Introduction

In the world of Artificial Intelligence, Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are the unsung heroes. They power the sidebar on your Google Search, drive product recommendations on Amazon, and help complex systems understand that “Paris” is the capital of “France.” To make these graphs useful for machine learning, we use Knowledge Graph Embedding (KGE) models. These models translate entities (like “Paris”) and relations (like “is capital of”) into mathematical vectors and matrices.

For years, models like TransE and RotatE have been the gold standard. They are efficient and generally effective. However, a recent research paper has uncovered a fundamental logical flaw buried deep within the mathematics of these popular models. The researchers call it the “Z-paradox.”

Imagine a scenario: You act in a movie. Your friend acts in that same movie. Your friend also acts in a different movie. Does that automatically mean you acted in that second movie? Obviously not. But surprisingly, many state-of-the-art AI models mathematically force this connection to be true. They hallucinate a relationship simply because the structure of the data looks like the letter “Z”.

In this post, we are going to dive deep into the paper “MQuinE: a cure for Z-paradox in knowledge graph embedding models.” We will explore what the Z-paradox is, prove why existing models fail, and examine the solution: a new model called MQuinE (Matrix Quintuple Embedding) that uses a clever matrix architecture to cure this deficiency without losing expressiveness.

Background: The State of Knowledge Graph Embeddings

Before tackling the paradox, we need to understand how machines “read” knowledge graphs. A knowledge graph is a collection of facts represented as triplets: (Head, Relation, Tail), or \((h, r, t)\). For example: (Leonardo DiCaprio, ActedIn, Inception).

The goal of a KGE model is to learn a scoring function, \(s(h, r, t)\). If the triplet is a true fact, the score should be low (or high, depending on the convention; in this paper, lower is better, closer to 0). If the fact is false, the score should be high.

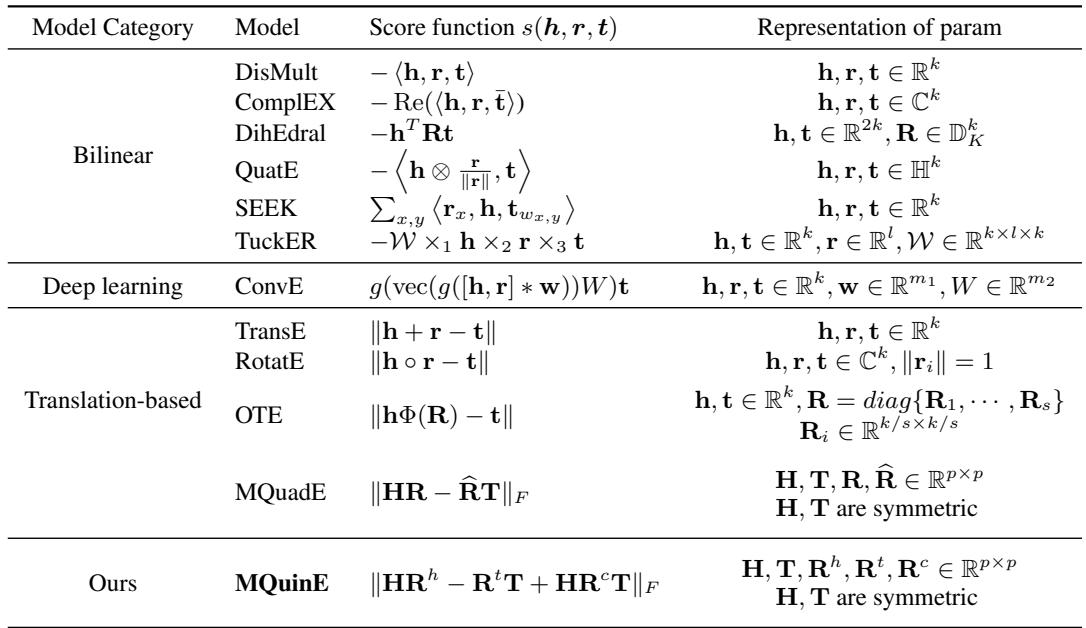

Over the last decade, researchers have developed various “geometric” ways to represent these relations.

- Translation-based models (e.g., TransE): These treat relations as a vector translation. If you take the vector for “King” and add the vector for “Woman”, you should get close to the vector for “Queen”. Mathematically: \(\mathbf{h} + \mathbf{r} \approx \mathbf{t}\).

