If you have played with recent Large Vision-Language Models (LVLMs) like GPT-4V, LLaVA, or InstructBLIP, you’ve likely been impressed. You can upload a photo of a messy room and ask, “What’s on the table?” or upload a meme and ask, “Why is this funny?” and the model usually responds with eerie accuracy. These models have bridged the gap between pixels and text, allowing for high-level reasoning and captioning.

However, there is a catch. While these models are excellent generalists, they are surprisingly poor specialists. If you upload a photo of a bird and ask, “Is this a bird?”, the model says yes. But if you ask, “Is this a Cerulean Warbler or a Black-throated Blue Warbler?”, the model often falls apart.

This specific challenge is known as Fine-Grained Visual Categorization (FGVC). A recent paper titled “Finer: Investigating and Enhancing Fine-Grained Visual Concept Recognition in Large Vision Language Models” investigates this phenomenon. The researchers uncover a significant “modality gap” in state-of-the-art models and propose a novel benchmarking and training strategy to fix it.

In this post, we will tear down their research to understand why powerful AI models fail at details and how we can teach them to see better.

The Illusion of Competence

To understand the problem, we first need to look at how these models are typically evaluated. Most benchmarks test for general understanding: describing a scene, reading text in an image (OCR), or answering logical questions.

However, scientific and real-world applications often require precise identification. A biologist doesn’t just see a “plant”; they see a " Monstera deliciosa." A car enthusiast doesn’t just see a “sedan”; they see a “2018 Hyundai Santa Fe.”

