Introduction

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) has undeniably changed the landscape of Artificial Intelligence. It is the engine under the hood of modern Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Llama 2, allowing them to align with human intent. The standard recipe for RLHF usually involves training a reward model to mimic human preferences and then optimizing a policy to maximize that reward.

However, a new wave of research, spearheaded by methods like Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), has simplified this process. DPO skips the explicit reward modeling step entirely, optimizing the policy directly from preference data. It’s elegant, stable, and effective—at least when the data behaves nicely.

But what happens when we move out of the text-generation comfort zone and into the messy world of robotics or complex control systems? In these domains, the environment is stochastic (random), and the data often comes from a mix of skilled and unskilled operators.

Here lies a hidden trap in current methods: Likelihood Mismatch. Standard DPO-style algorithms often implicitly assume that the trajectories in the dataset were generated by an optimal (or near-optimal) policy. When a bad policy gets “lucky” due to environmental noise, existing methods might misinterpret this as skill, leading to suboptimal learning.

In this post, we will dive deep into a paper titled “Policy-labeled Preference Learning: Is Preference Enough for RLHF?”. The researchers propose a novel framework called Policy-labeled Preference Learning (PPL). PPL argues that preference labels alone are not enough; to truly learn from offline data, we must also account for who generated that data—the behavior policy.

Background: The Shift to Direct Preferences

To understand PPL, we first need to look at where we are coming from.

Traditional RLHF vs. DPO

In traditional RLHF (like PEBBLE), the process is two-staged:

- Reward Learning: Collect pairs of trajectories \((\zeta^+, \zeta^-)\) where humans prefer \(\zeta^+\). Train a neural network to predict a scalar reward \(r(s,a)\) that explains these preferences.

- Policy Optimization: Use a standard RL algorithm (like PPO or SAC) to maximize this learned reward.

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and its variants (like CPL) realized that for every reward function, there is a corresponding optimal policy. By using this mathematical duality, they formulated a loss function that optimizes the policy directly from preferences, removing the need for a separate reward model.

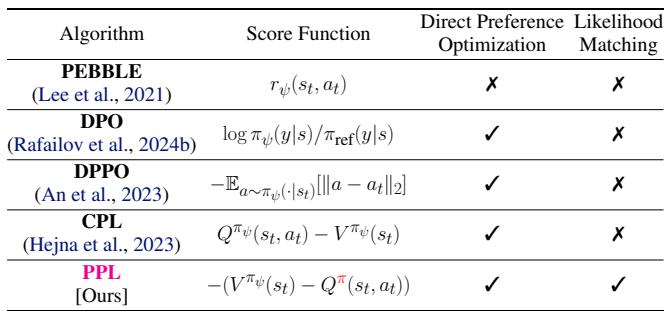

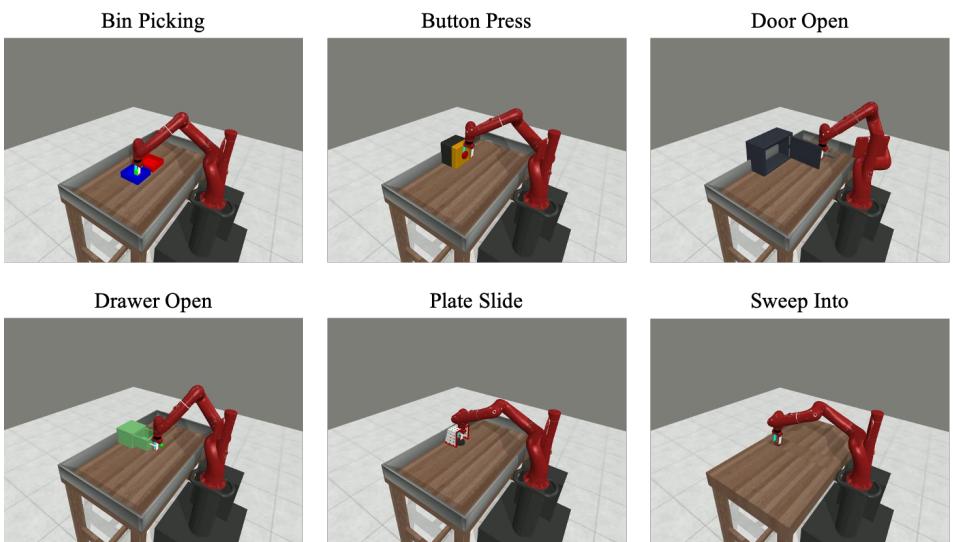

Table 1 below summarizes how different algorithms approach this problem. Notice that PPL is unique in that it incorporates Likelihood Matching, a concept we will explore shortly.