- Rotation-based models (e.g., RotatE): These treat relations as rotations in a complex vector space.

- Bilinear models: These use matrix multiplication to capture interactions.

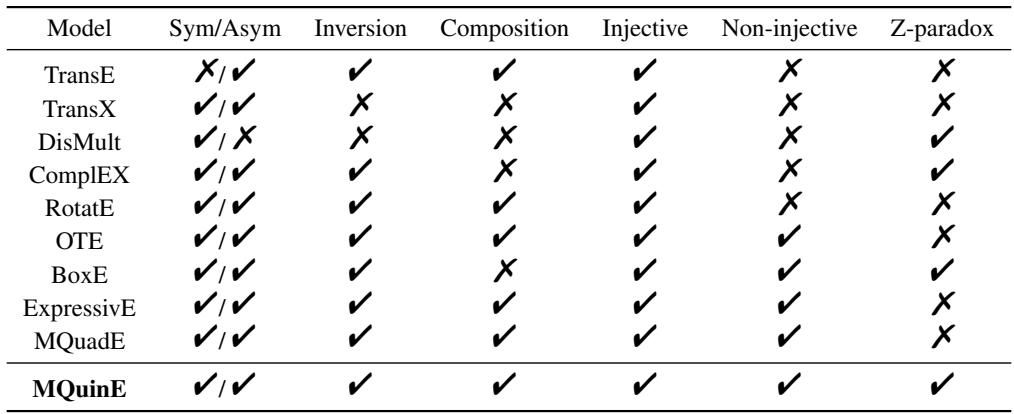

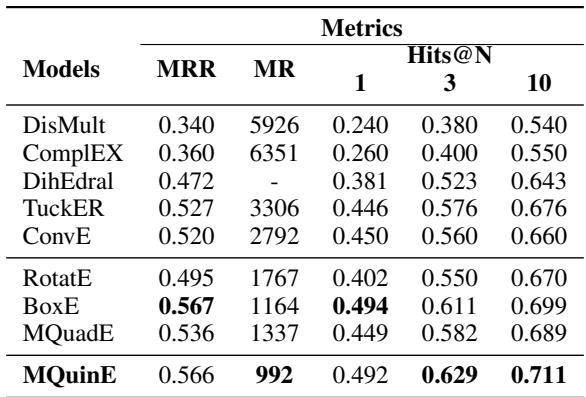

As shown in the table above, the field has evolved from simple distance functions to complex tensor factorizations. However, expressiveness—the ability to model different logical patterns like symmetry or hierarchies—is the main battleground. The authors of MQuinE argue that despite this progress, a specific logical trap has been overlooked.

The Problem: The Z-Paradox

The core contribution of this paper is the identification of the Z-paradox. This is a situation where a model lacks the “expressiveness” to distinguish between two different logical possibilities.

Visualizing the Paradox

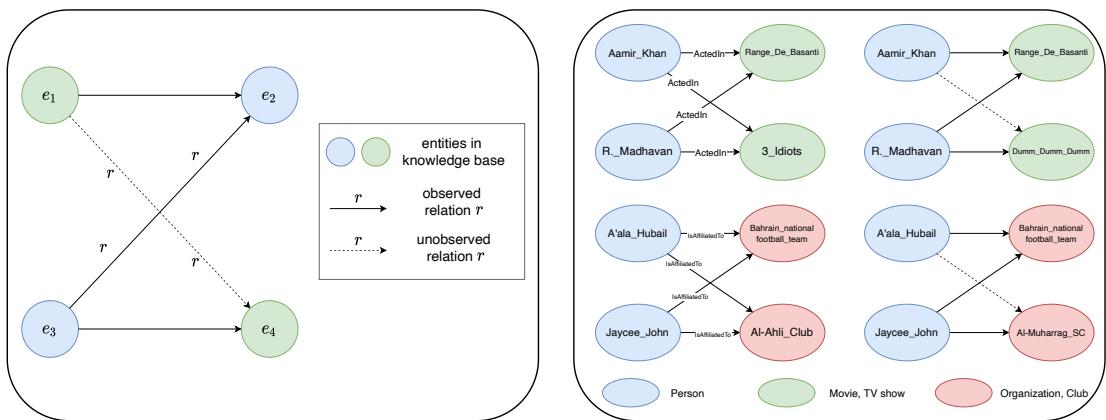

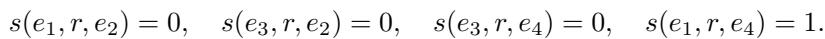

Let’s look at the structure that causes the problem. We have four entities (\(e_1, e_2, e_3, e_4\)) and one relation \(r\).

