Have you ever had a text message misunderstood because the recipient couldn’t hear how you said it? The sentence “I never said he stole my bag” has seven different meanings depending on which of the seven words you emphasize.

- “I never said he stole my bag” implies someone else said it.

- “I never said he stole my bag” implies you might have thought it, but didn’t voice it.

- “I never said he stole my bag” implies he might have borrowed it.

This nuance is called prosody, often described as the “music of speech.” It includes rhythm, pitch, and loudness. While modern AI has made massive strides in Speech-to-Speech (S2S) translation and generation (think real-time translation devices or voice cloning), it often fails to capture this critical layer of meaning. Most models are “flat”—they get the words right, but the intent wrong.

In this post, we are diving into a research paper that tackles this exact problem. The researchers introduce EmphAssess, a new benchmark designed to evaluate whether S2S models can listen to an emphasized word in the input and correctly transfer that emphasis to the output, even when translating between languages.

Background: The Prosody Gap

Before we look at the solution, we need to understand the gap in current technology.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) has revolutionized speech processing. Models like AudioLM or GSLM can generate speech without needing massive amounts of labeled text. However, evaluation usually focuses on content (Did the model say the right words?) or speaker similarity (Does it sound like the original voice?).

Evaluating prosody—specifically local prosody like word emphasis—is incredibly difficult for two reasons:

- Subjectivity: Human evaluation is the gold standard, but it is expensive, slow, and subjective. What sounds emphasized to one person might sound normal to another.

- The Alignment Problem: In speech-to-speech translation (e.g., English to Spanish), you can’t just check the timestamps. If the input emphasizes the word “red” in “red car,” the output needs to emphasize “rojo” in “coche rojo.” The position of the word changes, and simple acoustic metrics don’t align perfectly.

We need an objective, automatic way to measure this “emphasis transfer.” That is where EmphAssess comes in.

The EmphAssess Pipeline

The core contribution of this paper is a modular evaluation pipeline. The goal is straightforward: take an input audio file with specific emphasis, run it through a speech model, and check if the output audio maintains that emphasis on the correct corresponding word.

The researchers broke this down into a systematic process.

