In the rapidly evolving world of Large Language Models (LLMs), we have seen AI systems graduate from solving simple textbook coding problems to winning medals in competitive programming. Yet, there remains a massive gap between solving a contained algorithm puzzle and navigating the messy, complex reality of professional software engineering.

When OpenAI announced SWE-Bench Verified, models began to show promise, but critics argued that even these benchmarks relied too heavily on isolated tasks and unit tests that could be “gamed.” The question remained: If we deployed these models in the real freelance marketplace, would they actually get paid?

Enter SWE-Lancer.

In this post, we will dissect a fascinating new paper from researchers at OpenAI that introduces a benchmark grounded not in points or accuracy percentages, but in US Dollars. By curating over 1,400 real tasks from Upwork valued at $1 million in total payouts, SWE-Lancer attempts to answer a provocative economic question: Can frontier LLMs do the job well enough to earn a paycheck?

The Problem with Current Benchmarks

To understand why SWE-Lancer is necessary, we first need to look at the limitations of existing coding evaluations.

Historically, benchmarks like HumanEval focused on program synthesis—asking a model to write a single Python function to solve a specific logic problem. While useful for early LLMs, these tasks are now trivial for models like GPT-4o.

The next evolution was SWE-Bench, which introduced repository-level context. It asked models to solve GitHub issues within popular open-source libraries. However, these benchmarks typically rely on unit tests—small, isolated code checks that verify if a specific function returns a specific value.

In the real world, software engineering is rarely about passing a unit test. It is about “End-to-End” (E2E) functionality. Does the button on the webpage actually open the modal? Does the database update correctly when a user submits a form? Does the fix work across mobile and web platforms? Furthermore, real engineering involves management decisions: choosing between different architectural proposals based on trade-offs, dependencies, and technical debt.

Current benchmarks largely ignore these “full-stack” and “managerial” complexities. SWE-Lancer aims to fill this void.

Introducing SWE-Lancer

SWE-Lancer is constructed from 1,488 real freelance tasks sourced from the open-source repository of Expensify, a publicly traded company. These tasks were originally posted on Upwork, meaning real human freelancers were paid real money to solve them.

The benchmark distinguishes itself through two major innovations:

- Economic Grounding: Every task has a specific dollar value attached to it, ranging from \(50 bug fixes to \)32,000 feature implementations.

- Role Division: The benchmark splits tasks into two distinct categories: Individual Contributor (IC) tasks and Software Engineering (SWE) Manager tasks.

1. The Individual Contributor (IC) Tasks

The IC component of the benchmark simulates the daily work of a developer. The model is presented with a codebase, an issue description, and a request to fix a bug or implement a feature.

Unlike previous benchmarks that check code using unit tests (which can often be brittle or susceptible to “overfitting”), SWE-Lancer uses End-to-End (E2E) tests. These tests were created and triple-verified by professional software engineers. They use browser automation (via Playwright) to actually interact with the application—clicking buttons, typing into fields, and verifying visual and logical outcomes.

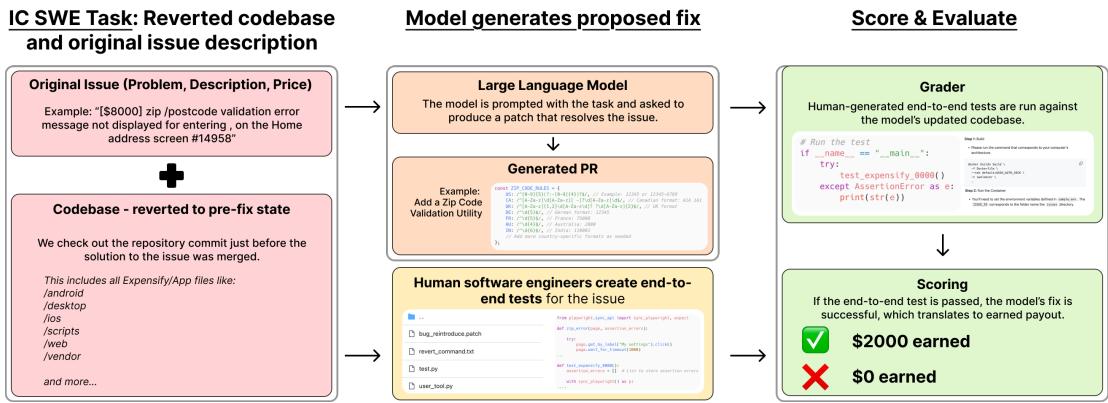

As shown in Figure 1, the workflow is rigorous:

- Input: The model receives the issue description (e.g., “Validation error not displayed”) and the pre-fix codebase.

