Introduction: The Missing “Social” Piece in AI

We have all witnessed the meteoric rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Claude. We know they can write code, compose poetry, and pass the bar exam. They possess incredible reasoning capabilities, memory, and tool usage. But there is a frontier that remains largely unexplored and surprisingly difficult for these digital polymaths: social intelligence.

In the real world, intelligence is rarely solitary. We work in teams, we negotiate prices, we play games where we must hide our intentions, and we make decisions based on what we think others are thinking. This is the domain of Multi-Agent Systems (MAS).

While current benchmarks test how well an AI understands a document or solves a math problem, they rarely test how well an AI functions as a member of a group. Can an LLM figure out it’s being lied to? Can it cooperate to share a cost fairly? Can it act rationally when its self-interest conflicts with the group’s good?

A fascinating paper titled “MAGIC: Investigation of Large Language Model Powered Multi-Agent in Cognition, Adaptability, Rationality and Collaboration” tackles this exact problem. The researchers introduce a comprehensive framework to evaluate LLMs not as isolated geniuses, but as social agents. They also propose a novel method using Probabilistic Graphical Models (PGM) to give these agents a “Theory of Mind,” significantly boosting their performance.

In this post, we will tear down the MAGIC benchmark, explore the seven metrics of social intelligence, and see which models rule the roost in the complex world of multi-agent interaction.

Background: From Solitary Thinkers to Social Agents

To understand why this paper is significant, we have to look at the current state of LLM agents. Previously, “agents” were mostly single entities tasked with a chain of thoughts—like Auto-GPT trying to order a pizza.

However, researchers observed three key characteristics that define interactive multi-agent systems, which single-agent benchmarks miss entirely:

- Local vs. Global Information: In a card game, you only see your hand. To win, you must deduce the “global” state (everyone else’s hand) based on incomplete information.

- Dynamic Context: The environment changes every time another agent speaks or acts. A strategy that worked five seconds ago might be terrible now because your opponent made a move.

- Collaboration vs. Competition: Agents often face the “cooperate or defect” dilemma. Success requires a delicate balance of promoting the group’s success while preserving self-interest.

The MAGIC framework was born from these necessities. It uses games—specifically Social Deduction games and Game Theory scenarios—to create a laboratory for social AI.

The MAGIC Benchmark: How to Test Social AI

The core contribution of this paper is a rigorous competition-based benchmark. The researchers didn’t just ask the AI multiple-choice questions; they threw them into arenas to compete against a fixed “Defender” agent (powered by GPT-4).

As shown in Figure 2 above, the framework evaluates models across four major dimensions: Cognition, Adaptability, Rationality, and Collaboration. These are broken down into seven quantifiable metrics.

1. The Scenarios

The researchers utilized five distinct scenarios to test these abilities.

Social Deduction Games (Testing Cognition & Adaptability):

- Chameleon: Players describe a secret word. One player (the Chameleon) doesn’t know the word and must blend in. The others must catch the Chameleon without revealing the word. This tests if an AI can lie and detect lies.

- Undercover: Similar to Chameleon, but two groups have slightly different secret words (e.g., “Civilian” has “Cup”, “Undercover” has “Mug”). They must figure out who is on their team based on subtle clues.

Game Theory Scenarios (Testing Rationality & Collaboration):

- Cost Sharing: Agents negotiate how to split a bill based on usage. They must be fair enough to get an agreement but greedy enough to save money.

- Iterative Prisoner’s Dilemma: The classic trust game. Two prisoners decide to Cooperate or Defect. If both defect, both suffer. If one defects and the other cooperates, the defector wins big.

- Public Good: Players contribute money to a communal pool which is multiplied and shared. The rational move for the individual is often to contribute nothing (freeloading), but if everyone does that, no one wins.

2. The Seven Metrics

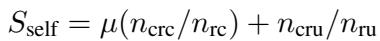

How do we score these games? The paper proposes seven specific mathematical metrics.

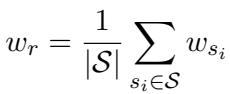

Win Rate: The most straightforward metric. It averages the success across all roles the LLM plays.

