Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with information. However, they suffer from a well-known flaw: hallucination. When asked about specific, factual data—like the number of citations a researcher has or the specific rail network of a small town—LLMs often guess convincingly rather than answering accurately.

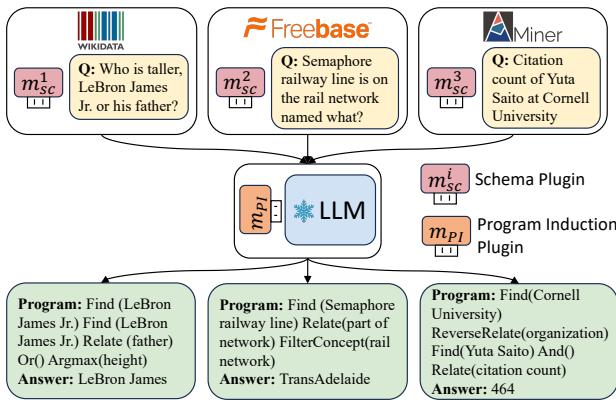

To solve this, researchers link LLMs to external Knowledge Bases (KBs). Instead of answering directly, the LLM acts as a translator. It converts a natural language question (e.g., “Who is taller, LeBron James Jr. or his father?”) into a logical program (e.g., Find(LeBron James Jr.) -> Relate(Father) -> ...). This process is called Program Induction (PI).

But there is a catch. To teach an LLM to write programs for a specific KB (like Freebase or a private company database), you typically need thousands of training examples (question-program pairs). For “low-resourced” KBs—custom databases or specific domains like movies or academia—this data simply doesn’t exist.

How do we bridge this gap? How can we teach an LLM to query a database it has never seen before, without needing expensive annotated data?

Enter KB-Plugin. In a recent paper, researchers proposed a modular framework that separates the “skill” of reasoning from the “knowledge” of a specific database schema. By using lightweight, pluggable modules, KB-Plugin allows an LLM to master new KBs instantly. This article breaks down how this framework works, why it outperforms models 25 times its size, and what it means for the future of structured reasoning.

The Problem: The High Cost of Adaptation

Imagine you are a software engineer who knows Python perfectly. If you join a new company, you don’t need to relearn Python; you just need to learn the company’s specific codebase and variable names.

Existing methods for Program Induction generally fail to make this distinction. They retrain the whole model (or a large part of it) for every new KB. If you want to query a Movie KB, you train on movie questions. If you switch to an Academic KB, you start over. This requires massive annotated datasets for every single domain, which is impractical for most real-world applications.

The researchers identified that the main challenge isn’t the logic—LLMs already understand concepts like “filter” or “relate”—but the schema alignment. The model struggles to map the words “plays for” in a question to the specific relation ID basketball_team.roster.player in the database.

The Solution: KB-Plugin

The core idea behind KB-Plugin is modularity. The framework assumes that the parameters of an LLM can encode task-specific knowledge. Therefore, we should be able to inject specific knowledge using Pluggable Modules (specifically Low-Rank Adaptation, or LoRA).

KB-Plugin splits the problem into two distinct plugins:

- Schema Plugin (KB-Specific): This module acts as a “dictionary” for a specific Knowledge Base. It encodes the detailed schema information (relations, concepts, and structure).

- PI Plugin (Transferable): This module acts as the “reasoner.” It learns the general skill of converting questions into programs by looking up information in the Schema Plugin.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the architecture is elegant. You have a central LLM (frozen). When a question comes in for Wikidata, you plug in the Wikidata Schema Plugin. When a question comes in for a custom Miner KB, you swap it for the Miner Schema Plugin. The PI Plugin remains constant, handling the logic for everyone.

Mathematically, the final model for a target Knowledge Base (\(T\)) looks like this:

Here, \(M\) is the base LLM, \(m_{sc}^T\) is the schema plugin for the target, and \(m_{PI}\) is the transferable reasoning plugin.

Core Method: How It Works

The brilliance of KB-Plugin lies in how these two modules are trained. The researchers had to solve two problems:

- How do you train a Schema Plugin without Q&A data?

