We have all been there. You ask ChatGPT or Claude a specific question about a historical event or a niche scientific concept. The answer flows out elegantly, formatted perfectly, and sounds completely authoritative. But then you double-check a date or a name, and you realize: the model made it up.

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we search, extract, and integrate information. They free us from having to open twenty tabs to find a simple answer. However, their utility is severely capped by one major flaw: factuality.

In the research paper “Factuality of Large Language Models: A Survey,” researchers from MBZUAI, Monash University, Google, and others provide a comprehensive overview of why LLMs fail to tell the truth, how we measure those failures, and the cutting-edge methods being used to fix them.

This article breaks down their survey into a cohesive narrative, designed to help students understand the current landscape of LLM factuality.

The Core Problem: Fluency vs. Truth

The first hurdle in understanding LLM errors is terminology. In the AI community, you will often hear two terms thrown around: Hallucination and Factuality. While they overlap, the authors argue that distinguishing them is vital for solving the problem.

Hallucination vs. Factuality

In traditional Natural Language Processing (NLP), “hallucination” meant the generated text didn’t match the source text (like a summary including details not present in the original article).

In the era of LLMs, the definition has blurred. The authors propose a cleaner distinction:

- Hallucination: This happens when an LLM generates content that is nonsensical or unfaithful to the provided source. A model can hallucinate by going off-topic or adding “fluff” that wasn’t asked for, even if that fluff is technically true.

- Factuality Error: This is a discrepancy between the generated content and verifiable real-world facts. This manifests as factual inconsistency (contradicting known reality) or fabrication (inventing things that don’t exist).

Key Takeaway: A model can be factually correct but still hallucinate (by being unfaithful to the prompt). Conversely, a model can be faithful to a prompt (if the prompt contains lies) but factually incorrect.

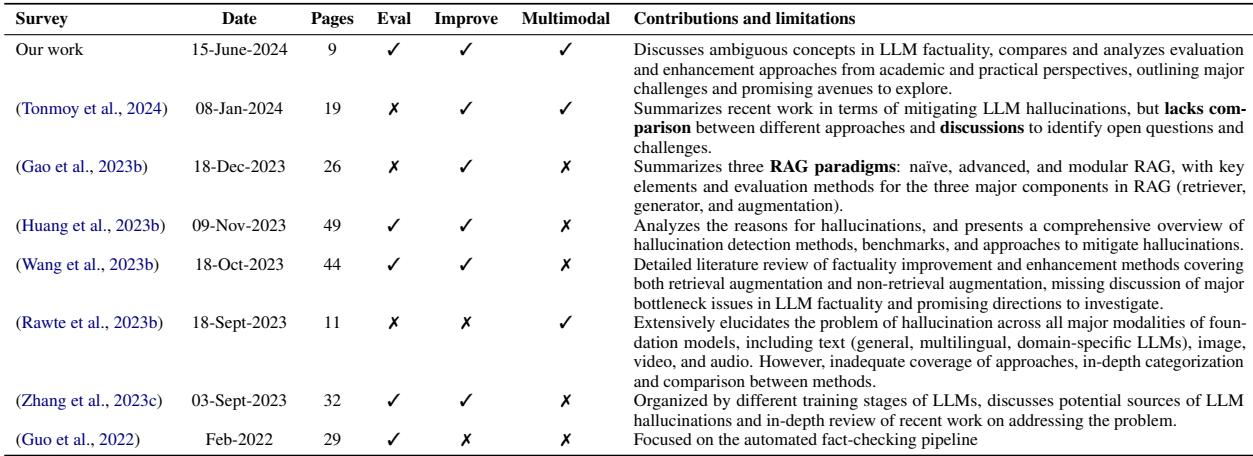

To understand where this specific survey fits into the broader academic conversation, the authors provided a comparison of existing literature.

As shown in Table 1, while other surveys focus heavily on specific mitigation techniques like Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), this paper aims to cover the entire lifecycle: from evaluation to improvement across training stages, including the often-overlooked area of multimodal (image/text) factuality.

Evaluating Factuality: How Do We Grade Truth?

If you want to improve a model’s factuality, you first need a way to measure it. This is harder than it sounds. If an LLM writes a biography of a scientist, there isn’t a single “gold standard” sentence to compare it against. The biography could be written in a thousand different ways and still be accurate.

