Introduction

In the era of Large Language Models (LLMs), we have become accustomed to witnessing AI perform seemingly miraculous feats. From passing the Bar exam to writing complex Python scripts, models like GPT-4 appear to possess a deep understanding of the world. But there is a persistent, nagging question in the Artificial Intelligence community: Are these models actually reasoning, or are they just sophisticated pattern matchers?

When an LLM answers a question, is it following a logical chain of thought—deriving conclusion \(C\) from premises \(A\) and \(B\)—or is it simply retrieving the most statistically probable sequence of words?

This distinction is critical. For AI to be trusted in high-stakes fields like law, medicine, or engineering, it must be capable of rigorous First-Order Logic (FOL) reasoning. It cannot just “feel” that an answer is right; it must be able to prove it deductively.

Enter FOLIO, a groundbreaking research paper and dataset that aims to put this specific capability to the test. Unlike previous benchmarks that tested “fuzzy” reasoning or relied on simple synthetic data, FOLIO introduces a logically rigorous, expert-annotated dataset designed to expose the cracks in modern LLMs’ reasoning capabilities.

In this post, we will tear down the FOLIO paper, explore how the dataset was constructed, and analyze why even the world’s most powerful models struggle to solve its puzzles.

The Problem with Existing Benchmarks

To understand why FOLIO is necessary, we first need to look at the landscape of AI evaluation. There are plenty of datasets designed to test “reasoning,” but they generally fall into two traps:

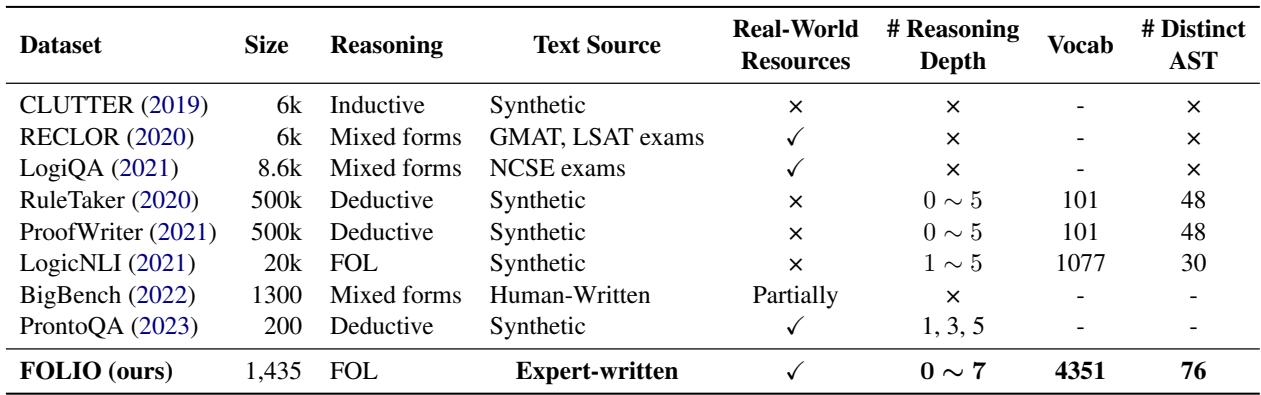

- Lack of Naturalness: Datasets like RuleTaker or ProofWriter focus on deductive logic, but they are generated synthetically. They use a tiny vocabulary (sometimes as few as 100 words) and repetitive sentence structures. They look like math problems dressed up as text, which makes them easy for models to “game” without understanding real language.

- Lack of Logical Purity: Datasets like ReClor or LogiQA are taken from exams like the LSAT. While the language is natural, the reasoning is often “inductive” or relies on outside commonsense knowledge. This makes it hard to isolate the model’s ability to perform pure logical deduction.

The authors of FOLIO highlight these deficiencies clearly. They wanted to create a dataset that was both linguistically diverse (using real, complex English) and logically rigorous (adhering to strict First-Order Logic).

As shown in Table 1, FOLIO stands out as the first expert-written dataset that combines First-Order Logic (FOL) with a large vocabulary (4,351 words) and deep reasoning chains (up to 7 steps). Unlike its predecessors, which often rely on simple “If A then B” chains, FOLIO introduces complex logical structures involving universal quantifiers (“All”), existential quantifiers (“Some”), negations, and disjunctions (“Or”).

