If you have ever played a massive open-world Role-Playing Game (RPG) like Skyrim, The Witcher, or The Outer Worlds, you know that the immersion depends heavily on the people you meet. Non-Player Characters (NPCs) are the lifeblood of these worlds. They give you quests, explain the history of the land, and react to your decisions.

But creating these interactions is incredibly expensive. A Triple-A game might have thousands of NPCs, each requiring unique dialogue trees that must remain consistent with the game’s lore and the current state of the player’s quest. It is a logistical nightmare that costs millions of dollars and years of writing time.

This brings us to a fascinating question: Can we use Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate, or at least assist, in writing these complex dialogue trees?

In the research paper “Ontologically Faithful Generation of Non-Player Character Dialogues,” researchers from Johns Hopkins University and Microsoft explore this exact frontier. They introduce a new dataset and a modeling framework designed to generate NPC dialogue that isn’t just grammatically correct, but “ontologically faithful”—meaning it sticks to the facts of the game world.

The Problem with Procedural Dialogue

We have had procedural text generation in games for a long time, but it has historically been shallow. Modern LLMs like GPT-3 or GPT-4 are fluent, but they are prone to “hallucination.” In a game context, hallucination is a game-breaking bug. If an NPC tells you to go to a town that doesn’t exist, or claims to be the king when they are actually a beggar, the player’s immersion is shattered.

To be useful in game development, an AI model must handle three specific complexities:

- Branching Trees: RPG dialogues aren’t linear conversations; they are trees with multiple player choices and outcomes.

- Lore Faithfulness: The NPC must embody a specific persona and know the history of the world (the ontology).

- Quest Functionality: The dialogue has a job to do—it must convey specific objectives to the player (e.g., “Find my son in Amber Heights”).

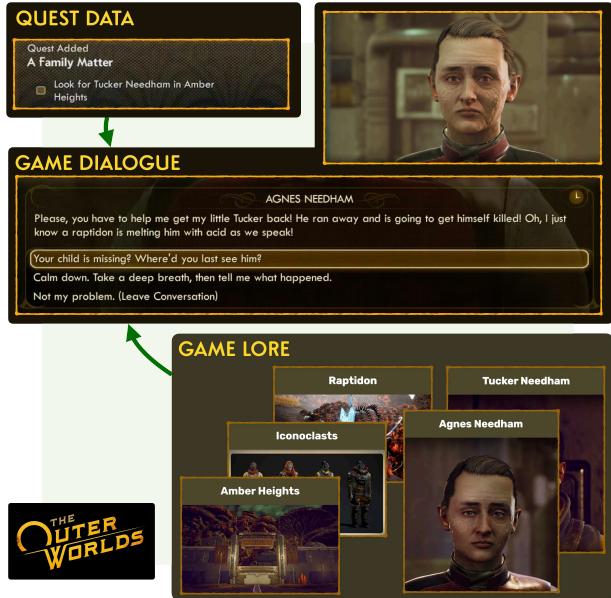

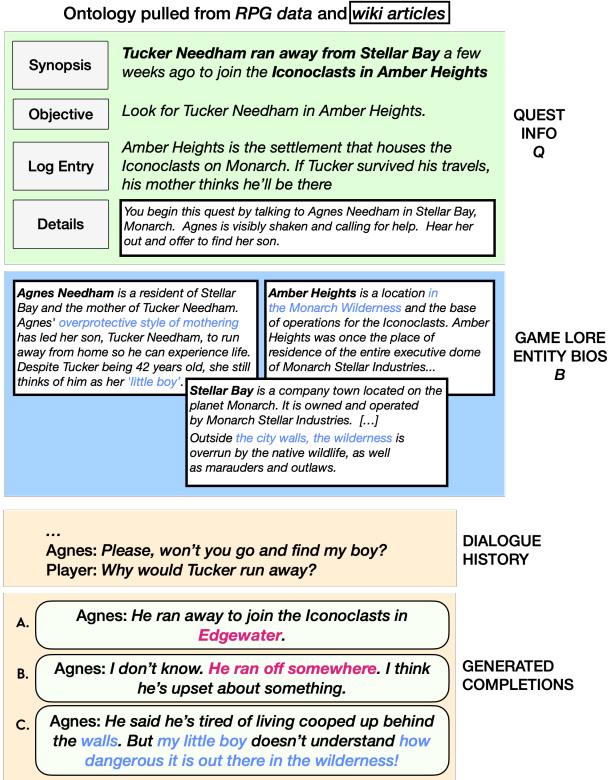

As shown below, the flow of information in a real game is complex. The dialogue sits at the intersection of quest data, the specific game lore, and the player’s choices.