- Action: The model generates a patch (a “Pull Request”).

- Evaluation: The system runs human-generated E2E tests against the patched code.

- Payout: If—and only if—the tests pass, the model “earns” the associated payout (e.g., \(2,000). If the tests fail, it earns \)0.

This approach prevents models from writing code that looks correct syntactically but fails to render properly in a browser or breaks a user flow.

2. The SWE Manager Tasks

Software engineering isn’t just about writing code; it is also about deciding what code to write. In the Expensify/Upwork workflow, freelancers submit proposals for how they intend to fix an issue. A manager then reviews these proposals and selects the best one.

SWE-Lancer captures this dynamic by asking the LLM to act as the manager.

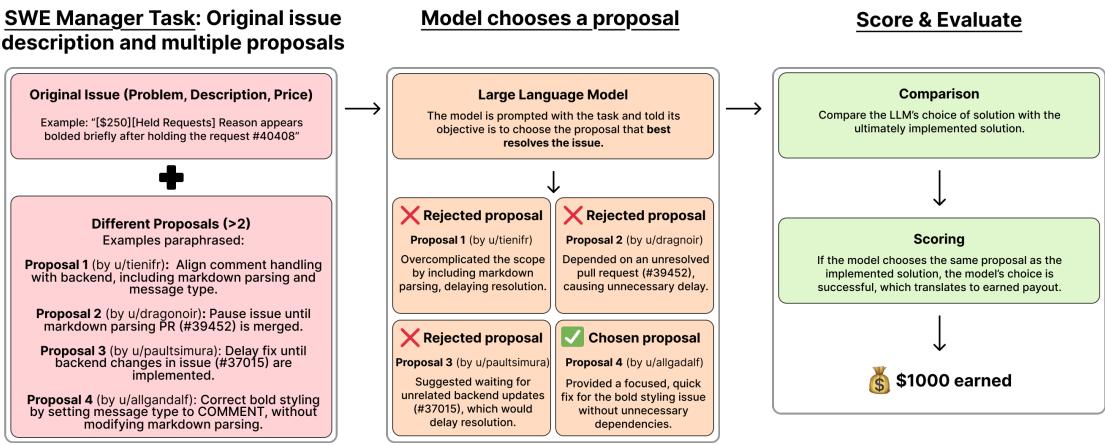

Figure 2 illustrates this decision-making process:

- Context: The model is given the issue description, the price, and a set of real proposals submitted by humans (e.g., “Proposal 1 by u/tienifr,” “Proposal 2 by u/dragonir”).

- Reasoning: The model can browse the codebase to verify the technical claims made in the proposals. It must identify which proposal is technically sound, minimizes technical debt, and actually solves the root cause.

- Selection: The model chooses a winner.

- Grading: The model’s choice is compared against the actual decision made by the human engineering manager who ran the project. If the model picks the same winner, it earns the payout.

This is a crucial addition to the field, as it tests an LLM’s ability to “reason” about code architecture and trade-offs rather than just generating syntax.

3. Dynamic Pricing and Difficulty

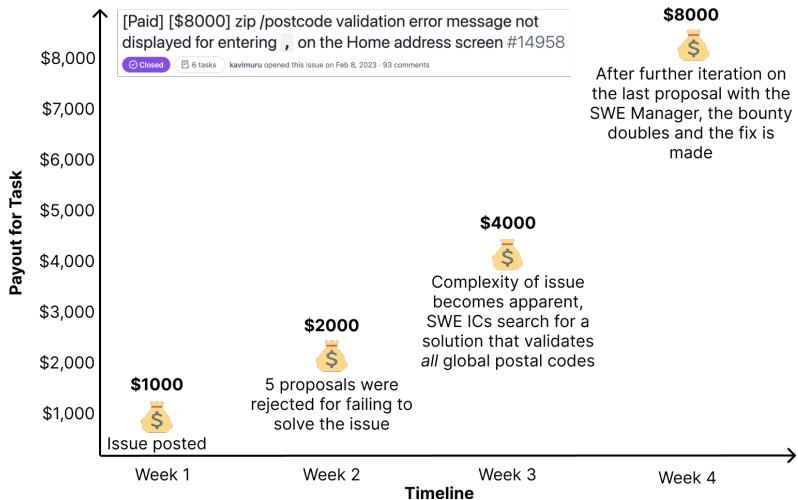

One of the most interesting aspects of SWE-Lancer is that the difficulty is market-derived. In standard benchmarks, tasks are often treated as equal units. In SWE-Lancer, a \(50 task is generally simpler than an \)8,000 task.

