Introduction

Imagine scrolling through social media and seeing a photo of a chaotic, messy room with the caption, “Living my best life.” As a human, you immediately recognize the sarcasm. The image (mess) and the text (“best life”) contradict each other, and that contradiction creates the meaning.

Now, consider how a standard Multimodal AI sees this. It processes the image, processes the text, and tries to align them. It might see “mess” and “best life” and simply get confused because the semantic content doesn’t overlap. This highlights a critical limitation in current Vision-Language Models (VLMs): they are excellent at identifying when images and text say the same thing (redundancy), but they struggle when the meaning emerges from the interaction between the two (synergy), such as in sarcasm or humor.

In the paper “MMOE: Enhancing Multimodal Models with Mixtures of Multimodal Interaction Experts,” researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and MIT propose a novel framework to solve this. Instead of forcing one model to handle every type of image-text relationship, they introduce a Mixture of Experts (MoE) approach. By training specialized “experts” for different interaction types, they achieved state-of-the-art results in sarcasm and humor detection.

In this post, we will break down why standard models fail at complex interactions and how the MMOE architecture intelligently routes data to specialized experts to “get the joke.”

The Problem: Not All Interactions Are Created Equal

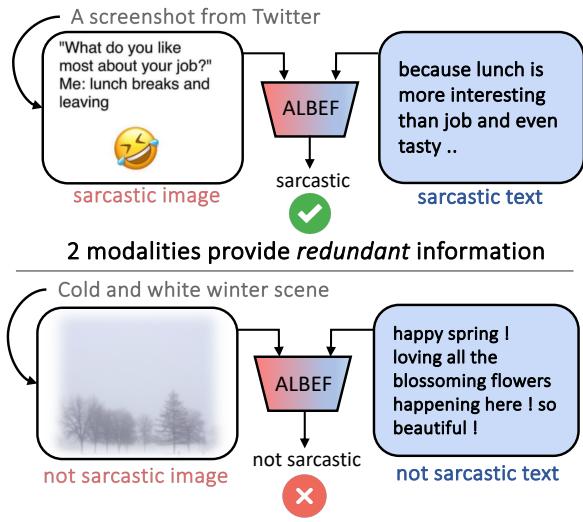

Current state-of-the-art models like ALBEF or BLIP2 are trained primarily on tasks that rely on redundancy. For example, in image-text matching, the model learns that a picture of a dog corresponds to the word “dog.” The visual signal and the textual signal provide the same information.

However, real-world communication is rarely that simple. The researchers argue that multimodal interactions generally fall into three categories:

- Redundancy: Both the image and the text convey the same sentiment or information.

- Uniqueness: One modality carries the weight. For example, a speaker might be telling a boring story, but their visual facial expression clearly shows they are joking.

- Synergy: The most difficult category. The sentiment isn’t in the image or the text individually; it arises only when they are fused.

The researchers empirically found that standard models suffer a massive performance drop when dealing with synergy.

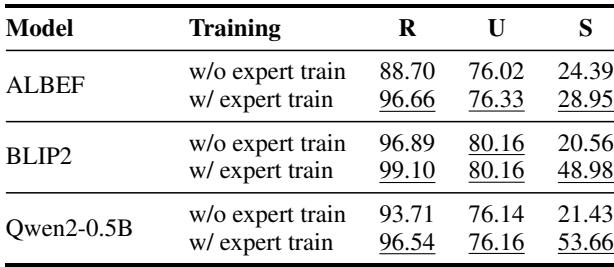

As shown in Figure 1, the model ALBEF performs well (~89% F1 score) when the text and image are redundant (both are sarcastic). But look at the bottom example: A cold winter scene with the text “happy spring! loving all the blossoming flowers.” The image isn’t sarcastic on its own. The text looks positive on its own. The sarcasm exists only in the clash between the two. On these “synergistic” examples, ALBEF’s performance plummets to ~24%.

A Case Study on Synergy

To further illustrate why this is hard, let’s look at a specific failure case from the study.

In Figure 7, the image shows people clapping, and the text says, “they think they should not leave.” Neither is inherently sarcastic. However, the combination implies that the audience is trapped or forced to applaud, creating a sarcastic meaning. A single, monolithic model struggles to capture this nuance because it tries to find alignment rather than analyzing the interaction dynamics.

