Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have revolutionized how we interact with text. We treat them as omniscient oracles—capable of answering complex questions, writing code, and summarizing novels. Naturally, we expect them to be exceptional translators. If an LLM knows who a specific celebrity is when asked in a Q&A format, it should surely be able to translate a sentence containing that celebrity’s name, right?

Surprisingly, the answer is often no.

Recent research has uncovered a fascinating and problematic phenomenon: a misalignment between an LLM’s general understanding (what it knows when asked directly) and its translation-specific understanding (how it acts when asked to translate). The model might know a fact perfectly well, but when placed in the context of a translation task, it suffers from “generalization failure,” reverting to literal or incorrect translations.

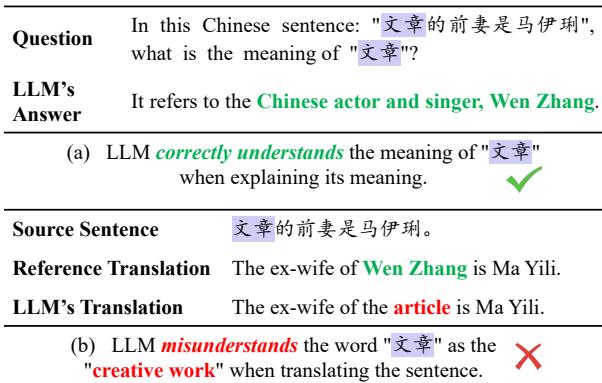

Consider the example below. When asked directly, the LLM correctly identifies “Wen Zhang” (文章) as a Chinese actor. However, when translating a sentence containing that name, the model treats “文章” literally as “article,” resulting in a nonsensical translation.

To solve this, researchers from the Harbin Institute of Technology and Peng Cheng Laboratory have proposed a novel framework called DUAT (Difficult words Understanding Aligned Translation). By mimicking the workflow of a senior human translator—identifying difficult concepts, interpreting them, and then translating—DUAT significantly improves translation quality.

In this post, we will deconstruct the DUAT paper, exploring how it bridges the gap between an LLM’s knowledge and its translation output.

The Problem: Understanding Misalignment

Before diving into the solution, we must understand the core issue. LLMs are trained on massive amounts of data, giving them both broad world knowledge and specific linguistic skills. However, these two capabilities do not always talk to each other.

When you prompt an LLM to translate, it often enters a specific “mode” based on the patterns it learned during training. It might act like a junior translator, focusing on word-for-word substitution rather than the deeper meaning it actually possesses.

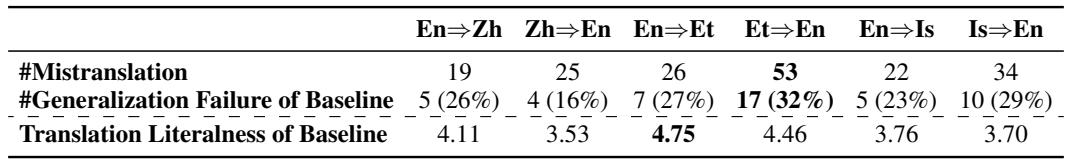

The researchers termed this Generalization Failure. In their experiments, they found that these failures account for 16% to 32% of all mistranslations. The model isn’t lacking knowledge; it simply fails to access that knowledge while in “translation mode.”

The Traditional Approach vs. The Gap

Standard LLM-based machine translation usually relies on In-Context Learning (ICL). You provide the model with a few examples (demonstrations) and the source sentence, and ask it to generate the target sentence.

Mathematically, this looks like this:

Here, the model tries to maximize the probability of the translation (\(\hat{y}\)) given the examples (\(\mathcal{E}^{mt}\)) and the source sentence (\(x\)). While effective for simple sentences, this method encourages the model to just “follow the pattern,” often bypassing the deep comprehension needed for complex metaphors, idioms, or entities.

The Solution: DUAT

The researchers propose DUAT to force the model to access its general understanding before committing to a translation. This process mimics a senior translator who, upon encountering a tricky phrase, pauses to analyze its meaning in context before translating.