The Problem with “Returns”

In Reinforcement Learning, we usually care about the cumulative return (sum of rewards). However, in sparse-reward environments (like a robot trying to pick up an object), the return is often uninformative for long stretches of time.

The authors argue that Regret is a much better metric than raw reward for learning from preferences. Regret measures the difference between the value of the optimal action and the value of the action actually taken.

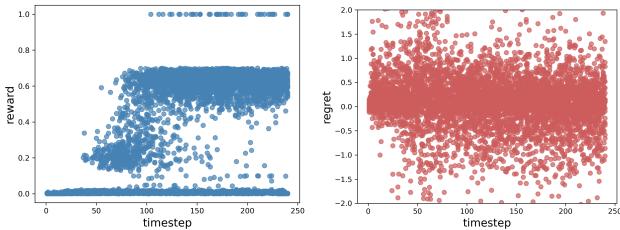

As visualized in Figure 1 below, rewards (left) can be incredibly sparse—you get nothing until you succeed. Regret (right), however, provides a dense signal at every timestep, telling you exactly how suboptimal a specific move was.

While Contrastive Preference Learning (CPL) attempted to use optimal advantage (a relative of regret), it missed a crucial piece of the puzzle: the behavior policy.

The Core Problem: Likelihood Mismatch

The central thesis of this paper is that ignoring the source of the data leads to learning errors.

In many offline RL datasets, the data is heterogeneous. It comes from diverse sources: a random explorer, a scripted bot, a novice human, and an expert human.

- Environmental Stochasticity: Sometimes, a bad policy makes a bad move, but the environment randomly transitions to a good state.

- Policy Suboptimality: Sometimes, a good policy makes a good move, but the environment transitions to a bad state.

If your algorithm assumes all data comes from an “optimal” distribution (as DPO-style methods often implicitly do), it cannot distinguish between “getting lucky” and “being good.”

Visualizing the Mismatch

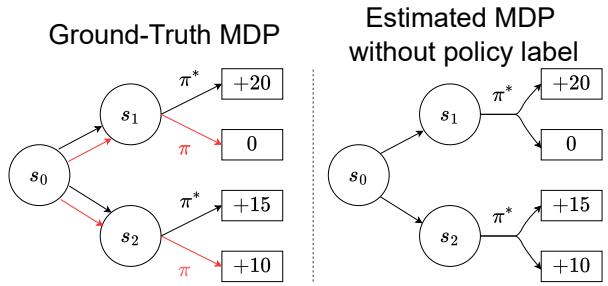

Consider the diagram in Figure 3.

On the left (Ground-Truth MDP), we see the reality:

- Policy \(\pi^*\) (optimal) takes an action that leads to \(s_1\) with a high reward (+20).

- Policy \(\pi\) (suboptimal) takes an action that leads to \(s_2\) with a lower reward (+10).

Clearly, \(s_1\) is preferred.

However, look at the right side (Estimated MDP without policy label). If we don’t know which policy generated which path, and we just look at the outcomes, the learning algorithm might get confused by the transition probabilities. If the dataset contains many trajectories where the suboptimal policy \(\pi\) accidentally reached a good state, or the optimal policy \(\pi^*\) got unlucky, the algorithm might incorrectly infer that the action leading to \(s_2\) is actually the better choice.

This is Likelihood Mismatch. The algorithm attributes the outcome to the dynamics of the world rather than the quality of the policy that acted.

The Solution: Policy-labeled Preference Learning (PPL)

The researchers propose PPL to fix this. The core idea is simple but profound: Label the trajectory with the policy that generated it.

