Introduction

The rapid rise of Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) like LLaVA, mPLUG-Owl, and GPT-4V has revolutionized how machines understand the world. By aligning visual encoders with powerful Large Language Models (LLMs), these systems can look at an image and describe it, answer complex questions about it, or even reason through visual problems. However, despite their impressive capabilities, these models suffer from a critical and often embarrassing flaw: Object Hallucination.

Object hallucination occurs when an LVLM confidently describes objects in an image that simply aren’t there. For a casual user, this might result in a funny caption. But in safety-critical domains—such as medical imaging analysis or autonomous navigation—a model “seeing” a tumor that doesn’t exist or a stop sign that isn’t present poses severe risks.

Previous attempts to fix this have relied on expensive solutions. Some researchers curate massive, high-quality datasets to fine-tune the models, which is computationally heavy and costly. Others use “post-generation correction,” asking proprietary models like GPT-4 to double-check the LVLM’s work, which adds significant latency and API costs.

In the paper Mitigating Object Hallucination in Large Vision-Language Models via Image-Grounded Guidance, researchers introduce a novel framework called MARINE. It stands for “Mitigating hallucinAtion via image-gRounded guIdaNcE.” The standout feature of MARINE is that it is both training-free and API-free. It reduces hallucinations during the inference stage by leveraging open-source vision models to guide the LLM, ensuring that the text generation remains grounded in visual reality.

Background: Why Do LVLMs Hallucinate?

To understand how MARINE works, we first need to diagnose the patient. Why do highly capable models make up objects? The authors identify three primary root causes deficiencies within the standard LVLM architecture:

- Insufficient Visual Context: The visual encoder (often CLIP-based) used by LVLMs is excellent at capturing the general “vibe” or semantic meaning of an image but often lacks fine-grained object-level precision.

- Information Loss: When visual features are projected into the text embedding space (translating “pixels” to “tokens”), vital details can be distorted or lost.

- LLM Priors: The language model component acts like a powerful autocomplete. If it sees a picture of a dining table, its statistical priors might predict “fork” and “knife” next, even if those specific objects aren’t visible in the image.

MARINE specifically targets the first two issues by injecting high-quality, explicit visual information into the generation process.

The MARINE Framework

The core philosophy of MARINE is that if the LVLM’s internal eyes (its visual encoder) are a bit blurry, we should give it a pair of glasses. These “glasses” come in the form of off-the-shelf, open-source object detection models.

1. The Vision Toolbox

Instead of relying solely on the LVLM’s native visual encoder, MARINE introduces a “Vision Toolbox.” This toolbox contains specialized models designed explicitly for object grounding—such as DETR (DEtection TRansformer) or RAM++ (Recognize Anything Model).

Unlike the general-purpose encoders in LVLMs, these specialized models are trained to do one thing very well: detect and list objects present in an image.

