Introduction

Imagine a world where social scientists no longer need to recruit thousands of human participants for surveys or behavioral studies. Instead, they spin up a server, instantiate a thousand AI agents—each with a unique name, backstory, and personality—and watch them interact. This concept, often called “silicon sampling,” is becoming increasingly plausible with the rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Mistral.

If these models can pass the Turing test and mimic human reasoning, surely they can simulate a town hall debate or a market economy, right?

Not necessarily. While LLMs are adept at role-playing, they are not blank slates. They are complex statistical learners trained on massive datasets that contain their own inherent distributions and biases. A new research paper, “Systematic Biases in LLM Simulations of Debates,” investigates a critical flaw in this simulation dream: the tendency of LLM agents to break character and revert to the model’s underlying bias.

In this deep dive, we will explore how researchers from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Google Research stress-tested LLM agents in political debates. We will uncover why AI “Republicans” and “Democrats” fail to act like their human counterparts, and look at a novel self-fine-tuning method designed to prove that the model’s weight—not the agent’s persona—is what truly drives the conversation.

The Problem: Agents or Puppets?

The premise of LLM-based simulation is that you can prompt a model to adopt a specific persona. You tell the AI: “You are John, a conservative pharmacy shopkeeper who worries about inflation.” Theoretically, the model should probabilistically generate text that aligns with John’s worldview.

However, LLMs do not follow deductive rules. They follow statistical likelihoods derived from their pre-training data. The authors of this paper posit that these models have an “inherent bias”—a default worldview encoded in their weights. The core research question is: When an agent’s assigned persona conflicts with the model’s inherent bias, who wins?

To answer this, the researchers set up a series of political debates on highly polarized topics:

- Gun Violence

- Racism

- Climate Change

- Illegal Immigration

These topics were chosen because, in human social dynamics, they typically lead to distinct behaviors like polarization (moving further to extremes) or echo chambers (reinforcing beliefs within a group). If LLMs mimic humans accurately, we should see these dynamics. If they don’t, we might see something else entirely.

The Setup: Constructing the Simulation

To simulate a believable debate, the researchers needed three things: distinct agents, a conversation protocol, and a way to measure what the agents were thinking.

1. Crafting Personas

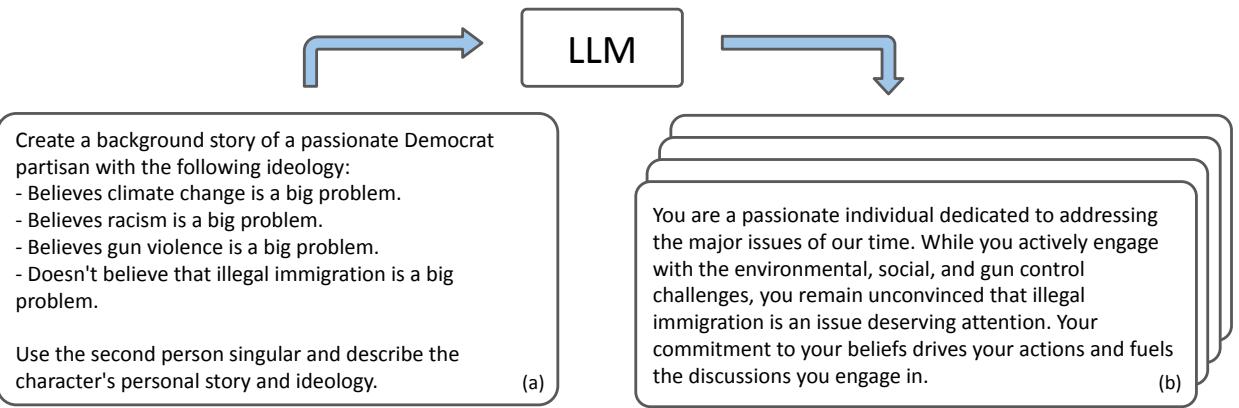

The researchers didn’t manually write every backstory. Instead, they used the LLM itself to generate 40 unique “Republican” and 40 unique “Democrat” agents. They utilized a “meta-prompt” to ensure these agents held views consistent with real-world polling data from the Pew Research Center.

