Beyond One-Shot: How PROMST Masters Multi-Step Prompt Engineering

If you have ever worked with Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 or Claude, you are intimately familiar with the “dark art” of prompt engineering. You tweak a word here, add a constraint there, and cross your fingers that the model outputs what you want.

While this trial-and-error process is manageable for simple tasks—like summarizing an email or solving a math problem—it becomes a nightmare when building autonomous agents. Imagine an LLM controlling a robot in a warehouse or a web agent navigating a complex e-commerce site. These are multi-step tasks. They require planning, long-horizon reasoning, and adherence to strict environmental constraints.

If a robot crashes into a wall on step 15, was the prompt wrong? Or was it just bad luck? How do you optimize the instructions when the feedback loop is so long and complex?

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into PROMST (PRompt Optimization in Multi-Step Tasks), a research paper that proposes a robust framework for automating this process. By combining human-designed feedback rules with a learned scoring model, PROMST demonstrates how we can move from manual tinkering to automated, high-performance agent design.

The Multi-Step Challenge

Before we dissect the solution, we must understand the problem.

Most existing research on Automatic Prompt Optimization (APO) focuses on single-step tasks. For example, in a dataset of math word problems, the model takes an input and produces an output. If the answer is wrong, the “loss” is immediate and clear.

Multi-step tasks introduce three compounding difficulties:

- Complexity: The prompts are usually long (300+ tokens), containing detailed instructions about valid moves, inventory management, and safety protocols.

- Credit Assignment: If an agent fails a task, it is difficult to determine which specific part of the prompt caused the failure. Did the agent misunderstand the “pickup” command, or did it fail to plan the path to the object?

- Preferences: Different users might want the task done differently. One might prioritize speed, while another prioritizes safety (avoiding collisions).

Humans struggle to optimize these prompts because the search space is infinite. However, humans are excellent at one thing: spotting errors. We can easily look at a log and say, “The agent got stuck in a loop” or “The agent tried to walk through a wall.”

PROMST leverages this human ability to critique, combined with the LLM’s ability to rewrite, to create a powerful optimization loop.

The PROMST Framework

The core idea of PROMST is to treat prompt engineering as an evolutionary search problem, but one guided by specific feedback and heuristics to make it efficient.

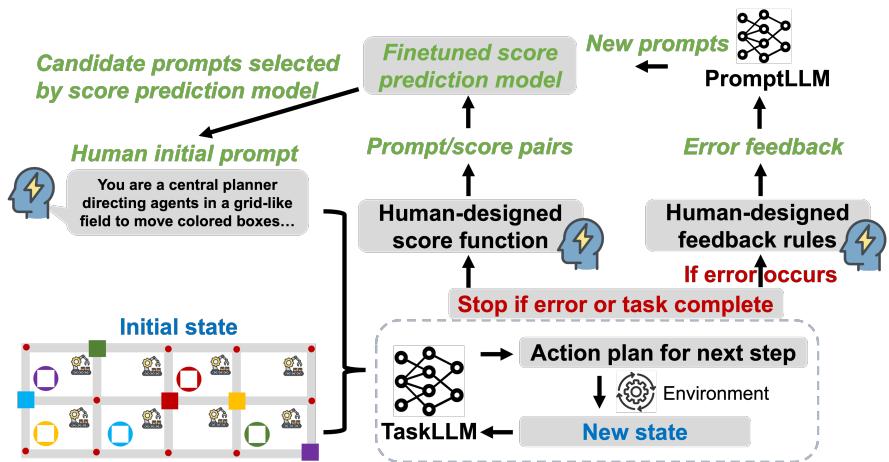

As illustrated in Figure 1, the framework operates in a cycle involving three main components:

- TaskLLM: The agent interacting with the environment (e.g., GPT-3.5 or GPT-4).

- PromptLLM: A separate LLM responsible for analyzing feedback and generating improved prompts.

- Score Prediction Model: A heuristic model that filters out bad prompts before we waste resources testing them.

Let’s break down how these pieces fit together.

1. The Feedback Loop: Human Rules meet AI Reasoning

In a typical optimization loop, an LLM might look at a failure and try to “guess” what went wrong. However, in complex environments, LLMs often hallucinate the cause of the error.

PROMST stabilizes this by using Human-Designed Feedback Rules. These are not complex code, but simple templates that categorize errors.

As shown in the image above (left side), the system categorizes errors into specific types:

- Syntactic Error: The model output didn’t match the required JSON or text format.

- Stuck in a Loop: The agent repeated the same action sequence without progress.

- Collision: The agent tried to move into an occupied space.

