Named Entity Recognition (NER) is one of the bread-and-butter tasks of Natural Language Processing. Whether it is extracting stock tickers from financial news, identifying proteins in biomedical papers, or parsing dates from legal contracts, NER is everywhere.

For years, the standard workflow for building a custom NER model has been rigid: take a pre-trained foundation model like BERT or RoBERTa, hire humans to annotate thousands of examples for your specific entities, and fine-tune the model. This process is slow, expensive, and inflexible.

With the rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4, we gained a new option: just ask the LLM to find the entities. While this works well, it is computationally heavy and expensive to run at scale. You don’t want to burn through GPT-4 credits just to parse millions of invoices.

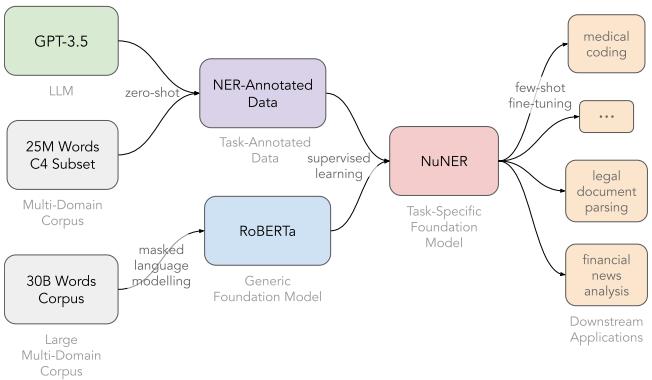

This brings us to a fascinating paper: “NuNER: Entity Recognition Encoder Pre-training via LLM-Annotated Data.” The researchers propose a hybrid approach that combines the intelligence of massive LLMs with the efficiency of small encoders. By using an LLM to annotate a massive, generic dataset, they created NuNER, a compact model that outperforms its peers and rivals models 50 times its size.

In this post, we will break down how NuNER works, why its “contrastive” training method is a game-changer for NER, and what this means for the future of task-specific foundation models.

The Concept: Task-Specific Foundation Models

To understand NuNER, we first need to look at the current landscape of transfer learning.

- General Foundation Models: Models like BERT or RoBERTa are trained on raw text (Masked Language Modeling). They understand English syntax and semantics but don’t know what a “protein” or “legal defendant” is until you fine-tune them.

- Domain-Specific Models: Models like BioBERT are pre-trained on biomedical text. They understand the jargon but still need fine-tuning for specific tasks.

NuNER introduces a different category: a Task-Specific Foundation Model. It is a small model (based on RoBERTa) that has been pre-trained specifically to understand the concept of Named Entity Recognition across all domains. It isn’t trained to find just people or places; it is trained to identify any entity, preparing it to be fine-tuned on your specific problem with very little data.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the pipeline relies on distillation. The researchers use a massive, smart model (GPT-3.5) to teach a small, efficient model (RoBERTa) via a large intermediate dataset.

Step 1: Creating the Dataset with “Open” Annotation

The biggest bottleneck in training NER models is the lack of diverse, annotated data. Human datasets are usually small and limited to a few types like PER (Person), ORG (Organization), and LOC (Location). To build a truly generalizable NER model, the researchers needed a dataset containing everything.

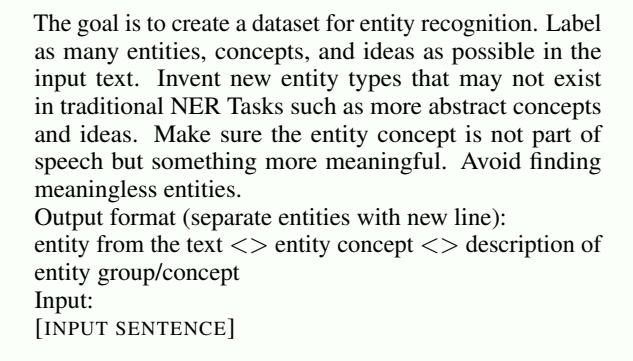

They turned to the C4 corpus (a massive web crawl) and used GPT-3.5 to annotate it. However, they didn’t just ask for standard entities. They used an unconstrained annotation strategy.