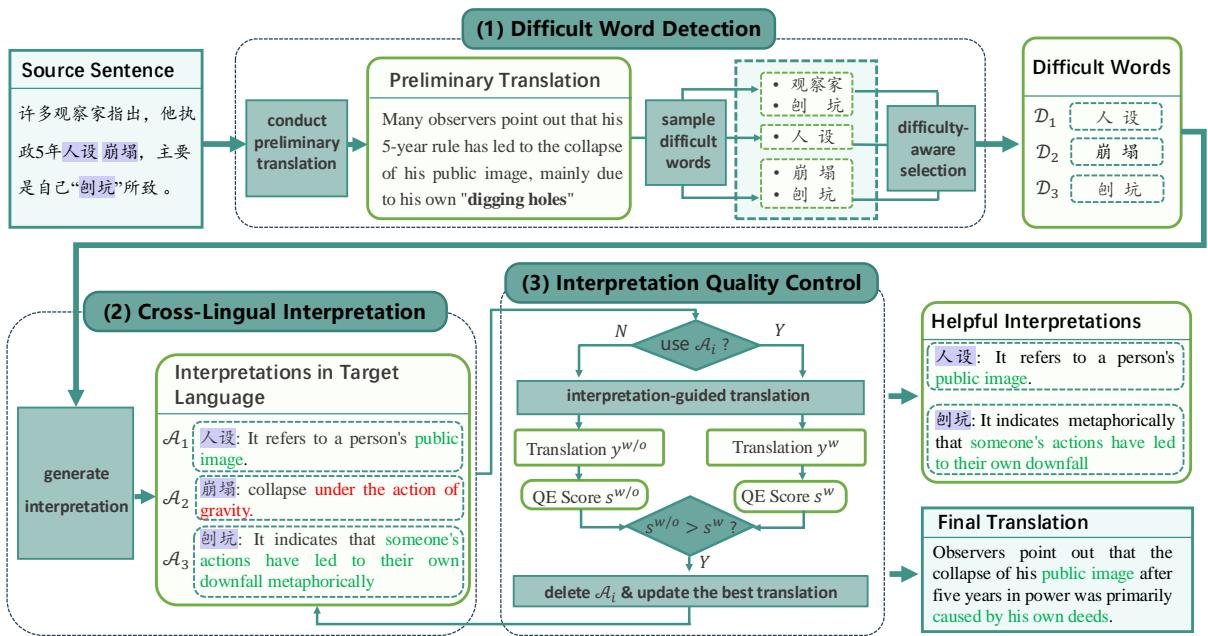

The DUAT framework consists of three distinct steps:

- Difficult Word Detection: Finding the parts of the sentence prone to error.

- Cross-Lingual Interpretation: Asking the model to explain those words.

- Interpretation Quality Control (IQC): Filtering out bad explanations to guide the final translation.

Let’s look at the complete workflow:

As shown above, the system first spots difficult words (like “human setting” or specific metaphors), generates an interpretation (e.g., “it refers to a person’s public image”), and uses that interpretation to generate a nuanced translation rather than a literal one.

Step 1: Difficult Word Detection

How does the model know which words are “difficult”? The researchers developed two approaches: DUAT-I (Intrinsic) and DUAT-E (External).

DUAT-I simply asks the LLM to identify difficult words based on a draft translation. However, LLMs often have overconfidence issues—they don’t always know what they don’t know.

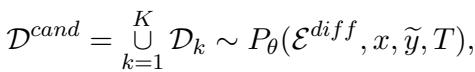

DUAT-E is the more robust approach. It uses an external tool and a sampling strategy. First, the model generates multiple candidate sets of difficult words by sampling the output several times (using a temperature setting to encourage diversity).

Next, to determine which words are genuinely problematic, the system uses Token-level Quality Estimation (QE). Usually, QE checks if a translation is good without needing a reference human translation. Here, the researchers flip the script: they use QE to check how well the source words align with the draft translation.

If a source word has a high misalignment score (\(\phi(d)\)), it means the draft translation likely failed to capture its meaning. These words are flagged for the next step.