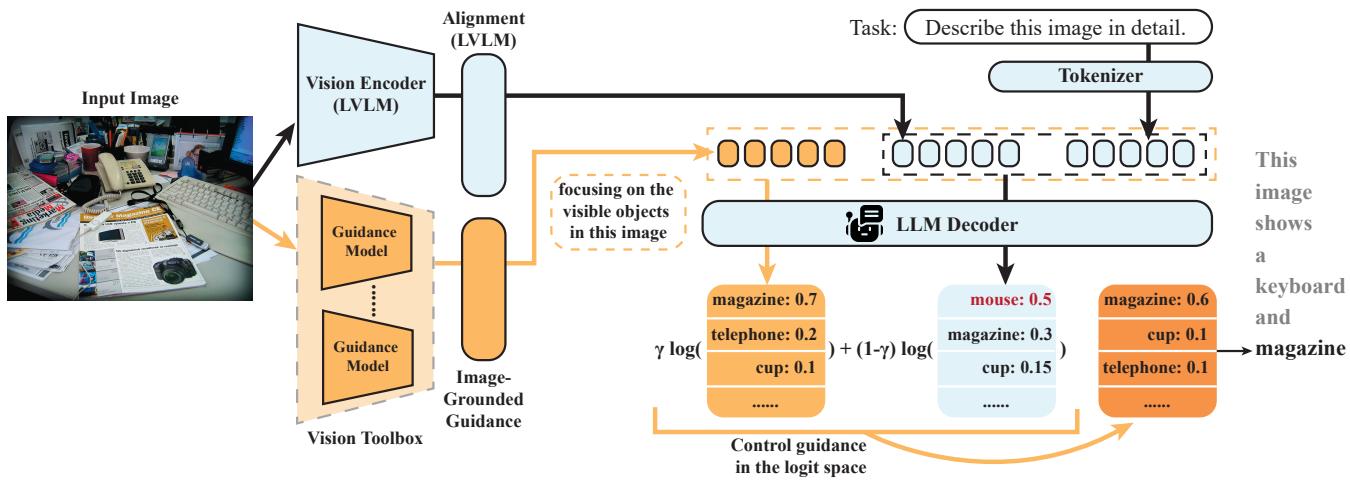

As illustrated in the architecture diagram below, the system takes an input image and processes it through two parallel paths. The standard path goes through the LVLM’s visual encoder. The secondary path goes through the “Guidance Models” in the vision toolbox.

The guidance models detect objects (e.g., “keyboard,” “mouse,” “cup”) and aggregate them into a textual context. This aggregated information acts as a reliable “ground truth” list of what is actually visible.

2. Classifier-Free Guidance for Text Generation

How does MARINE force the LVLM to pay attention to this new object list? It uses a technique inspired by Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG), a method popularized by image generation models (like Stable Diffusion) to make images adhere closer to text prompts.

MARINE adapts this for text generation. It treats the detected object list as a control condition (\(c\)).

During inference, the model computes two sets of probabilities (logits) for the next word in the sentence:

- Unconditional Logits: The standard prediction based on the image features (\(v\)) and the text prompt (\(x\)).

- Conditional Logits: The prediction based on the image features (\(v\)), the text prompt (\(x\)), and the aggregated object guidance (\(c\)).

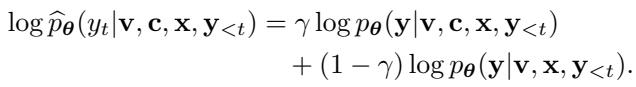

The method then effectively subtracts the unconditional prediction from the conditional one to amplify the influence of the guidance. The mathematical formulation for the updated probability distribution is:

In this equation:

- \(\log \widehat{p}_{\theta}\) is the final, adjusted score for a potential next word.

- \(\mathbf{c}\) represents the visual guidance (the list of detected objects).

- \(\gamma\) (gamma) is the guidance strength.

If \(\gamma = 1\), the model relies entirely on the guidance. If \(\gamma = 0\), it acts like the standard model. By tuning \(\gamma\) (usually between 0.3 and 0.7), the authors find a “sweet spot” where the model uses the external object detections to suppress hallucinations without losing its ability to write coherent, fluid sentences.

Essentially, if the standard LLM wants to predict “fork” because it’s completing a sentence about a dinner table, but the object detection model didn’t see a fork (meaning the conditional probability for “fork” is low), the formula will heavily penalize the “fork” token, preventing the hallucination.

Experiments and Results

The researchers tested MARINE across five popular LVLMs (including LLaVA, MiniGPT-v2, and InstructBLIP) using standard benchmarks for hallucination.

