In the era of GDPR, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), and increasing digital surveillance, the “right to be forgotten” has transitioned from a philosophical concept to a technical necessity. When a user deletes their account from a service, they expect their data to vanish not just from the database, but also from the “brain” of the AI models trained on that data.

This process is known as Machine Unlearning.

Ideally, when data is removed, we would simply retrain the AI model from scratch without that specific data. This is called “exact unlearning.” It works perfectly, but it is astronomically expensive and slow. Imagine retraining a massive Large Language Model or an ImageNet classifier every time a single user submits a deletion request. It is computationally infeasible.

This has led researchers to hunt for “approximate” solutions—methods that can tweak the existing model to make it act as if it never saw the data, without the heavy lifting of retraining. However, these shortcuts often come at a cost: they either degrade the model’s overall accuracy or fail to truly delete the information, leaving the model vulnerable to privacy attacks.

In this post, we will dive into a new method proposed in the paper “Not All Wrong is Bad: Using Adversarial Examples for Unlearning”. This technique, dubbed AMUN (Adversarial Machine UNlearning), uses a counter-intuitive approach: it fine-tunes the model on “wrong” data—specifically, adversarial examples—to surgically remove memories while preserving the model’s overall intelligence.

The Gold Standard: What Does “Forgetting” Look Like?

Before we can design a method to make a model forget, we need to understand what a model looks like when it hasn’t seen a piece of data.

In machine learning, we typically split data into training sets (which the model memorizes) and test sets (which the model has never seen).

- Training Data: The model is usually very confident about these samples.

- Test Data: The model can classify these correctly, but its prediction confidence (probability scores) is generally lower than for the training data.

Therefore, if we successfully “unlearn” a specific subset of data (let’s call this the Forget Set, or \(\mathcal{D}_F\)), the model should treat these samples just like it treats the unseen Test Set (\(\mathcal{D}_T\)). It shouldn’t necessarily get them wrong, but it shouldn’t be overly confident about them either.