The FOLIO Method: Bridging Language and Logic

The core contribution of this paper is the creation of the FOLIO corpus itself. The goal was to create a set of problems where a model is given a “story” (a set of premises) and must determine if a conclusion is True, False, or Unknown.

To ensure the ground truth was indisputable, the researchers didn’t just ask humans to label the data. They implemented a parallel annotation system where every natural language sentence is paired with a formal First-Order Logic formula.

The Structure of an Example

Let’s look at a concrete example from the dataset to understand what the models are up against.

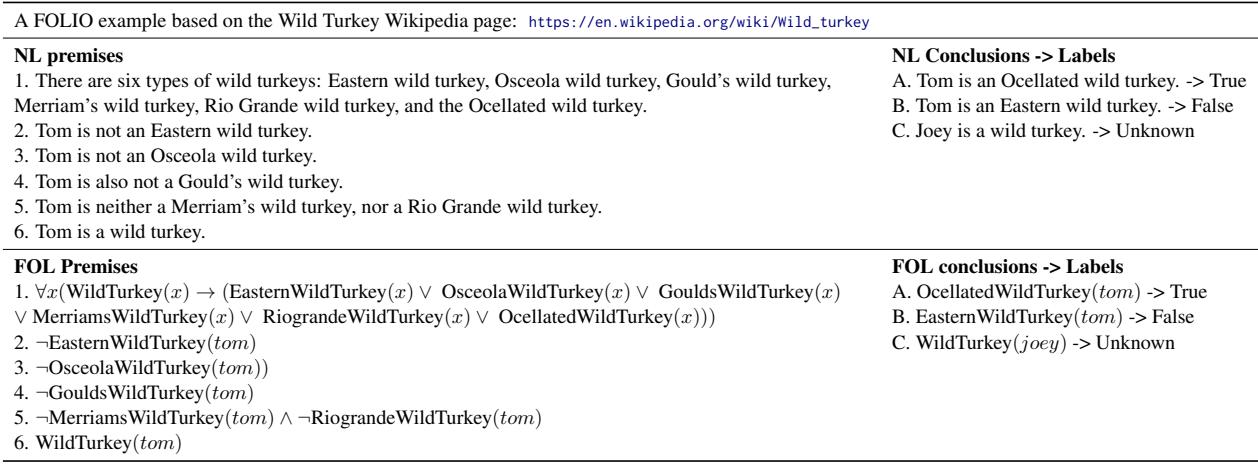

In Table 2, we see a story about wild turkeys.

- The Premises: The text defines the world. There are six specific types of wild turkeys. We are told about a turkey named Tom. We are explicitly told what Tom is not (he is not Eastern, Osceola, Gould’s, etc.).

- The Logic: This is a classic process of elimination (Disjunctive Syllogism). If \(x\) must be one of \(\{A, B, C, D, E, F\}\), and we know \(\neg A, \neg B, \neg C, \neg D, \neg E\), then logically, \(x\) must be \(F\).

- The Conclusion: “Tom is an Ocellated wild turkey.”

- The Label: True.

Crucially, notice the FOL Premises column. The researchers mapped the English sentence “Tom is not an Eastern wild turkey” to the logical formula \(\neg EasternWildTurkey(tom)\). This dual structure allows the dataset to be verified mathematically. If the logic engine says the conclusion follows from the premises, the label is mathematically guaranteed to be correct.

Building the Dataset: WikiLogic and HybLogic

Creating this dataset was not a matter of scraping the web. It required highly skilled labor—specifically, computer science students with formal training in logic. The team spent nearly 1,000 man-hours creating the data using two distinct strategies:

- WikiLogic: Annotators took random Wikipedia articles and wrote logical stories based on real-world facts. This ensures the language is natural and covers diverse topics.

- HybLogic (Hybrid): This approach started with complex logical templates (e.g., specific syllogisms) and then “filled in the blanks” with natural language concepts. This method was used to forcefully inject highly complex reasoning patterns that might not appear frequently in random Wikipedia articles.

The Complexity of Depth

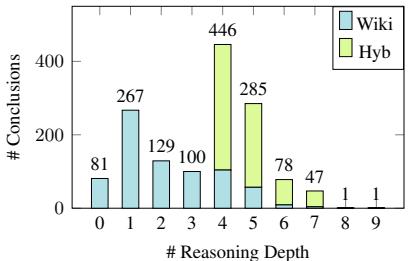

One of the defining features of FOLIO is the reasoning depth. This refers to the number of logical steps required to bridge the gap from the premises to the conclusion.

