Introduction

Imagine you are watching a three-minute video of someone assembling a complex piece of furniture. At the end, I ask you: “What was the very first tool the person picked up?” To answer this, you have to remember the beginning of the video, understand the sequence of actions, and identify the object.

For humans, this is trivial. For AI, it is notoriously difficult.

While computer vision has mastered short clips (5–10 seconds), understanding “long-range” videos (minutes or hours) remains a significant hurdle. Traditional methods try to cram massive amounts of visual data into memory banks or complex spatiotemporal graphs, often hitting computational bottlenecks.

In this post, we will explore LLoVi (Language-based Long-range Video Question-Answering), a framework introduced by researchers at UNC Chapel Hill. Their approach is surprisingly simple: instead of building a larger, more complex video model, they turn the video into a book. By converting visual data into text and leveraging the reasoning power of Large Language Models (LLMs), LLoVi achieves state-of-the-art results without a single step of training.

As shown in Figure 1, while traditional models like FrozenBiLM struggle to capture the full sequence of a long activity (cleaning a dog mat), LLoVi accurately synthesizes the step-by-step process.

The Problem with Long-Range Video

Why is long-range video question answering (LVQA) so hard? It comes down to the “context window” and information density. A video is a sequence of thousands of images (frames). Processing every pixel of every frame for minutes on end requires massive computational memory.

To get around this, previous researchers developed complex architectures involving:

- Memory Queues: Storing features from the past to recall later.

- State-Space Layers: Mathematical models to compress sequences.

- Graph Neural Networks: Mapping relationships between objects across time.

However, a secondary problem has plagued the field: the datasets themselves. Many “video” datasets allow models to cheat.

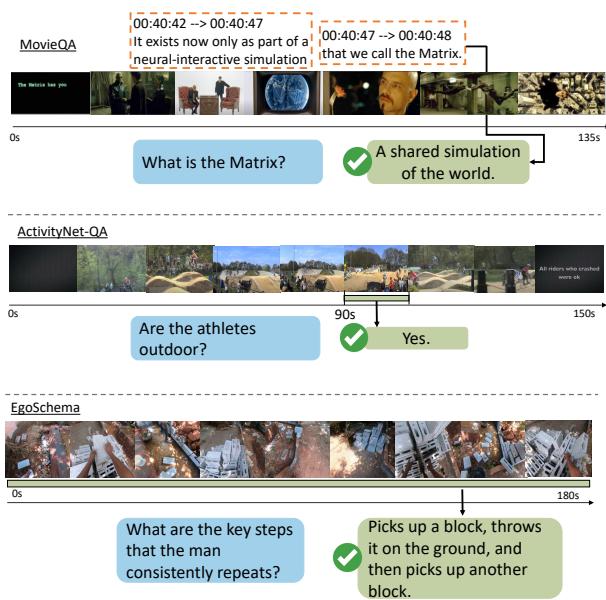

As illustrated in Figure 4, datasets like MovieQA often rely on subtitles, meaning the model is just reading the script, not watching the movie. Others, like ActivityNet-QA, ask questions that can be answered by glancing at a single 1-second clip (e.g., “Are they outdoors?”), rendering long-term reasoning unnecessary.

The LLoVi paper focuses heavily on EgoSchema, a benchmark designed to be “un-cheatable.” It consists of very long egocentric (first-person) videos where the answer requires synthesizing information from across the entire timeline, and it cannot be solved by language bias alone.

The LLoVi Framework: A Two-Stage Approach

The core insight of LLoVi is that we don’t need a new video architecture; we need a better way to interface video with existing intelligent systems. The framework decouples visual perception (seeing what is happening) from temporal reasoning (understanding how it fits together).

The method operates in two distinct, training-free stages.