As you can see in the prompt (Figure 2), they instructed the LLM to “label as many entities, concepts, and ideas as possible” and to “invent new entity types.” This is crucial. By not restricting the LLM to a predefined list of tags, they captured a rich semantic landscape.

The result is a dataset where GPT-3.5 acts as a high-precision, low-recall teacher. It might miss some entities, but the ones it finds are usually correct and come with descriptive labels.

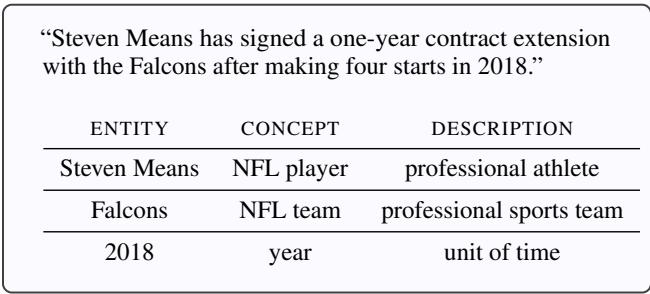

Figure 3 shows an example of this annotation. Note that it identifies “Steven Means” as an NFL player (very specific) and “2018” as a year.

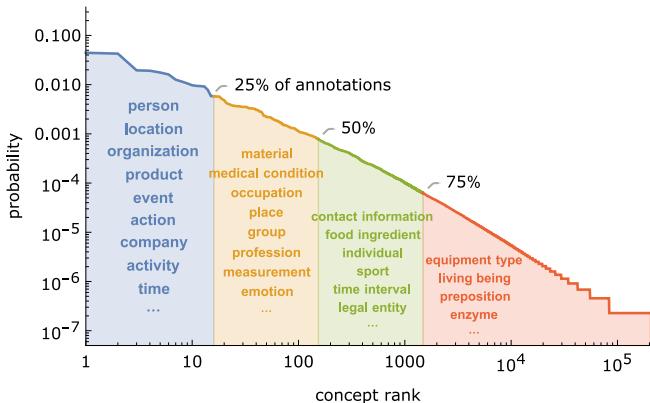

The resulting dataset is massive and incredibly diverse. It contains 4.38 million annotations covering 200,000 unique concept types. This distribution is “heavy-tailed,” meaning there are a few very common concepts (like Person) and thousands of rare, niche concepts.

Step 2: The Core Method - Contrastive Learning

Here lies the main technical innovation of the paper. How do you train a model on 200,000 different entity types?

A standard NER model uses a classification layer (softmax) at the end, where the output dimension equals the number of labels (e.g., 5 tags: B-PER, I-PER, etc.). You cannot have a classification layer with 200,000 outputs; it would be computationally impossible and incredibly sparse.

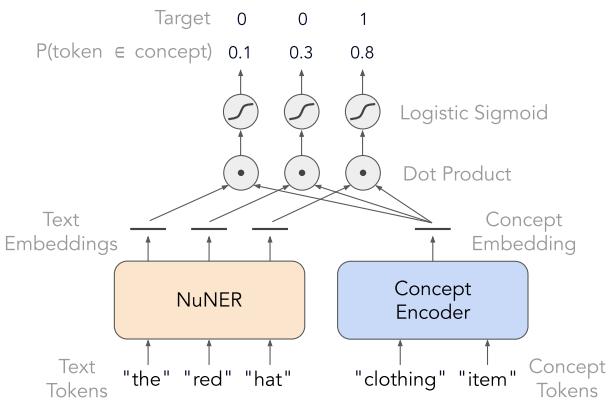

NuNER solves this by treating NER as a similarity problem, not a classification problem. They use an architecture with two separate encoders:

- Text Encoder (NuNER): Takes the sentence and produces a vector for each token.