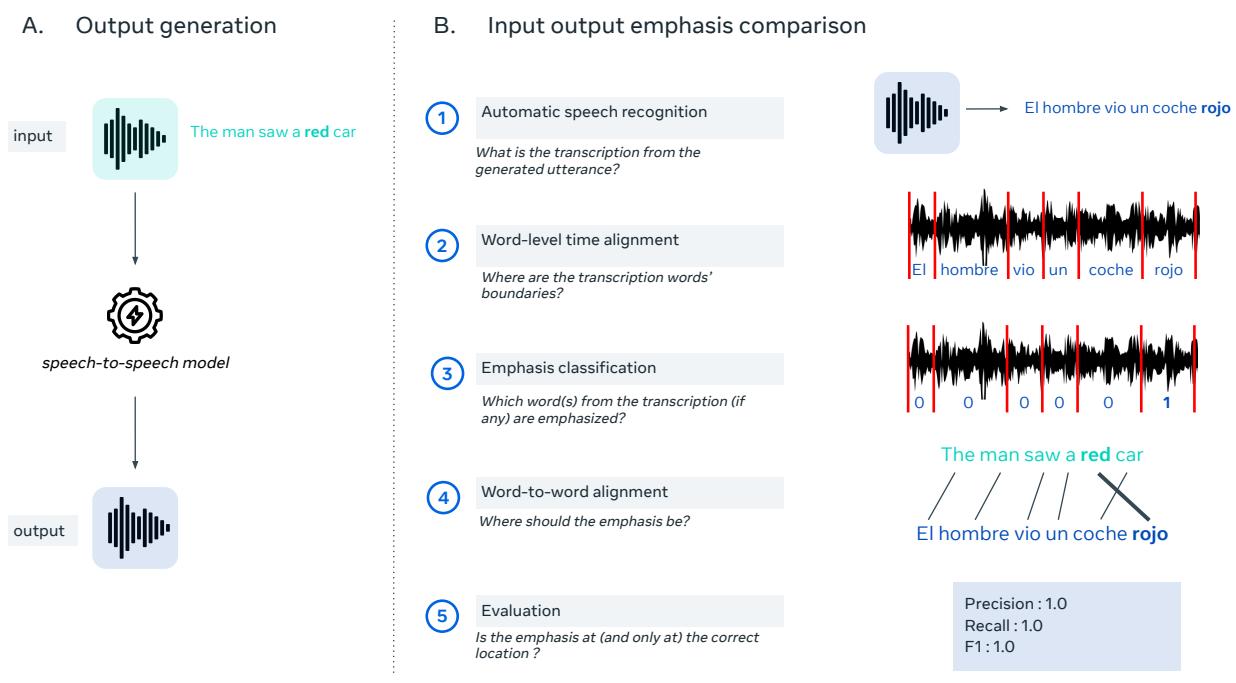

As shown in Figure 1 above, the pipeline operates in two main stages:

1. Output Generation (Left Panel)

This is the standard inference step. You feed the input audio (e.g., “The man saw a red car”) into the S2S model you want to test. The model generates an output waveform.

2. Input-Output Emphasis Comparison (Right Panel)

This is where the magic happens. The evaluation system needs to “listen” to the output and grade it. This involves five distinct steps:

- ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition): First, the system transcribes the output audio into text using a model like WhisperX.

- Forced Alignment: It aligns the text with the audio to find the exact time boundaries (start and end times) for every word in the output.

- Emphasis Classification: This is the most technically novel part of the pipeline. The system analyzes the waveform segment for each word and decides if it is emphasized or not. (We will detail the classifier, EmphaClass, in the next section).

- Word-to-Word Alignment: If the model performed a translation (e.g., English to Spanish), the system must map the words. It uses an alignment tool (SimAlign) to understand that “red” in the source matches “rojo” in the target.

- Evaluation: Finally, it compares the results. If the input had emphasis on “red,” and the classifier detects emphasis on “rojo,” it’s a success. If the emphasis landed on “coche” (car) or was missing entirely, it’s a failure.

The Engine Room: EmphaClass

To make this pipeline work, the researchers needed a reliable way to detect emphasis programmatically. Existing methods often relied on handcrafted features (like looking at raw loudness or pitch curves), which don’t generalize well across different voices or recording conditions.

The authors introduced EmphaClass, a deep learning classifier designed specifically for this task.

Architecture

Instead of building a model from scratch, they utilized XLS-R, a massive multilingual self-supervised model based on the Wav2Vec 2.0 architecture. They fine-tuned this model on a binary classification task: look at a 20ms frame of audio and predict “Is this emphasized?”

Inference

To determine if a whole word is emphasized, the model aggregates the scores of all the frames within that word’s time boundaries. If more than 50% of the frames in a word are classified as emphasized, the word receives a positive label.

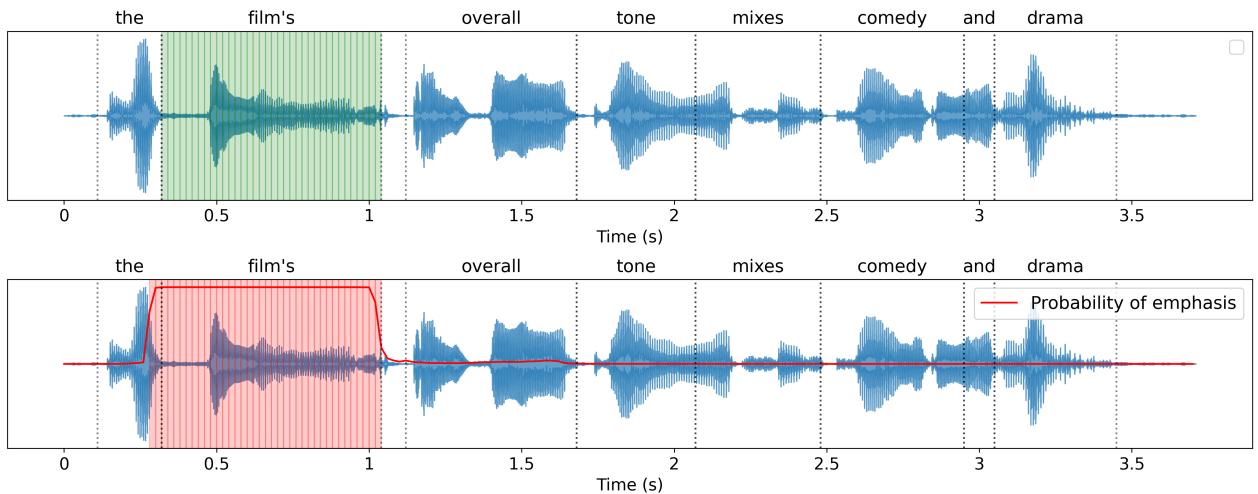

Figure 2 visualizes EmphaClass in action. The top waveform shows the ground truth—the word “film’s” is emphasized. The bottom waveform shows the model’s output probability (the red line). You can see a distinct spike in probability occurring exactly during the time segment for “film’s.” This demonstrates that the model isn’t just looking at the whole sentence; it is capable of pinpointing local prosodic changes.