- \(e_1\) is related to \(e_2\).

- \(e_3\) is also related to \(e_2\).

- \(e_3\) is related to \(e_4\).

The question is: Is \(e_1\) related to \(e_4\)?

In the real world, the answer is “maybe” or “not necessarily.” However, the authors discovered that for translation-based models, the answer is mathematically forced to be “yes.”

The image above illustrates this perfectly.

- Left Panel: This shows the Z-structure. The solid arrows are known facts. The dashed arrow (\(e_3 \to e_4\)) is also known. The Z-paradox is that the model infers the connection between \(e_1\) and \(e_4\) (the bottom dashed line) even if it shouldn’t exist.

- Right Panel: A real-world example from the YAGO3 dataset.

- Top Left: Aamir Khan acted in Range De Basanti. R. Madhavan acted in Range De Basanti and 3 Idiots. The model infers Aamir Khan acted in 3 Idiots. In this specific case, it happens to be true.

- Top Right: Aamir Khan acted in Range De Basanti. R. Madhavan acted in Range De Basanti and Dumm Dumm. The model infers Aamir Khan acted in Dumm Dumm. This is false. But the model cannot help itself; the math forces the connection.

The Mathematical Proof of Failure

Why does this happen? It comes down to the score functions used by models like TransE and RotatE. These models rely on measuring the distance between transformed embeddings.

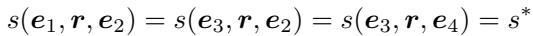

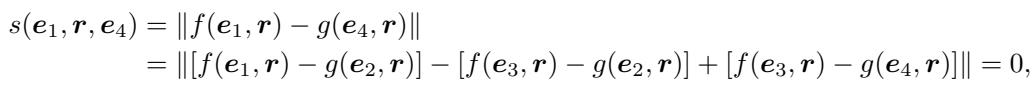

The authors formally define the paradox as follows:

If the scores for the three “legs” of the Z-shape are equal to the optimal score \(s^*\) (usually 0), and this implies that the score for the fourth leg (\(e_1 \to e_4\)) must also be \(s^*\), then the model suffers from Z-paradox.

Let’s prove why translation models fail. Most translation models define a score function \(s(h,r,t)\) that can be separated into a function of the head and a function of the tail: \(\|f(h,r) - g(t,r)\|\). Ideally, for a true fact, this distance is 0, meaning \(f(h,r) = g(t,r)\).

If we have the three facts from our Z-structure, we have these equalities:

Now, look at what happens when we try to calculate the score for the unobserved triplet \((e_1, r, e_4)\):

Because of the linear nature of the distance function, the terms cancel out perfectly. The score becomes 0. The model is mathematically incapable of predicting anything other than “True” for this relationship. It doesn’t matter how much data you train on; the architecture itself is the limitation.

This isn’t just a problem for simple models. The authors point out that even sophisticated bilinear models (like DisMult or ComplEx) can suffer from this if they are set up in certain ways (e.g., using orthogonal matrices).

The Solution: MQuinE

To fix this, the researchers propose MQuinE (Matrix Quintuple Embedding). The name comes from the fact that it uses five matrices to represent the entities and relations involved in a triplet.

The goal was to design a scoring function that:

- Breaks the linear dependency that causes the Z-paradox.

- Retains the ability to model complex patterns (symmetry, inversion, hierarchies).

The Architecture

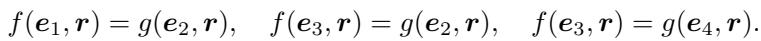

In MQuinE:

- Entities (\(h, t\)): Are represented by symmetric matrices \(\mathbf{H}\) and \(\mathbf{T}\).

- Relations (\(r\)): Are represented by a tuple of three matrices: \(\langle \mathbf{R}^h, \mathbf{R}^t, \mathbf{R}^c \rangle\).

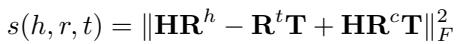

The scoring function is defined as:

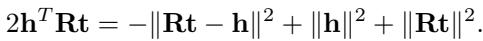

Let’s break down this equation: \(s(h,r,t) = \|\mathbf{HR}^{h} - \mathbf{R}^{t}\mathbf{T} + \mathbf{HR}^{c}\mathbf{T}\|_{F}^{2}\).