Stage 1: Short-Term Visual Captioning

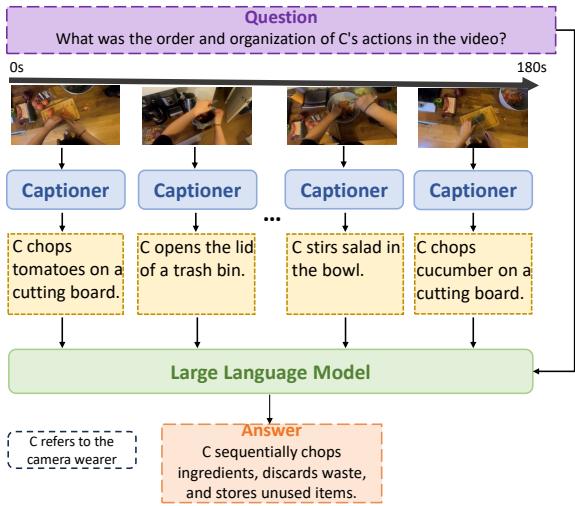

First, the long video is chopped into dense, short clips (ranging from 0.5 to 8 seconds). These clips are fed into a specialized “Visual Captioner”—a model trained to look at an image or short clip and describe it in text.

Models used here include:

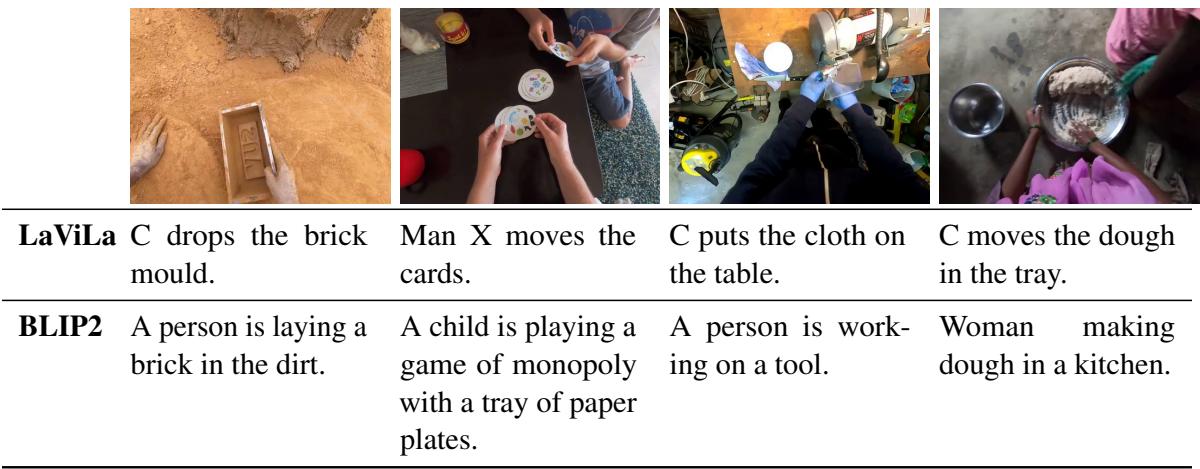

- LaViLa: A model specialized in egocentric (first-person) video, great at describing actions.

- BLIP-2 / LLaVA: Strong image-based models that describe static scenes.

Stage 2: LLM Reasoning

Once the video is converted into a sequential list of textual descriptions (captions), the “visual” problem transforms into a “long-context language” problem. These captions are concatenated chronologically and fed into a Large Language Model (like GPT-4 or GPT-3.5). The LLM is then prompted to answer the question based on the “story” the captions tell.

Figure 2 visualizes this flow. The system takes a 180-second video of cooking, breaks it down into granular descriptions (e.g., “chopping tomatoes,” “stirring salad”), and the LLM deduces the logical order of actions.

This approach bypasses the memory bottleneck of processing pixels. Text is lightweight. An LLM can easily read a description of a 10-minute video, whereas a Vision Transformer would crash trying to process the raw frames.

The “Multi-Round Summarization” Prompt

Simply dumping hundreds of captions into an LLM does not guarantee a good answer. The generated captions are often noisy, repetitive, or irrelevant to the specific question being asked.

For example, if the question is “What ingredient did he add after the salt?”, but the captions are filled with descriptions of the kitchen tiles or the color of the chef’s shirt, the LLM might get distracted (hallucinate).

To solve this, the authors introduce a Multi-Round Summarization Prompt.