Classifier Performance

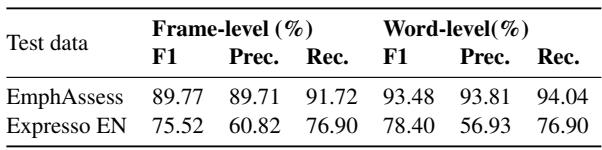

How reliable is this judge? The researchers tested EmphaClass on their own synthetic dataset (EmphAssess) and a subset of the natural speech dataset (Expresso).

As Table 1 shows, the performance is impressive. On the EmphAssess dataset, the classifier achieves a word-level F1 score of 93.48%. The performance drops on the Expresso dataset (78.4%), likely because real human speech is messier and more subtle than the synthetic voices used in the benchmark. However, for the purpose of benchmarking models, the high accuracy on EmphAssess provides a solid foundation.

Experiments & Results

With the pipeline built and the classifier trained, the researchers benchmarked several state-of-the-art models. They looked at two tasks: Speech Resynthesis (English-to-English) and Speech Translation (English-to-Spanish).

They used Precision, Recall, and F1 scores to grade the models.

- Precision: When the model adds emphasis, is it on the right word?

- Recall: Did the model fail to emphasize words that should have been emphasized?

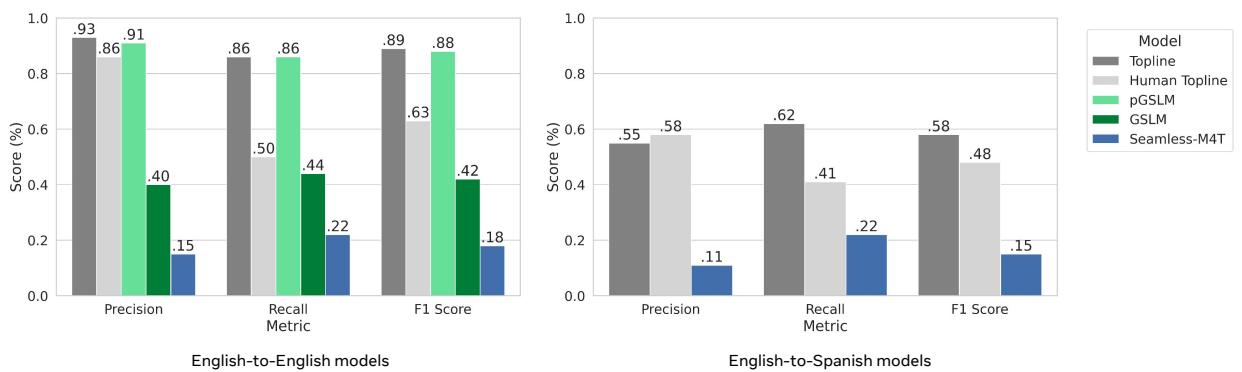

English-to-English Results

The researchers compared a “Topline” (the theoretical maximum score given the dataset constraints) against three models:

- GSLM (Generative Spoken Language Model): A standard baseline.

- pGSLM: A version of GSLM explicitly trained with prosody features (pitch and duration).

- Seamless M4T: A massive multilingual translation model.

The left chart in Figure 3 reveals a stark difference in performance:

- pGSLM (Green bars): Performs almost as well as the Topline. Because it was trained with explicit prosody targets, it is very good at preserving emphasis.

- GSLM (Dark Green): Performance drops significantly (F1 ~42%). Without explicit prosody training, the model loses much of the nuance.

- Seamless M4T (Blue): This model struggles immensely (F1 ~18%). While excellent at translation, it appears to act as a “text-to-speech” system that paraphrases content but completely discards the original audio’s stylistic cues.

