In the world of machine learning, bigger is often better. Training massive models requires massive amounts of data and compute power, leading to the widespread adoption of distributed learning. We split the work across hundreds or thousands of workers (GPUs, mobile devices, etc.), and a central server aggregates their results to update a global model.

But there is a catch. In scenarios like Federated Learning, the central server has little control over the workers. Some workers might be faulty, crashing and sending garbage data. Worse, some might be malicious “Byzantine” attackers, intentionally sending mathematically crafted gradients to destroy the model’s performance.

To counter this, researchers have developed Byzantine-Robust Distributed Learning (BRDL). The core idea is simple: instead of trusting every worker, the server uses “robust aggregators” (like taking the median instead of the average) to filter out outliers.

It sounds like a perfect solution: built-in defense systems that keep the model safe. But a recent research paper, “On the Tension between Byzantine Robustness and No-Attack Accuracy in Distributed Learning,” uncovers an uncomfortable truth. These defenses are not free.

When there are no attackers—which is often the case—using these robust tools can actively hurt the model’s accuracy. In this post, we will dive deep into this research to understand the fundamental tension between being safe and being accurate.

The Setup: Distributed Learning and the Threat

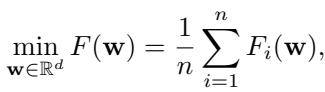

Let’s start with the basics. In a standard Parameter Server framework, we try to minimize a global loss function \(F(\mathbf{w})\). This function is usually the average of the loss functions \(F_i(\mathbf{w})\) calculated on each worker \(i\)’s local data.

In a trusted environment, we solve this using Gradient Descent (GD). In every iteration \(t\), the server broadcasts the current model parameters. Workers calculate their local gradients \(\mathbf{g}_i\), and the server updates the model using the simple average of these gradients:

However, the simple average is incredibly fragile. A single Byzantine worker can send a gradient with an arbitrarily large value (e.g., infinity), shifting the average completely off course and ruining the model.

Enter the Robust Aggregator

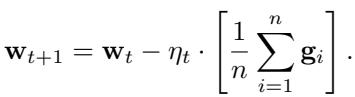

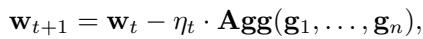

To fix this, BRDL replaces the simple average with a Robust Aggregator, denoted as \(\mathbf{Agg}\).

Common examples of these aggregators include:

- Coordinate-wise Median: Taking the median value for each parameter.

- Trimmed Mean: Removing the largest and smallest values before averaging.

- Krum / Geometric Median: Selecting updates based on spatial geometry.

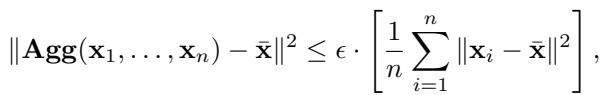

These methods are designed to tolerate up to \(f\) malicious workers out of \(n\) total workers. Mathematically, existing literature defines an aggregator as \((f, \kappa)\)-robust if it satisfies a specific inequality:

Essentially, this definition ensures that the aggregated result is close to the “true” mean of the honest workers (\(\bar{\mathbf{x}}_S\)), bounded by a constant \(\kappa\).

The Core Problem: The Price of Robustness

The paper poses a critical question: What happens if we turn on these defenses, but nobody attacks us?

In a scenario with no Byzantine workers, the “true” update should be the average of all workers (\(\bar{\mathbf{x}}\)). However, robust aggregators are designed to ignore or downweight outliers. In distributed learning, “outliers” aren’t always bad—they might just be honest workers who happen to have unique, diverse data distributions (heterogeneous data).

If a robust aggregator discards valid gradients because they look “different,” it introduces an aggregation error.

To quantify this, the authors introduce a new metric called \(\epsilon\)-accuracy. This measures how far the aggregator deviates from the true mean when everyone is honest.

Here, \(\epsilon\) represents the “cost” of the aggregator. A perfect aggregator (like the simple mean) would have \(\epsilon = 0\) in the absence of attacks. But as we will see, robust aggregators typically have \(\epsilon > 0\).

The General Lower Bound

The authors prove a significant theoretical result: You cannot have high robustness without high error.

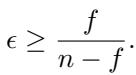

If you want an aggregator to tolerate \(f\) Byzantine workers, it must have a worst-case error proportional to that tolerance. Specifically, the paper proves that for any robust aggregator:

This is a profound finding. The fraction \(\frac{f}{n-f}\) grows as \(f\) increases.

- If you assume 0 attackers (\(f=0\)), the error lower bound is 0.

- If you want to tolerate nearly half the network being malicious (\(f \approx n/2\)), the lower bound for error shoots up towards 1 (meaning the error is as large as the variance of the data itself).