- Concept Encoder: Takes the name of the concept (e.g., “NFL player”) and produces a single vector.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the model is trained to maximize the similarity (dot product) between the text embedding of a token (like “hat”) and the concept embedding of its label (like “clothing item”).

This Contrastive Learning approach decouples the model from a fixed set of labels. The Text Encoder learns to project tokens into a “semantic space” where entities cluster together based on their meaning.

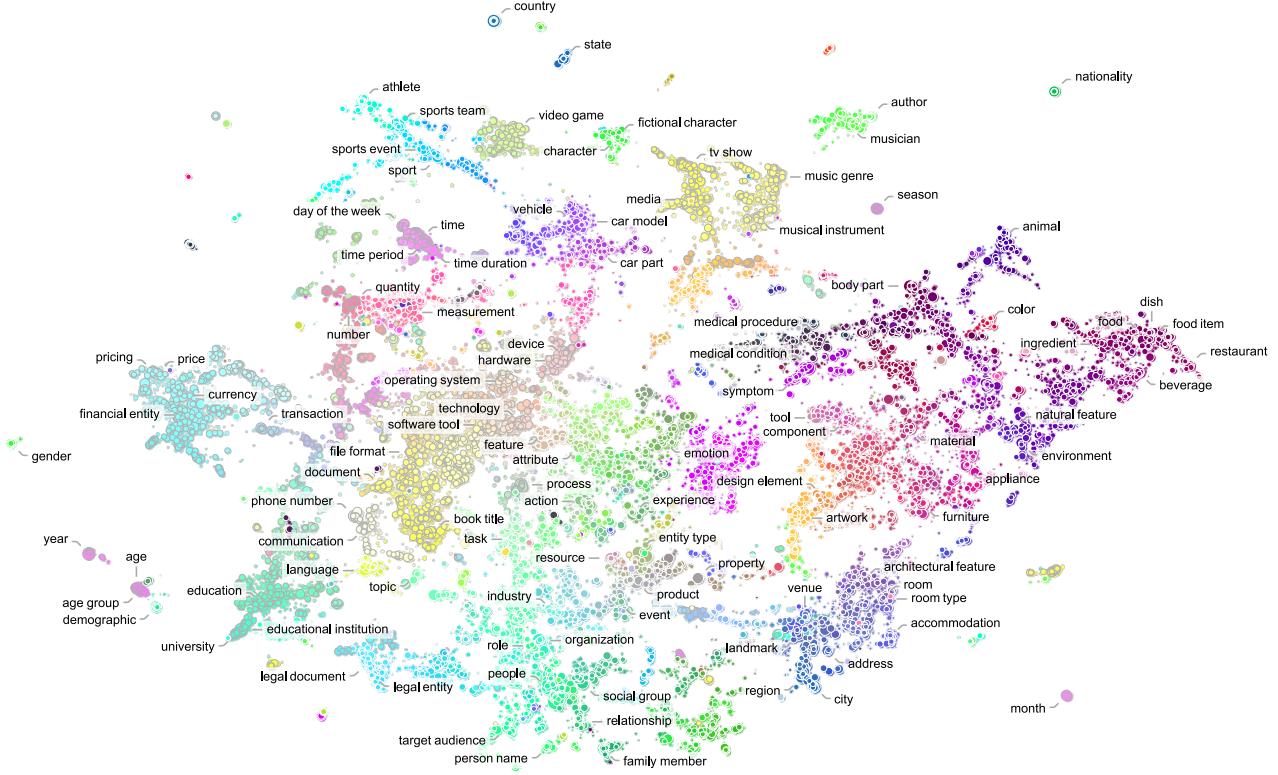

Figure 6 visualizes this learned space. Notice how concepts naturally group together—medical conditions, food items, and vehicles form their own clusters. Because NuNER understands these relationships, fine-tuning it on a specific task (like identifying car parts) becomes much easier. The model already knows that “carburetor” and “piston” are semantically close to “vehicle part.”