English-to-Spanish Results

The right chart in Figure 3 shows the results for translation. This is a much harder task. The model must understand the emphasis in English, translate the sentence structure, and apply the emphasis to the correct Spanish word.

- The Topline itself drops to around 58% F1. This suggests that even the “gold standard” synthetic voices in Spanish were not perfectly producing detectable emphasis, or that the translation process introduces alignment errors.

- Seamless M4T performs poorly here as well (F1 ~14%). It essentially produces a flat reading of the translated text.

Cross-Language Generalization

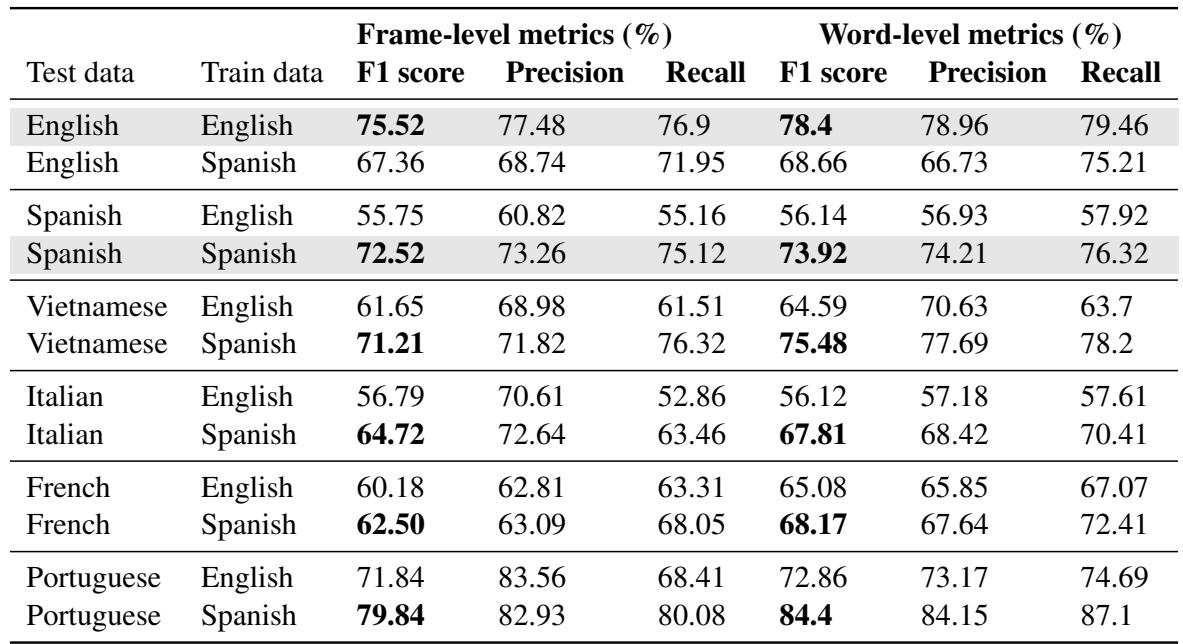

One of the most interesting secondary findings was the robustness of the EmphaClass classifier across different languages. The researchers trained the classifier on English or Spanish and tested it on other languages like Vietnamese, Italian, and Portuguese.

The table above (which corresponds to Table 2 in the paper) shows something fascinating: The Spanish-trained classifier (rows where “Train data” is Spanish) generalized remarkably well to other Romance languages (Italian, French, Portuguese) and even Vietnamese. This suggests that the acoustic cues for “importance” (louder, longer, higher pitch) might share universal properties across human languages, or at least that XLS-R representations are robust enough to capture them.

Conclusion

The EmphAssess paper highlights a critical “blind spot” in current speech AI. While models are becoming fluent in what to say, they are still learning how to say it.

The key takeaways from this work are:

- Emphasis matters: It changes meaning, and current “state-of-the-art” translation models (like Seamless M4T) effectively scrub this information from the signal.

- We can measure it: The EmphAssess pipeline proves that we don’t need to rely solely on expensive human evaluation. We can build automated systems to track prosody transfer.

- Prosody-aware training works: The success of pGSLM demonstrates that if we explicitly tell models to care about pitch and duration, they can learn to preserve emphasis.

As we move toward more naturalistic AI assistants and real-time translators, benchmarks like EmphAssess will be essential. They force developers to look beyond simple word error rates and ensure that when an AI speaks, it conveys the full intent of the message.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2312.14069/images/cover.png)