- How do you train a PI Plugin to be “generic” and not memorize a specific database?

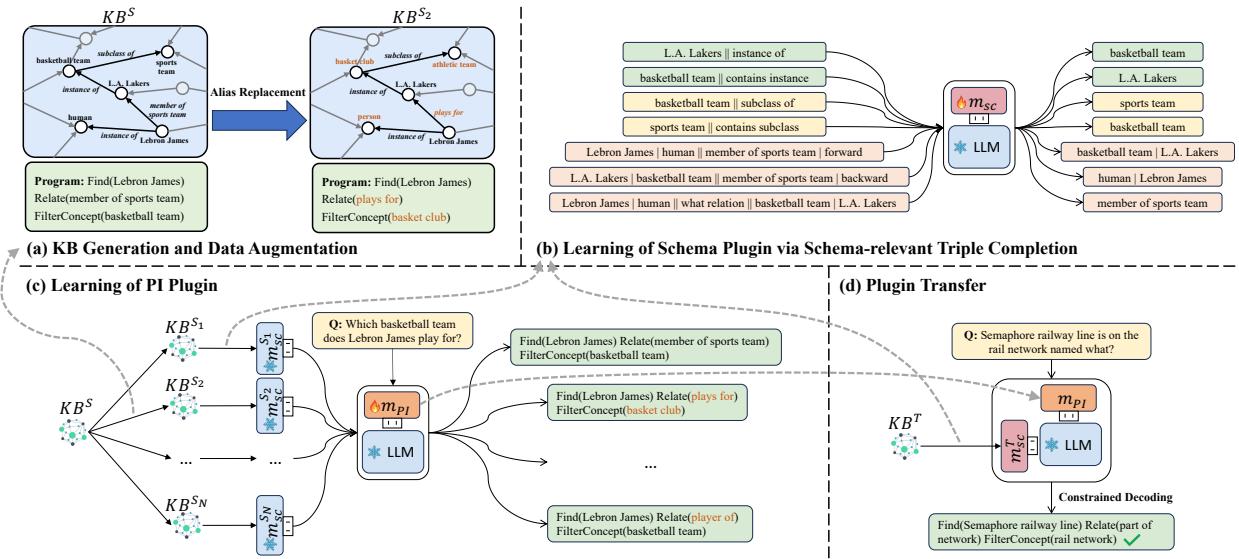

The framework utilizes a four-step process, visualized below:

Let’s break down these distinct stages.

1. The Architecture: LoRA

Before diving into the training steps, it is important to understand the tool being used. The plugins are implemented using LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation). Instead of updating all the weights in the massive LLM, LoRA injects small, trainable rank decomposition matrices into the distinct layers of the model.

This allows the “Schema Plugin” to be tiny (around 40MB) while effectively modifying the LLM’s behavior to understand a specific dataset.

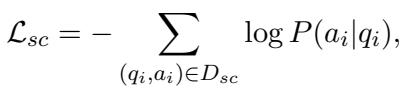

2. Learning the Schema Plugin (Self-Supervised)

The researchers needed a way to teach the plugin about a KB’s structure using only the data inside the KB itself. They devised a Self-Supervised Triple Completion Task.

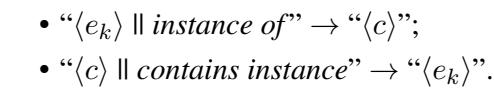

The model is given a fact from the database and asked to complete it. This forces the plugin to memorize the relationships between concepts and entities.

For example, to learn about a “Concept” (like City or Airport), the model is trained on “instance of” triples:

Here, the model sees an entity and must predict its concept, or sees a concept and predicts an entity.

To learn about “Relations” (like flight_to or born_in), the system constructs more complex queries involving forward and backward reasoning:

The objective function maximizes the likelihood of predicting the correct schema items:

By training on thousands of these auto-generated examples, the Schema Plugin effectively “downloads” the entire database structure into its parameters. It learns that “Rome” is connected to “Italy” via “Capital Of,” without ever seeing a human-written question.