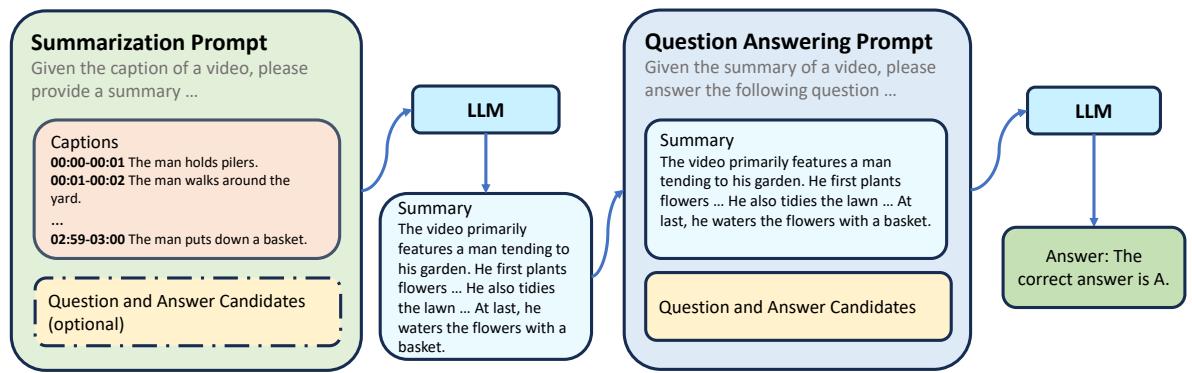

As shown in Figure 3, this strategy splits the reasoning into two steps:

- Summarization Round: The LLM is given the raw captions and the Question (\(Q\)). It is asked to generate a summary of the video specifically relevant to answering \(Q\).

- QA Round: The LLM is given the clean summary (from step 1) and asked to provide the final answer.

This acts as a filter. By asking the LLM to summarize first, it forces the model to sift through the noise and identify key events, discarding irrelevant details before attempting to solve the logic puzzle.

Empirical Analysis: What Makes LLoVi Work?

The researchers conducted extensive experiments on the EgoSchema dataset to determine which components matter most.

1. The Choice of Visual Captioner

Not all captioners are created equal. The study compared generic image captioners (like BLIP-2) against video-specific ones (like EgoVLP and LaViLa).

The qualitative comparison in Table 11 (above) highlights the difference. LaViLa (developed for egocentric video) produces concise, action-focused captions (e.g., “Person B talks to C”). In contrast, image-based models like BLIP-2 often fixate on objects (e.g., “a blue shirt”) rather than the temporal flow of events.

Quantitatively, LaViLa achieved the highest accuracy (55.2%), proving that the quality of the “translation” from video to text is the bottleneck of this framework.

2. LLM Performance vs. Cost

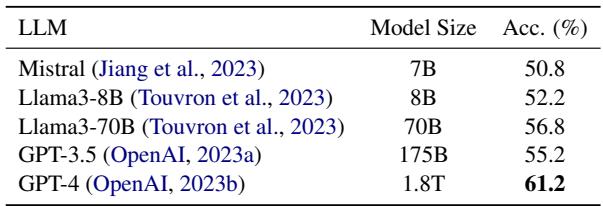

Does the brain matter? Yes. The researchers tested LLoVi with various LLMs.

GPT-4 significantly outperformed other models, achieving 61.2% accuracy (Table 2). This confirms that long-range video understanding is largely a reasoning task once the visual data is textualized. However, GPT-3.5 remains a strong, cost-effective contender at 55.2%.

3. Video Sampling Strategy

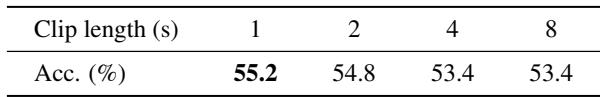

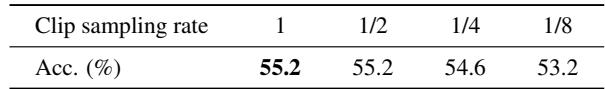

How often should we look at the video? The researchers analyzed clip lengths and sampling rates.

Table 3 shows that 1-second clips yield the best performance. Longer clips (e.g., 8 seconds) result in a loss of fine-grained detail.