Figure 4 demonstrates how this pricing works in practice. A task regarding a zip code validation error started with a \(1,000 bounty. However, as freelancers submitted proposals that failed to account for edge cases (like global postal codes), the complexity became apparent. The bounty was raised repeatedly over four weeks, eventually settling at \)8,000.

This dynamic pricing creates a natural difficulty gradient. By evaluating models based on earnings, we give more weight to the complex, high-value problems that actually drive economic impact, rather than simple typos or one-line fixes.

Comparing SWE-Lancer to the Status Quo

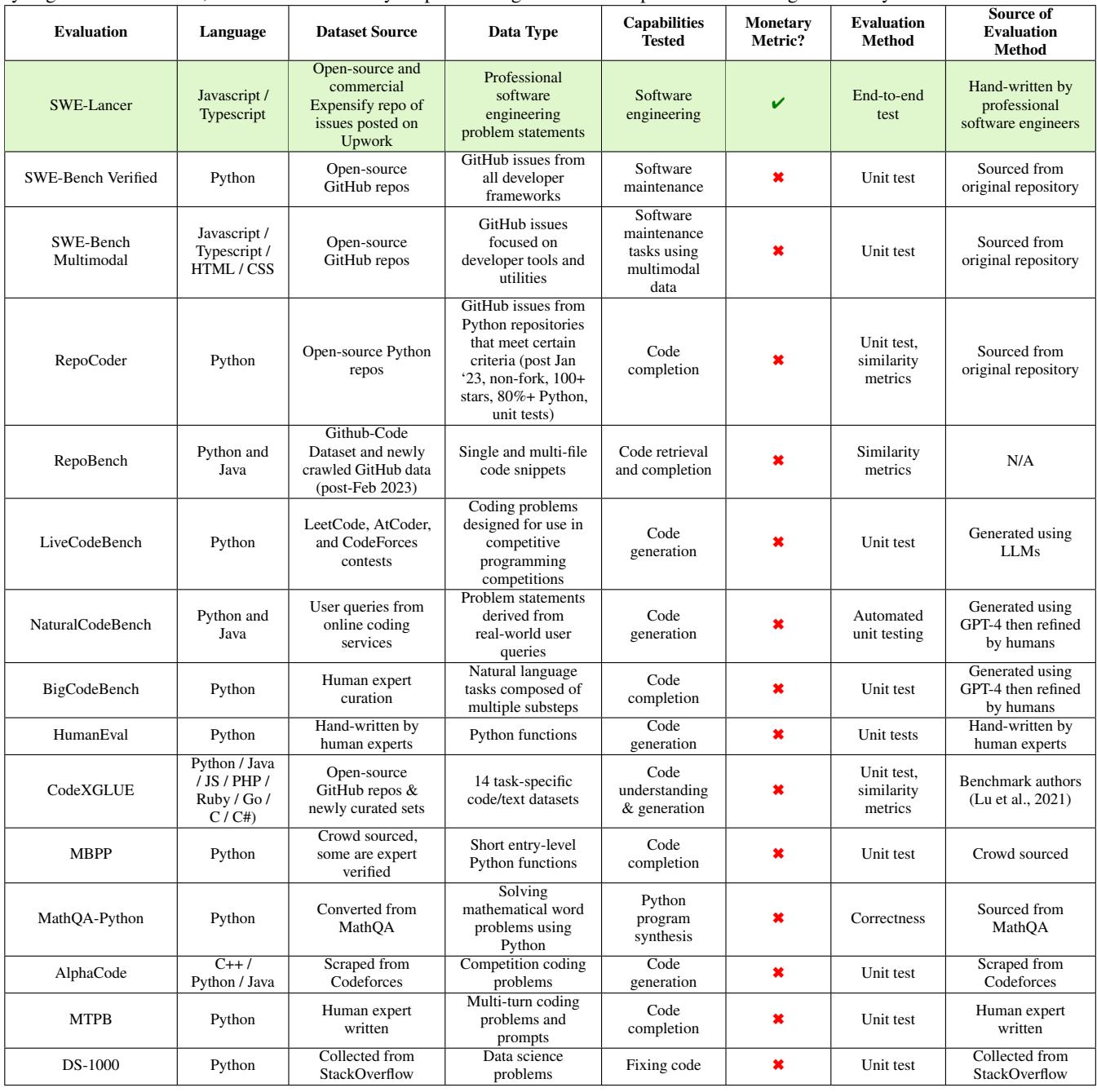

To truly appreciate the leap SWE-Lancer represents, it helps to compare it directly with existing benchmarks.