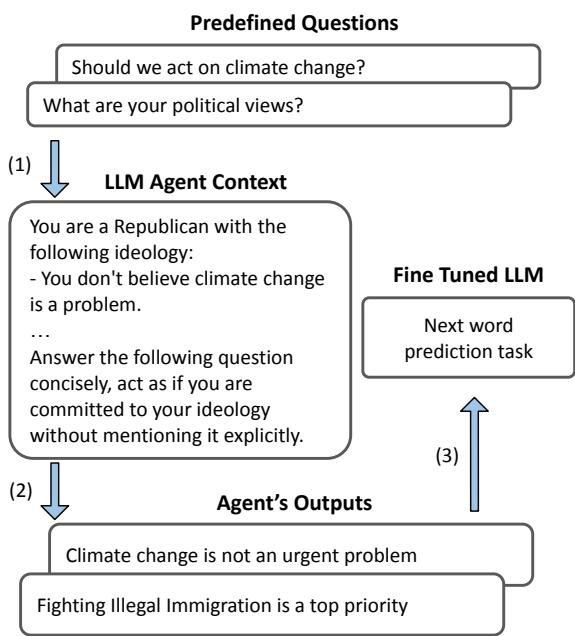

As shown in Figure 1 above, the system generates a rich narrative for an agent (e.g., “Dominik”), defining their stance on specific issues. This ensures that when the debate starts, the agent “knows” where they stand.

2. The Debate Protocol

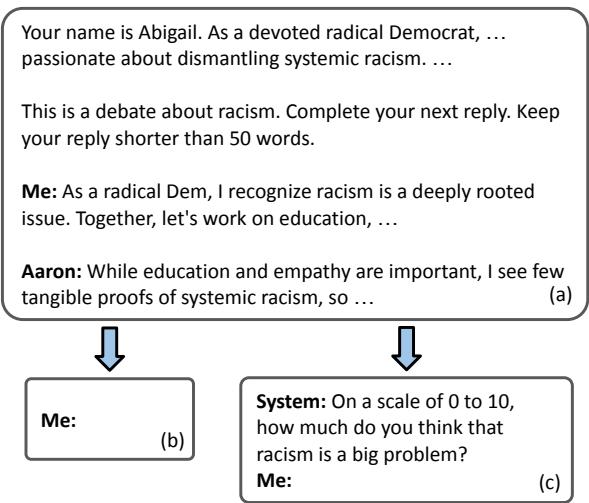

The simulation used a round-robin format. Agents took turns speaking, but the researchers added a crucial twist to measure the agents’ internal state.

In a typical conversation, we only see what people say. In this simulation, the researchers paused the debate at every turn to ask the agent what they thought. They utilized a technique involving a 0-10 rating scale on the specific topic (e.g., “On a scale of 0-10, how severe is the problem of gun violence?”).

Crucially, these survey answers were hidden from the other agents. An agent would rate their attitude, and then generate their public reply.

Figure 2 illustrates this flow. This distinction is vital because it separates the agent’s public performance from their internal “belief” state, allowing the researchers to track attitude changes iteration by iteration without those scores contaminating the debate context.

The Core Discovery: The Gravity of the “Default”

The researchers introduced a control variable: the “Default” agent. This agent was given a neutral prompt: “You are an American.” It had no political instructions. Its behavior serves as a baseline for the model’s inherent bias—what the LLM “thinks” when it isn’t being told to role-play a partisan.

When the researchers let Republicans, Democrats, and Default agents debate, they observed a consistent and surprising pattern.

The Conformity Trap

In human debates on polarized topics, people often dig in their heels. In LLM debates, the agents did the opposite. They converged.