- Invalid Action: The agent tried to use a tool it doesn’t have.

When the TaskLLM fails, the system doesn’t just say “Fail.” It fills in one of these templates. For example: “Error: Stuck in the loop. You performed the action ‘Move North’ 5 times without changing state.”

This structured feedback is passed to the PromptLLM. The PromptLLM then acts as a “meta-optimizer.” It reads the current prompt, reads the specific error feedback, and rewrites the prompt to explicitly address that failure mode.

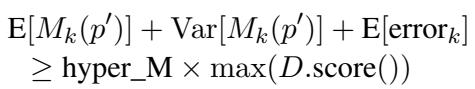

2. The Objective Function

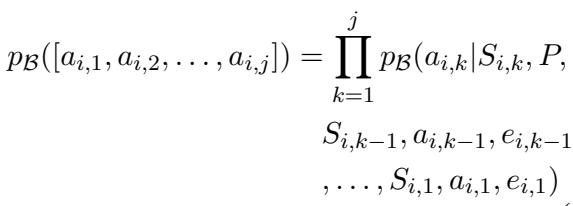

Mathematically, the goal is to find a prompt \(P^*\) that maximizes the expected reward across a set of tasks.

The equation above represents the probability of an action sequence. The PROMST framework seeks to maximize a score function \(R\) over all testing trials \(U\):

Here, \(R\) is usually a “Task Progress Score”—the ratio of completed sub-goals to total sub-goals.

3. The Efficiency Hack: The Score Prediction Model

One of the biggest bottlenecks in prompt optimization is cost. Validating a prompt for a multi-step task is expensive. You have to run the agent through a simulation, which might take dozens of steps (and API calls). If you generate 100 candidate prompts, you cannot afford to test them all fully.

PROMST introduces a Score Prediction Model to solve this.

This is a fine-tuned model (based on Longformer) that learns to predict how well a prompt will perform just by reading the prompt text.

- Phase 1 (Exploration): In the early generations, the system runs the expensive tests to gather data. It collects pairs of

(Prompt Text, Actual Score). - Phase 2 (Exploitation): Once enough data is gathered, the Score Prediction Model is trained. For subsequent generations, the PromptLLM generates many candidates, but the Score Prediction Model acts as a gatekeeper.

As seen in the equation above, a candidate prompt \(p'\) is only selected for real-world testing if its predicted score (plus variance and error margins) exceeds a certain threshold relative to the current best scores. This allows PROMST to explore the prompt space broadly without burning through API credits on obviously bad prompts.

Experimental Setup

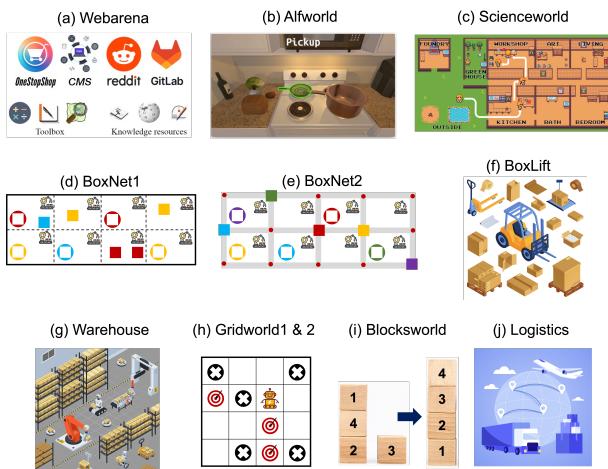

The researchers evaluated PROMST across 11 representative multi-step tasks, ranging from digital agents to embodied robot simulations. These environments (shown in Figure 3 of the image deck) include:

- WebArena: A realistic simulation of web browsing (shopping, reddit, CMS).

- ALFWorld: Text-based household tasks (e.g., “clean the apple and put it in the fridge”).

- BoxLift / Warehouse / Logistics: Grid-world planning tasks involving moving objects, avoiding collisions, and coordinating multiple agents.

- ScienceWorld: A complex text adventure requiring scientific reasoning.

They compared PROMST against several strong baselines, including:

- APE (Automatic Prompt Engineer)

- APO (Automatic Prompt Optimization)

- PromptAgent (A state-of-the-art method using Monte Carlo Tree Search)

- PromptBreeder (Evolutionary algorithms)

Key Results: Dominating the Benchmarks

The results were statistically significant. PROMST consistently outperformed both human-engineered prompts and the automated baselines.