Introducing KNUDGE

The first major contribution of this research is a dataset called KNUDGE (KNowledge Constrained User-NPC Dialogue GEneration).

To build a dataset that reflects real-world complexity, the researchers didn’t simulate a game; they went to the source. They extracted dialogue trees directly from Obsidian Entertainment’s hit RPG, The Outer Worlds. This game is renowned for its writing, dark humor, and complex branching narratives, making it the perfect testbed.

Anatomy of a Quest

KNUDGE consists of 159 dialogue trees from 45 side quests. But the dialogue alone isn’t enough. The researchers paired these trees with granular ontological constraints.

For every dialogue, the dataset includes:

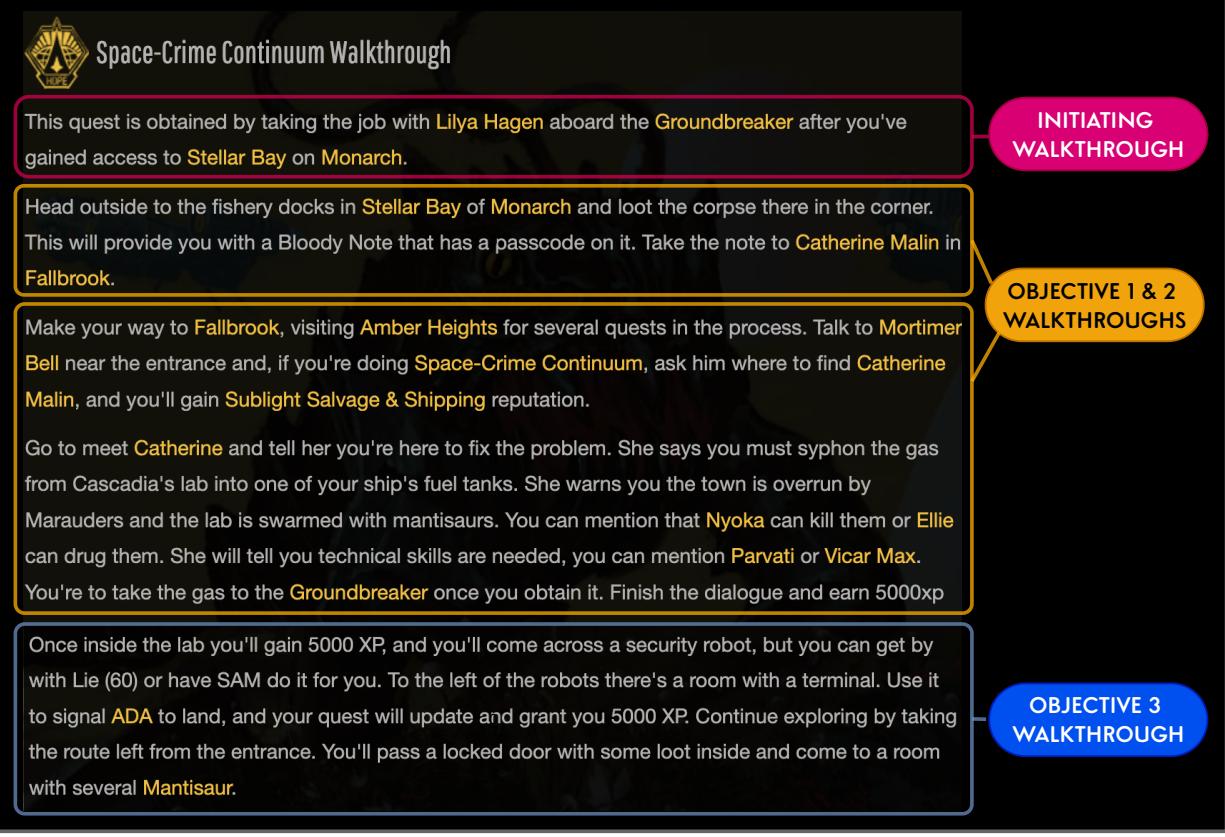

- Quest Information (Q): A synopsis, the current active objective, and “walkthrough passages” that describe what needs to happen in the conversation.

