality of the resulting cut \(\Phi_H^G\) satisfies:

This is a powerful result. It tells us that by solving the spectral problem, we are guaranteed a certain level of performance relative to the true optimal solution.

The CC++ Algorithm: Fixing the Singularity

There is a practical snag. In the inequality above, we see \(\lambda_2(\Delta^H)\) in the denominator. If the constraint graph \(H\) is disconnected or sparse (which it often is), its Laplacian \(\Delta^H\) might be singular (not invertible) or have a zero eigenvalue that causes division by zero issues.

This is where the Signed Laplacian saves the day.

The authors propose adjusting the graph \(H\) to create a new graph \(H'\). They add a negative self-loop to a specific vertex in \(H\). Wait, a negative loop? This sounds counter-intuitive, but mathematically, using the Signed Laplacian allows this.

By adding a self-loop with a negative weight and using the signed Laplacian \(\Delta_{\alpha}^{H'}\), the operator becomes invertible (positive definite). The problem transforms into solving the following generalized eigenvalue equation:

This specific formulation is the heart of the CC++ algorithm.

- Efficiency: Because \(\Delta_{\alpha}^{H'}\) is invertible and symmetric positive definite, we can use efficient solvers (like Cholesky decomposition) rather than the slower QZ algorithm required for general matrices.

- Stability: It avoids the numerical instability of dividing by near-zero numbers.

- Theory: The paper proves that this modification preserves the spectral properties enough that the Cheeger inequality still holds.

Experiments & Results

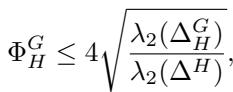

The researchers tested CC++ against standard Spectral Clustering (SC) and a previous version of constrained clustering (CC) without the signed Laplacian improvements.

Synthetic Data: Stochastic Block Models

They generated graphs using a Stochastic Block Model (SBM) with two communities. They varied the “inter-cluster probability” \(q\). As \(q\) increases, the two clusters blend together, making them harder to distinguish.

Interpretation: Look at Figure 1 above. The yellow line (SC) drops rapidly as the noise (\(q\)) increases. Standard spectral clustering fails when the groups aren’t clearly separated. However, the blue line (CC++) maintains high accuracy (ARI \(\approx 0.6\)) even when the clusters are very noisy (\(q=0.18\)), proving that the constraints help guide the algorithm through the noise.

Scalability and Speed

Is this method slow? Adding constraints usually adds complexity.

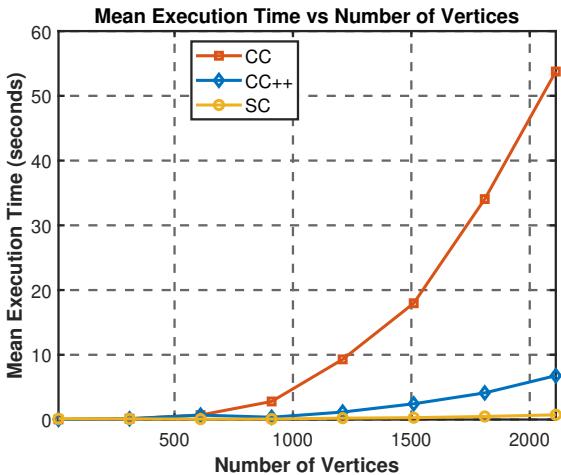

Figure 2 shows the execution time. The red line (the old CC method) skyrockets as the number of vertices increases. The blue line (CC++), however, stays very close to the yellow line (Standard SC). This confirms that using the signed Laplacian with the negative self-loop allows for highly efficient solvers, making constrained clustering scalable.

Visualizing the Difference

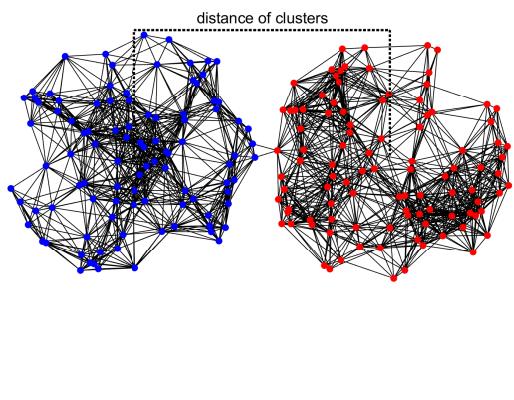

To visualize how the algorithm handles overlapping data, they used Geometric Random Graphs where two clusters physically overlap in space.

The results were stark:

- Standard SC fails completely when clusters overlap (ARI drops to 0).

- CC++ maintains high accuracy because the “Cannot-Link” constraints in graph \(H\) tell the algorithm, “Even though these points are close in space, they belong to different groups.”

Real-World Application: Temperature Data

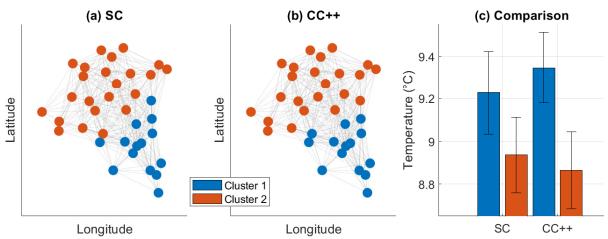

The authors applied CC++ to weather station data in Brittany, France.

- Graph G: Constructed based on geographical proximity (stations near each other are connected).

- Graph H: Constructed based on temperature difference (stations with very different temperatures are connected in \(H\), representing a “separation” constraint).

The Result:

- Figure 5a (SC): Simply cuts the map in half based on geography.

- Figure 5b (CC++): Creates a more nuanced cluster. It groups stations that are geographically close and share similar temperature profiles.

- Figure 5c: Shows that CC++ successfully separated the stations into distinct temperature regimes (no overlap in error bars), whereas the SC clusters had significant temperature overlap.

Conclusion

The research presented in “Signed Laplacians for Constrained Graph Clustering” offers a robust step forward for machine learning practitioners dealing with side information. By formalizing constraints as a second graph and minimizing the cut ratio, the method respects both the data structure and user knowledge.

The true innovation, however, lies in the Signed Laplacian. By cleverly modifying the constraint graph with a negative self-loop, the authors turned a computationally difficult and unstable problem into one that can be solved as efficiently as standard spectral clustering.

Key Takeaways:

- Constraints Matter: When data is noisy, purely structural clustering fails. Constraints (Must-Link/Cannot-Link) provide the necessary guide rails.

- Ratios are Powerful: Formulating the problem as minimizing the ratio of cuts in \(G\) vs. cuts in \(H\) is mathematically sound.

- Signed Laplacians solve Singularity: The introduction of negative weights (signatures) allows for invertible operators, unlocking faster and more stable algorithms (CC++).

For students and practitioners, this paper illustrates beautiful interplay between linear algebra (eigenvalues), graph theory (cuts), and practical algorithm design. It reminds us that sometimes, a small mathematical “trick”—like a negative loop—can yield significant performance gains.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/11451_signed_laplacians_for_co-1653/images/cover.png)