Breaking the Curse: How X-ELM Democratizes Multilingual AI

Imagine trying to pack a suitcase for a trip around the world. You need winter gear for Russia, light linens for Egypt, and rain gear for London. If you only have one suitcase, you eventually run out of space. You have to compromise—maybe you leave the umbrella behind or pack a thinner coat. This is the Curse of Multilinguality.

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), we typically train massive, “dense” multilingual models (like BLOOM or XGLM) that try to learn 100+ languages simultaneously using a single set of parameters. The result? Competition. Languages fight for capacity within the model. Consequently, these multilingual giants often perform worse on a specific language (like Swahili) than a smaller model trained only on that language.

But what if, instead of one giant suitcase, we had a coordinated team of travelers, each carrying specialized gear for a specific region?

This is the premise behind Cross-lingual Expert Language Models (X-ELM). In a fascinating paper from the University of Washington and Charles University, researchers propose a modular approach that breaks the curse of multilinguality, beats standard dense models on equivalent compute budgets, and makes training accessible to smaller research labs.

Background: The Bottleneck of Dense Models

Before dissecting X-ELM, we need to understand the status quo. Standard multilingual Large Language Models (LLMs) are dense. This means that for every token of text processed (whether it’s English, Chinese, or Arabic), the model activates all of its parameters.

This approach has two major downsides:

- Inter-language Competition: As mentioned, high-resource languages (like English) tend to dominate the model’s weights, causing “catastrophic forgetting” or underperformance in low-resource languages.

- Hardware Requirements: Training a dense model requires synchronizing gradients across hundreds of GPUs simultaneously. If you don’t have a supercomputer cluster, you can’t play the game.

To solve this, the authors adapt a technique called Branch-Train-Merge (BTM). The core idea of BTM is simple: instead of training one model on all data, you train several “expert” models independently on different subsets of data and then merge them.

The X-ELM Architecture

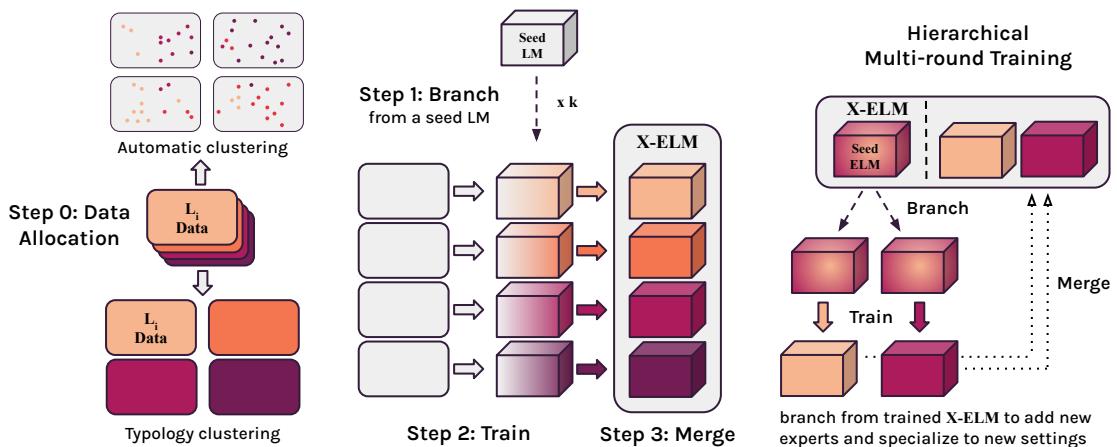

X-ELM extends the BTM paradigm specifically for the multilingual setting. The process involves four key stages: Data Allocation, Branching, Training, and Merging.

1. Data Allocation: Defining the Experts

The first challenge is deciding how to split the multilingual data. If we want to train \(k\) different experts, which expert gets which data? The researchers explored two clustering methods:

A. Balanced TF-IDF Clustering: This uses the statistical properties of the text. Documents are grouped based on word overlap. This is language-agnostic in theory but tends to cluster texts based on vocabulary.

