Introduction: The Quality vs. Quantity Dilemma

In the current landscape of Large Language Model (LLM) development, there is a prevailing assumption that “more is better.” We often assume that to make a model smarter, we must feed it more tokens, more documents, and more instructions. This is generally true for the pre-training phase, where models learn the statistical structure of language. However, the rules change significantly during the Instruction Tuning (IT) phase—the final polish that teaches a model to act as a helpful assistant.

During instruction tuning, the quality of data often matters far more than the sheer volume. Recent research, such as the LIMA paper, demonstrated that a model fine-tuned on just 1,000 carefully curated examples could outperform models trained on 50,000 noisy ones. But here lies the bottleneck: creating those 1,000 “golden” examples usually requires expensive human annotation.

Ideally, we would automate this. We would take a massive, noisy dataset (like Alpaca-52k) and algorithmically filter it down to the best 2%. Previous attempts, such as Alpagasus, tried to do this using GPT-3.5 as a judge. While efficient, this approach introduces a “machine bias”—LLMs tend to favor verbose answers or answers that sound like themselves, rather than what a human expert would actually prefer.

Enter the Clustering and Ranking (CaR) method. In a fascinating new paper, researchers propose an industrial-friendly approach that selects high-quality instruction data by aligning with human experts rather than just other AI models. By combining a quality scoring mechanism with a diversity-preserving clustering algorithm, they managed to use less than 2% of the original Alpaca dataset to train a model—AlpaCaR—that significantly outperforms the original.

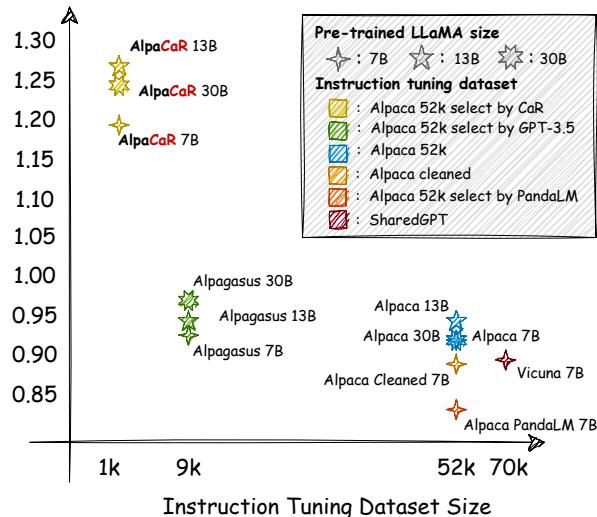

As shown in Figure 1 above, AlpaCaR achieves superior performance across multiple benchmarks (Vicuna, Self-Instruct, etc.) despite using a tiny fraction of the training data. In this post, we will dissect how CaR works, why diversity is the secret ingredient to small-data training, and how you can achieve state-of-the-art results with a fraction of the computational budget.

Background: The Instruction Tuning Landscape

Before diving into the method, let’s establish the context. Instruction Tuning is the process of taking a pre-trained base model (like LLaMA) and fine-tuning it on pairs of (Instruction, Output).

The community was revolutionized by the release of the Alpaca dataset, which used the “Self-Instruct” method. Essentially, they asked a powerful model (GPT-3/text-davinci-003) to generate 52,000 instruction-response pairs. This was a breakthrough because it was cheap and fast. However, machine-generated data is noisy. It contains errors, hallucinations, and repetitive tasks.

The Problem with Existing Filtering Methods

Naturally, researchers began trying to filter this data. The most common method is LLM-as-a-Judge. You simply ask a strong model (like GPT-4) to rate the quality of the training pairs and keep the top ones.

However, the authors of the CaR paper identify two critical flaws in this standard approach:

- Systematic Bias: GPT models exhibit “self-enhancement bias.” They prefer outputs that sound like them. GPT-4 might rate a GPT-3 generated response highly just because of stylistic similarities, even if the factual content is mediocre. Furthermore, they suffer from “verbosity bias,” preferring longer answers even if they are fluff.

- Loss of Diversity: If you simply rank 52,000 instructions by a quality score and take the top 1,000, you might end up with 1,000 creative writing prompts and zero math problems. High-quality data is useless if it doesn’t cover the breadth of tasks an LLM needs to perform.

The CaR framework was designed specifically to solve these two problems: getting an expert opinion on quality and ensuring the dataset remains diverse.

