Introduction

Imagine you are a college student about to take a difficult exam on a subject you have never studied before—perhaps Advanced Astrophysics or the history of a fictional country. You have two ways to prepare. Option A: You lock yourself in a room for a week before the exam and memorize every fact in the textbook until your brain hurts. Option B: You don’t study at all, but during the exam, you are allowed to keep the open textbook on your desk and look up answers as you go.

Which method yields a better score?

This analogy sits at the heart of a critical debate in the development of Large Language Models (LLMs): Fine-Tuning versus Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG).

LLMs like Llama 2 or Mistral have impressive capabilities, but their knowledge is static. They only “know” what they saw during their initial training. If you ask them about an event that happened last week, or specific proprietary data from your company, they will hallucinate or plead ignorance. To fix this, we need to perform “Knowledge Injection”—the process of teaching a pre-trained model new facts.

In this post, we will dive deep into a paper by researchers from Microsoft, titled “Fine-Tuning or Retrieval? Comparing Knowledge Injection in LLMs.” We will explore the mechanics of how models learn, analyze the experimental results comparing these two methods, and uncover a surprising truth about what it actually takes for an LLM to “memorize” a new fact.

Background: What is Knowledge?

Before we can inject knowledge, we must define what it looks like for a machine. In the context of this research, knowledge isn’t about philosophical understanding; it is about factual accuracy in a multiple-choice setting.

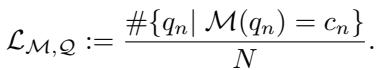

If a model “knows” a fact, it should consistently assign the highest probability to the correct answer among a set of choices. Mathematically, the researchers define the knowledge score (\(\mathcal{L}\)) of a model (\(\mathcal{M}\)) over a set of questions (\(\mathcal{Q}\)) as simple accuracy:

Here, \(N\) is the total number of questions, and \(c_n\) is the correct answer. The goal isn’t just to get a few right by chance. For a multiple-choice question with \(L\) possible answers, a model effectively possesses knowledge if its accuracy is strictly better than random guessing:

Why Do Models Fail?

Even powerful models fail to answer factual questions. The paper highlights several reasons why, but three are most relevant to our discussion on knowledge injection:

- Domain Knowledge Deficit: The model was never trained on the specific topic (e.g., a medical LLM trying to answer legal questions).

- Outdated Information: The model’s training data has a “cutoff date.” It cannot know about the winner of the 2024 Super Bowl if it was trained in 2022.

- Immemorization: The model saw the fact during training, but it appeared so rarely that the weights didn’t capture it.

To solve these deficits, we turn to our two contenders: Fine-Tuning and RAG.

The Framework: Fine-Tuning vs. RAG

The core objective of the research is to find a transformation function, \(\mathcal{F}\), that takes a base model and a new knowledge base (a text corpus), and outputs a “smarter” model.

Let’s break down the two primary ways to achieve this transformation.

1. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

RAG is the “open book test” approach. Instead of changing the model’s internal brain (its weights), we change the input we give it.

When a user asks a question, the system first acts as a librarian. It searches through an external database (the knowledge base) to find documents that are relevant to the question. It then pastes those documents into the prompt alongside the original question. The model then uses this combined context to generate an answer.

The researchers used a standard RAG setup:

- Embeddings: They used a pre-trained embedding model (

bge-large-en) to convert text documents into vectors. - Vector Store: These vectors are stored in an index (using FAISS).

- Retrieval: When a query comes in, the system finds the top-\(K\) most similar documents.

2. Unsupervised Fine-Tuning (FT)

Fine-tuning is the “cramming for the exam” approach. Here, we actually update the weights of the neural network.

The researchers specifically focused on Unsupervised Fine-Tuning (also known as continual pre-training). They took the raw text from the knowledge base and fed it into the model, training it to predict the next token, just like in the original pre-training phase.

The logic is straightforward: if the model reads the text corpus enough times, the gradient descent process should adjust the weights to “memorize” the information contained in that text.

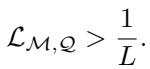

Visualizing the Comparison

The following diagram illustrates the workflow. A user asks a question (e.g., about the US President in late 2023). A base model might fail because the information is too new. However, if we inject knowledge—either by training the model on it (FT) or providing it as context (RAG)—the model should theoretically answer correctly.