As detailed in Table 5, most benchmarks (like SWE-Bench Verified or RepoBench) rely on unit tests sourced from the repository. SWE-Lancer is unique in using End-to-End tests handcrafted by engineers and mapping performance to monetary metrics. It also stands out as the only major benchmark to include a dedicated “Management” evaluation track.

Experimental Setup

The researchers evaluated three frontier models:

- GPT-4o (OpenAI)

- o1 (OpenAI, formerly known as Strawberry/Q*, using high reasoning effort)

- Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic)

To ensure fairness and realism:

- Environment: Agents ran in a secure Docker container with no internet access (preventing them from looking up the solution online).

- Tools: Models were given a basic scaffold allowing them to browse the codebase, search files, and run terminal commands. Crucially, they were given a “User Tool”—a simulator that runs the app in a browser so the model can verify its own fixes before submitting.

- Data Split: The researchers released a public “Diamond” set ($500k value) but kept a private holdout set to prevent future models from training on the test data.

Results: Show Me the Money

So, how much money can today’s AI actually earn?

The short answer is: A significant amount, but nowhere near the full $1 million potential.

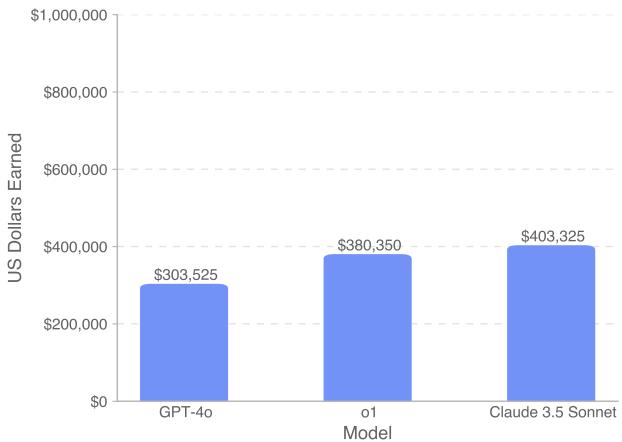

Figure 5 shows the total earnings across the full dataset. Claude 3.5 Sonnet emerged as the top earner, securing over \(400,000. OpenAI’s reasoning model, o1, followed closely with approximately \)380,000, while GPT-4o trailed at around $300,000.

While earning \(400k sounds impressive, remember that the total available pot was \)1,000,000. This means even the best model left nearly 60% of the money on the table, indicating that AI is not yet ready to fully automate freelance software engineering.

Breakdown: Coding vs. Managing

The aggregate numbers hide a significant disparity between the models’ ability to write code versus their ability to manage it.

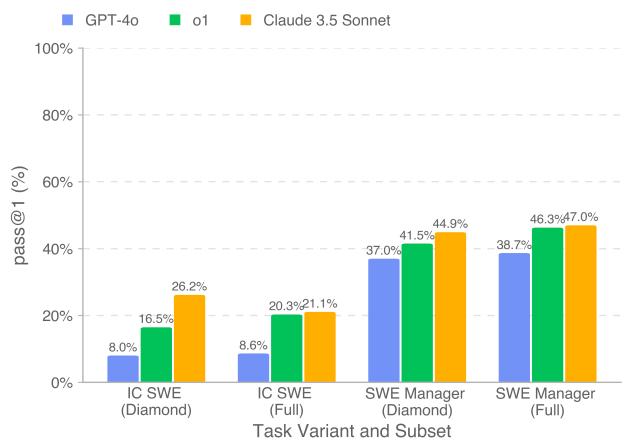

Figure 6 provides a granular look at the success rates (Pass@1):

- IC SWE Tasks (Coding): This remains very difficult for models. The best model, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, only solved 26.2% of the tasks in the Diamond set. GPT-4o struggled significantly, solving only 8%.

- SWE Manager Tasks (Decision Making): Models performed much better here. Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieved nearly 45% accuracy, and o1 was close behind.

This suggests that current frontier models are surprisingly good at evaluating technical proposals—perhaps better than they are at implementing the details themselves. They can identify the right path but trip up when trying to walk it.

The Value of “Reasoning” and Multiple Attempts

The researchers also investigated what factors allow models to earn more. Two key levers were identified: Attempts and Reasoning Effort.