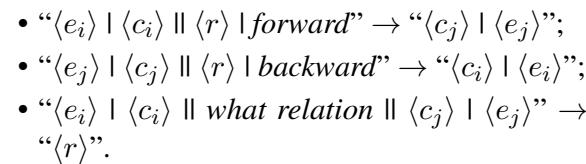

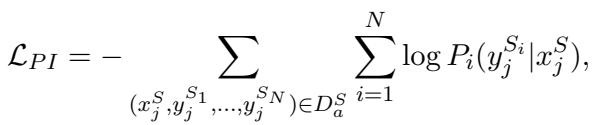

3. Learning the PI Plugin (The General Reasoner)

Now we need a driver who knows how to read this map. We have a rich source dataset (e.g., Wikidata) with many questions and programs. However, if we just train the PI Plugin on Wikidata, it will memorize Wikidata’s specific relation names and fail when moved to a new database.

To prevent memorization, the researchers used Data Augmentation via Alias Replacement.

They took the Source KB and generated multiple “fake” KBs (\(S_1, S_2, \dots S_N\)). In each variant, they randomly renamed relations and concepts using aliases (e.g., changing “basketball team” to “basket club” or “hoops squad”).

The PI Plugin is then trained to answer the same questions across these different schema variants.

Because the schema names keep changing, the PI Plugin cannot memorize them. Instead, it is forced to learn a higher-level skill: “Look at the question, look at the current Schema Plugin, and extract the matching relation.” This is the key to transferability.

4. Zero-Shot Transfer

Finally, to handle a new, low-resource Target KB (\(T\)):

- Train a Schema Plugin for \(T\) (using the self-supervised method from Step 2).

- Plug it into the LLM along with the pre-trained PI Plugin.

- The model can now answer questions over KB \(T\), even though the PI Plugin has never seen it before.

Experiments and Results

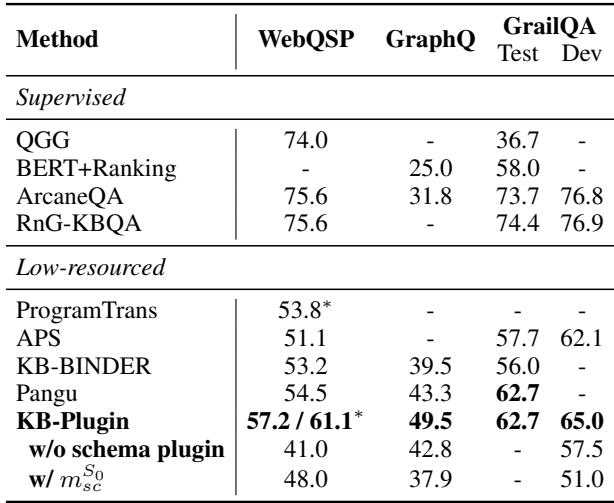

The researchers tested KB-Plugin using Llama2-7B as the backbone. They used KQA Pro (Wikidata) as the rich source dataset and tested on five different low-resource datasets, including WebQSP and GraphQ (Freebase), MetaQA (Movies), and SoAyBench (Academic).

Main Performance

The results were impressive. KB-Plugin was compared against Pangu and KB-BINDER, state-of-the-art methods that use huge models like Codex (175B parameters).

As shown in Table 2, KB-Plugin (using only a 7B model) achieved better or comparable performance to Pangu (175B). On the GraphQ dataset, it improved F1 scores by over 6%, and on WebQSP by nearly 3%. This is a massive efficiency gain—achieving SOTA results with a model 25 times smaller.