Most previous datasets topped out at a depth of 5. FOLIO pushes this further.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of these depths. While the WikiLogic examples (blue) tend to be shorter (1-5 steps), the HybLogic examples (green) introduce deep, tortuous reasoning chains reaching up to 7 or 8 steps. This “long-tail” of complexity is exactly where Large Language Models tend to break down.

The Experiments

The researchers proposed two primary tasks to evaluate modern AI:

- Logical Reasoning: Can the model predict the correct label (True/False/Unknown) given the natural language premises?

- NL-FOL Translation: Can the model translate the English text into valid First-Order Logic code?

They tested a variety of models, ranging from fine-tuned “small” models like BERT and RoBERTa to massive Logic-LM systems and, of course, GPT-3.5 and GPT-4.

Task 1: Logical Reasoning Results

The results were sobering. In a world where we expect AI to be superhuman, FOLIO exposes a significant gap.

Table 4 presents the main leaderboard. Here are the key takeaways:

- Fine-tuning works well for small contexts: Surprisingly, a fine-tuned Flan-T5-Large (a much smaller model than GPT-4) achieved 65.9% accuracy. This suggests that if you train a model specifically on this type of logic, it can learn the patterns.

- GPT-4 is not a perfect reasoner: Out of the box (standard prompting), GPT-4 scored 61.3%. Even with advanced prompting techniques like “Chain of Thought” (CoT), it peaked around 68-70%.

- The Gap: Specialized neuro-symbolic methods (like Logic-LM) that combine LLMs with external code solvers pushed the score to 78.1%. However, simply asking an LLM to “think” its way through the problem is still prone to error.

The Impact of Reasoning Depth

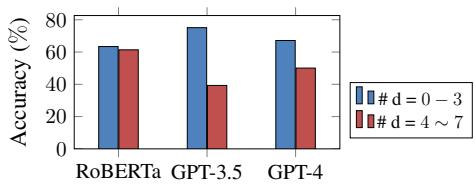

Why is GPT-4 scoring only 60-70%? The answer lies in the complexity of the chains. The researchers broke down the model performance by reasoning depth.

Figure 2 shows a clear trend. When the reasoning is shallow (\(d=0-3\)), GPT-4 performs respectably (over 75%). But when the problem requires holding 4 to 7 logical steps in context simultaneously, performance plummets to near 50%—barely better than a coin flip. This confirms that while LLMs capture surface-level logic, they struggle to maintain coherence over long deductive chains.

Task 2: NL-FOL Translation

The second task asked models to act as translators: convert English premises into FOL formulas. If models could do this perfectly, we could just feed the formulas into a logic solver and get 100% accuracy.

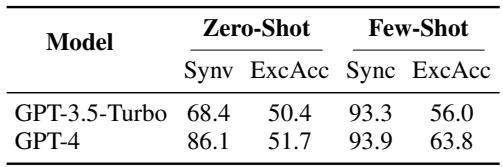

Table 5 reveals a fascinating dichotomy:

- Syntactic Validity (SynV): GPT-4 is excellent at writing code that looks correct. It achieved 93.9% syntactic validity. The formulas had the right brackets, symbols, and syntax.

- Execution Accuracy (ExcAcc): However, the code was often semantically wrong. When the generated formulas were run through a logic engine, they produced the correct answer only 63.8% of the time.

This implies that the model understands the grammar of logic but often fails to capture the precise meaning of the English sentence it is translating.

Error Analysis: Where do LLMs Go Wrong?

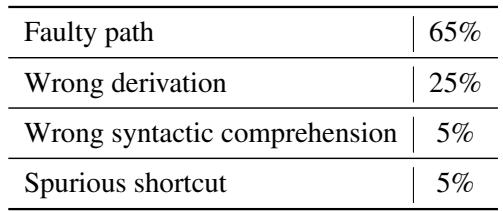

To understand how the models failed, the authors conducted a human evaluation of GPT-4’s incorrect answers. They categorized the errors into four types.

As shown in Table 7, the vast majority of errors (65%) were classified as “Faulty Path.” This means the model started reasoning correctly but took a wrong turn somewhere in the middle of the chain. It didn’t fail because it didn’t understand the words (Syntactic comprehension errors were only 5%); it failed because it couldn’t sustain the deduction.