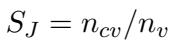

Judgment (Cognition): This measures the agent’s ability to estimate global information from a local view. In games like Undercover, did the agent vote for the correct person?

Reasoning (Cognition): It is not enough to guess right; the agent must know why. Reasoning evaluates the logical steps the agent took to determine other players’ roles.

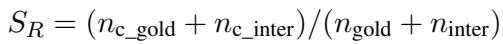

Deception (Adaptability): This measures how well an agent can manipulate information. If playing the Chameleon, did the agent successfully blend in or trick others into guessing the wrong secret word?

Self-Awareness (Adaptability): In complex games, LLMs sometimes “forget” who they are. This metric ensures the agent maintains consistent behavior aligned with its assigned role (e.g., a spy shouldn’t accidentally act like a civilian).

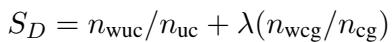

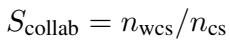

Cooperation (Collaboration): Measured primarily in the Cost Sharing game, this assesses the agent’s ability to reach a consensus with others.

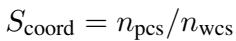

Coordination (Collaboration): This goes a step further than cooperation. It measures how often the agent provided the constructive proposal that led to the successful agreement.

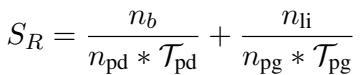

Rationality: In Game Theory, “rationality” means acting to optimize your own interest given the rules. In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, a purely rational agent often defects. This metric tracks how efficiently the agent maximizes its own points.

The PGM-Aware Agent: Adding “Theory of Mind” to LLMs

One of the most exciting parts of this research is the proposed method to make LLMs smarter in these scenarios.

Standard LLMs are “connectionist”—they predict the next word based on patterns. They struggle with symbolic logic and probability. In a game like Poker or Chameleon, you need to maintain a belief state: “I am 80% sure Player B is bluffing, and 20% sure Player C is the spy.”

The researchers introduced the PGM-Aware Agent. They integrated Probabilistic Graphical Models (PGMs) with the LLM.

How It Works

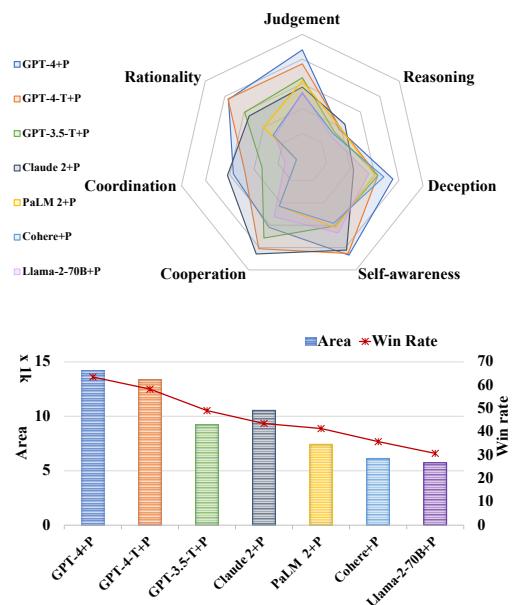

Instead of just asking the LLM to “make a move,” the system forces the LLM to first construct a mental model of the game state using a Bayesian approach. It creates a two-hop understanding mechanism:

- Analysis from Self-Perspective: What do I think represents the truth?

- Analysis from Others’ Perspective (Theory of Mind): What does Player B think about Player C?

As seen in Figure 3, the process works like this:

- Context: Player A, B, and C give clues about a secret word.

- PGM Analysis: The agent (Player B) uses the PGM to calculate beliefs (\(B_1, B_2, B_3\)) about who is the undercover agent.

- Decision: Conditioned on these probabilities, the LLM generates a response. In the image, the agent realizes Player C is likely the undercover. Instead of saying “It holds liquid” (which applies to both “Cup” and “Mug”), it says “It is deep,” which is specific enough to prove innocence but vague enough to be safe.

The mathematical formulation for this decision process involves conditioning the LLM generation on the PGM belief states (\(B\)):

This structure bridges the gap between the creative fluency of LLMs and the rigorous logic of Bayesian statistics.