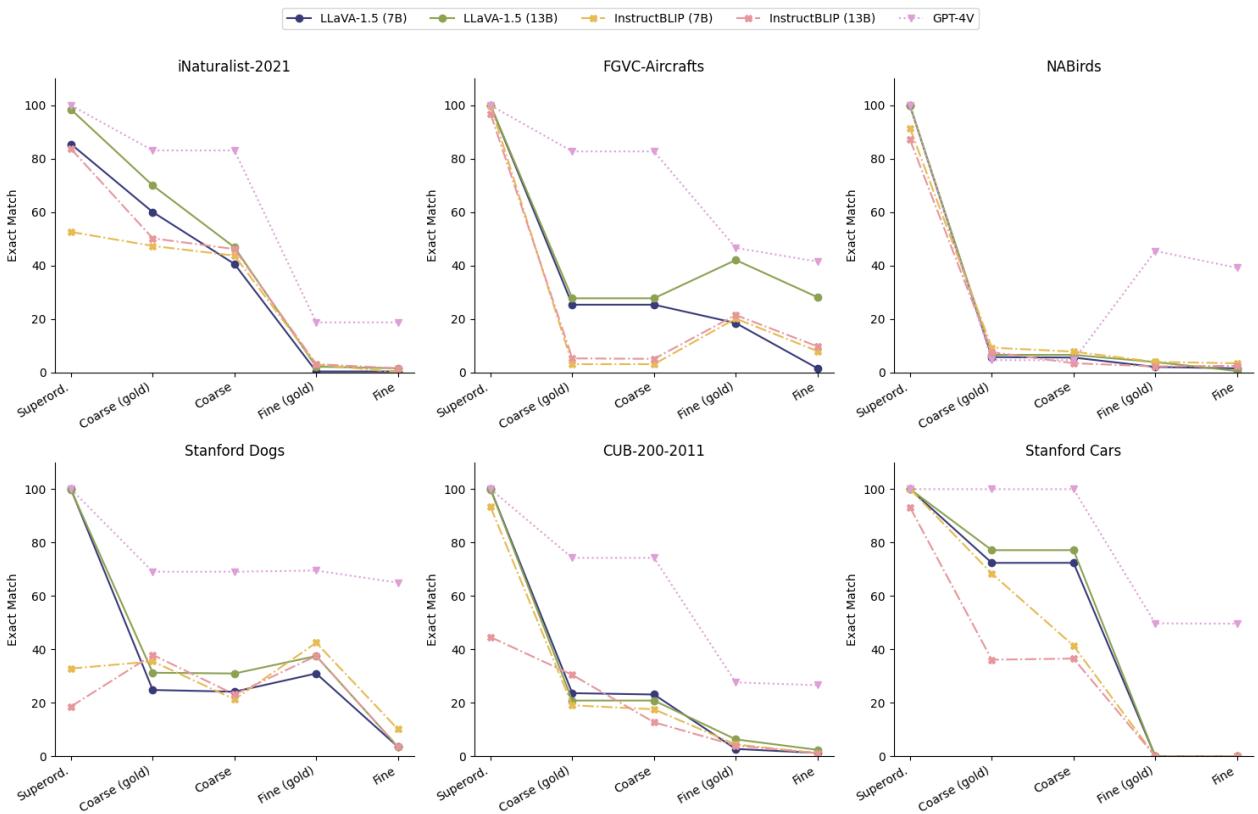

The researchers tested five major models (including LLaVA, InstructBLIP, and GPT-4V) across six fine-grained datasets involving birds, dogs, cars, and aircraft. The results were stark.

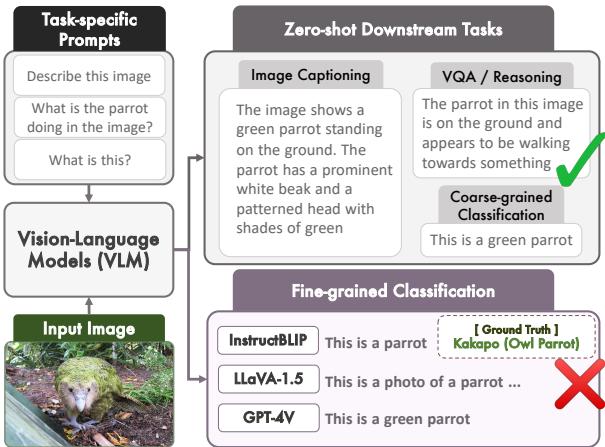

As shown in Figure 1 above, models like LLaVA are fantastic at generating a paragraph describing a parrot. But when asked to perform the classification task—identifying the specific breed or species—they often hallucinate or revert to generic answers.

The Performance Cliff

The paper quantifies this failure using a metric called “Exact Match” (EM), which checks if the model can generate the correct specific class name. The researchers divided labels into three tiers:

- Superordinate: High-level categories (e.g., “Bird”).

- Coarse: Mid-level categories (e.g., “Owl”).

- Fine: Specific categories (e.g., “Great Horned Owl”).

Figure 2 illustrates a dramatic “performance cliff.” Look at the blue line (LLaVA-1.5 7B) on the first graph (iNaturalist-2021). The model achieves nearly 100% accuracy on superordinate categories. It drops to around 40% for coarse categories. But for fine-grained categories? It plummets to nearly 0%.

Even GPT-4V (the purple dotted line), which is currently considered the state-of-the-art, sees a significant drop in accuracy as the task moves from coarse to fine recognition.

Diagnosing the “Modality Gap”

Why does this happen? Is it because the Large Language Model (LLM) inside these architectures doesn’t know what a “Cerulean Warbler” is?

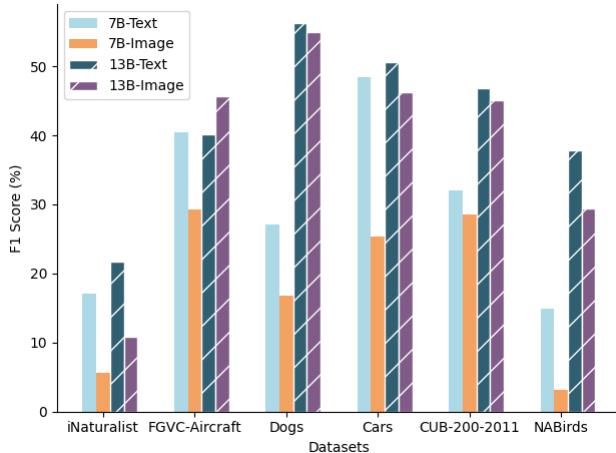

To find out, the researchers conducted a fascinating “Knowledge Probing” experiment. They tested the models in two different ways:

- Image-only: Showing the model the photo and asking for the species.