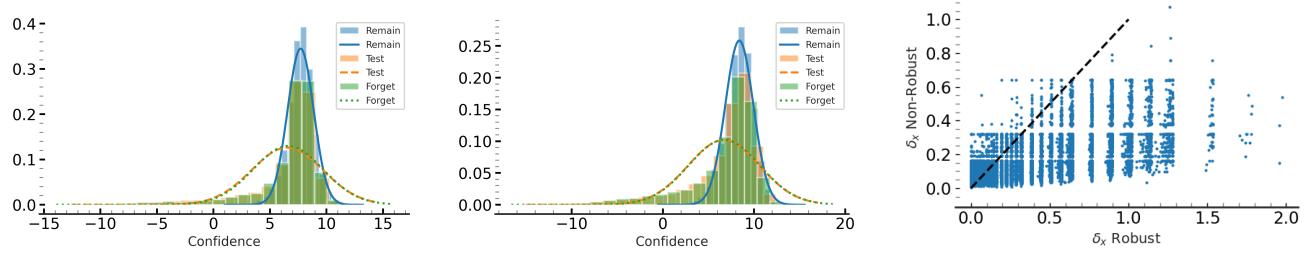

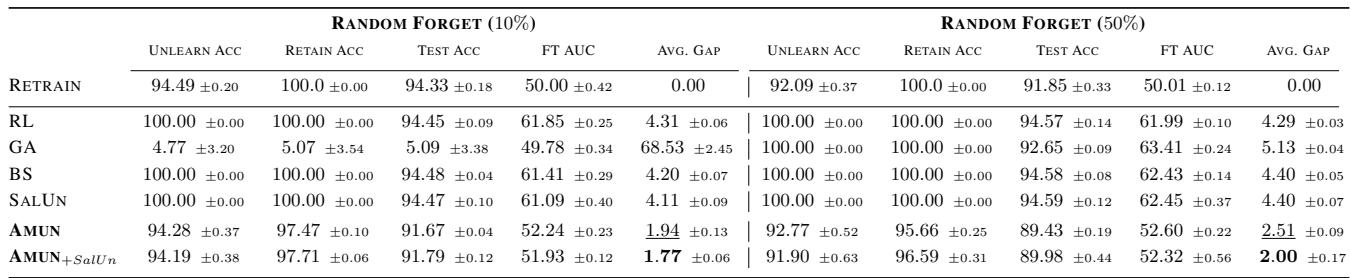

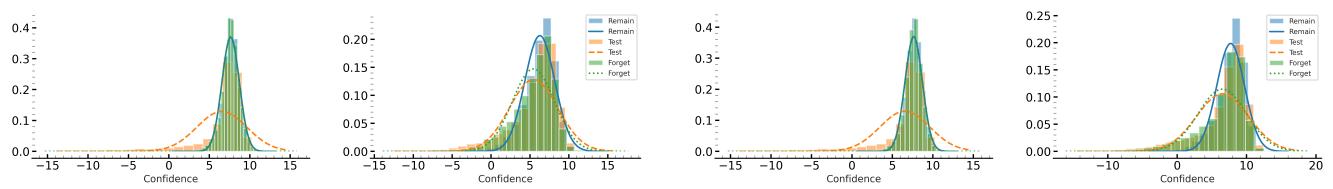

The researchers analyzed models that were retrained from scratch (the “Gold Standard”) to visualize this behavior.

As shown in the histograms above, in a retrained model, the confidence distribution of the “Forget Set” (the green bars) perfectly overlaps with the “Test Set” (the orange line). The model treats the data it was supposed to forget exactly like data it has never seen.

The Key Insight: Most previous unlearning methods try to force the model to make random predictions or maximize error on the Forget Set. This is unnatural. The goal shouldn’t be to make the model “dumb” regarding the deleted data; the goal is to make the model indifferent and less confident, aligning its behavior with the natural distribution of unseen data.

The Solution: Adversarial Machine UNlearning (AMUN)

The researchers propose a method called AMUN. The core idea relies on Adversarial Examples.

What are Adversarial Examples?

Usually, adversarial examples are considered a security threat. They are inputs (like images) that have been slightly modified—often imperceptibly to humans—to trick a neural network into making a wrong classification with high confidence. For example, changing a few pixels in a picture of a panda might make the model think it’s a gibbon.

These examples exist because deep learning models learn decision boundaries that are highly specific to the training data. An adversarial example sits just across the decision boundary.

Turning the Weapon into a Tool

AMUN flips the script. Instead of using adversarial examples to attack a model, it uses them to “heal” the model of specific memories.

Here is the logic:

- The model has “memorized” the Forget Set (\(\mathcal{D}_F\)) and is highly confident about it.

- We want to lower this confidence without breaking the model’s performance on the rest of the data.

- We generate adversarial examples for the Forget Set. These are inputs (\(x_{adv}\)) that look very similar to the original data (\(x\)) but are predicted as a different class (\(y_{adv}\)).

- We fine-tune the model on these adversarial examples using their wrong labels.

This sounds dangerous. Why would training on wrong labels help?

When the model is fine-tuned on an adversarial example (\(x_{adv}\)) with the label (\(y_{adv}\)), it is being told: “This input, which looks like the original data \(x\), belongs to class \(y_{adv}\).” However, the original model knows that \(x\) belongs to class \(y\). Because \(x\) and \(x_{adv}\) are extremely close to each other in the mathematical input space, the model is pulled in two directions. It tries to accommodate the new information (the adversarial label) while holding onto its existing knowledge (the original label).

The result is a “smoothing” of the decision boundary. The model doesn’t catastrophically forget the concept; it simply becomes less confident about that specific area of the input space. This mimics exactly what we saw in the “Gold Standard” retrained models: lower confidence on the Forget Set.

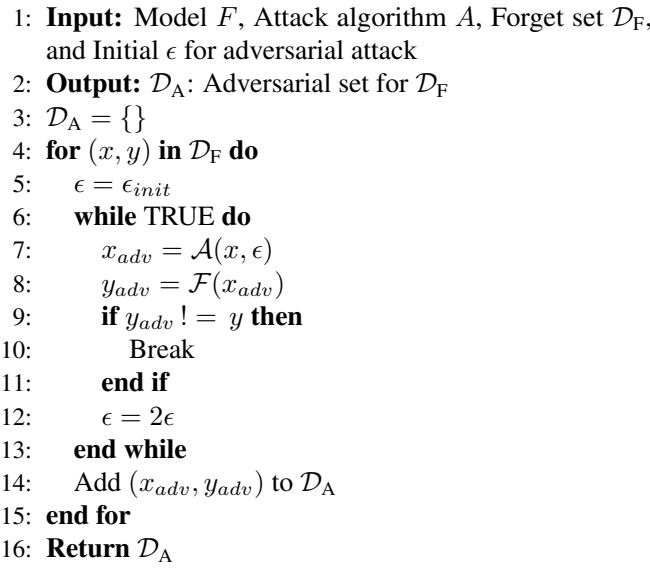

Algorithm 1: Building the Adversarial Set

The first step of AMUN is to generate these specific adversarial examples. The algorithm searches for the “closest” possible adversarial example for each image we want to forget.