Experimental Setup

To compare these methods fairly, the researchers needed diverse tasks. They chose two distinct categories of data:

1. The MMLU Benchmark (Existing Knowledge)

They selected subtasks from the Massive Multilingual Language Understanding (MMLU) benchmark, specifically in Anatomy, Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, and Prehistory.

- Why these? These are fact-heavy subjects. They minimize the need for complex reasoning and test raw knowledge storage.

- The nuance: Since these are general topics, the base models likely saw this information during their original pre-training. This tests the ability of FT and RAG to “refresh” or surface existing knowledge.

2. The “Current Events” Dataset (New Knowledge)

This is the most critical part of the experiment. The researchers created a custom dataset of questions based on US news events from August to November 2023.

- Why this matters: The models used (Llama 2, Mistral, Orca 2) had training cutoffs before this period.

- The implication: The models have strictly zero prior knowledge of these events. Any correct answers must come from the knowledge injection process (FT or RAG), allowing the researchers to test the ability to learn entirely new facts.

Results: The Clear Winner

The results were calculated using log-likelihood accuracy. Essentially, the model looks at the question and the multiple-choice options (A, B, C, D) and calculates the probability of each option completing the sentence. The option with the highest probability is selected as the answer.

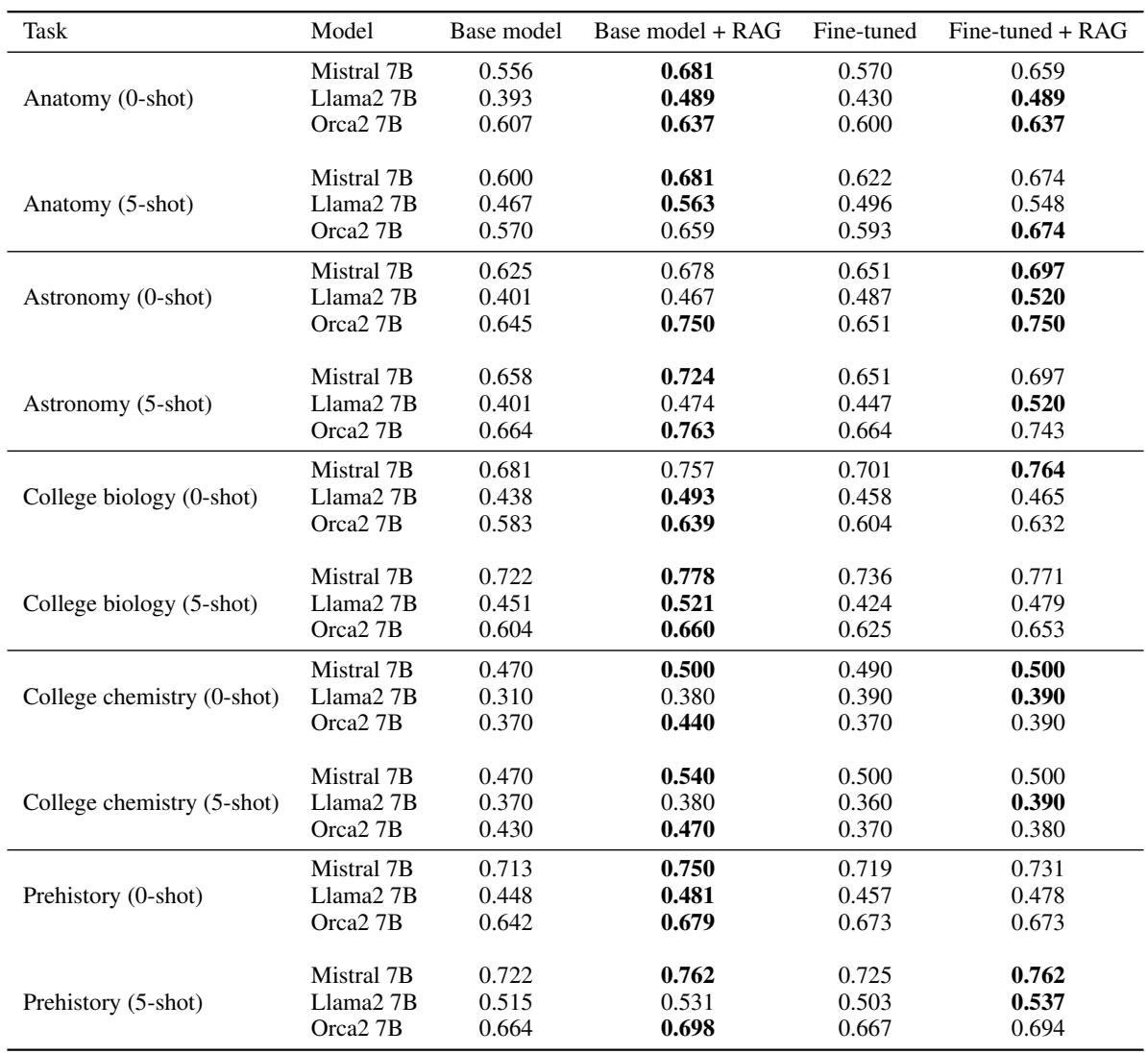

Let’s look at the performance on the MMLU datasets first.

If you examine the table above, a pattern emerges immediately. Look at the Mistral 7B rows.

- Base Model (Anatomy): 0.556 accuracy.

- Fine-Tuned: 0.570 accuracy (a tiny improvement).

- RAG: 0.681 accuracy (a massive jump).

This trend holds across almost every topic and every model. To make this easier to digest, the researchers plotted the relative accuracy gain—how much better the method is compared to doing nothing.