- \(\mathbf{HR}^h - \mathbf{R}^t\mathbf{T}\): This part looks similar to standard embeddings (like MQuadE). It handles the basic transformation between head and tail.

- \(+\mathbf{HR}^c\mathbf{T}\): This is the cross-term. This is the innovation. By introducing a term that multiplies the Head, the Relation (cross), and the Tail together, the researchers introduce a non-linear interaction that disrupts the “cancellation” we saw in the paradox proof.

Proof of Cure

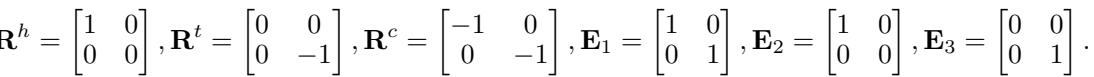

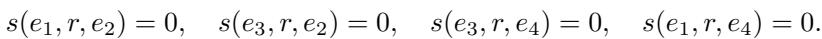

Does this actually fix the Z-paradox? The authors prove it by showing that with MQuinE, you can have a set of matrices where the Z-pattern facts are true (score = 0), but the hallucinated fact \((e_1, r, e_4)\) can be either true OR false (score = 0 or score > 0). The model has the choice.

They provide a specific construction of matrices:

Using these matrices, they show two cases. Case 1: They set \(E_4\) such that the model predicts the fourth link is false (score = 1), even though the Z-pattern exists.

Case 2: They set a different \(E_4\) such that the model predicts the fourth link is true (score = 0).

Because MQuinE can represent both scenarios, it is free from the paradox. It is no longer a slave to the geometry of the letter Z.

Maintaining Expressiveness

A “fix” is useless if it breaks other capabilities. A good KGE model must handle various relationship types:

- Symmetry: MarriedTo (If A is married to B, B is married to A).

- Inversion: ParentOf vs ChildOf.

- Composition: Father of Father is Grandfather.

- 1-to-N: One teacher has many students.

The authors provide theoretical proofs that MQuinE maintains all these capabilities.

As shown in the table above, MQuinE is the only model listed that covers every category, including avoiding the Z-paradox.

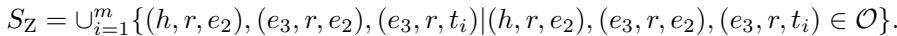

Training Strategy: Z-Sampling

Having a better architecture is step one. Step two is training it effectively. Standard KGE training uses “negative sampling”—taking a true fact \((h, r, t)\) and corrupting it to \((h, r, t')\) (a false fact) to teach the model to distinguish truth from fiction.

However, since the Z-paradox is a specific structural trap, the authors introduce Z-sampling.

The algorithm works by specifically hunting for Z-patterns in the training data.

- For a fact \((h, r, t)\), generate standard negative samples.

- Look for other entities in the graph that form a Z-pattern with these negative samples.

- Collect these “Z-pattern” triplets into a set \(S_Z\).

- The model is then explicitly trained to push the scores of these specific Z-implicated triplets apart. This forces the model to utilize the capacity of that new cross-term matrix (\(\mathbf{R}^c\)) to resolve the ambiguity.

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested MQuinE on standard benchmarks: FB15k-237 (Freebase), WN18RR (WordNet), and YAGO3-10.

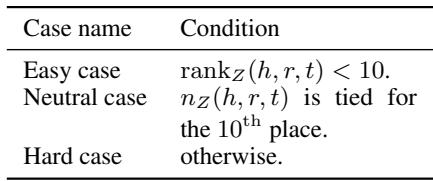

Defining “Hard” Cases

To prove the Z-paradox is real, they didn’t just look at average accuracy. They categorized test data based on “Z-value”—essentially, how many Z-patterns define a specific test fact.

- Easy: Facts not strongly implicated in Z-structures.

- Hard: Facts deeply embedded in Z-structures, where traditional models should fail.

Using this split, they analyzed the “Z-value” of existing datasets. They found that a significant portion of standard datasets like FB15k-237 falls into the “Hard” category (Table 5.2), meaning this isn’t a theoretical edge case—it’s a pervasive issue.