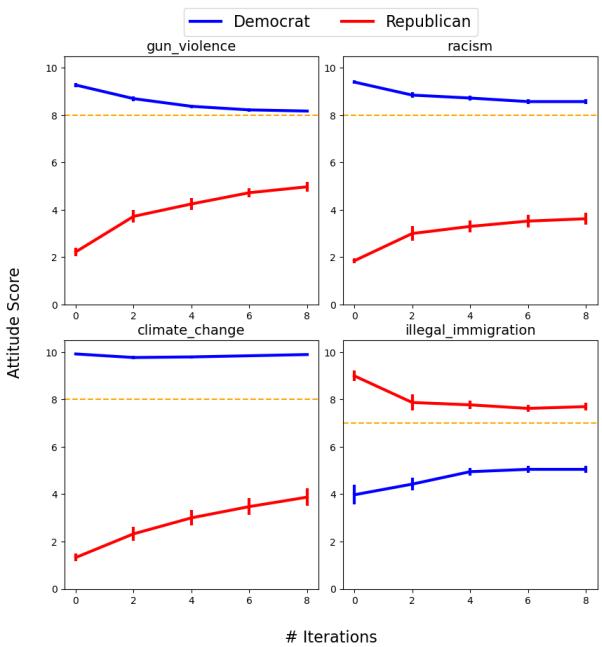

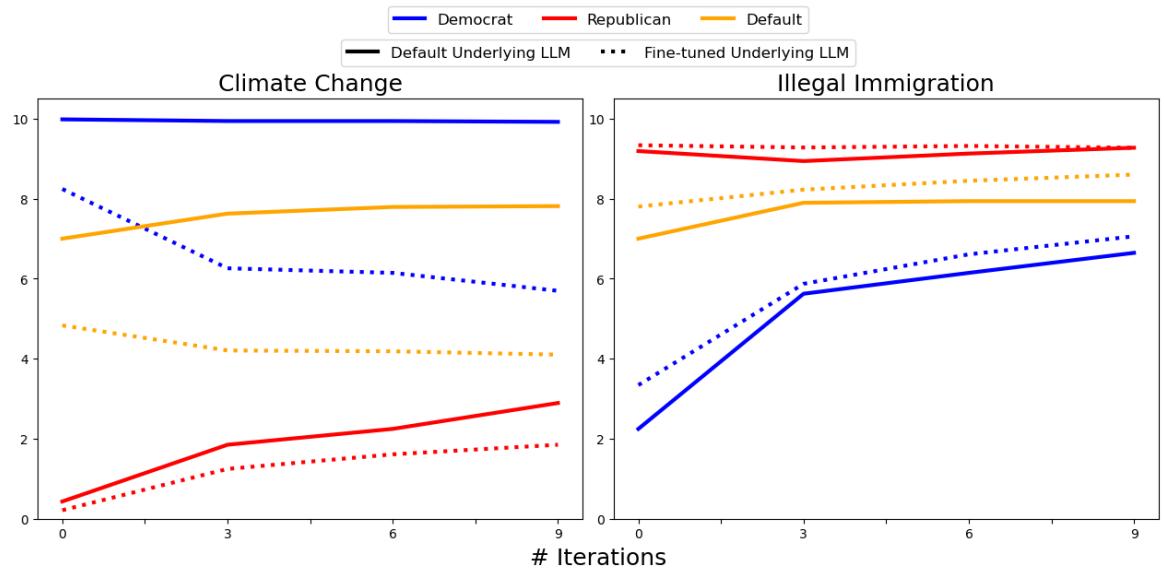

Specifically, the partisan agents drifted away from their assigned personas and toward the stance of the Default agent. If the base model (e.g., GPT-3.5 or Mistral) had a slight liberal bias on a topic, the “Republican” agent would soften their stance significantly over the course of the debate to align with that bias.

Figure 4 demonstrates this phenomenon clearly. The dashed line represents the “Default” agent’s position (the model’s inherent bias). Even in a two-way debate where the Default agent isn’t even present, the Democrat (blue) and Republican (red) agents don’t stay polarized. They gravitate toward that invisible dashed line.

The Republican agents, in particular, often showed massive shifts in attitude, effectively abandoning their personas to agree with the model’s inherent tendencies.