- Text-only: Providing the model with a textual list of visual attributes (e.g., “blue upper parts,” “white belly,” “black necklace”) and asking for the species.

The results in Figure 4 are revealing. When LLaVA-1.5 (7B) is given text descriptions (the light blue bars), its accuracy is significantly higher than when it looks at the image (the orange bars).

This confirms a critical hypothesis: The model has the knowledge. The LLM component has read the entire internet; it knows the taxonomy of birds and cars. The failure lies in the Modality Gap. The visual encoder (the “eyes”) fails to extract the specific details needed to trigger the correct knowledge in the LLM (the “brain”).

Information Loss in Translation

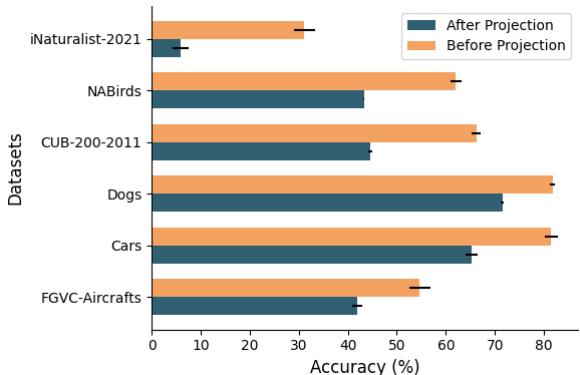

Most LVLMs use a vision encoder (like CLIP) to turn an image into numbers (embeddings), and then a “projection layer” to translate those numbers into the language space the LLM understands.

The researchers discovered that this projection process is “lossy.”

As shown in Figure 5, the researchers performed linear probing—training a simple classifier on the data—both before and after the projection layer. The orange bars represent the raw visual data from the encoder, while the dark teal bars represent the data after it has been projected for the LLM.

In every dataset, accuracy drops after projection. The translation from “vision language” to “text language” smooths over the sharp, fine-grained details necessary for distinction. The model essentially puts on foggy glasses before trying to read the fine print.

The Solution: FINER and ATTRSEEK

Identifying the problem is only half the battle. The researchers propose a solution centered on the idea that if the model is skipping over details, we must force it to look closer.

They introduce FINER, a new benchmark and training mixture, and ATTRSEEK, a prompting strategy.

1. The FINER Benchmark

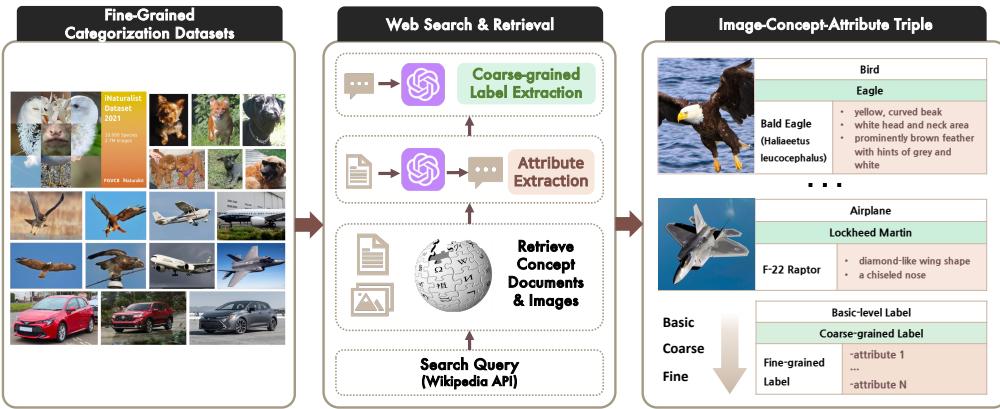

To train models to notice details, you need data that emphasizes details. The researchers constructed the FINER dataset by aggregating six existing fine-grained datasets (like CUB-200 for birds and Stanford Cars) and enhancing them with rich textual attributes extracted from Wikipedia.