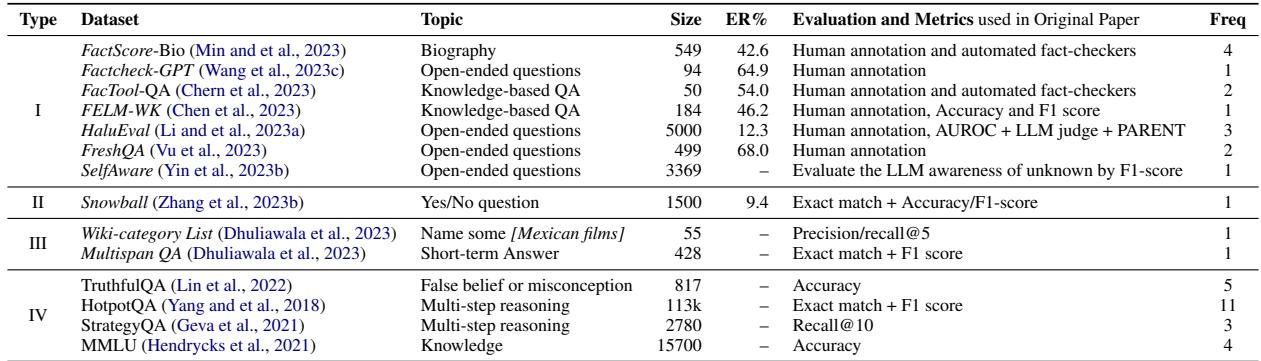

The researchers categorize evaluation datasets into four distinct types, ranging from easy-to-automate to extremely difficult.

Type I: Open-Ended Generation (The Hardest)

This represents the real-world use case: “Tell me about the early life of Marie Curie.”

- The Challenge: The output is long, free-form text. There are no A/B/C/D labels.

- Evaluation: This usually requires human experts or complex “Automatic Fact-Checkers” (more on this later).

- Example Datasets: FactScore-Bio, Factcheck-GPT.

Type II: Yes/No Questions

- The Challenge: Simpler, but prone to guessing.

- Evaluation: Binary classification metrics (Accuracy, F1-score).

- Example Datasets: Snowball.

Type III: Short-Form Answers

- The Challenge: The model must produce a specific entity (e.g., a name or date) or a list.

- Evaluation: Exact match or Recall@K (did the correct answer appear in the top K suggestions?).

- Example Datasets: Wiki-category List.

Type IV: Multiple Choice (The Easiest)

- The Challenge: Standardized testing.

- Evaluation: High automation. We can easily calculate accuracy.

- Example Datasets: MMLU, TruthfulQA.

While Type IV is easy to run, Type I is where the industry is heading. We don’t just want LLMs to pass multiple-choice tests; we want them to write reliable reports. This pushes the need for better Automatic Fact-Checkers.

The Anatomy of an Automatic Fact-Checker

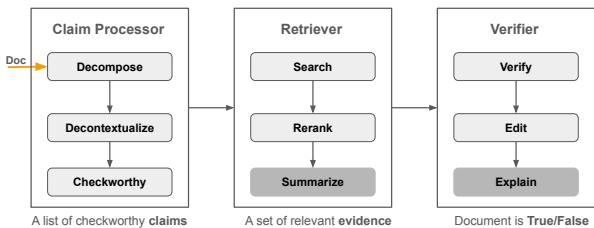

Because humans can’t read millions of LLM outputs to check for accuracy, we are building AI systems to check other AI systems. The authors describe a standard framework for these automated pipelines.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the pipeline consists of three critical stages:

Claim Processor (Decompose & Detect): The system takes a long document generated by an LLM and breaks it down into “atomic claims.” For example, the sentence “Obama was born in Hawaii in 1961” might be split into two claims: “Obama was born in Hawaii” and “Obama was born in 1961.” It then filters for “check-worthy” claims (ignoring opinions or greetings).

Retriever (Search): The system queries a knowledge base (like Wikipedia or the open web) to find evidence relevant to those atomic claims. It reranks the search results to find the most pertinent information.

Verifier (Judge): Using the retrieved evidence, the system (often another LLM) determines if the claim is

True,False, orNot Enough Info. Some advanced systems, like Factcheck-GPT, even offer an “Edit” step to fix the error.