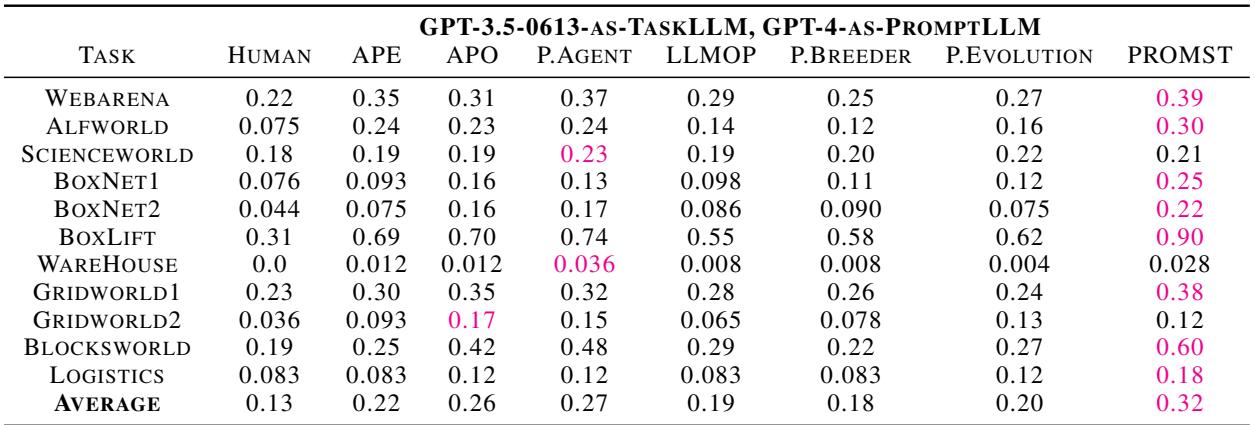

Performance on GPT-3.5 and GPT-4

The table below details the performance when using GPT-3.5 as the Task Agent. PROMST achieves the highest average score (0.32), significantly beating the next best method, PromptAgent (0.27).

The lead extends further when using GPT-4. PROMST achieves an average score of 0.69, compared to the human baseline of 0.51 and PromptAgent’s 0.61.

Notable wins include:

- BoxLift: A massive jump from 0.31 (Human) to 0.90 (PROMST) on GPT-3.5.

- Blocksworld: Improving from 0.71 (Human) to 0.95 (PROMST) on GPT-4.

- Gridworld: Consistent improvements in pathfinding logic.

Why Does It Work? The Impact of Components

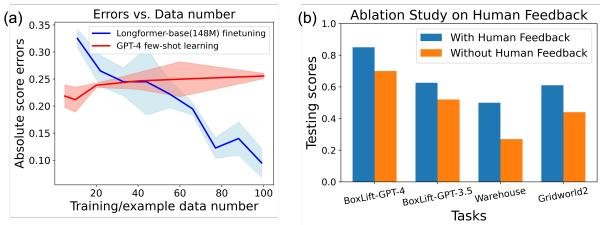

To understand why PROMST works, the authors performed ablation studies—removing parts of the system to see what breaks.

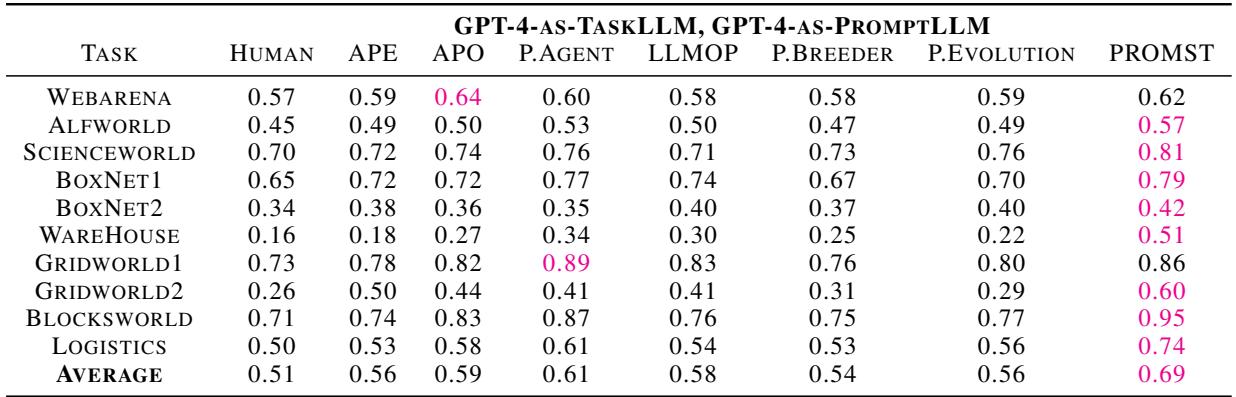

1. The Power of the Score Prediction Model

Figure 4(a) shows the distribution of scores. The red bars (with the score model) are shifted significantly to the right compared to the green bars (without). This proves the model successfully filters out low-quality prompts.