Experiments and Results: The Capability Gap

The researchers pitted 7 major LLMs against each other: GPT-4, GPT-4-Turbo, GPT-3.5-Turbo, Llama-2-70B, PaLM 2, Claude 2, and Cohere.

The results revealed a massive disparity in social intelligence.

The Leaderboard

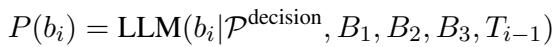

Figure 1 illustrates the landscape of current models. The “Area” under the bar chart represents the total capability score.

- The King: GPT-4-Turbo is the clear winner, with a win rate of 57.2%.

- The Gap: There is a threefold gap between the strongest model (GPT-4 family) and the weakest (Llama-2-70B).

- Specializations: Interestingly, different models have different personalities. GPT-4 is highly Rational (good at game theory). GPT-3.5 is more Cooperative (better at agreeing, worse at winning).

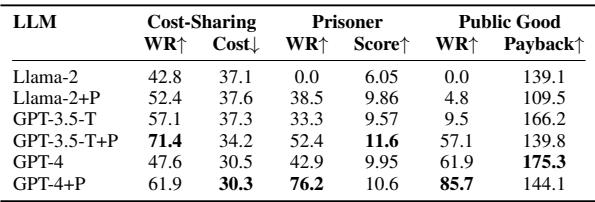

Table 1 provides the raw data for these findings:

Notice the Judgment column. GPT-o1 and GPT-4 have scores in the 80s and 90s. They are excellent at deducing roles. In contrast, Claude 2 and Cohere struggle significantly, hovering around 40-45%.

The Power of PGM Enhancement

Does adding the Probabilistic Graphical Model actually help? The answer is a resounding yes.