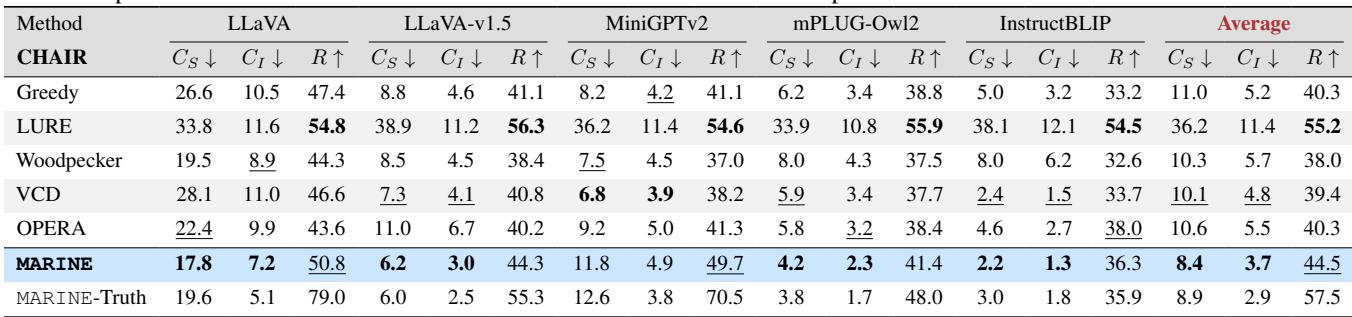

Reducing Hallucinations (CHAIR Metric)

The primary metric used is CHAIR (Caption Hallucination Assessment with Image Relevance). This metric calculates what percentage of objects mentioned in a caption do not actually exist in the ground truth annotations. Lower scores are better.

The table below details the performance comparison. MARINE achieves the lowest hallucination rates (Best results in bold) across almost every model architecture.

For example, looking at the LLaVA model, the standard version has a \(CHAIR_S\) (Sentence-level hallucination) score of 26.6. When equipped with MARINE, this drops to 17.8. This is a massive improvement, significantly outperforming other baseline methods like LURE or Woodpecker.

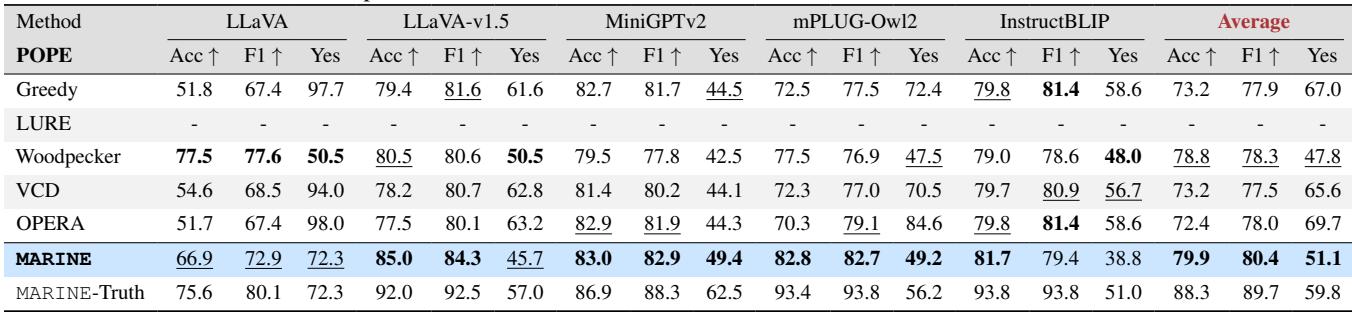

The “Yes” Bias (POPE Metric)

Another common way to test hallucinations is the POPE (Polling-based Object Probing Evaluation) benchmark. This involves asking the model binary “Yes/No” questions, such as “Is there a dining table in the image?”

LVLMs suffer from severe over-trust or “Yes bias”—they tend to answer “Yes” to almost anything if the object is contextually likely, even if it’s not there.

The results in Table 2 show that MARINE significantly improves accuracy. More importantly, look at the “Yes” ratio. A perfectly unbiased model answering adversarial questions (where 50% of objects are absent) should have a Yes ratio near 50%. Standard LLaVA has a Yes ratio of 97.7%, meaning it almost always claims objects exist. MARINE brings this down to 72.3%, reflecting a much more grounded and honest decision-making process.

Qualitative Examples

Numbers are great, but seeing is believing. The figure below visualizes how MARINE corrects errors in real-time.

In the top example with the bird, the standard LLaVA model hallucinates a “white chair” simply because the bird is white and sitting on something. MARINE correctly identifies that “there is no chair in the image,” focusing only on the bird. In the kitchen scene (bottom), MARINE prevents the model from listing generic kitchen items that aren’t visible, instead accurately listing the microwave and coffee maker.