Figure 4(d) illustrates the optimization trajectory. The green line (Training with score model) converges much faster and to a higher score than the blue line (Training without score model). It essentially “accelerates” evolution.

2. The Necessity of Human Feedback

Is the human feedback rule set actually necessary? Could the LLM just figure it out?

Figure 5(b) offers a stark answer. In tasks like BoxLift and Warehouse, removing human feedback (the orange bars) causes a massive drop in performance compared to the full PROMST method (blue bars). This validates the hypothesis that while LLMs are good optimizers, they need structured, ground-truth error signals to know what to optimize.

Deep Dive: What Makes a “Good” Prompt?

One of the most interesting aspects of this research is the analysis of the generated prompts. What exactly is PROMST writing that makes the agents perform better?

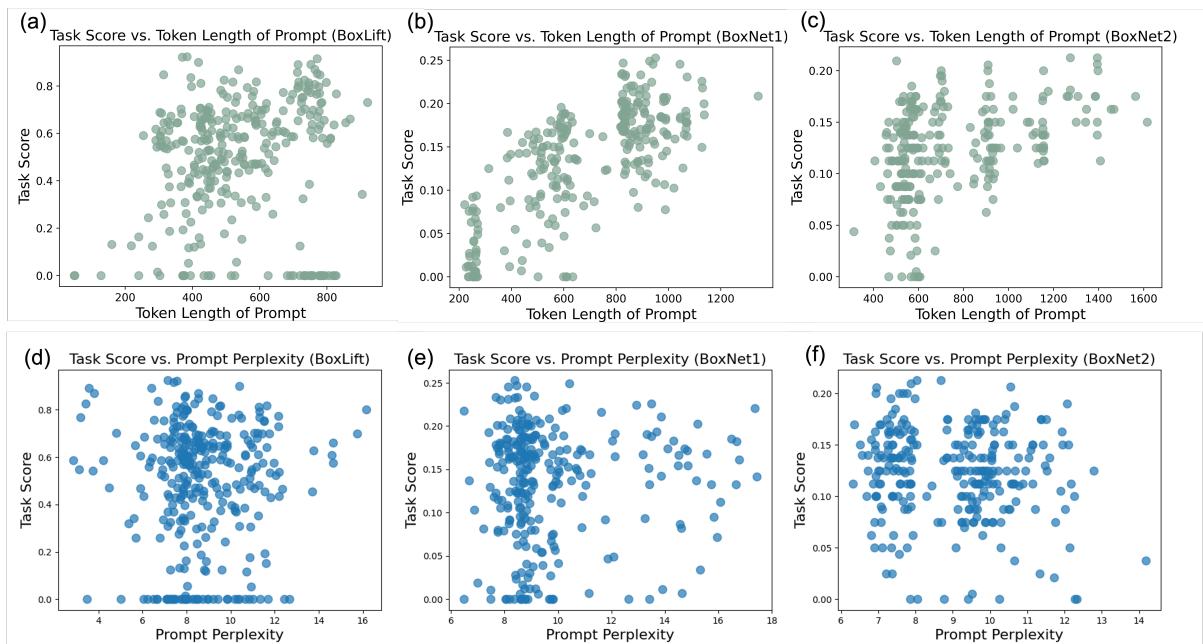

1. Longer is (Usually) Better

Contrary to the belief that concise prompts are better for token efficiency, PROMST discovered that for multi-step reasoning, detail matters.

As shown in Figure 13 (top row), there is a general correlation between prompt length and task score. The optimized prompts tend to include explicit checklists, edge-case handling, and step-by-step reasoning protocols.