Experimental Results: David vs. Goliath

The researchers evaluated NuNER in a few-shot transfer learning setting. This simulates the real-world scenario where a developer has only a handful of examples (10 to 100) for their specific problem.

They compared three models:

- RoBERTa: The standard baseline.

- RoBERTa w/ NER-BERT: A RoBERTa model pre-trained on an older, large NER dataset derived from Wikipedia anchors.

- NuNER: The proposed model.

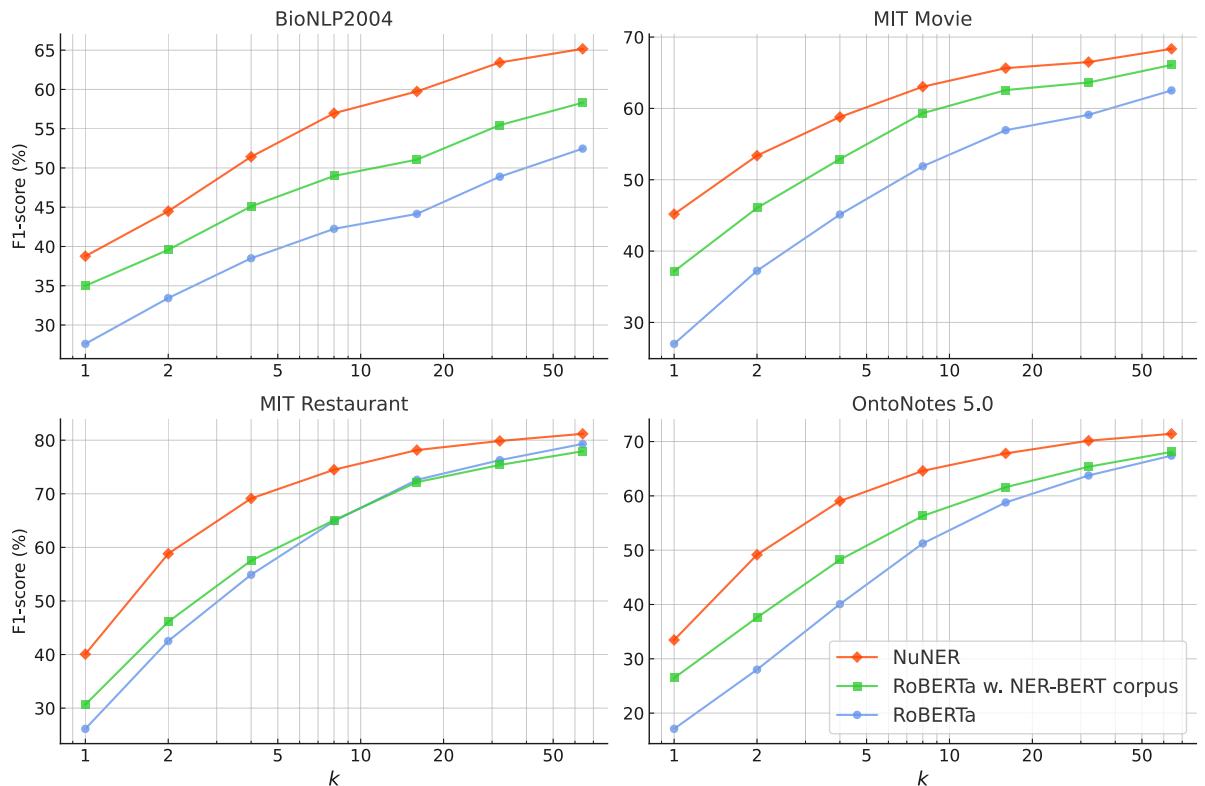

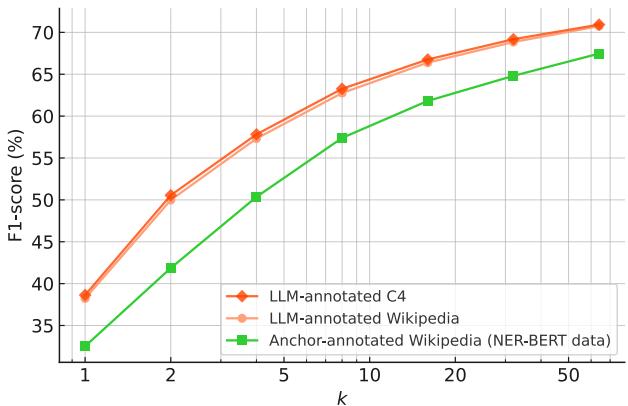

1. Superior Few-Shot Performance

The results were broken down by dataset (BioNLP, MIT Movie, MIT Restaurant, OntoNotes) and by the number of training examples (\(k\)).

NuNER (the orange line in Figure 13) consistently outperforms both the standard RoBERTa and the previous state-of-the-art NER-BERT model across all datasets. The gap is particularly significant when data is scarce (\(k\) is low). This confirms that pre-training on the messy, diverse, LLM-annotated data provides a much stronger foundation than clean but limited Wikipedia data.

2. Rivaling Large Language Models

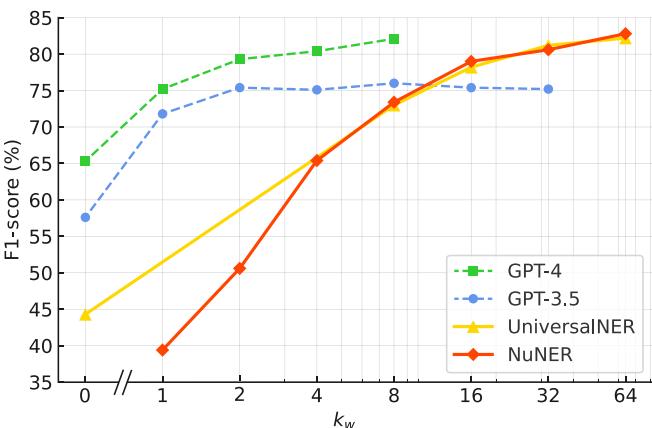

Perhaps the most surprising result is how NuNER stacks up against the very models that helped create it. The researchers compared NuNER (125 Million parameters) against UniversalNER (7 Billion parameters) and GPT-3.5 via prompting.

Figure 12 reveals a fascinating trend:

- Zero-shot: Large models like GPT-4 start strong (high F1 score at \(k=0\)) because they have vast general knowledge. NuNER starts at zero because it requires fine-tuning.

- Few-shot: As soon as you provide about 8 to 16 examples, NuNER catches up. It surpasses GPT-3.5 and matches the performance of UniversalNER.

This is a massive efficiency win. NuNER achieves LLM-level performance with a model that is 56 times smaller than UniversalNER and thousands of times smaller than GPT-3.5, making it suitable for deployment on standard hardware with low latency.

Why Does It Work? (Ablation Studies)

The paper digs into why NuNER works so well. Is it the web text? The number of tags? The size of the data?

It’s Not the Text Source

The researchers compared training on Wikipedia vs. C4 (Web text), holding the annotation method constant.

Figure 8 shows that the lines for C4 and Wikipedia overlap significantly. The underlying text source matters less than the annotations.