By explicitly modeling the behavior policy (\(\pi\)), PPL can mathematically disentangle the environmental noise from the policy’s skill.

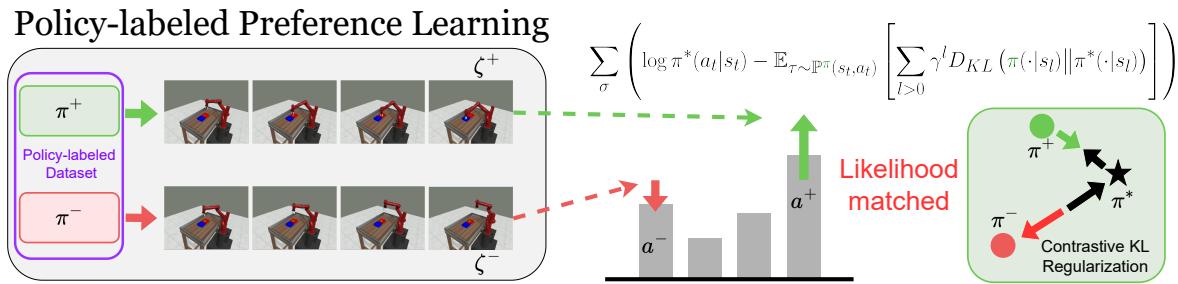

As shown in Figure 2, PPL uses a contrastive learning framework. It doesn’t just ask “which path is better?”; it asks “given that Policy A produced Path A and Policy B produced Path B, which policy deviation explains the preference?”

Theoretical Foundation: Defining Regret

The authors ground their method in the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) framework. In MaxEnt RL, the optimal policy maximizes not just reward, but also the entropy (randomness) of the policy, which encourages exploration and robustness.

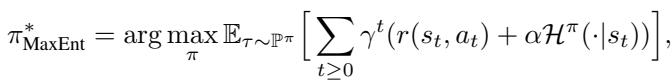

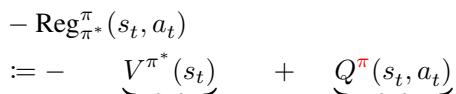

The optimal policy \(\pi^*\) in this framework is defined as:

The paper introduces a rigorous definition of Negative Regret. Regret is essentially the difference between the value (\(V\)) you would expect under the optimal policy versus the Q-value (\(Q\)) of the action you actually took.

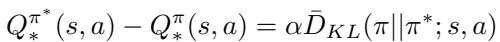

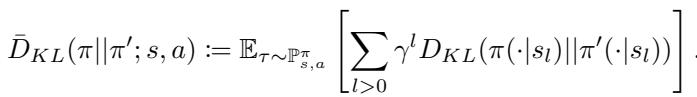

Here is the crucial theoretical contribution. The authors derive the Policy Deviation Theorem (Theorem 3.4). They prove that this difference (regret) relates directly to the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the behavior policy and the optimal policy.

Where \(\bar{D}_{KL}\) is the sequential forward KL divergence:

What does this mean in plain English? It means that “Regret” isn’t just a vague concept of “missing out.” It is mathematically equivalent to the distance (KL divergence) between your policy and the optimal policy over time. If you minimize regret, you are minimizing the distance to the optimal policy.

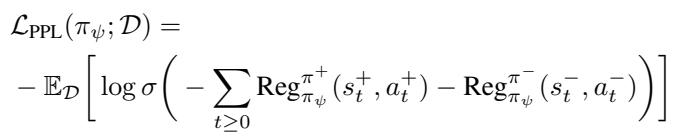

The PPL Objective Function

Using this theorem, the authors decompose the regret into two parts:

- Likelihood: How probable was this action under the optimal policy?

- Sequential KL: How much does the trajectory diverge from the optimal path in the future?

This leads to the PPL Loss function. Instead of just pushing up the probability of the preferred trajectory, PPL optimizes this objective:

Specifically, looking at the score function inside the loss, we see it balances immediate action likelihoods with future divergence:

This equation tells the model to:

- Increase the likelihood of actions in the preferred segment (\(\zeta^+\)).

- Decrease the likelihood of actions in the dispreferred segment (\(\zeta^-\)).