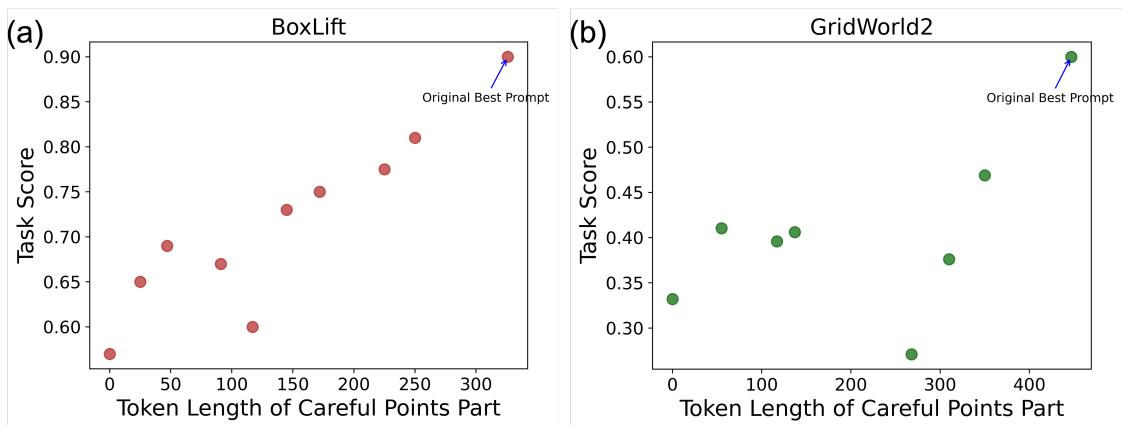

2. Clarity and Structure

The researchers found that the best prompts often “list careful points one by one clearly.” To test this, they took the best PROMST-generated prompt and asked GPT-4 to summarize it (shorten it).

Figure 14 shows a direct linear relationship: as you compress the instructions (reducing token length), the score drops. This suggests that the “verbosity” isn’t fluff—it’s necessary cognitive scaffolding for the model.

3. Aligning with Human Preferences

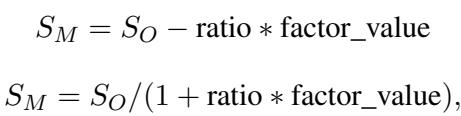

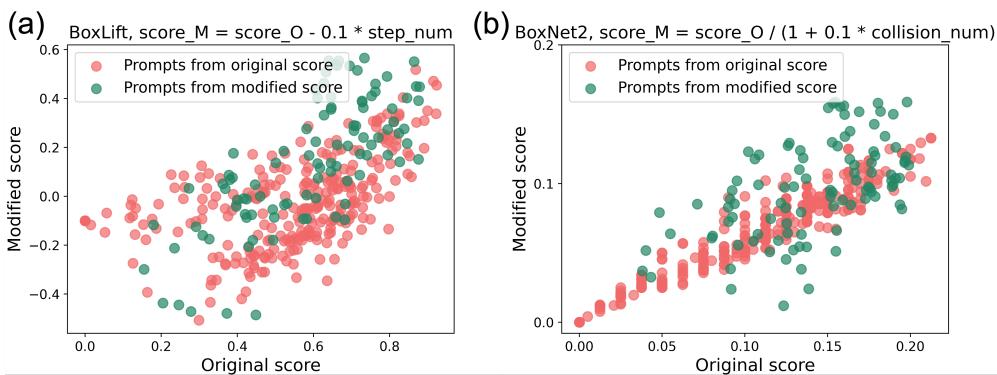

A prompt that achieves the goal might still be “bad” if it does so inefficiently or dangerously. For example, in a robot navigation task, we might care about minimizing steps and avoiding near-collisions.

The paper explores modifying the score function to include penalties for bad behavior (like high step counts or collisions).

By tweaking the scoring formula (shown above) to penalize step count (step_num) or collision count (factor_value), PROMST successfully steered the optimization.

Figure 12 shows the results of this alignment. The green dots represent prompts optimized with the modified scoring rules. In Figure 12(a), the green dots cluster lower on the Y-axis (Modified Score) but maintain high completion rates, indicating the model learned to balance the trade-off between just finishing the task and finishing it efficiently.

Conclusion and Future Implications

PROMST represents a significant step forward in making autonomous agents reliable. It acknowledges that while LLMs are powerful, they are not yet fully self-correcting in complex environments. By injecting a small amount of human domain knowledge (via feedback rules) and using intelligent sampling (via the score model), we can unlock performance capabilities that manual engineering simply cannot match.

Key Takeaways for Students & Practitioners:

- Don’t rely on generic feedback: For complex agents, create specific error categories (loops, syntax, logic).

- Evaluation is the bottleneck: If you can build a cheaper heuristic to predict prompt quality, do it. It allows you to search a much larger space.

- Verbosity has value: In multi-step planning, explicit, detailed instructions often outperform concise ones.

As we move toward more general-purpose agents, frameworks like PROMST will likely become the standard for “compiling” high-level human intent into executable agent behaviors. The era of guessing and checking prompts is ending; the era of optimizing them is just beginning.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.08702/images/cover.png)