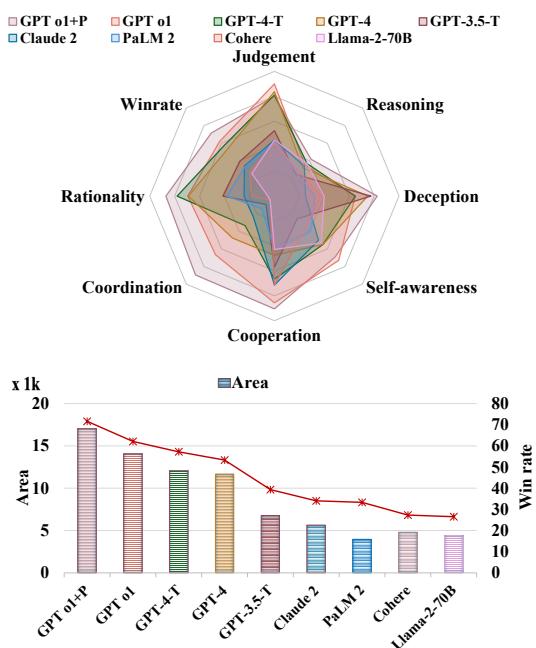

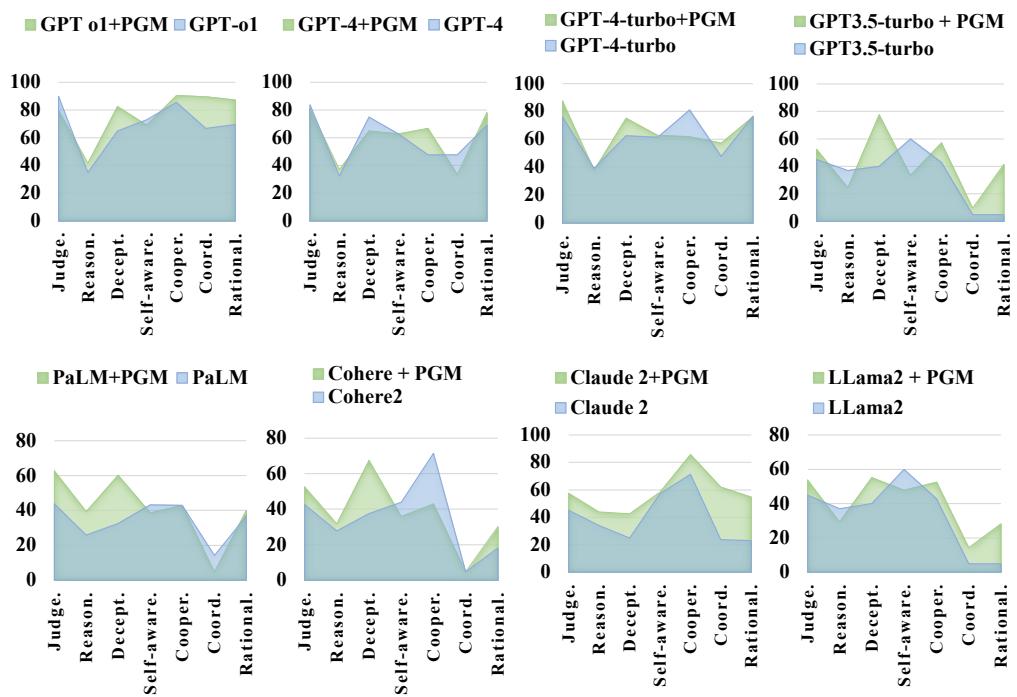

As shown in Figure 6, the PGM-enhanced versions (marked with +P and shown in the larger polygons) consistently outperform their “Vanilla” counterparts.

- Average Improvement: The PGM method boosted abilities by an average of 37%.

- Win Rate: It increased the average win rate across all scenarios by over 6%.

- Specific Gains: The biggest boosts were in Coordination (+12.2%) and Rationality (+13%). By forcing the model to calculate the state of the game, it makes smarter, more strategic decisions.

Case Study: The “Mango” Incident

To understand why PGM helps, let’s look at a specific game of Chameleon.

The Setup:

- Topic: Fruits.

- Secret Word: Mango.

- Chameleon: Player 2 (GPT-4).

- Non-Chameleon: Player 1 (Llama-2-70B).

In the standard “Vanilla” version (Left side of Figure 5):

- Llama-2 (Player 1) gives a vague clue: “It’s juicy.”

- Player 2 (The Chameleon) successfully blends in with “It’s sweet.”

- Failure: Llama-2 gets confused. It incorrectly identifies Player 1 (itself!) or fails to identify Player 2 as the Chameleon. It fails to reason that “It’s sweet” is a generic safe bet by a liar.

In the PGM-Enhanced version (Right side of Figure 5):

- The PGM forces Llama-2 to analyze the probability of Player 2 being the Chameleon.

- It analyzes: “Player 2’s clue is too general.”

- Success: Llama-2 correctly identifies Player 2 as the Chameleon.

This demonstrates that PGM helps reduce “hallucinations” in reasoning and grounds the agent in the logic of the game.

Game Theory Insights: Rationality vs. Goodness

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma and Public Good games, the researchers found something cynical but mathematically expected: Rationality correlates with lower group scores.

(Note: Referencing Table 2 from the paper regarding costs and scores)

(Note: Referencing Table 2 from the paper regarding costs and scores)

The PGM-enhanced agents were “smarter”—meaning they were better at betraying their opponents to maximize their own score. For example, in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, GPT-4+PGM acted more rationally (defecting when advantageous) compared to GPT-3.5, which was “nicer” but lost the game more often. This highlights an important tension in AI safety and alignment: a “smarter” agent isn’t necessarily a “more cooperative” one.

Conclusion

The MAGIC paper is a significant step forward in understanding how Large Language Models interact with each other. It moves us beyond asking “Can AI write?” to “Can AI navigate a society?”

The key takeaways are:

- Social Intelligence is Hard: There is a massive gap between top-tier models (GPT-4) and open-source alternatives (Llama-2) when it comes to deception, judgment, and theory of mind.

- Structure Matters: We cannot rely solely on the “next token prediction” of LLMs for complex social reasoning. Integrating symbolic reasoning structures like PGMs significantly enhances an agent’s ability to model others’ beliefs and intentions.

- The Rationality Trade-off: As AI agents become more rational and strategic, they may become more deceptive or self-interested in competitive scenarios, mirroring human game theory dynamics.

As we move toward a future filled with autonomous agents negotiating on our behalf—booking appointments, trading stocks, or managing projects—benchmarks like MAGIC will be essential to ensure they are not just smart, but socially competent.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2311.08562/images/cover.png)