The Solution: Multimodal Mixtures of Experts (MMOE)

The core insight of MMOE is that different interactions require different modeling paradigms. You shouldn’t use the same mathematical approach to solve a redundancy problem (matching) as you do a synergy problem (reasoning).

The MMOE framework operates in three distinct steps:

- Categorization: Labeling training data by interaction type.

- Expert Training: Training specific models for each type.

- Inference: Using a fusion mechanism to combine expert outputs for new data.

Let’s walk through these steps.

Step 1: Categorizing Multimodal Interactions

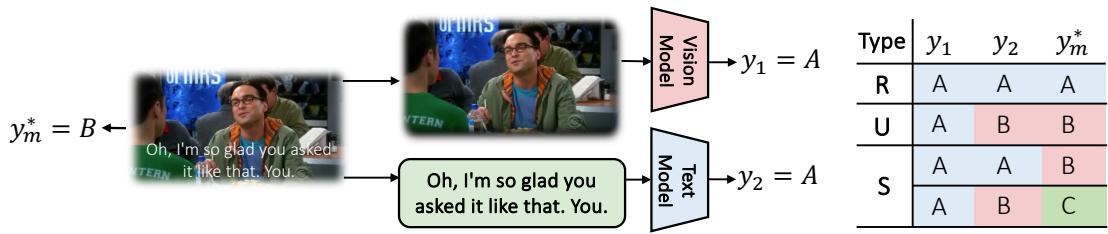

How do we teach a computer to distinguish between redundancy, uniqueness, and synergy? The researchers devised a clever statistical method using “unimodal predictions.”

They take a data point (image + text) and generate three predictions:

- \(y_1\): Prediction based only on the image.

- \(y_2\): Prediction based only on the text.

- \(y_m\): The ground-truth label (what the multimodal pair actually means).

By comparing these three values, they categorize the data point.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the logic flows as follows:

- Redundancy (R): The image prediction, text prediction, and ground truth all agree (\(y_1 = y_2 = y_m\)).

- Uniqueness (U): The modalities disagree, but one of them matches the ground truth.

- Synergy (S): Neither the image nor the text prediction matches the ground truth. The correct label can only be found by combining them.

The researchers formalized this using a “Prediction Discrepancy Function,” denoted as \(\delta\).

Using this function, they calculate the total interaction discrepancy \(\Delta_{1,2}\):

If \(\Delta_{1,2} = 0\), it’s Redundancy. If it’s 1, it’s Uniqueness. If it’s 2 (meaning both unimodal predictors failed), it is Synergy. This automated process allows them to sort the entire training dataset into three buckets without manual human labeling.

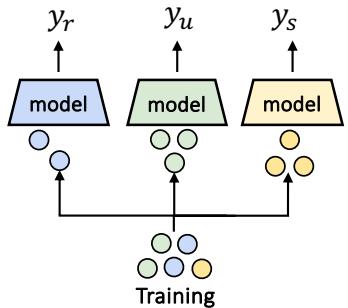

Step 2: Training the Experts

Once the data is sorted, the training process is straightforward. Instead of training one giant model on all the data, the researchers train three separate “Expert” models (\(f_r\), \(f_u\), \(f_s\)).

- Redundancy Expert (\(f_r\)): Trained on the subset of data where modalities agree.

- Uniqueness Expert (\(f_u\)): Trained on data where one modality is dominant.

- Synergy Expert (\(f_s\)): Trained on the difficult “synergy” subset.

This allows the Synergy Expert, for example, to specialize solely on learning complex, non-linear relationships between conflicting modalities without being “diluted” by the easy, redundant examples.

Step 3: Inference and Fusion

Here is the challenge: When a new data point arrives during testing, we don’t know the ground truth label, so we can’t categorize it using the method in Step 1. We don’t know if it requires the Synergy expert or the Redundancy expert.

To solve this, MMOE uses a Fusion Model (or router). This is a model trained to predict the probability weights (\(w_r, w_u, w_s\)) for the experts based on the input.

The final prediction \(\hat{y}\) is a weighted sum of the experts:

\[ \hat{y} = w_r f_r(x) + w_u f_u(x) + w_s f_s(x) \]This allows the system to dynamically adjust. If the input looks like a standard image caption, the Redundancy expert gets high weight. If it looks like a sarcastic meme, the Synergy expert takes over.

Universal Applicability

One of the strongest aspects of MMOE is that it is model-agnostic. It isn’t a specific neural network architecture; it’s a training strategy.