As Figure 6 shows, they didn’t just grab labels; they used GPT-4V to extract “concept-indicative attributes.” For a Bald Eagle, the dataset includes structured data about its yellow beak, white head, and dark brown body. This creates a bridge: it links the visual concept not just to a name (label), but to a description (attributes).

2. The ATTRSEEK Pipeline

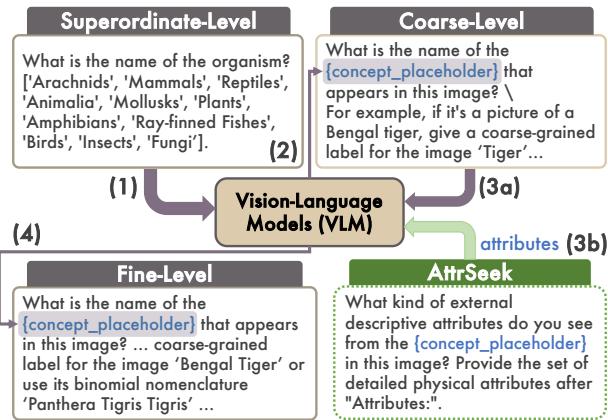

With this attribute-rich data, the researchers developed a new inference method called ATTRSEEK (Attribute Seeking).

Standard prompting asks: “What bird is this?” ATTRSEEK asks: “What visual attributes do you see?” \(\rightarrow\) “Based on those attributes, what bird is this?”

This process, illustrated in Figure 3, forces the model to verbalize the visual evidence before making a conclusion. It mimics how a human expert works: first observing the wing bars and beak shape, and then consulting their mental field guide.

Does It Work?

The results indicate that explicitly modeling attributes helps bridge the modality gap.