The “True” Bias

Another interesting finding was a bias in the models’ predictions.

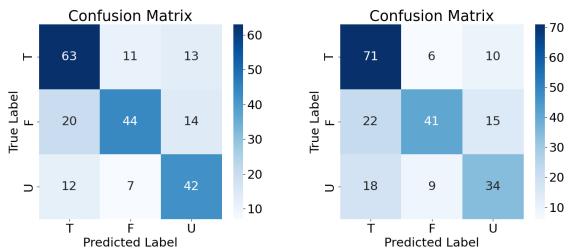

Figure 4 displays the confusion matrices. You can see that the models (both RoBERTa and GPT-4) are much better at identifying True conclusions than False or Unknown ones.

This highlights a fundamental issue with LLMs: they are biased toward confirming information present in the context. Validating that something is False (contradiction) or Unknown (lack of information) requires a more rigorous check of the “world state” defined by the premises, which seems to be harder for the attention mechanisms in Transformers to process.

Real Examples of Failure

The paper provides case studies to illustrate these failures.

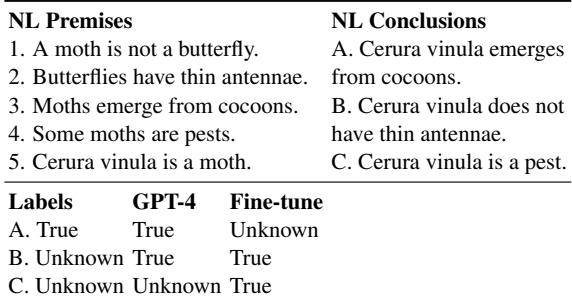

In Table 9, we see a WikiLogic example about moths and butterflies.

- The Logic: “A moth is not a butterfly.” “Cerura vinula is a moth.”

- Conclusion A: “Cerura vinula emerges from cocoons.” (Premise 3 says Moths emerge from cocoons, and CV is a moth. So, True).

- Conclusion B: “Cerura vinula does not have thin antennae.” (Premise 2 says Butterflies have thin antennae. We know CV is not a butterfly. Does that mean it doesn’t have thin antennae? No. Non-butterflies might also have thin antennae. This is a classic logical fallacy: Denying the Antecedent. The answer should be Unknown).

- Result: GPT-4 incorrectly predicts True for B. It fell for the fallacy, assuming that because butterflies have trait X, non-butterflies must not have trait X.

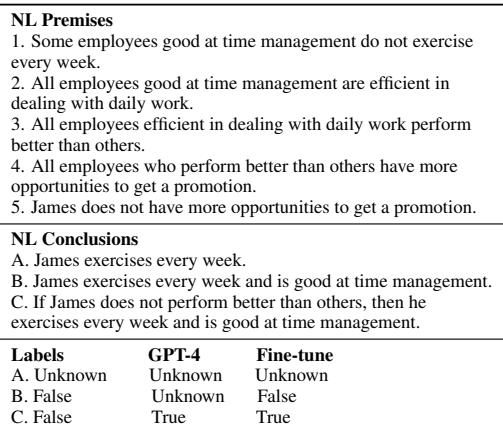

Table 10 shows a Hybrid example with even more complex quantified logic (“All employees who…”, “Some employees…”). Here, GPT-4 gets completely lost, predicting “Unknown” for a conclusion (B) that is demonstrably False based on the premises.

Conclusion

The FOLIO paper serves as a vital reality check for the AI industry. It demonstrates that while Large Language Models are fluent in human language, they are not yet reliable engines of logic.

The key takeaways from this research are:

- Language \(\neq\) Logic: A model can write perfect English (or Python) and still fail at basic deductive reasoning.

- Complexity Matters: Models perform well on shallow reasoning (1-3 steps) but degrade rapidly as the logical chain grows longer.

- Neuro-Symbolic is the Future: The best results came not from pure LLMs, but from systems that combined LLMs with formal logic solvers. This suggests the path forward may involve “hybrid” AI systems where LLMs handle the translation and formal engines handle the reasoning.

FOLIO provides a benchmark that ensures we don’t mistake fluency for intelligence. Until a model can master the “Wild Turkey” problem or the “Cerura Vinula” fallacy without external help, we have not yet solved the reasoning problem.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2209.00840/images/cover.png)