Step 2: Cross-Lingual Interpretation

Once the difficult words are identified (\(D\)), the model is prompted to interpret them. Crucially, DUAT asks the model to provide these interpretations in the target language.

Why the target language? If we are translating from Chinese to English, explaining a Chinese idiom in English helps align the model’s internal understanding directly with the output space.

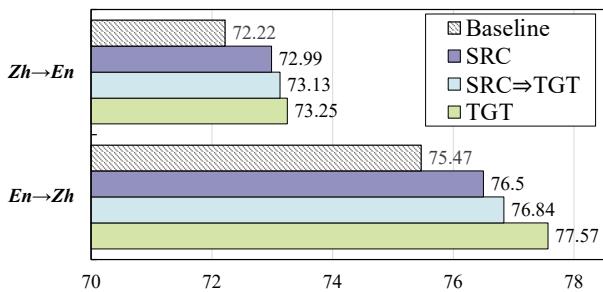

The researchers found that this “Cross-Lingual Interpretation” is far more effective than defining the word in the source language. As shown in the analysis below, interpretations in the target language (blue bars) consistently outperform those in the source language (purple bars).

Step 3: Interpretation Quality Control (IQC)

There is a risk: what if the LLM hallucinates? If the model generates a wrong interpretation, it could mislead the translator, resulting in an even worse output.

To prevent this, DUAT employs Interpretation Quality Control. The system performs a refinement process. It attempts to translate using the interpretations. It then uses a sentence-level Quality Estimation scorer to grade the result.

If removing a specific interpretation improves the QE score, that interpretation is discarded. The final translation is generated using only the “helpful” interpretations.

Experimental Setup: Challenge-WMT

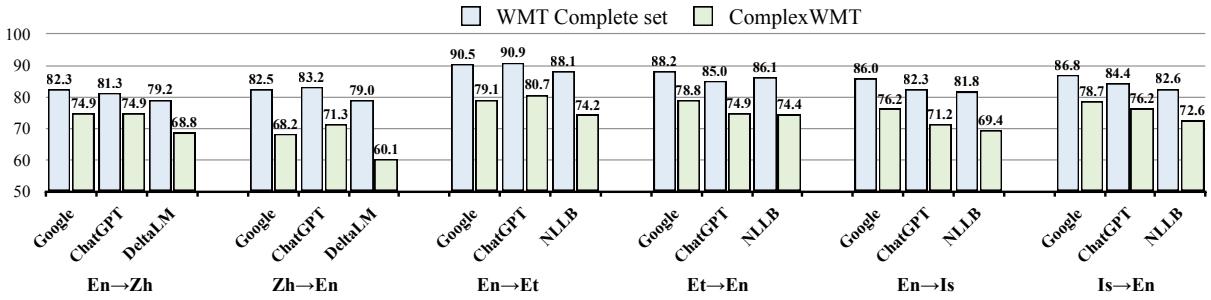

Standard translation benchmarks are often too easy for modern LLMs, masking their generalization failures. To truly test DUAT, the authors constructed a new benchmark called Challenge-WMT.

They collected sentences from historical translation competitions (WMT) that multiple state-of-the-art systems (like Google Translate and ChatGPT) historically struggled with.

As visible in Figure 8 above, performance drops significantly on this dataset (the green bars) compared to standard datasets (blue bars), confirming that Challenge-WMT effectively targets the “hard” cases where alignment issues occur.