Qualitative Analysis

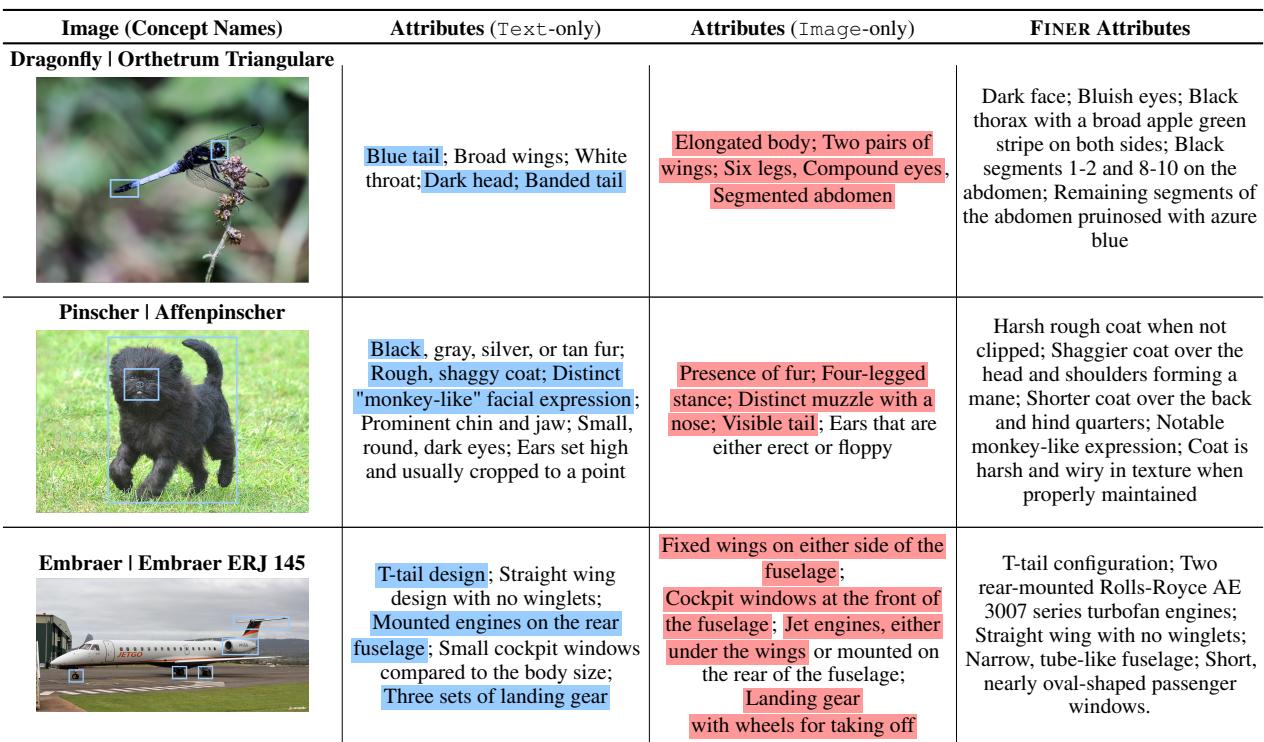

First, let’s look at what the models actually “see.” The researchers compared the attributes generated by a standard model (Image-only) versus the actual distinct attributes defined in the FINER dataset (Text-only reference).

In Table 3 (shown above), look at the example of the Dragonfly (Orthetrum Triangulare).

- Image-only (Standard VLM): Sees “Elongated body,” “Two pairs of wings,” “Compound eyes.” These are correct, but they are generic. They describe every dragonfly.

- FINER Attributes: Describes “Black thorax with a broad apple green stripe,” “Blue tail.” These are specific.

When the model is forced to look for these specific attributes via ATTRSEEK, it hallucinates less and grounds its reasoning in the actual pixel data.

Quantitative Improvements

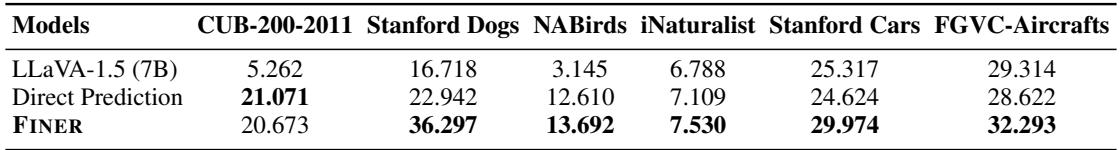

When LLaVA-1.5 was fine-tuned on the FINER training mixture (teaching it to look for attributes), the zero-shot performance on fine-grained tasks improved significantly.

Table 4 highlights the gains. “Direct Prediction” is the standard way of training a model (Image \(\to\) Label). “FINER” is the new method (Image \(\to\) Attributes \(\to\) Label).

- On Stanford Dogs, performance jumped from 22.9% to 36.3%.

- On Stanford Cars, it rose from 24.6% to 30.0%.

By teaching the model to articulate why it thinks an image is a specific class, the researchers effectively reduced the information loss identified earlier.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The paper “Finer” sheds light on a critical blind spot in modern AI. While we are dazzled by the conversational abilities of Vision-Language Models, they often lack the “visual acuity” to handle specialized tasks.

Here are the key takeaways for students and practitioners:

- The Modality Gap is Real: Just because an LLM knows a fact doesn’t mean the Vision Encoder can trigger that fact. There is a disconnect between textual knowledge and visual representation.

- Projection is Lossy: The architectural layer that translates images to text embeddings simplifies the image, often discarding the fine-grained texture and pattern information needed for expert identification.

- Prompting Matters: Techniques like ATTRSEEK prove that we can improve performance without changing the model architecture simply by changing the process. Forcing a model to “show its work” (describe attributes) before answering acts as a form of error correction.

- Data Quality: The FINER benchmark demonstrates that for higher-level AI performance, we need datasets that go beyond simple

(Image, Label)pairs. We need(Image, Attributes, Label)triples to teach models the nuance of the real world.

As we move toward more autonomous AI agents, fine-grained understanding will be essential. A robot pharmacist needs to distinguish between two similar-looking pills; an agricultural drone needs to distinguish between a crop and a weed. Research like Finer provides the roadmap for getting us there.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.16315/images/cover.png)