This inequality mathematically formalizes the “tension” mentioned in the title. By preparing for more enemies (\(f\)), you inevitably degrade performance when no enemies show up.

Analyzing Specific Aggregators

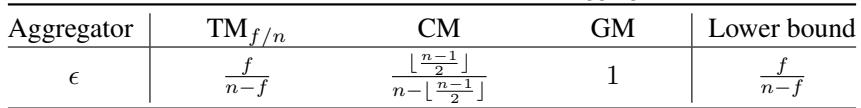

The researchers didn’t just stop at a general bound; they analyzed three specific, popular aggregators to see how they perform against this theory.

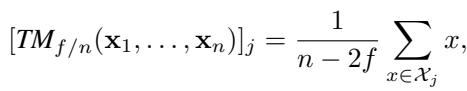

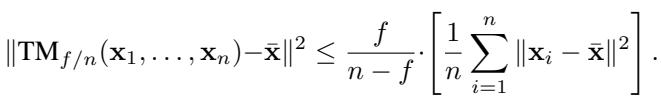

1. Coordinate-wise Trimmed Mean (\(TM_{f/n}\))

The Trimmed Mean operates by removing the largest \(f\) and smallest \(f\) values for each coordinate, and averaging the rest.

It intuitively makes sense that ignoring the tails of the distribution would introduce error if the data is skewed. The authors proved that for Trimmed Mean, the accuracy parameter \(\epsilon\) is exactly:

Notice that this matches the general lower bound perfectly. This implies that Trimmed Mean is, in a sense, optimally robust—but it still suffers from the inevitable error floor defined by \(f/(n-f)\).

2. Coordinate-wise Median (CM)

The median is an extreme version of the trimmed mean (trimming almost everything).

The analysis shows that the median has a much higher \(\epsilon\). While robust, it discards so much information from honest workers that its error in no-attack scenarios is very high.

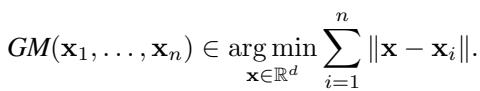

3. Geometric Median (GM)

The Geometric Median finds a vector that minimizes the sum of Euclidean distances to all input vectors.

The paper proves that the Geometric Median is 1-accurate (\(\epsilon = 1\)). This is quite high compared to Trimmed Mean (when \(f\) is small), indicating substantial information loss in benign settings.

Summary of Error Bounds

The table below summarizes the findings. We can see that \(\epsilon\) (the no-attack error) is distinct from \(\kappa\) (the robustness constant).

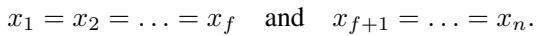

When is the Error Worst?

The theory provides a “worst-case” bound. But what does that worst case look like?

Through their proofs, the authors identified the conditions that maximize aggregation error. For the Trimmed Mean, the error is maximized when the data distribution is highly skewed. Specifically, if \(f\) workers are clustered at one extreme and the remaining \(n-f\) workers are at the other extreme:

This reveals a connection to Data Heterogeneity. In distributed learning, if all workers have identical data (IID), their gradients will be identical, and the robust aggregator will output the same value as the mean. However, in real-world scenarios (Non-IID), workers have different data. This creates skewness in the gradients.

Key Takeaway: The tension between robustness and accuracy is amplified when data is heterogeneous. The more diverse the data, the more “honest outliers” exist, and the more the robust aggregator mistakenly suppresses them.

Impact on Convergence

We know that robust aggregators introduce error in a single step. But does this ruin the entire training process over thousands of steps?

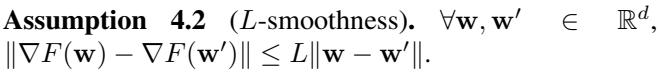

The authors analyzed the convergence of Byzantine-Robust Gradient Descent (ByzGD). They relied on standard assumptions in the field:

- L-Smoothness: The loss function doesn’t change too jaggedly.

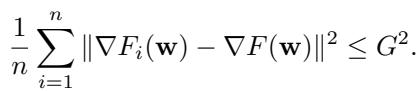

- Bounded Heterogeneity: The variation in gradients between workers is bounded by \(G^2\).

The Convergence Lower Bound

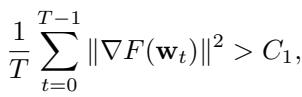

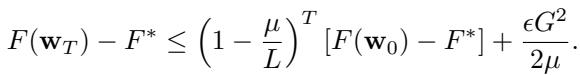

The main convergence theorem (Theorem 4.5) is pessimistic. It states that even with perfect tuning, the gradient norm (a proxy for how close we are to a solution) cannot converge to zero. It will get stuck above a certain floor \(C_1\):

Similarly, the loss function value will stay above the optimal \(F^*\):

Crucially, this error floor \(C_1\) is proportional to \(\frac{f}{n-f} G^2\).