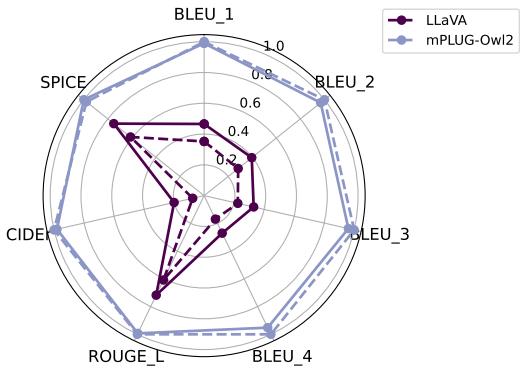

Does it hurt text quality?

A common fear with guidance methods is that they might make the output text robotic or repetitive. The researchers evaluated the general text quality using metrics like BLEU and ROUGE (which measure similarity to human reference captions).

As shown in the radar chart, the solid lines (MARINE) almost perfectly overlap or exceed the dashed lines (Original). This confirms that MARINE reduces hallucinations without degrading the fluency or richness of the language generation.

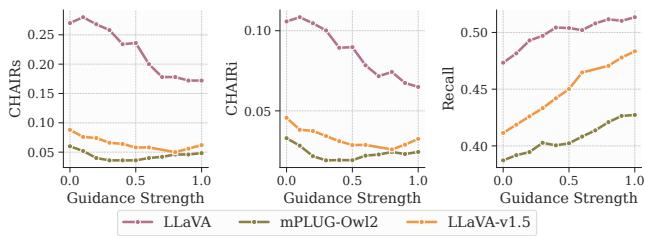

Ablation: Tuning the Guidance

The researchers also performed ablation studies to understand how different components affect performance. One key factor is the guidance strength (\(\gamma\)).

The graphs above show that as guidance strength increases (moving right on the x-axis), hallucination (CHAIR score) decreases. However, if \(\gamma\) gets too high (close to 1.0), the model might become too rigid. The study suggests a middle ground is optimal for balancing accuracy with instruction following.

Additionally, they found that using an intersection of detections from different vision models (e.g., combining DETR and RAM++) provided better results than using a union. Taking the intersection filters out noise—an object is only considered “present” if multiple expert models agree on it.

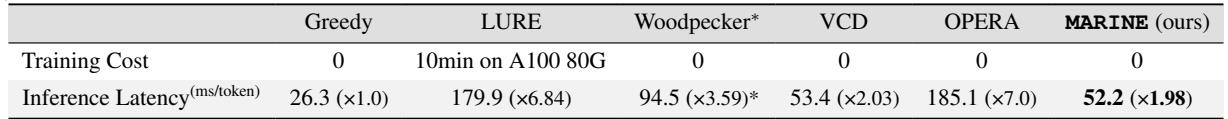

Efficiency

Finally, a major advantage of MARINE is speed. Post-processing methods like Woodpecker require sending data to GPT-4V or running a second large model to rewrite captions, which is slow.

MARINE works during the decoding process itself. As shown in Table 5, the latency overhead is minimal (roughly 2x the standard greedy decoding, compared to 7x for methods like LURE or OPERA). This makes it feasible for real-time applications.

Conclusion and Implications

The MARINE framework presents a compelling step forward for multimodal AI. By acknowledging that general-purpose Vision-Language Models have “blind spots,” the authors devised a way to augment them with specialized, image-grounded tools.

Key takeaways include:

- Training-Free: MARINE improves existing models like LLaVA and InstructBLIP immediately without requiring expensive retraining or fine-tuning datasets.

- Modular: It is compatible with various external vision models. As object detection technology improves, MARINE improves automatically.

- Effective: It attacks the root cause of hallucination (lack of visual grounding) rather than just treating the symptoms, achieving state-of-the-art results on hallucination benchmarks.

For students and researchers entering the field, MARINE illustrates an important lesson: sometimes the solution isn’t a bigger model or more data, but a smarter architecture that allows different specialized systems to collaborate. By grounding language generation in verified visual evidence, we move closer to AI systems that are not just fluent, but truthful.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.08680/images/cover.png)