- Biographical Information (B): Detailed wikis and lore entries about the characters, locations, and groups involved.

This structure mimics the resources a human writer would have: a “bible” of the game world and a design document for the specific quest.

As you can see in Figure 6 above, the constraints are detailed. The model isn’t just told “write a quest about a missing person.” It is given specific log entries and walkthrough steps that must be reflected in the final text.

Annotating the Trees

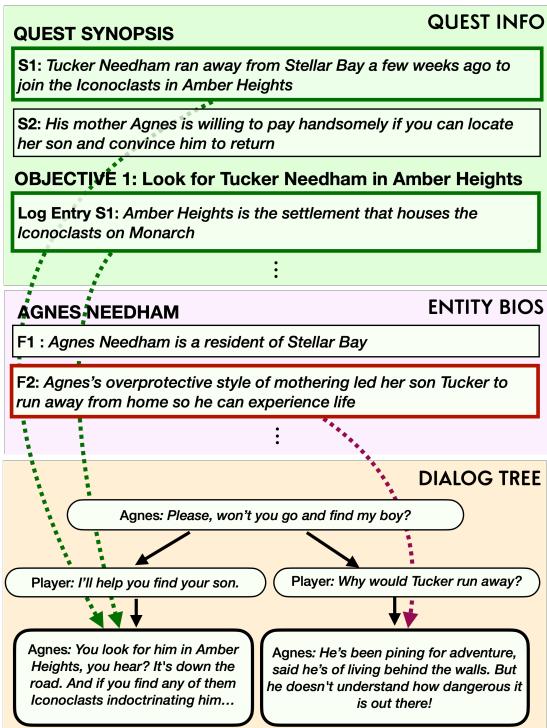

The researchers went a step further by annotating the individual nodes of the dialogue trees. They used a heuristic based on counterfactuals: If a specific piece of lore didn’t exist, would this line of dialogue still make sense?

This allows the dataset to map specific sentences in the dialogue back to the specific lore facts that support them.

In Figure 3, notice how the dialogue options (the tree at the bottom) are directly linked to the specific facts in the “Entity Bios” and “Quest Synopsis.” This mapping is crucial for training models to use information accurately rather than making things up.

The Method: DialogueWriters

With the dataset in hand, the researchers developed a set of neural methods they call DialogueWriters. The goal of a DialogueWriter is to take the game state (Quest Data Q, Biography Data B, and Participant List P) and the current conversation history, and generate the next potential responses for the NPC.

The Challenge of Non-Linearity

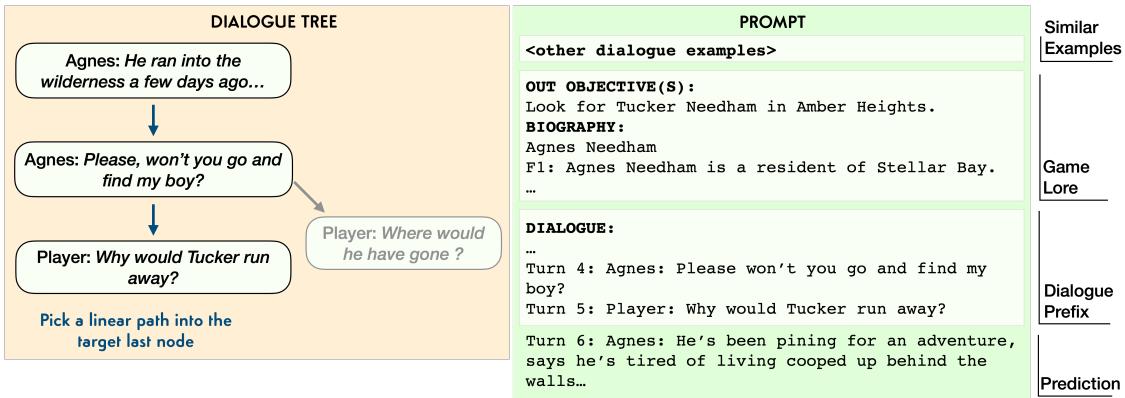

Standard Language Models read text from left to right. They expect a linear sequence. However, dialogue trees are branching graphs (and sometimes contain cycles/loops).

To solve this, the researchers used a Tree Linearization technique. When training the model to predict a specific node, they “flatten” the history by tracing the path from the start of the conversation to the current point. This turns a complex graph problem into a sequence-to-sequence problem that Transformers can handle.