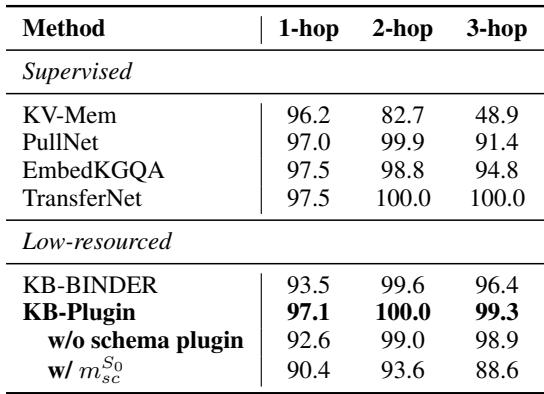

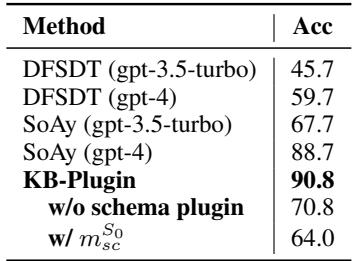

Domain-Specific Transfer

The framework proved highly effective not just on general knowledge (Freebase) but also on specific domains.

In the academic domain (SoAyBench, Table 4), KB-Plugin reached 90.8% accuracy, outperforming GPT-4 based methods. This highlights the power of the Schema Plugin: GPT-4 has general knowledge, but KB-Plugin has precise, injected knowledge of the specific academic database structure.

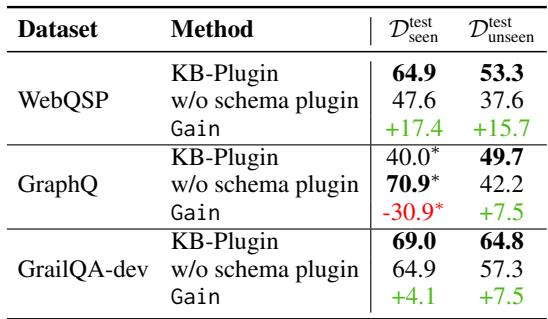

Why the Schema Plugin Matters

You might ask: “Do we really need the Schema Plugin? Can’t the PI Plugin just figure it out?” The researchers ran an ablation study to find out.

Table 5 shows a stark drop in performance when the Schema Plugin is removed, especially for “unseen” test cases (questions involving relations that weren’t in the training data). On GraphQ, the performance on unseen data dropped by 7.5 points, and on WebQSP by nearly 16 points. The Schema Plugin is essentially the bridge that allows the model to “understand” relations it hasn’t explicitly been taught to use.

The Effect of Synthetic KBs

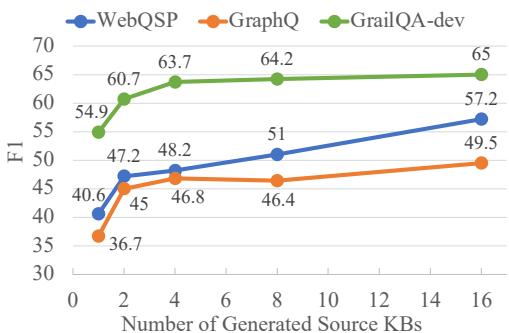

Finally, the researchers validated their data augmentation strategy. Does creating those “fake” source KBs actually help?

Figure 3 confirms that training with just one source KB results in poor transfer (the model memorizes). As the number of generated source KBs increases (from 1 to 16), the F1 score climbs steadily. This proves that exposing the PI Plugin to shifting schemas during training is crucial for learning true transferability.

Conclusion and Implications

KB-Plugin represents a significant shift in how we approach Knowledge Base Question Answering (KBQA). Rather than treating LLMs as static repositories of facts or requiring massive fine-tuning for every new task, this framework treats them as modular engines.

Key Takeaways:

- Decoupling works: Separating “Schema Knowledge” from “Reasoning Skill” allows for flexible, plug-and-play AI.

- Size isn’t everything: A 7B parameter model with the right modular architecture can outperform a 175B parameter generalist model.

- Data scarcity is solvable: By using self-supervised learning for the schema and synthetic data augmentation for the reasoning, we can tackle low-resource domains effectively.

For students and developers, this implies a future where adapting an LLM to a private company database or a niche scientific archive doesn’t require thousands of hours of data labeling. You simply plug in the schema, and let the model do the rest.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.01619/images/cover.png)