- Crucially: Minimize the future divergence (KL) for the winner and maximize it for the loser.

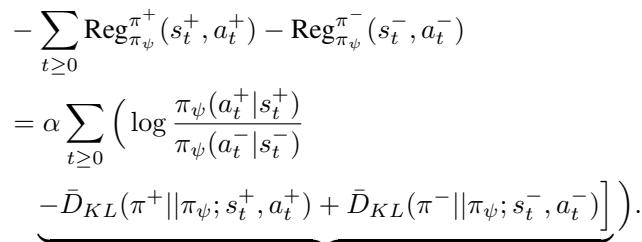

Contrastive KL Regularization

The term involving \(\bar{D}_{KL}\) is what the authors call Contrastive KL Regularization.

In standard DPO, you usually only look at the specific state-action pairs in the dataset. PPL goes a step further by “rolling out” (simulating) a few steps into the future (or using the recorded future steps) to see where the policy leads.

The practical implementation approximates this infinite sum with a look-ahead horizon \(L\):

This regularization ensures that the learned policy aligns with the preferred trajectory sequentially, not just instantaneously. It forces the model to understand the long-term consequences of an action, thereby solving the likelihood mismatch issue.

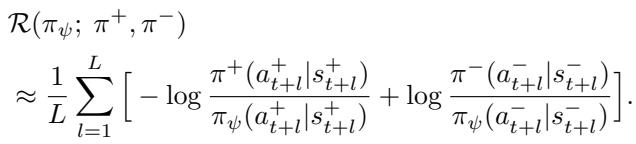

Experiments and Results

The authors tested PPL on the MetaWorld benchmark, a standard testbed for robotic manipulation tasks.

They focused on offline learning, where the agent must learn from a fixed dataset without interacting with the world. They created two types of datasets:

- Homogeneous: Data collected mostly from one type of policy.

- Heterogeneous: A messy mix of policies (e.g., some with 20% success rate, some with 50%).

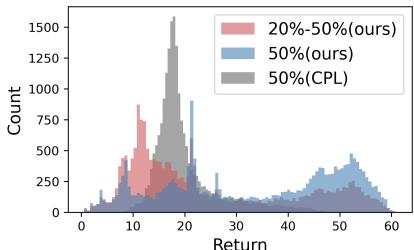

The heterogeneous dataset is particularly challenging because it mimics real-world scenarios where data is messy. Figure 4 shows the distribution of returns in these datasets. Notice how the heterogeneous data (Red) has a weird, multi-modal distribution compared to the standard datasets used in previous works (Gray).