Results and Analysis

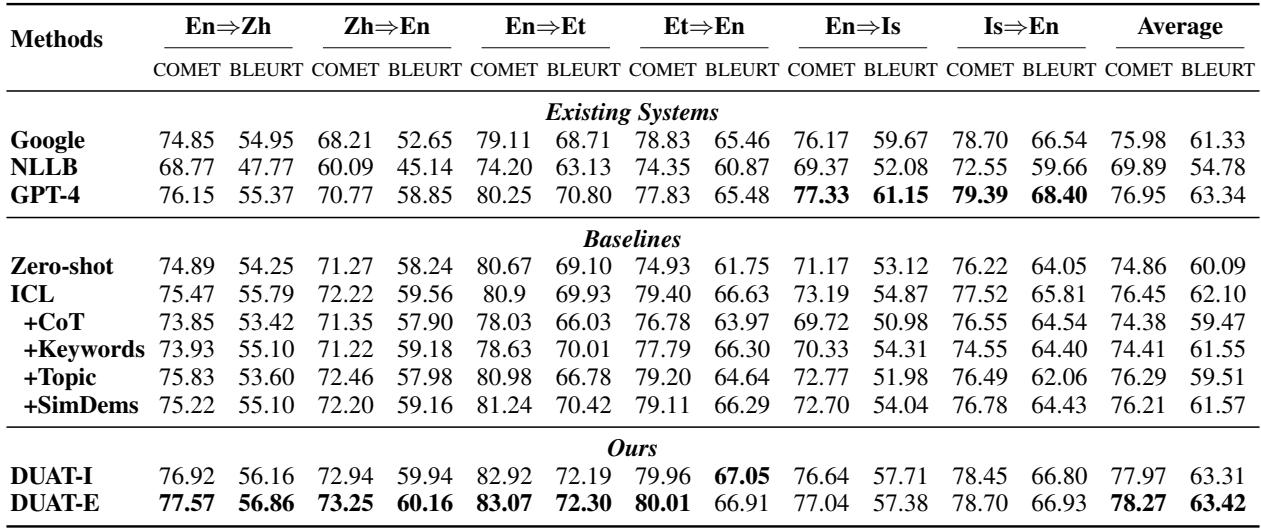

The results on Challenge-WMT were compelling. The researchers compared DUAT against standard Zero-shot translation, Few-shot (ICL), and Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting.

Quantitative Improvements

DUAT outperformed baselines across high-resource (English-Chinese) and low-resource (English-Estonian/Icelandic) pairs.

Notable takeaways from Table 1:

- DUAT-E (External) consistently achieves the highest scores (bolded).

- Chain of Thought (CoT) actually hurt performance in translation tasks (indicated by lower scores than standard ICL). The authors suggest this is because CoT makes the model mimic “junior” translators who are too wordy, whereas DUAT mimics “senior” translators who analyze meaning.

- MAPS (a competing method using keywords) did not perform as well, suggesting that focusing on “difficult words” is more effective than broad keywords.

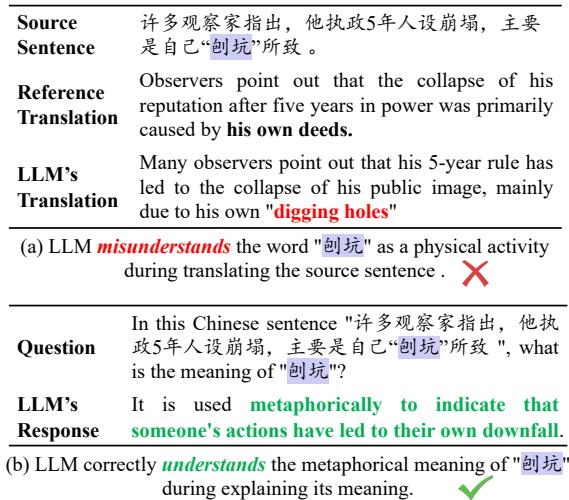

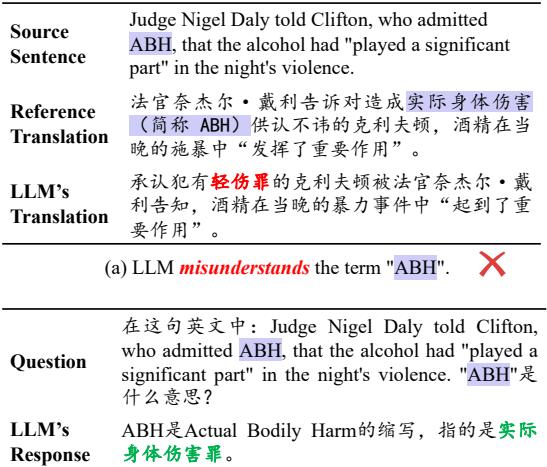

Qualitative Success Stories

The real power of DUAT is best seen in actual examples.