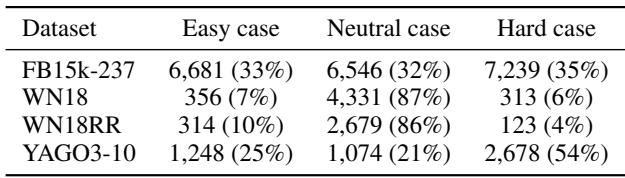

Performance on Z-Paradox Cases

The results were striking. When looking at Hard cases, traditional models like RotatE and TransE saw a massive drop in performance compared to Easy cases. This empirically confirms the Z-paradox hurts performance.

MQuinE, however, held its ground.

Look at the Hard column for FB15k-237 in the table above.

- RotatE: 39.7% accuracy (Hits@10).

- MQuinE: 52.7% accuracy.

That is a massive 13% absolute improvement on the data points most affected by the paradox. Importantly, MQuinE also performed better on the “Easy” cases (69.7% vs 67.7%), showing that the added complexity of the cross-term matrix helps general expressiveness too.

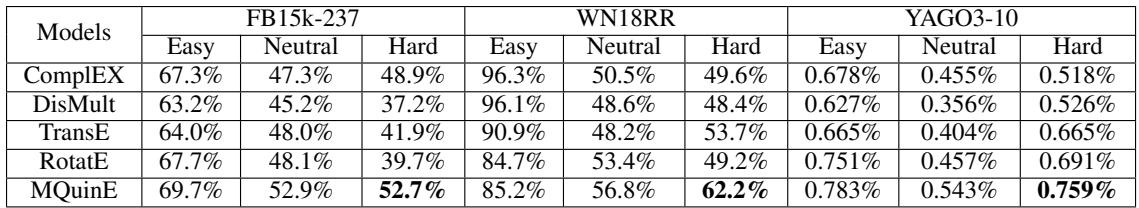

Overall Performance

When averaged across the entire datasets (not just hard cases), MQuinE achieved state-of-the-art results.

On the competitive FB15k-237 dataset, MQuinE achieved a Hits@1 score of 0.332, significantly higher than RotatE (0.241) and TuckER (0.260). This suggests that the “Z-paradox” might have been a hidden ceiling capping the performance of KGE models for years.

Similar dominance was shown on the YAGO3-10 dataset:

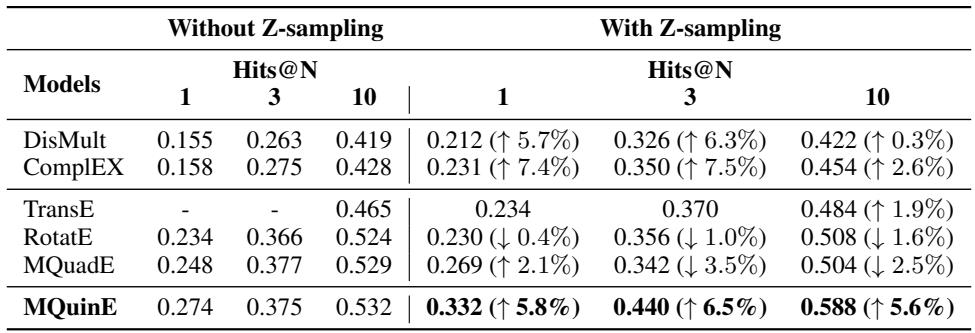

The Impact of Z-Sampling

Finally, the authors checked if the architecture alone was enough, or if the “Z-sampling” strategy was necessary.

The results show a synergy. While Z-sampling helps some models (like DisMult), it actually hurts RotatE slightly. However, for MQuinE, Z-sampling boosts performance significantly (Hits@1 jumps from 27.4% to 33.2%). This confirms that the unique architecture of MQuinE relies on this specialized sampling to fully learn how to break Z-paradox loops.

Conclusion

The “Z-paradox” is a fascinating example of how mathematical assumptions in AI models can lead to logical errors. By assuming that relationships can be modeled as simple translations (\(h+r=t\)), we inadvertently programmed our models to believe that every “Z” shape in a graph implies a closed loop.

MQuinE offers a robust solution. By expanding the representation of relations to include a cross-term (\(\mathbf{HR}^c\mathbf{T}\)), it breaks the linear chains that bind traditional models.

- It is mathematically proven to avoid the paradox.

- It retains the ability to model complex relation patterns.

- It significantly outperforms existing baselines, especially on difficult, paradox-prone data.

For students and researchers in knowledge graphs, MQuinE highlights the importance of questioning the geometric assumptions underlying our embeddings. Sometimes, to think outside the box, you need to break the Z.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.03583/images/cover.png)