Two Approaches: Supervised vs. In-Context Learning

The paper compares two primary ways of training these writers:

- Supervised Learning (SL): Fine-tuning a T5-large model. This involves updating the weights of the neural network specifically on the KNUDGE dataset.

- In-Context Learning (ICL): Using GPT-3. Instead of retraining the model, the researchers provide the Quest

Qand BiographyBdata in a massive prompt, along with a few examples of how the dialogue should look.

Figure 5 illustrates the prompting strategy. The prompt creates a “context” that includes the similar examples, the relevant game lore, and the dialogue prefix (history). The model is then asked to predict the next line.

Knowledge Selection (KS)

A key innovation here is Knowledge Selection (KS).

In a naive approach, you might just dump all the lore into the model and hope for the best. However, that often confuses the model or leads to it ignoring the constraints.

The KS models are designed to perform a two-step process:

- Select: First, identify exactly which fact from the biography or quest description is relevant to the current turn.

- Generate: Then, write the dialogue line conditioning specifically on that selected fact.

This forces the model to “show its work” and ensures that the generated dialogue is grounded in specific game data.

Figure 2 demonstrates why this is necessary. “Completion A” contradicts the lore (wrong location). “Completion B” is generic and boring. “Completion C” is the target: it advances the quest and references the specific lore about the “Iconoclasts” and the “wilderness.”

Experiments and Results

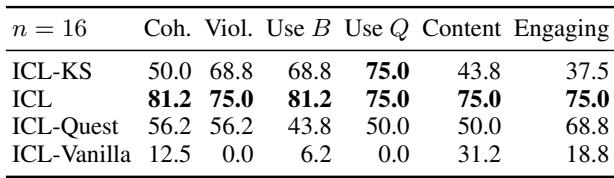

So, can AI write like a professional game designer? The researchers tested this using both automatic metrics (like BLEU scores, which measure word overlap with human reference text) and rigorous human evaluation.

Quantitative Analysis

The automatic metrics highlighted a difficulty in creative generation: the “Gold” reference (what the human writer actually wrote) is just one valid way to say something. The models often wrote valid sentences that just didn’t match the specific words of the human writer, resulting in lower scores.

However, the data showed that In-Context Learning (GPT-3) generally outperformed the fine-tuned T5 models.

Human Evaluation

Because automatic metrics are unreliable for creative writing, the researchers employed human evaluators to rate the generated dialogues on four criteria:

- Coherence: Does the conversation flow naturally?

- Violation: Does it contradict the lore?

- Biography Usage: Does it use the character’s backstory?

- Quest Usage: Does it actually advance the mission?

Table 5 shows a pairwise comparison (head-to-head wins). The results were illuminating:

- ICL (GPT-3) dominated: It was preferred over other methods for coherence and content suggestion.

- Knowledge Selection (KS) vs. Contradiction: Interestingly, the models that forced Knowledge Selection (copying facts directly) were sometimes rated slightly lower on “Non-Violation.” Why? Because sometimes forcing a complex fact into a sentence resulted in a clumsy or slightly inaccurate statement compared to the smoother, freer generation of the standard ICL model.

The “Soul” Gap

The most qualitative finding was the gap in “persona.”

While the AI models could generate coherent, factually correct dialogue, they often struggled to capture the distinct “voice” of the characters. In The Outer Worlds, an NPC might be a terrified, overprotective mother or a cynical, corporate-hating rebel.

- Gold (Human): “He ran out into the wilderness a few days ago. I warned him about the raptidons, mantisaurs, and marauders… but he didn’t listen!” (High emotion, specific lists of monsters).

- AI Model: “He left a few weeks ago. Said he was going to Amber Heights… I just know he’s going to get himself killed.” (Functional, accurate, but flatter).