Main Results

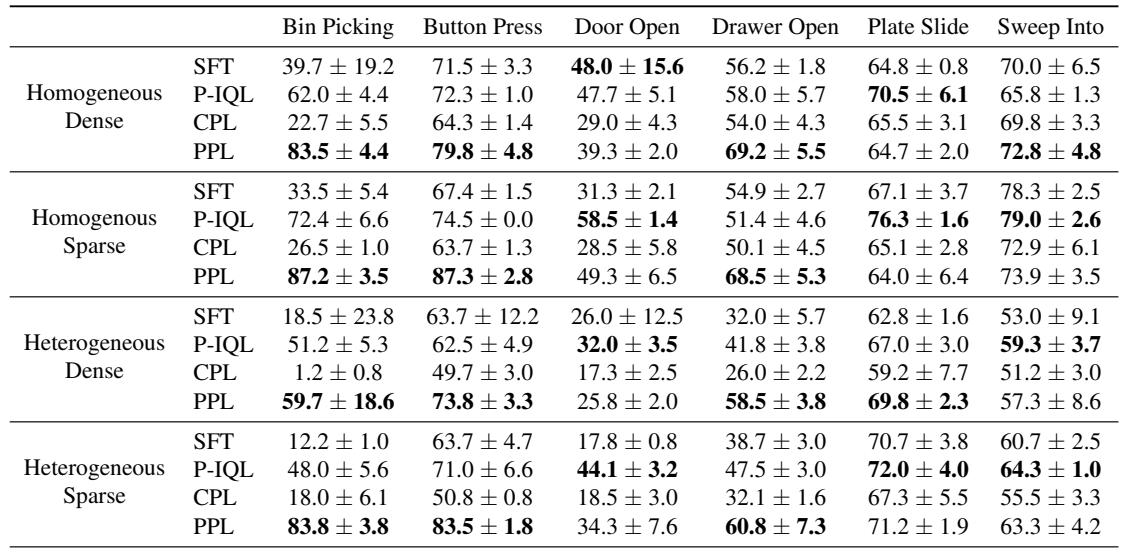

The results, summarized in Table 2, are quite striking. PPL consistently outperforms the baselines, especially Contrastive Preference Learning (CPL) and Preference-based IQL (P-IQL).

Key Takeaways from the Results:

- Dominance in Sparse/Heterogeneous Settings: Look at the “Heterogeneous” rows. In tasks like Bin Picking and Door Open, standard CPL fails almost completely (1.2% and 17.3% success). PPL maintains high performance (59.7% and 25.8%).

- Efficiency: P-IQL (a reward-based method) performs decently but requires training a separate reward model and critic, using nearly 10x the parameters of PPL. PPL achieves similar or better results with a fraction of the computational cost.

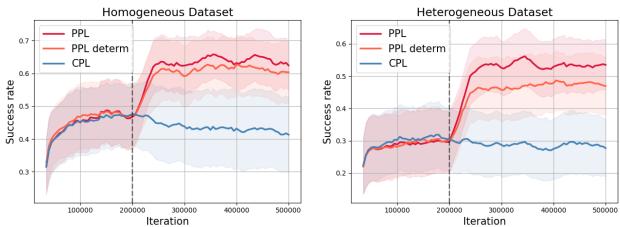

Does the Label Really Matter?

You might wonder: “Is it the math, or is it just the fact that you told the model which policy was acting?”

To answer this, the authors ran an ablation study comparing PPL against PPL-deterministic. In the deterministic version, they assume a generic policy rather than using the true behavior policy labels.

As shown in Figure 5, knowing the policy (Red line) provides a clear advantage over guessing it (Orange line), particularly in complex tasks like Bin Picking. This empirically proves that the “Likelihood Mismatch” is a real problem and that explicit policy labeling is the solution.

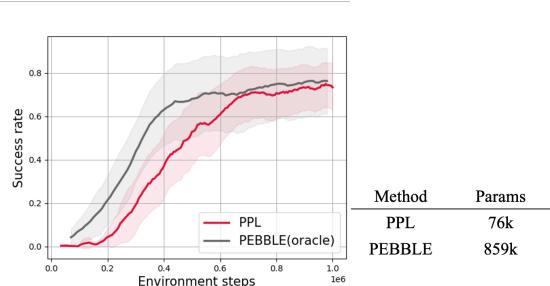

Online Learning

Finally, the authors asked if PPL works in an Online setting, where the agent interacts with the environment and generates new data on the fly.

Figure 6 shows that PPL (Red) matches the performance of PEBBLE (Gray), a strong baseline that uses unsupervised pre-training. PPL achieves this from scratch, further highlighting its data efficiency.

Conclusion & Implications

The paper “Policy-labeled Preference Learning” highlights a subtle but critical flaw in how we approach RLHF: the assumption that preference implies optimality. By ignoring the source of the data, we risk confusing environmental luck with agent skill.

PPL offers a robust solution by:

- Using Regret: A denser, more informative signal than sparse rewards.

- Policy Labeling: Explicitly accounting for the behavior policy to fix likelihood mismatch.

- Contrastive KL Regularization: Ensuring the learned policy aligns with preferred trajectories over the long term.

For students and researchers in RL, this work underscores the importance of the data generation process. In the era of big data, it’s easy to treat datasets as static collections of state-action pairs. PPL reminds us that every data point tells a story of a specific policy interacting with a specific environment, and understanding that story is key to learning optimal behavior.

As we move toward deploying robots in the real world, dealing with messy, heterogeneous human data will be unavoidable. Frameworks like PPL pave the way for agents that can sift through this noise and learn not just what we prefer, but how to achieve it reliably.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/14278_policy_labeled_preferenc-1750/images/cover.png)