Example 1: Metaphors In the example below, the phrase “digging holes” (刨坑) is a Chinese metaphor for self-sabotage. Standard translation takes it literally (physical digging). DUAT correctly interprets it metaphorically as “someone’s actions have led to their own downfall,” resulting in a correct translation.

Example 2: Terminology In legal contexts, specific acronyms matter. Here, DUAT correctly identifies “ABH” (Actual Bodily Harm) where the baseline failed, ensuring the legal accuracy of the translation.

Human Evaluation

Metrics like COMET and BLEU are useful, but human judgment is the gold standard. Professional translators evaluated the outputs and categorized errors.

Table 4 shows that DUAT significantly reduces Generalization Failures (instances where the model knows the concept but mistranslates it). Furthermore, it reduces Literalness (translating word-for-word), leading to more natural, human-like text.

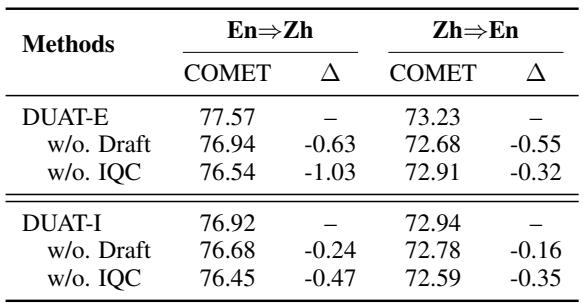

Ablation Study: Do we need all the parts?

You might wonder if the complex “Quality Control” or “Draft Translation” steps are necessary. The ablation study confirms they are.

Removing the Draft Translation (used for detection) or the IQC (Quality Control) leads to performance drops across the board. The IQC is particularly vital; without it, bad interpretations slip through and confuse the model.

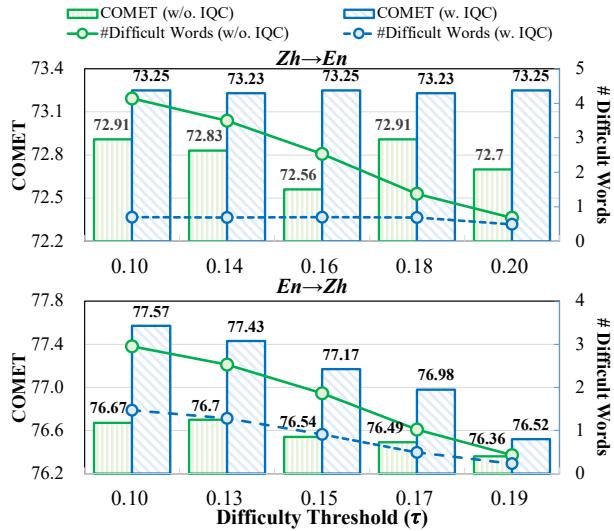

The “Difficulty” Threshold

Finally, the researchers analyzed how sensitive the system should be when detecting difficult words. This is controlled by a threshold parameter \(\tau\) (tau).

The analysis shows a clear trend: using IQC (the blue line) allows the model to interpret more words without losing performance. Without IQC (green line), trying to interpret too many words introduces noise and degrades quality. This proves that filtering interpretations is just as important as generating them.

Conclusion

The DUAT framework highlights a critical insight into Large Language Models: possession of knowledge does not guarantee its application. Just because an LLM “knows” a fact in a Q&A context doesn’t mean it will use that fact during translation.

By explicitly forcing the model to:

- Identify what it finds confusing,

- Interpret those concepts into the target language, and

- Verify those interpretations,

DUAT effectively aligns the model’s deep general understanding with its translation capabilities. It moves machine translation away from simple pattern matching and toward a more cognitive, analytical process resembling human expertise.

For students and researchers in NLP, DUAT serves as a reminder that prompt engineering and pipeline design are about more than just asking the model to “do X.” It is about understanding the model’s internal cognitive dissonance and designing architectures that bridge those gaps.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2401.05072/images/cover.png)