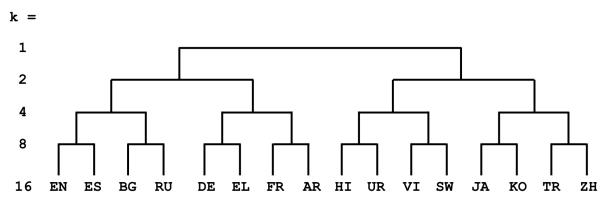

B. Linguistic Typology Clustering (The Winner): This is the linguistically motivated approach. Instead of letting an algorithm blindly sort documents, the researchers used a hierarchical tree based on language similarity. They used the LANG2VEC tool, which measures similarity based on linguistic features (like syntax and phonology).

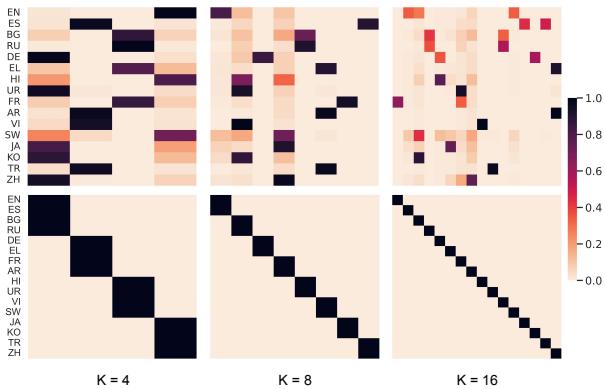

As shown in Figure 2 above, languages are grouped by family. For example, with 4 experts (\(k=4\)), the “Romance” expert might handle French and Spanish, while the “Slavic” expert handles Russian and Bulgarian. This ensures that an expert learns from related languages, allowing for positive transfer (e.g., knowing Spanish helps you model French).

2. Branch, Train, and Merge

Once the data is allocated, the training process is surprisingly efficient:

- Branch: You don’t start from scratch. Each expert is initialized from a “seed” model (in this paper, XGLM-1.7B). This ensures the experts already have a general understanding of language.

- Train: Each expert is trained independently on its assigned data cluster. This is crucial. Because they are independent, Expert A doesn’t need to communicate with Expert B. You can train them on different days, on different hardware, or in different labs. This creates asynchronous training, drastically lowering the barrier to entry.

- Merge: Finally, the experts are collected into a set known as the X-ELM.

3. Inference: Putting the Team to Work

When we want the X-ELM to generate text or answer a question, we have to decide which expert to ask. The paper proposes a few methods:

- Top-1 Expert: We simply pick the expert most specialized for the target language. If we are evaluating German, we use the expert trained on the Germanic cluster.

- Ensembling: We can use all experts at once, weighing their contributions based on how well they fit the input.

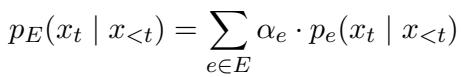

The ensemble probability is calculated using the following equation:

Here, \(\alpha_e\) represents the weight of a specific expert. If the input looks like Spanish, the Spanish-trained expert gets a high \(\alpha\) (weight), and the Chinese-trained expert gets a low weight.

Experiments: Does it Work?

The researchers tested X-ELM across 16 languages using the mC4 dataset. They controlled the experiment by ensuring the compute budget (total number of tokens seen) was identical between the X-ELM ensemble and the dense baseline.

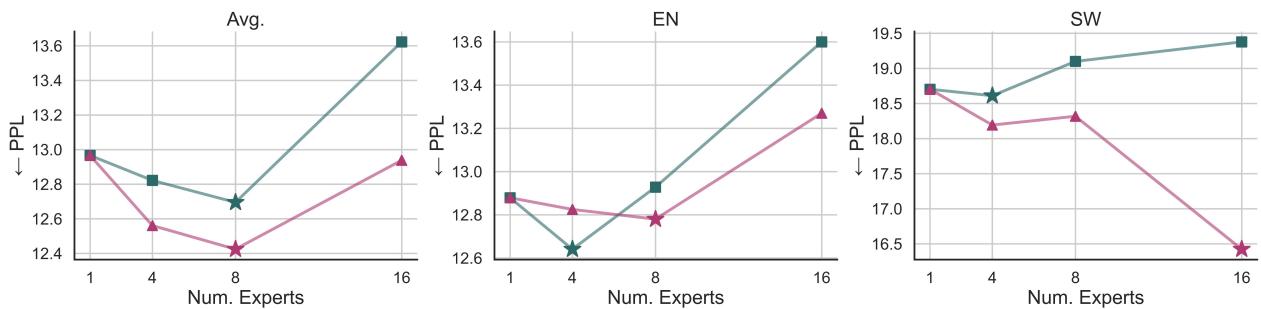

Finding the Sweet Spot (\(k\))

Is it better to have 16 monolingual experts (one for each language) or fewer experts that share languages?