Core Method: Clustering and Ranking (CaR)

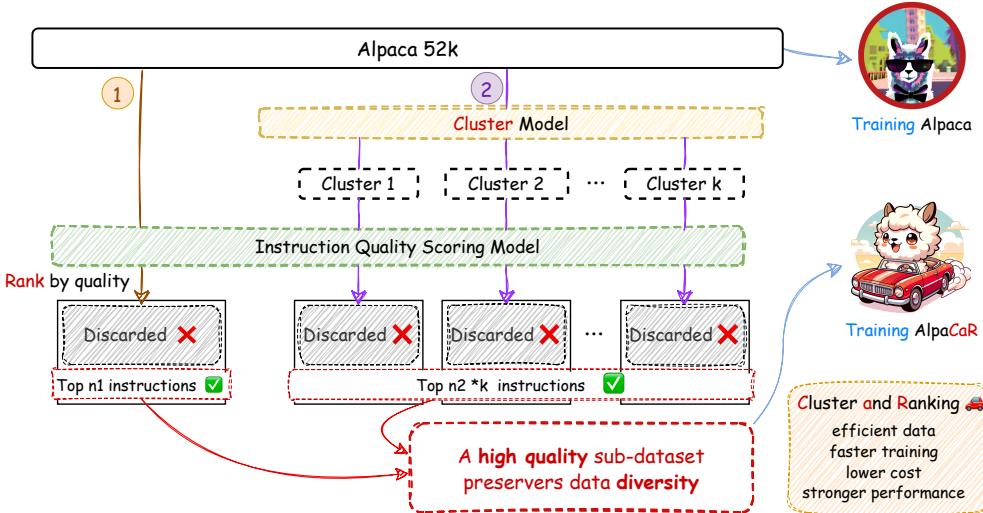

The CaR method is an elegant, two-step pipeline. The goal is to filter a large, noisy dataset (like Alpaca-52k) down to a “high-quality sub-dataset” used to train the final model.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the process flows as follows:

- Ranking (Quality Estimation): A specialized model scores every instruction pair in the dataset.

- Clustering (Diversity Preservation): The instructions are grouped into clusters based on their semantic meaning.

- Selection: The system selects the absolute best instructions (\(n_1\)) and the best instructions from each cluster (\(n_2\)).

- Training: These selected instructions form the new dataset for AlpaCaR.

Let’s break down these components in detail.

Step 1: Expert-Aligned Quality Estimation (IQE)

The first challenge is figuring out which instructions are “good.” Instead of relying on a generic GPT-4 prompt, the researchers introduced a new concept: Instruction Pair Quality Estimation (IQE).

They trained a specific, lightweight model (550M parameters) called the Instruction Quality Scoring (IQS) model. The key differentiator here is the training data. They used a dataset where linguistic experts manually revised Alpaca instructions to improve fluency, accuracy, and coherence.

This allowed the model to learn a specific boundary: What does a human expert prefer over a raw GPT generation?

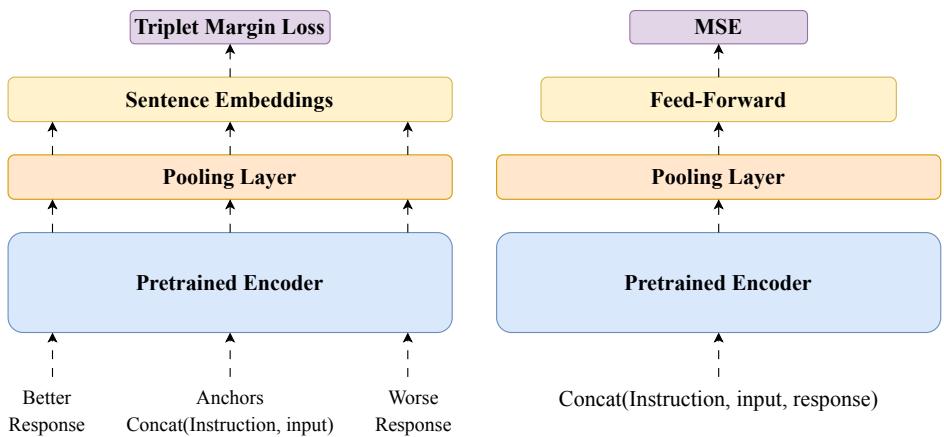

The IQS Architecture

To build the IQS model, the researchers adapted the Comet framework, widely used in Machine Translation evaluation. They experimented with two architectures.

- Comet-Instruct (Left in Figure 10): This uses a triplet loss. It looks at an instruction and compares a “better” response against a “worse” response, trying to minimize the distance to the good one. While effective (72.44% accuracy), it wasn’t the best they could do.