However, Table 4 reveals an interesting efficiency hack. You don’t need to caption every second. Sampling a 1-second clip every 8 seconds (leaving gaps) dropped accuracy by only 2.0% while making the system 8 times faster. This trade-off is vital for real-world applications where speed is a priority.

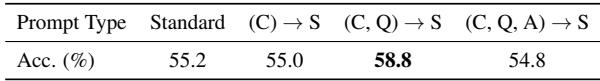

4. The Impact of Prompting

The most significant software innovation in LLoVi is the prompting strategy discussed earlier.

Table 5 confirms the hypothesis: Standard prompting (just giving captions + question) yields 55.2%. However, the (C, Q) \(\rightarrow\) S strategy (Summarize Captions \(C\) given Question \(Q\), then answer) boosts accuracy to 58.8%. This suggests that the LLM needs to know what it’s looking for while it summarizes the video log.

Qualitative Results: Success and Failure

It is helpful to look at specific examples to understand how the Multi-Round Summarization prompt fixes errors.

In Figure 9, the standard prompt fails. The raw captions are flooded with repetitive actions (“picking up clothes,” “dropping clothes”). The LLM gets confused and guesses the user is “packing a bag.”

However, in the Multi-round approach (bottom), the LLM first generates a summary: “Throughout the video, C is seen engaging in tasks related to laundry…” This abstraction layer allows the second stage to correctly identify the activity as “doing laundry.”

Generalization to Other Benchmarks

While EgoSchema was the primary testbed, LLoVi is not a one-trick pony. The researchers applied the framework to other challenging datasets like NExT-QA (identifying causal and temporal relationships) and IntentQA (understanding human intent).

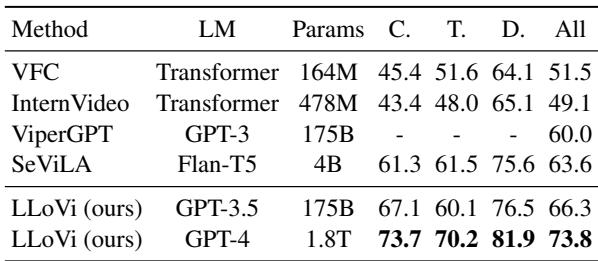

On NExT-QA (Table 8), LLoVi achieves 73.8% accuracy, smashing the previous state-of-the-art (SeViLA) by 10.2%. This is a massive margin in the field of computer vision.

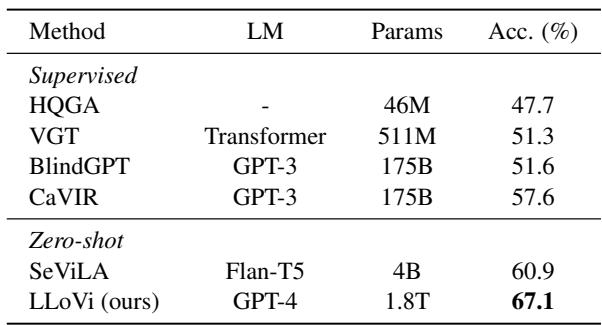

Similarly, on IntentQA (Table 9), LLoVi dominates both supervised and zero-shot baselines.

Conclusion

The LLoVi paper teaches us a valuable lesson about modern AI: Simplicity and modularity often beat complexity.

Instead of training massive, end-to-end video networks that require expensive hardware and specialized datasets, LLoVi decomposes the problem. It lets computer vision do what it does best (describe a scene) and lets LLMs do what they do best (reason over long sequences of information).

Key Takeaways:

- Decomposition is Powerful: Splitting LVQA into “Captioning” and “Reasoning” stages allows the use of state-of-the-art tools for both.

- Training-Free SOTA: You don’t always need to retrain models. LLoVi achieves top results on EgoSchema and NExT-QA without fine-tuning, simply by prompting correctly.

- Prompt Engineering Matters: The “Multi-round Summarization” strategy demonstrates that how you ask the LLM is just as important as the data you give it.

As visual captioners become more detailed and LLMs become smarter (and cheaper), frameworks like LLoVi will likely become the standard for analyzing the massive amounts of video data generated every day.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2312.17235/images/cover.png)