Figure 3 reveals an interesting “Goldilocks” zone.

- Left (Avg): The average perplexity (lower is better) is lowest at \(k=8\) experts.

- Right (SW - Swahili): While Swahili prefers a dedicated expert (\(k=16\)), most languages benefit from sharing parameters with related languages (\(k=8\)).

Notably, the Typology clustering (triangles) consistently outperforms the TF-IDF clustering (squares). This confirms that grouping languages by linguistic family is more effective than grouping them by raw vocabulary statistics.

Performance Gains

The results were definitive. When given the same compute budget:

- X-ELM outperforms the dense baseline across all 16 considered languages.

- Typology matters: Monolingual experts (\(k=16\)) generally underperformed the typologically clustered experts (\(k=8\)). This suggests that “Linguistically Targeted Multilinguality” is superior to pure monolingual training.

Fairness for Low-Resource Languages

A common criticism of multilingual models is that they favor English and leave low-resource languages behind. Does X-ELM solve this?

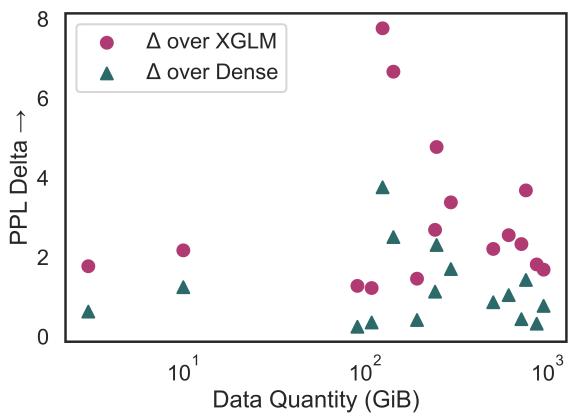

Figure 4 plots the improvement (Delta PPL) against the amount of available data.

- The Teal Triangles show improvement over the dense baseline.

- The trend is relatively flat or slightly negative, meaning X-ELM provides substantial gains for both high-resource and low-resource languages. It does not disproportionately favor the rich.

Downstream Tasks (In-Context Learning)

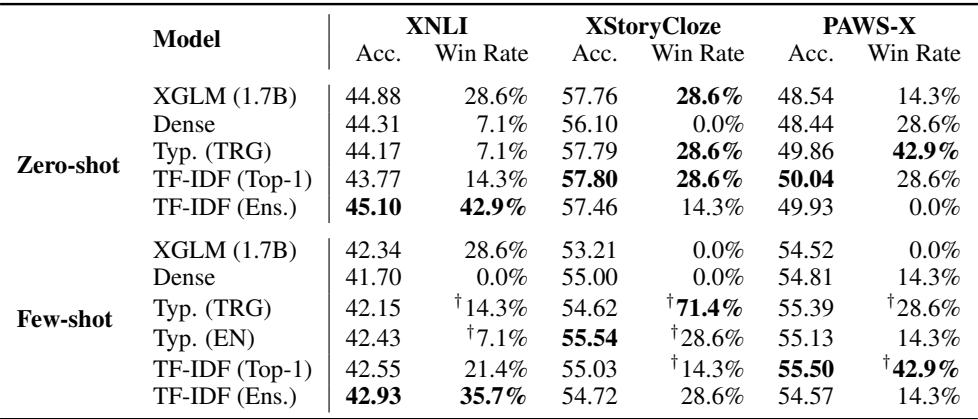

Perplexity (how well a model predicts the next word) doesn’t always translate to task performance. To verify their findings, the authors evaluated X-ELM on tasks like XNLI (Natural Language Inference) and XStoryCloze.

As shown in Table 3, the X-ELM (Typological) models achieve higher accuracy and “Win Rates” compared to the dense baselines in both zero-shot and few-shot settings. This confirms that the improved language modeling capabilities translate to better reasoning and understanding.

HMR: Adapting to New Languages

Perhaps the most exciting contribution of this paper is Hierarchical Multi-Round (HMR) training.