How it works:

- Take a sample \((x, y)\) from the Forget Set.

- Start with a very small perturbation radius (\(\epsilon\)).

- Use an attack method (like PGD) to try and find an adversarial example within that radius.

- If the model still predicts the correct label, double the radius (\(\epsilon\)) and try again.

- Once an adversarial example \((x_{adv}, y_{adv})\) is found, add it to the dataset \(\mathcal{D}_A\).

By finding the closest possible adversarial example, the method ensures that the changes to the model are localized. We only want to affect the model’s behavior in the tiny neighborhood surrounding the data we want to delete, leaving the rest of the model’s knowledge intact.

Why “Not All Wrong is Bad”

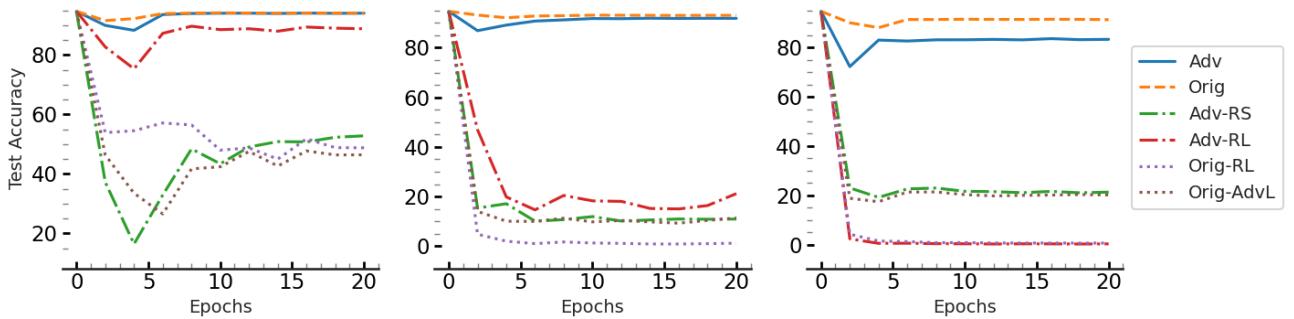

One might assume that training a model on data with wrong labels would destroy its accuracy. The authors performed an ablation study to prove this isn’t the case, provided the “wrong” data is chosen carefully.

They compared fine-tuning on:

- Adv (\(\mathcal{D}_A\)): The adversarial examples generated by AMUN.

- Random Labels: The original images with random wrong labels.

- Random Noise: Random noise images with adversarial labels.

The results in Figure 1 are striking.

- The Blue Line (Adv) represents the model fine-tuned on AMUN’s adversarial examples. Notice how the Test Accuracy (y-axis) remains stable and high.

- The Orange Dashed Line (Orig) is the baseline performance.

- The other lines (Green, Red, Purple) represent models fine-tuned on random labels or other variations of “wrong” data. They suffer from Catastrophic Forgetting—their accuracy plummets.

The Conclusion: Adversarial examples naturally belong to the distribution “learned” by the model (even if that distribution is slightly flawed). Fine-tuning on them is much safer than fine-tuning on random garbage, as it respects the model’s internal logic while correcting its over-confidence on the specific samples.

Theoretical Guarantees

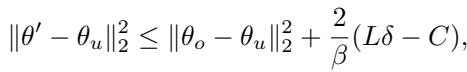

The authors back up this empirical success with a theoretical bound. They derive an upper bound on the difference between the Unlearned Model (what we get from AMUN) and the Retrained Model (the Gold Standard).

This equation might look dense, but the components tell a clear story:

- \(\delta\) (delta): This represents the distance between the original image and the adversarial example (\(||x - x_{adv}||\)).

- The Bound: The difference between our model and the perfect retrained model is proportional to \(\delta\).