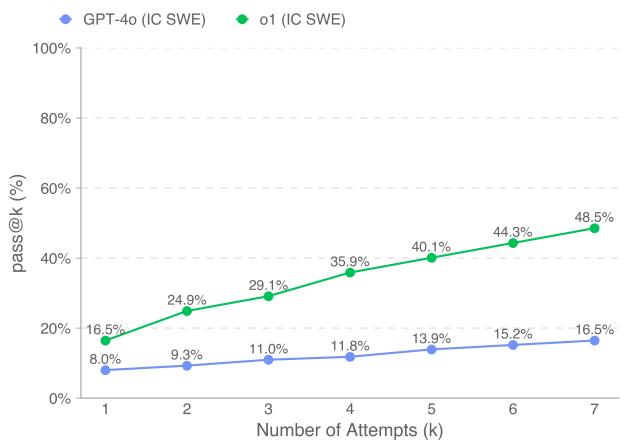

Figure 7 (labeled Figure 6 in the image deck due to numbering) illustrates the impact of giving the model multiple tries (pass@k).

- o1 (Green Line): Starts at 16.5% success on the first try but skyrockets to 48.5% if allowed 7 attempts.

- GPT-4o (Blue Line): Sees a much flatter improvement curve.

This highlights the value of the “reasoning” capabilities in models like o1. When o1 fails, it likely fails for different, addressable reasons that a retrial can fix. GPT-4o often gets stuck in the same failure modes.

Similarly, increasing the test-time compute (how long the model “thinks” before answering) showed a clear correlation with earnings, particularly for the more expensive, complex tasks.

The Economic Argument: AI as a Cost-Saver

Perhaps the most practical takeaway for the industry is not whether AI can replace engineers, but whether it can make them cheaper.

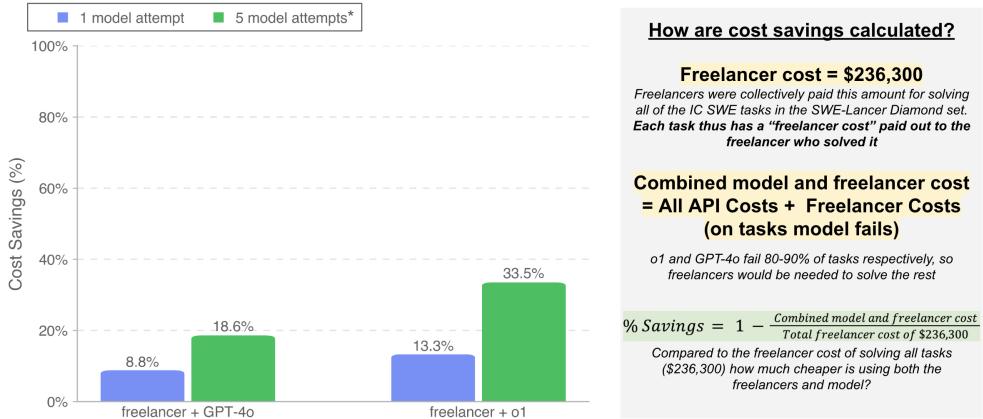

The researchers modeled a hybrid workflow: What if we let the AI try to solve the task first, and only hand it off to a human freelancer if the AI fails?

Figure 10 presents this cost-benefit analysis.

- Scenario: The model attempts the task. If it succeeds, the cost is just the API fees (pennies or dollars). If it fails, you pay the full freelancer price.

- Result: By allowing the o1 model 5 attempts before falling back to a human, a company could reduce total costs on the Diamond dataset by 33.5%.

This is a massive potential efficiency gain. Even with a success rate under 30%, the low cost of AI inference compared to human labor means that automated attempts are economically viable “lottery tickets.”

Challenges and Future Work

Despite the promising numbers, the paper highlights significant limitations:

- Root Cause Analysis: Models are great at finding where the bug is (localization) but often fail to understand why it is happening across multiple files. They tend to apply “band-aid” fixes rather than systemic solutions.

- Tool Use: While strong models use the provided User Tool (browser simulator) to debug, weaker models often give up on it or fail to parse the output effectively.

- Contamination Risks: Since these tasks are from public GitHub repositories, there is always a risk that models have seen this code during training. The researchers mitigate this with the private holdout set, but it remains a challenge in the field.

Conclusion

SWE-Lancer represents a maturity milestone for AI evaluation. By moving away from abstract points and towards real-world dollars, it provides a clearer picture of where we stand.

The verdict? AI is not ready to be a Senior Software Engineer. Solving only ~26% of coding tasks demonstrates that human expertise is still vital for execution. However, the models’ strong performance in “Manager” tasks and the potential for 33% cost savings in hybrid workflows suggest that AI is ready to be a highly effective junior engineer or technical assistant.

As models like Claude 3.5 Sonnet and OpenAI’s o1 continue to improve their reasoning and tool-use capabilities, we can expect that percentage of “money left on the table” to shrink. For now, the freelance market is safe—but the tools to navigate it are getting sharper every day.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/13597_swe_lancer_can_frontier_-1885/images/cover.png)