The Verdict: RAG dominates. In the “Llama2 7B” group, Fine-Tuning provided a roughly 2.6% gain, while RAG provided nearly 6%. For “Mistral 7B,” Fine-Tuning offered a meager 1.4% gain, while RAG offered over 6%.

Interestingly, combining the two (Fine-Tuning the model and using RAG, shown in green) didn’t consistently provide a benefit over using RAG alone. In some cases, it was actually worse.

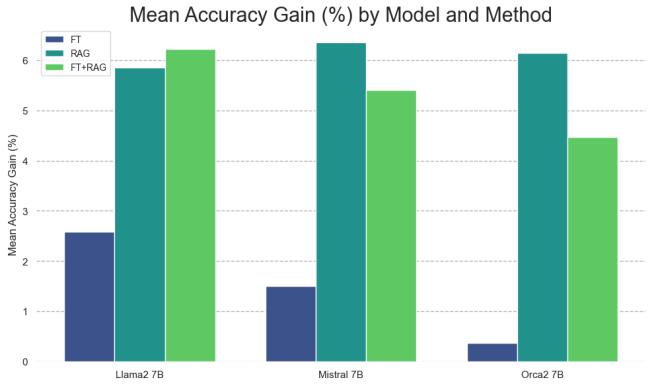

The “Current Events” Failure

The results get even more dramatic when we look at the Current Events dataset. Remember, this is information the model has never seen.

Look at the Llama2 7B column in Table 2:

- Base Model: 0.353 (Random guessing is 0.25, so it’s guessing slightly educatedly based on context).

- FT-reg (Standard Fine-Tuning): 0.219.

Wait, what? Fine-tuning the model on the news articles actually made it stupider (dropping below random chance). This is likely due to catastrophic forgetting or the model over-fitting to the text style without learning the semantic facts.

RAG, on the other hand, achieved 0.585 for Llama2 and a staggering 0.875 for Mistral. Because RAG provides the answer in the context window, the model simply needs to perform reading comprehension, which it is already good at.

The Importance of Repetition

The researchers faced a puzzling question: Why did Fine-Tuning fail so badly at learning new facts?

We often assume LLMs are like sponges—if they read a sentence once, they “know” it. This study proves that assumption wrong. The researchers hypothesized that LLMs struggle to learn new factual information through unsupervised fine-tuning unless they are exposed to variations of the fact.

To test this, they used GPT-4 to paraphrase the current events documents. They created multiple versions of the same news stories—same facts, different wording—and fine-tuned the models on this larger, repetitive dataset.