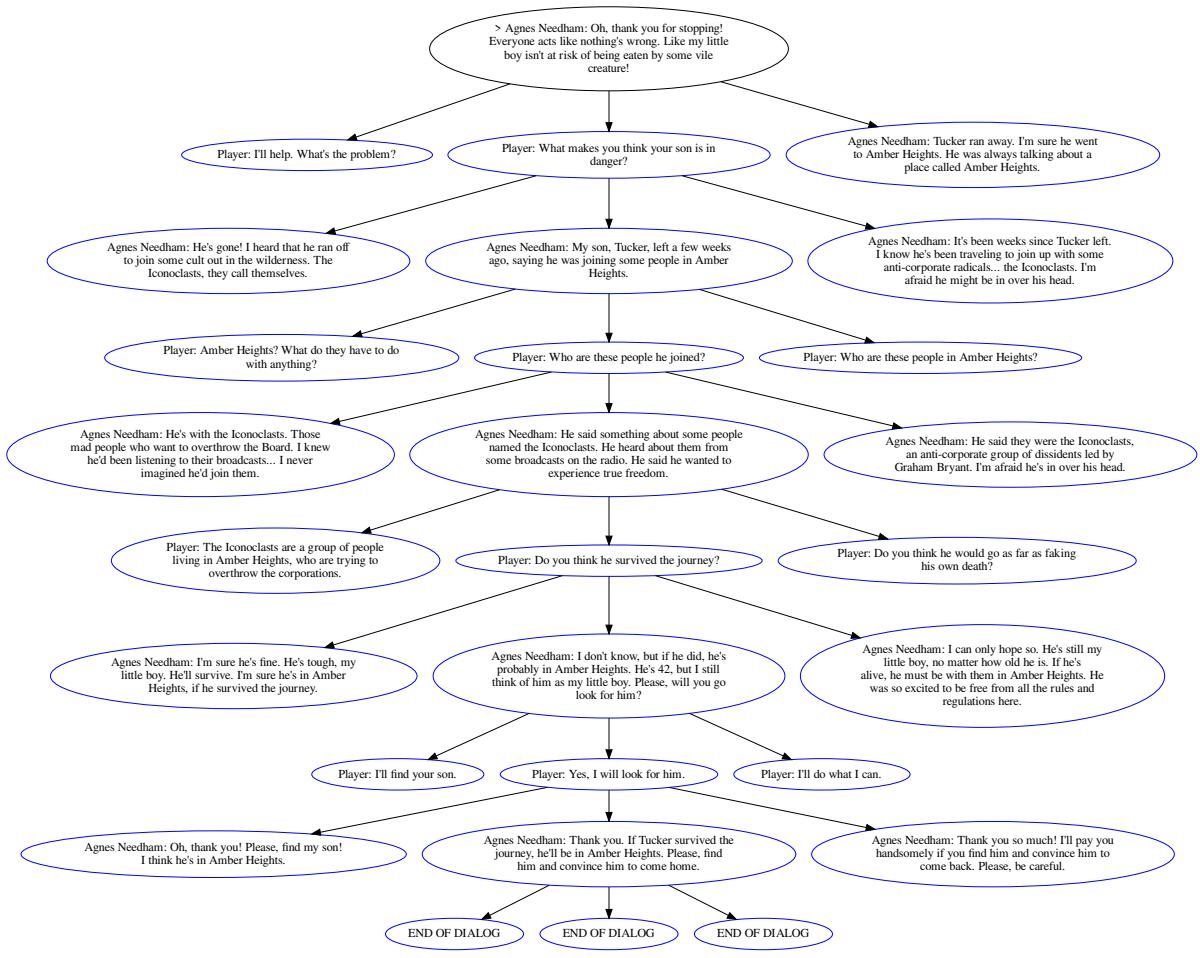

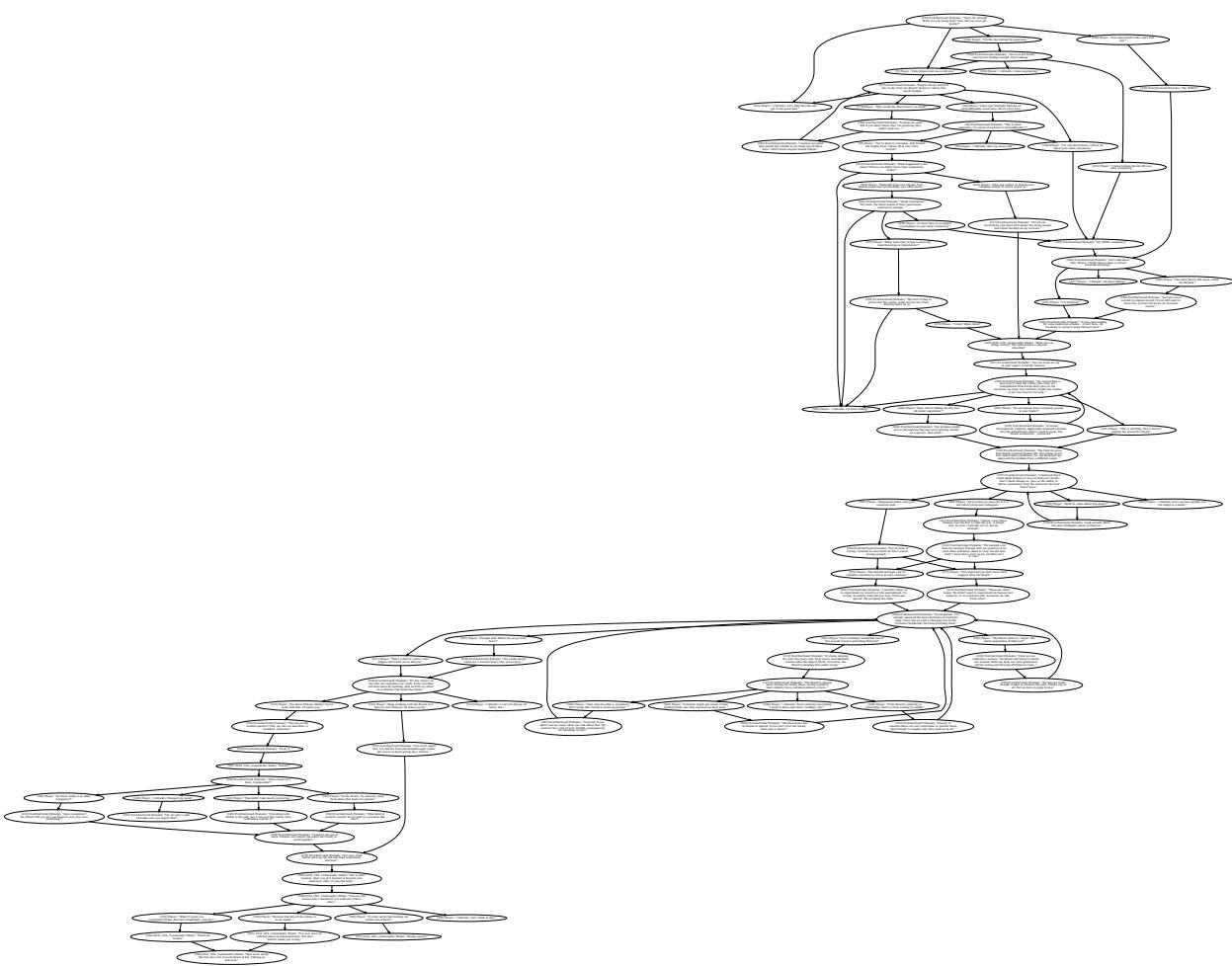

Case Study: Generating a Full Tree

To see how the models handled the ultimate challenge, the researchers tasked them with generating a full 10-round dialogue tree from scratch, given only the constraints.

Figure 16 shows an example of an AI-generated tree. It successfully branches based on player input and maintains the context of the quest (Agnes looking for her son Tucker). It reaches a logical conclusion where the player accepts the quest.

While impressive, the structure is still simpler than the hand-crafted, tangled webs found in the actual game (seen below in Figure 12). Real game trees have complex loops, skill checks (e.g., “Requires Engineering 50”), and distinct emotional shifts that the current models haven’t fully mastered.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The KNUDGE dataset serves as a reality check for AI in gaming. It moves the goalposts from “can AI write a sentence?” to “can AI maintain a consistent reality across a complex, branching narrative?”

The findings suggest that we are not yet at the point where we can press a button and generate a GOTY-winning script. The AI lacks the stylistic flair and emotional depth of professional writers. However, the DialogueWriter models prove that AI can be a powerful co-pilot.

Imagine a tool where a game designer sketches out the “beats” of a quest (the ontology), and the AI suggests a dozen variations of the dialogue tree, handling the branching logic and ensuring no lore is contradicted. The writer then polishes the dialogue, injecting the necessary personality. This “human-in-the-loop” workflow could drastically reduce the cost of development, allowing for larger, richer, and more reactive worlds than ever before.

For students of NLP and Game Design, this paper highlights that the future isn’t just about bigger models; it’s about grounding those models in structured knowledge (Ontology) to ensure they play by the rules of the world they are helping to build.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2212.10618/images/cover.png)