Translation: The closer the adversarial example is to the original image (smaller \(\delta\)), the closer AMUN gets to the perfect “Gold Standard” of unlearning. This mathematically justifies Algorithm 1’s strategy of searching for the nearest possible adversarial example.

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested AMUN against several State-of-the-Art (SOTA) unlearning methods, including “Exact Retraining” (RETRAIN), “Fine-Tuning” (FT), and newer methods like “SalUn” and “Sparsity.”

They evaluated the methods using Membership Inference Attacks (MIA).

- The Goal: An attacker tries to guess if a specific image was in the training set.

- The Metric: We want the attack to fail. Ideally, the attack’s success rate (AUC) should be 50% (equivalent to a random coin flip). If the MIA score is high, the model hasn’t truly forgotten the data.

Setting 1: Access to Remaining Data

In the ideal scenario, the unlearning algorithm has access to the Retain Set (\(\mathcal{D}_R\))—the data that should remain in the model. This allows the method to “remind” the model of what it should keep while erasing the Forget Set.

As shown in Table 1, AMUN achieves the best performance (lowest Average Gap).

- Unlearn Acc: The accuracy on the forget set drops slightly, matching the retrained model.

- Test Acc: The accuracy on unseen data remains high (93.45%).

- MIA Gap: The membership inference attack performance is nearly identical to random guessing (FT AUC \(\approx\) 50%), proving the privacy risk is neutralized.

Setting 2: No Access to Remaining Data (The Hard Mode)

This is where AMUN truly shines. In many real-world privacy scenarios, accessing the full training dataset (\(\mathcal{D}_R\)) for every unlearning request is impossible due to storage, privacy, or regulatory silos.

Most existing methods crumble here. Without the Retain Set to anchor them, they often cause the model to forget everything (catastrophic forgetting).

However, AMUN only needs the Forget Set (\(\mathcal{D}_F\)) and the generated adversarial examples (\(\mathcal{D}_A\)). Because the adversarial examples preserve the natural distribution of the data, they inherently prevent the model from collapsing. The paper demonstrates that even without the Retain Set, AMUN outperforms competitors significantly, maintaining high test accuracy while effectively scrubbing the forget set.

Visualizing the Success

Do the confidence scores actually shift?

Figure 5 visualizes the success of AMUN.

- Left (Before Unlearning): The Forget Set (green) looks exactly like the Retain Set (blue)—high confidence.

- Right (After AMUN): The Forget Set (green) shifts left, aligning perfectly with the Test Set (orange). The model has successfully “forgotten” the distinction between the deleted data and unseen data.

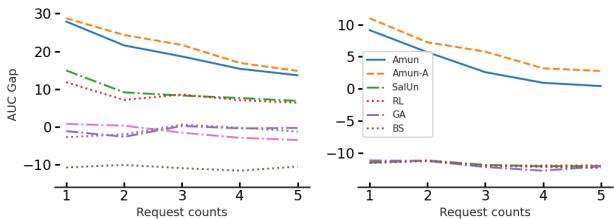

Continuous Unlearning

Real-world requests don’t happen all at once. Users delete accounts sequentially over time. A robust unlearning system must handle multiple waves of deletion requests without degrading.

Figure 2 demonstrates AMUN’s durability. Even after 5 consecutive unlearning requests (deleting 2% of the data each time), AMUN maintains a low AUC Gap. This indicates that the samples are consistently appearing more like test data than training data, even as the model undergoes repeated modifications.

Conclusion

AMUN represents a significant step forward in privacy-preserving AI. By recognizing that “not all wrong is bad,” the researchers unlocked a powerful utility for adversarial examples.

Instead of fighting against the model’s tendency to be tricked by adversarial perturbations, AMUN uses that vulnerability to perform precise “brain surgery” on the neural network. By fine-tuning on these specific, wrong-label examples, it forces the model to lower its confidence locally.

Key Takeaways:

- Efficiency: AMUN avoids the massive cost of retraining from scratch.

- Accuracy: Unlike random noise injection, using adversarial examples preserves the model’s ability to classify unseen data correctly.

- Independence: AMUN works exceptionally well even when the original training data is unavailable, solving a major logistical hurdle in data privacy compliance.

As privacy regulations tighten, techniques like AMUN will be essential for maintaining the delicate balance between powerful AI and the user’s right to delete their digital footprint.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/13000_not_all_wrong_is_bad_usi-1611/images/cover.png)