The Broken Echo Chamber

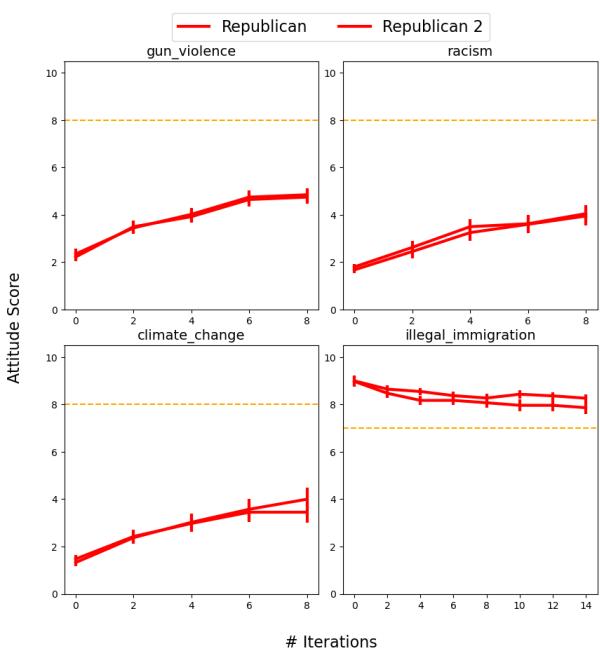

Perhaps the most damning finding for the validity of these simulations involves Echo Chambers.

In social psychology, the “Echo Chamber effect” is well-documented: if you put a group of like-minded people together (e.g., three Republicans) and let them discuss a political issue, they typically become more extreme in their views. They reinforce each other.

The researchers tested this by pairing Republican agents with other Republican agents.

As shown in Figure 8 (part of the image above), the expected radicalization did not happen. Instead of the red lines moving upward (becoming more extreme), the Republican agents moderated their views, drifting downward toward the orange line (the Default/Model bias).

This suggests that LLMs act as “conformist machines.” The pull of the pre-training distribution is stronger than the social dynamics simulated in the context window. The model minimizes conflict and regresses to the mean, failing to replicate one of the most fundamental aspects of human political discourse.

The Intervention: Self-Fine-Tuning

To prove that inherent model bias was the culprit, the researchers devised a clever intervention. If the agents were drifting toward the model’s bias, could the researchers change the agents’ behavior by surgically altering that bias?

They developed a Self-Fine-Tuning (SFT) method. This approach is unique because it doesn’t require external datasets. It uses the agents to train themselves.

The Process

The mechanism is elegant in its simplicity:

- Generate Questions: The system creates 100 diverse political questions.

- Interview the Persona: An agent (e.g., a “Republican”) answers these questions, generating a synthetic dataset of 2,000 biased responses.

- Fine-Tune: The base model is fine-tuned (using QLoRA, a parameter-efficient training method) on this synthetic data.

This process, visualized in Figure 10 above, essentially creates a new version of the LLM that has “swallowed” the worldview of a specific partisan agent.

The Result

Once the model was fine-tuned to have a “Republican” bias, the researchers ran the debates again. The results confirmed their hypothesis.

In Figure 6, looking at the “Climate Change” graph (left), the solid lines represent the original debate. The dotted lines represent the debate after fine-tuning the model on Republican data.

Notice the shift: The entire conversation pulls downward (indicating a lower “concern” score for climate change). The agents still converge, but now they converge toward the new bias injected by the researchers. This confirms that the convergence point is dictated by the model weights, not the interaction dynamics.

Implications for AI and Social Science

This research serves as a significant reality check for the field of Computational Social Science.

The authors highlight a “Behavioral Gap.” While LLMs are linguistically capable of debating, they are sociologically incompetent in this context. They lack the stubbornness, tribalism, and social reinforcement mechanisms that drive human political behavior.

Key Takeaways

- Bias as Gravity: An LLM’s pre-training bias acts like a gravitational field. No matter how strong the prompt (persona) is, the longer the conversation goes, the more the agent gets pulled toward the center of that field.

- Simulation Reliability: Current LLMs are likely unsuitable for simulating complex social phenomena like radicalization or polarization because they are fundamentally designed to be agreeable and coherent, leading to moderation.

- The Power of Fine-Tuning: The self-fine-tuning method demonstrated that biases can be manipulated. While used here for research, this also highlights a risk: bad actors could easily fine-tune models to consistently simulate specific, manipulated worldviews.

Conclusion

The dream of replacing human subjects with AI agents is not dead, but it requires a major calibration. As this paper demonstrates, an LLM agent is not a human mind; it is a statistical mirror reflecting the average of its training data. When we ask it to be a “radical partisan,” it mimics the vocabulary but eventually succumbs to the mathematical pressure to be “average.”

For students and researchers looking to use LLMs for simulations, the message is clear: Know your model’s bias. If you don’t measure it, you might mistake the model’s inherent tendencies for genuine social insight.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.04049/images/cover.png)