This confirms the earlier intuition:

- Higher \(f\) (More Robustness) \(\rightarrow\) Higher Error Floor.

- Higher \(G\) (More Heterogeneity) \(\rightarrow\) Higher Error Floor.

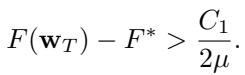

The Upper Bound

To ensure this lower bound wasn’t just a loose theoretical estimate, the authors also proved an upper bound (Theorem 4.6) for convex functions satisfying the PL-condition.

As time \(T \to \infty\), the first term vanishes, but the second term \(\frac{\epsilon G^2}{2\mu}\) remains. Since we know \(\epsilon \geq \frac{f}{n-f}\), the upper and lower bounds tell the same story: You cannot optimize perfectly if you are using robust aggregators in a heterogeneous environment.

Experimental Evidence

To back up the math, the researchers trained a ResNet-20 model on the CIFAR-10 dataset. They tested the model without any attacks to measure the pure cost of robustness.

They controlled data heterogeneity using a Dirichlet distribution parameter \(\alpha\).

- Low \(\alpha\) (e.g., 0.1): Highly heterogeneous (Non-IID).

- High \(\alpha\) (e.g., 10.0): More homogeneous (IID).

Results: Increasing Robustness (\(f\)) hurts Accuracy

The experiments tested “Multi-Krum” and “Coordinate-wise Trimmed Mean.”

In the results for Multi-Krum (shown in the paper’s Table 3, not pictured here but described), when \(f=0\) (standard mean), accuracy was ~89%. As they increased the tolerance \(f\) to 7, accuracy plummeted to ~40% in the heterogeneous case (\(\alpha=0.1\)).

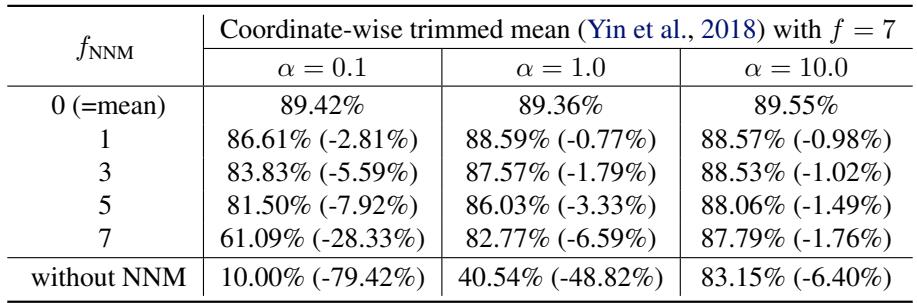

The results for Trimmed Mean (Table 4 in paper) showed a similar trend. With high heterogeneity (\(\alpha=0.1\)), increasing \(f\) from 0 to 7 caused accuracy to drop from roughly 89% to 10%.

This validates the theory: simply turning on the “defense” knob (\(f\)) destroys the model if the data is diverse, even with zero attackers present.

Can Mixing Help?

A technique called Nearest Neighbor Mixing (NNM) is often proposed to reduce heterogeneity. It mixes gradients between workers to make them more similar before aggregation.

The authors tested if this helps.

In the table above (Coordinate-wise trimmed mean with NNM), look at the column for \(\alpha=0.1\) (high heterogeneity).

- Without NNM, accuracy was effectively broken (10.00%).

- With NNM, accuracy recovered significantly (up to ~86% with \(f_{NNM}=1\)).

However, the tension remains. Using a smaller \(f_{NNM}\) improves accuracy but reduces the effective robustness of the system. Even with mitigation strategies, the trade-off persists.

Conclusion and Implications

This research acts as a reality check for the field of Byzantine-Robust Distributed Learning.

- There is no free lunch: You cannot simply maximize your defense against attackers (\(f\)) without degrading the model’s performance for honest users (\(\epsilon\)).

- Heterogeneity is the enemy: The trade-off is negligible when data is identical across workers but becomes severe in real-world, non-IID scenarios (like Federated Learning).

- Parameter Estimation is Vital: In practice, engineers must estimate the actual number of likely attackers carefully. Setting \(f\) to the theoretical maximum “just to be safe” will likely render the model useless in a benign environment.

As distributed systems become the standard for training AI, understanding this “cost of paranoia” is essential for building systems that are not just secure, but also effective.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/121_on_the_tension_between_byz-1779/images/cover.png)