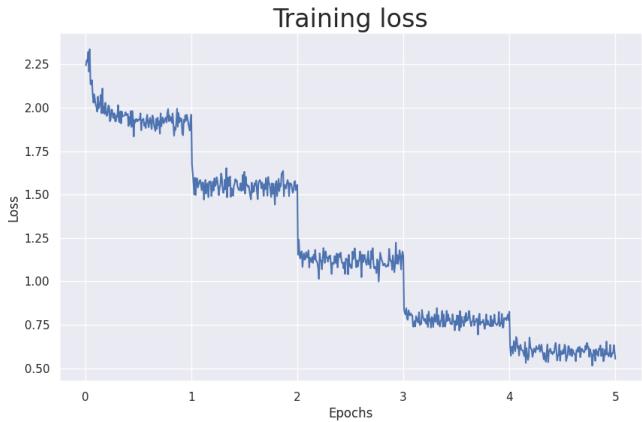

The Learning Curve

First, let’s look at the training loss. In machine learning, “loss” represents error. As the model trains over 5 epochs (viewing the data 5 times), the loss drops significantly.

The dropping loss confirms the model is “memorizing” the text. But does memorizing the text mean it understands the facts well enough to answer questions?

The “Paraphrase” Effect

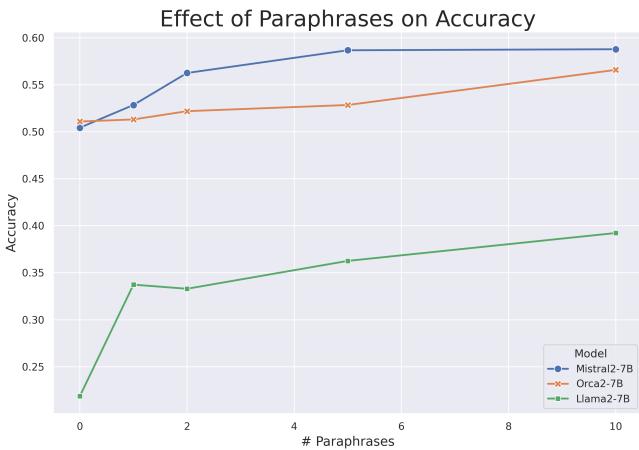

The researchers tested models trained on 0 to 10 paraphrases of the documents. The results, visualized below, confirm their hypothesis perfectly.

This graph tells a compelling story about how LLMs learn:

- 0 Paraphrases: The model barely learns anything (or gets worse).

- 1-10 Paraphrases: Accuracy is a monotonically increasing function of repetition. The more variations of the fact the model sees, the better it gets at answering questions about it.

For Llama-2 (green line), accuracy jumps from roughly 20% (worse than random) to nearly 40% simply by seeing the same facts rephrased 10 times.

This supports a concept known as the “Reversal Curse” or the difficulty of generalization. Mere memorization of a specific sentence (e.g., “Joe Biden is the President”) does not automatically grant the model the ability to answer “Who is the President?” in a multiple-choice context. It needs to see the relationship modeled in various linguistic structures to internalize the knowledge effectively.

Conclusion: The Verdict on Knowledge Injection

This paper provides a definitive answer for students and engineers deciding how to update their LLMs.

1. RAG is the King of Knowledge: If your goal is to enable an LLM to answer questions about a specific document, a new policy, or recent news, RAG is consistently superior. It is more reliable, easier to implement, and does not require expensive training. It allows the model to act as a reasoning engine over data it has explicit access to.

2. Fine-Tuning is for Style (mostly): Unsupervised fine-tuning is inefficient for injecting isolated facts. The models struggle to integrate new information unless it is hammered in with significant repetition and variation. Fine-tuning is likely better suited for adapting the style or format of a model’s output rather than its knowledge base.

3. Repetition is Key for Learning: If you must use fine-tuning to teach new facts, you cannot simply feed the model a document once. You need data augmentation. You must paraphrase, restructure, and repeat the information to force the model to learn the underlying concepts rather than just memorizing the token sequence.

For the student taking the exam, the advice is clear: Don’t try to memorize the textbook the night before (Fine-Tuning). Just bring the book to the exam (RAG). You’ll score much higher.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2312.05934/images/cover.png)