The Bottleneck: The main limitation here is the “chicken and egg” problem. If we use GPT-4 to verify the factuality of ChatGPT, we are relying on the factuality of GPT-4. If the verifier hallucinates, the evaluation is flawed.

Methods for Improving Factuality

Once we know a model is lying, how do we fix it? The survey breaks down solutions based on the lifecycle of the LLM: Pre-training, Tuning, and Inference.

1. Pre-training: “Garbage In, Garbage Out”

The most fundamental way to improve factuality is to ensure the model reads high-quality text during its initial training.

- Data Filtering: Researchers are moving away from blindly scraping the web. Techniques now involve filtering datasets to prioritize reliable sources (like textbooks or Wikipedia) over random forums.

- Retrieval-Augmented Pre-training: Models like RETRO are trained from scratch with a built-in search engine. They don’t just memorize text; they learn to look up tokens from a database during the learning process.

2. Tuning: Teaching the Model to Behave

After pre-training, models undergo Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) and Reinforcement Learning (RLHF).

- Knowledge Injection: You can fine-tune a model on specific knowledge graphs or entity summaries to update its internal database.

- Refusal-Awareness: One of the biggest causes of hallucination is the model trying to be helpful when it doesn’t know the answer. R-tuning teaches models to say “I don’t know” rather than making up a plausible-sounding lie.

- The Sycophancy Problem: Models are often tuned to please humans. If a user asks a question with a false premise (e.g., “Why is the earth flat?”), an eager model might hallucinate an answer to satisfy the user. New tuning methods use synthetic data to teach models that truthfulness matters more than user approval.

3. Inference: Better Decoding Strategies

Even a well-trained model can hallucinate if you use the wrong settings when generating text.

- Decoding Strategies: The standard “nucleus sampling” (picking the next word based on probability) introduces randomness to make text creative. However, randomness kills factuality. New methods like Factual-Nucleus Sampling dynamically reduce randomness as the sentence gets longer.

- DoLa (Decoding by Contrasting Layers): This is a fascinating technique where the model contrasts the output of its mature (later) layers against its premature (earlier) layers. The theory is that factual knowledge resides in specific layers, and by amplifying those signals, we can cut out the noise.

- In-Context Learning (ICL): Simply providing “demonstration examples” in the prompt can help. If you show the model examples of how to verify facts or how to admit ignorance, it performs better via imitation.

The Role of Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

Perhaps the most popular method in the industry right now is RAG. The survey treats this as a cross-cutting solution that applies to all stages.

In a RAG system, the LLM is connected to an external database. When you ask a question, it retrieves relevant documents and uses them to generate the answer.

- Pre-generation RAG: The model gets the documents before it starts writing. This constrains the output space, making it stick to the facts found in the documents.

- Snowballing: A major risk identified in the paper is “hallucination snowballing.” If an LLM makes one small error early in a sentence, it will often double down on that error in subsequent sentences to maintain consistency. RAG can help, but if the retrieved document is biased or if the model misinterprets it, the snowball effect can still occur.

Multimodal Factuality: When Eyes Deceive

The survey extends beyond text to discuss Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs)—models that can see and talk (like GPT-4V). Factuality errors here are different:

- Existence Factuality: Claiming an object is in the image when it isn’t.

- Attribute Factuality: Getting the color, shape, or size wrong.

- Relationship Factuality: Misunderstanding how objects interact (e.g., saying a cup is on the table when it is hovering above it).

Improving this involves “Instruction Tuning” with negative examples—specifically training the model on what not to say about an image.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The paper concludes that while we have made massive strides, three major challenges remain:

- LLMs are probabilistic, not logical. They are trained to predict the next word, not to verify truth. Changing this fundamental objective is difficult.

- Evaluation is messy. We lack a unified, automated framework that everyone agrees on. We are still relying too much on costly human evaluation or imperfect AI-based judges.

- Latency. Real-time fact-checking and retrieval take time. A user chatting with a bot expects an instant reply, but a rigorous fact-check loop might take seconds or minutes.

The future of LLM factuality likely lies in calibration—making models aware of their own limitations so they can confidently state what they know and humbly admit what they don’t. Until then, techniques like RAG and automated fact-checking pipelines remain our best defense against the confident hallucinations of our digital assistants.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.02420/images/cover.png)