Standard dense models are hard to update. If you want to add Azerbaijani to a model trained on English and Russian, you usually have to continue training the whole massive model, risking “catastrophic forgetting” where the model forgets English to learn Azerbaijani.

With X-ELM and HMR, you use the linguistic tree (from Figure 2) to your advantage.

- Identify a Donor language (e.g., Turkish is linguistically similar to Azerbaijani).

- Take the expert trained on the Turkish cluster.

- Branch off a copy of that expert.

- Train the new copy on Azerbaijani.

The researchers tested this on four unseen languages: Azerbaijani, Hebrew, Polish, and Swedish.

The Result: HMR outperformed standard Language Adaptive Pretraining (LAPT). By branching from a related expert, the model learned the new language faster and more effectively, without degrading the performance of the original experts.

Analysis: Data Distribution and Forgetting

To understand why X-ELM works, we can look at how the data is distributed and what the experts actually remember.

Figure 5 visualizes the data split. The bottom row (Typology) shows clean, hard assignments—each language goes to one expert. The top row (TF-IDF) shows a messier distribution. The clean separation of the Typological approach minimizes negative interference between distant languages (e.g., Chinese and English don’t fight for space in the same expert).

However, specialization comes at a cost: Forgetting.

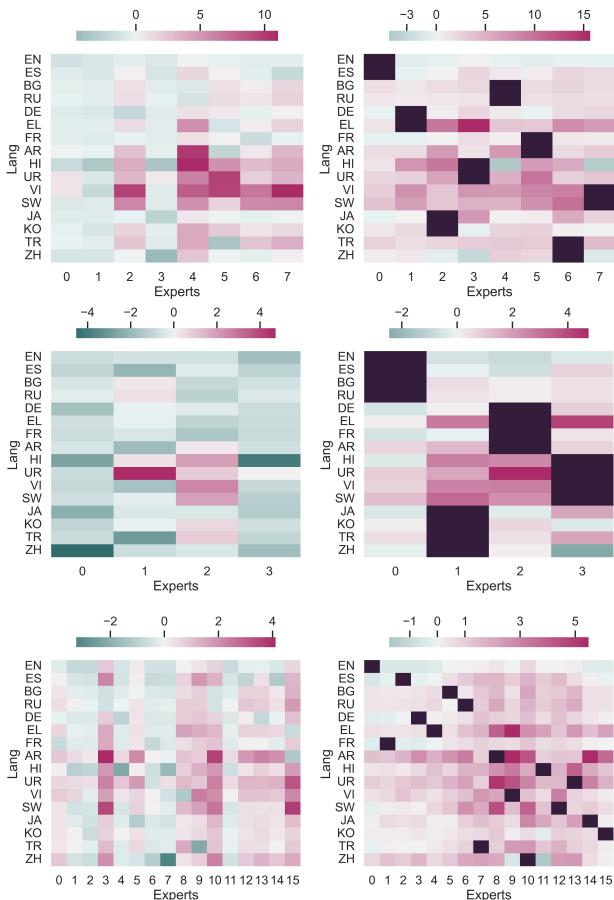

In Figure 6, the darker red areas indicate languages the expert has “forgotten” (perplexity increased compared to the seed).

- Right Side (Typology): You see distinct blocks. The expert specialized in European languages forgets Asian languages, and vice versa.

- This is a feature, not a bug. Because we ensemble the experts at inference time, it doesn’t matter if the “Asian Expert” forgets French. The “European Expert” remembers it. This efficient “forgetting” allows each expert to maximize its capacity for its assigned languages.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Curse of Multilinguality” has long suggested that we have to choose between a massive, expensive model that is mediocre at everything, or many specific models that can’t talk to each other. X-ELM proves there is a third way.

By combining Branch-Train-Merge with Linguistic Typology, X-ELM offers:

- Better Performance: Beats dense models on the same budget.

- Efficiency: Allows for asynchronous training (no need for massive GPU clusters).

- Flexibility: New languages can be added via HMR without retraining the whole system.

This approach democratizes multilingual NLP. It allows smaller research groups to contribute “experts” to a larger ensemble, gradually building a more capable global system. Instead of one heavy suitcase, we can now carry a perfectly organized set of specialized luggage, ready for any language the world speaks.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2401.10440/images/cover.png)