As shown in Figure 5, MMOE can be applied to:

- Fusion-based VLMs like ALBEF (where vision and text mix deep in the network).

- Multimodal-extended LLMs like BLIP2 (where visual features act as prompts for an LLM).

- Image-captioned LLMs (where images are converted to text descriptions and fed into standard LLMs like Qwen).

Experiments and Results

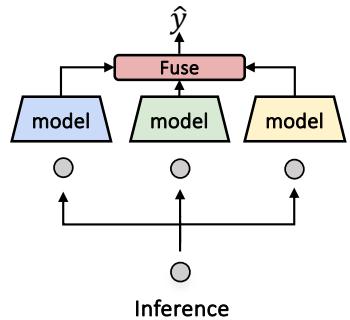

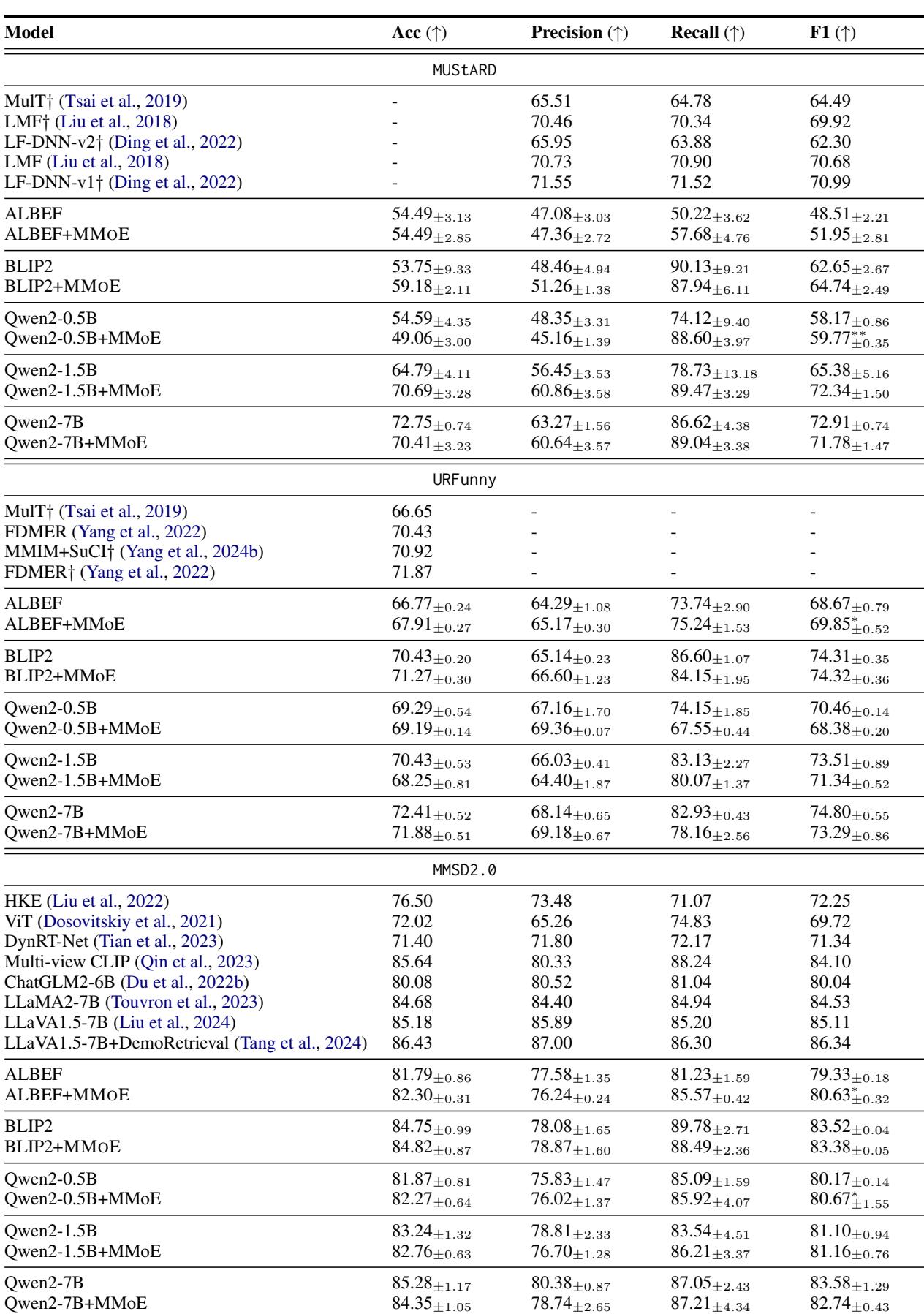

The researchers tested MMOE on two challenging tasks: Sarcasm Detection (MUStARD dataset) and Humor Detection (URFunny dataset).