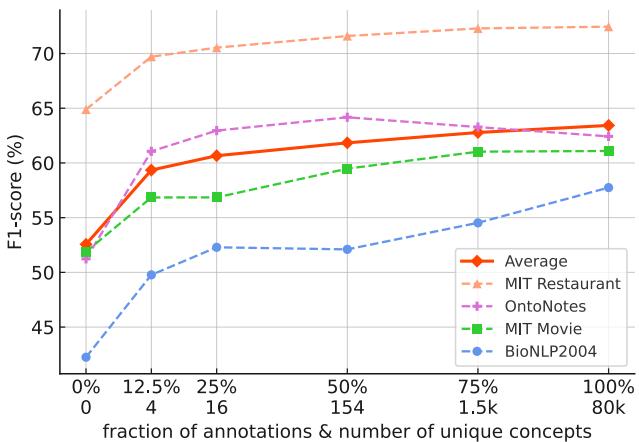

It Is the Concept Diversity

This is the critical finding. The researchers artificially restricted the number of concept types in the pre-training data to see how it affected downstream performance.

As shown in Figure 9, performance drops significantly if the model is only trained on a small set of entity types (the left side of the graph). The model gains its power from seeing thousands of diverse concepts—from “musical instrument” to “molecular structure”—during pre-training. This diversity forces the model to learn a robust, universal representation of what an “entity” looks like in text.

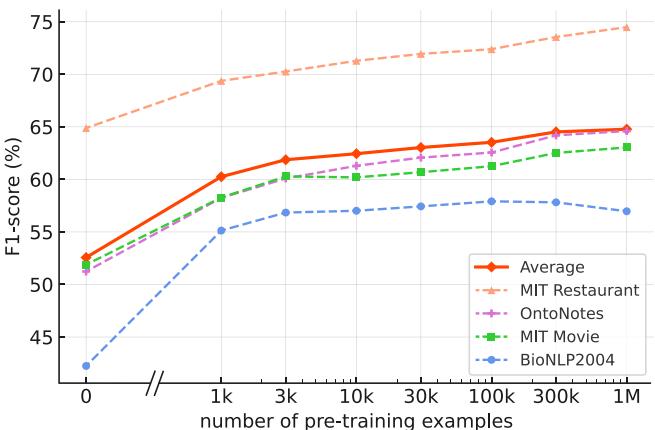

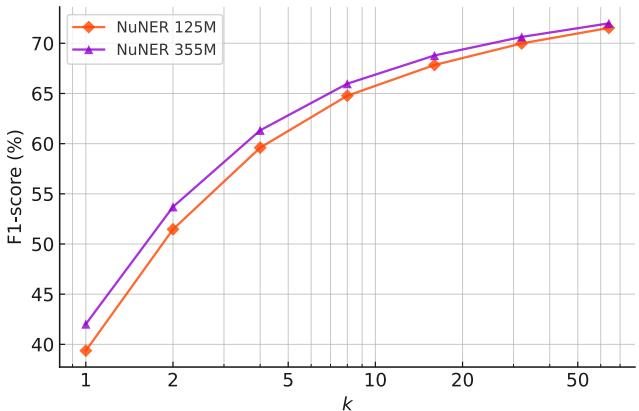

Size Matters (Data and Model)

Naturally, more data helps. Figure 10 (below) shows a logarithmic improvement as the dataset size grows from 1k to 1M examples.

Similarly, scaling the model itself from NuNER-base (125M) to NuNER-large (355M) yields consistent gains, as seen in Figure 11.

Conclusion

NuNER demonstrates a powerful new paradigm in NLP: distillation via annotation. Instead of using LLMs to replace small models, we can use them to empower small models.

By using GPT-3.5 to generate a massive, diverse, noisy dataset and employing contrastive learning to handle the sheer variety of concepts, the authors created a model that punches well above its weight class.

For students and practitioners, the takeaways are clear:

- Data Diversity > Text Quantity: Having 200,000 entity types was more important than the source of the text.

- Architecture Matters: The switch from Softmax classification to Contrastive Learning allowed the model to learn from an open-ended label set.

- Efficiency: You don’t always need a 70B parameter model. A specialized 100M parameter model, pre-trained correctly, can deliver SOTA results at a fraction of the cost.

NuNER paves the way for a family of “Task-Specific Foundation Models”—not just for NER, but potentially for sentiment analysis, summarization, and beyond.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.15343/images/cover.png)