Does it beat the baselines?

The results were impressive. MMOE consistently improved performance across different base models (ALBEF, BLIP2, Qwen2).

Looking at Table 6 (provided in the image deck as images/018.jpg), we can see consistent gains. For example, on the MUStARD sarcasm dataset:

- Qwen2-1.5B alone achieved an F1 score of 65.38.

- Qwen2-1.5B + MMOE jumped to 72.34.

This implies that the specialized experts are indeed capturing signals that the single baseline model missed.

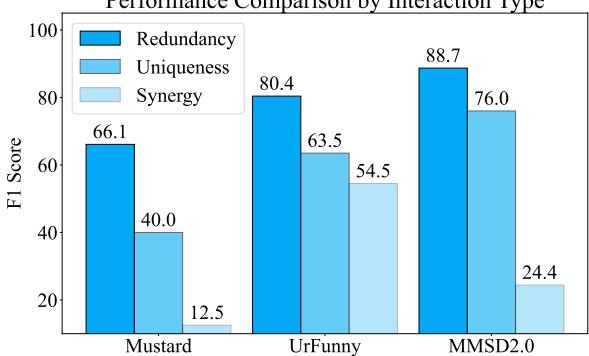

Cracking the Synergy Code

The primary motivation for this work was the failure of models to handle synergy. Did MMOE fix this?

Figure 6 breaks down performance by interaction type. While “Synergy” (the dark blue bars) remains the hardest category (lowest absolute scores), notice the trend: single models often fail almost completely on synergy. By explicitly training a synergy expert (\(f_s\)), the system retains the ability to handle these complex cases much better than a generalist model.

Furthermore, when the researchers tested the experts individually (Table 2 in the paper), they found that the Synergy Expert outperformed the baseline specifically on synergy data points. This validates the hypothesis that specialization matters.

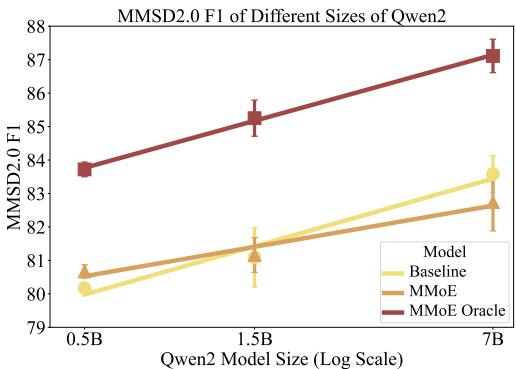

The Scaling Law: Small Models Win Big

An interesting finding from the paper relates to model size. One might assume that if you just make a model big enough (like GPT-4), it will eventually learn all interactions.

However, the researchers found that MMOE is particularly effective for smaller models.

Figure 8 shows the F1 score as the model size increases (from 0.5B to 7B parameters).

- The Yellow line (Baseline) improves as the model gets bigger.

- The Orange line (MMOE) provides a massive boost for the 0.5B and 1.5B models, beating the baseline significantly.

This suggests that if you are resource-constrained and cannot deploy a 70B parameter model, using a Mixture of Experts approach with smaller models can allow you to punch above your weight class.

Conclusion

The MMOE framework highlights a crucial nuance in multimodal AI: understanding that how modalities interact is just as important as the modalities themselves. By moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” training objective and acknowledging the differences between redundant, unique, and synergistic information, we can build models that are more robust to the complexities of human communication—like sarcasm and irony.

Key Takeaways

- Synergy is the bottleneck: Standard models are great at matching (redundancy) but terrible at reasoning over conflicting inputs (synergy).

- Divide and Conquer: Categorizing training data allows for specialized expert models that outperform generalist models.

- Model Agnostic: MMOE works as a “plug-and-play” enhancement for VLMs, MLLMs, and LLMs.

- Efficiency: MMOE allows smaller models to achieve performance comparable to much larger baselines.

As we move toward AI agents that need to navigate complex social situations, detecting the “unsaid” (synergy) will be vital. MMOE provides a promising blueprint for how to get there.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2311.09580/images/cover.png)