- IQS Model (Right in Figure 10): This simpler architecture proved more effective. It takes the instruction and the response, concatenates them, and passes them through a pre-trained encoder (XLM-RoBERTa). A regression head then predicts a direct quality score.

This small IQS model achieved an accuracy of 84.25% in aligning with expert preferences, significantly outperforming GPT-4 (63.19%) on the test set. This is a crucial finding: A small, specialized model trained on human expert data can judge quality better than a massive, general-purpose LLM.

Step 2: Preserving Diversity through Clustering

Once every instruction has a quality score, we could just pick the top 1,000. But as mentioned earlier, this kills diversity. To solve this, the researchers used \(k\)-Means Clustering.

They embedded all 52,000 instructions into vector space using a sentence-transformer. Instructions that are semantically similar (e.g., Python coding questions) cluster together in space, while distinct tasks (e.g., writing a poem) form their own clusters.

They determined the optimal number of clusters (\(k\)) using a heuristic based on the dataset size, resulting in 161 distinct clusters for the Alpaca dataset.

Step 3: The Hybrid Selection Strategy

This is where the “Clustering and Ranking” name comes to life. The final selection logic combines global quality with local diversity.

The algorithm selects data in two sweeps:

- Top \(n_1\) Global: Select the top \(n_1\) highest-scoring instructions from the whole dataset. This ensures the absolute highest quality data is included, regardless of topic.

- Top \(n_2\) per Cluster: From each of the \(k\) clusters, select the top \(n_2\) highest-scoring instructions. This ensures that every single topic/task type is represented in the final dataset.

The final dataset size is roughly \(n_1 + (k \times n_2)\). In their primary experiments, they found that a very small dataset was sufficient: roughly 1,000 instructions total.

Experiments and Results

The researchers compared their AlpaCaR model (trained on the subset) against several baselines:

- Alpaca: Trained on the full 52k dataset.

- Alpaca-Cleaned: A community effort to manually clean the dataset.

- Alpagasus: The previous state-of-the-art that used GPT-3.5 filtering.

- Vicuna: A strong baseline trained on ChatGPT conversations.

Main Performance Comparison

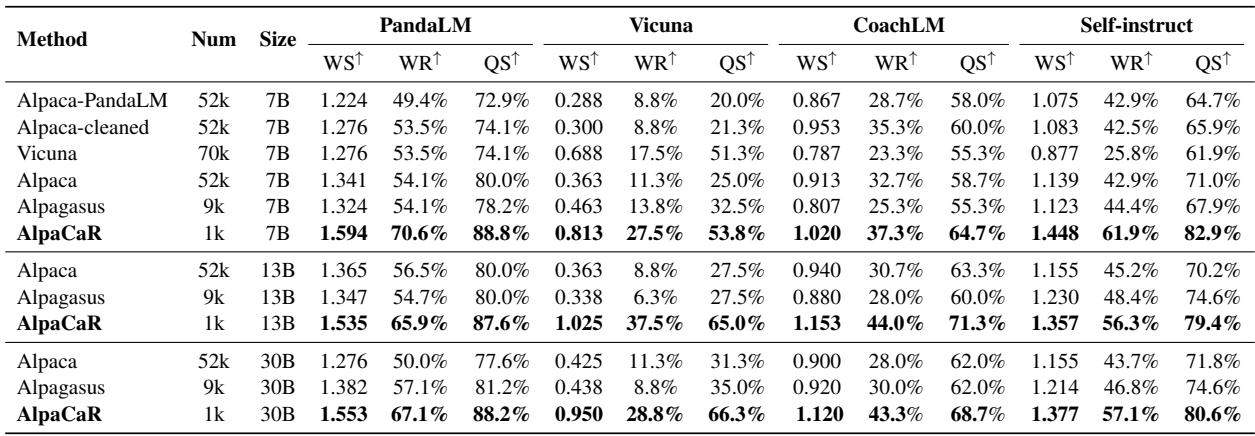

The results were evaluated using “Winning Score” (WS) against reference responses, judged by PandaLM and GPT-4.

Table 2 presents the definitive results. At the 7B parameter scale:

- Alpaca (52k data): WS of 1.341.

- Alpagasus (9k data): WS of 1.324.

- AlpaCaR (1k data): WS of 1.594.

AlpaCaR, using only ~2% of the data (1k samples), massively outperformed the model trained on the full dataset. It even scaled effectively to 13B and 30B parameter models, consistently beating the baselines. This confirms the hypothesis that a small amount of expert-aligned data is far more potent than a large amount of noisy data.

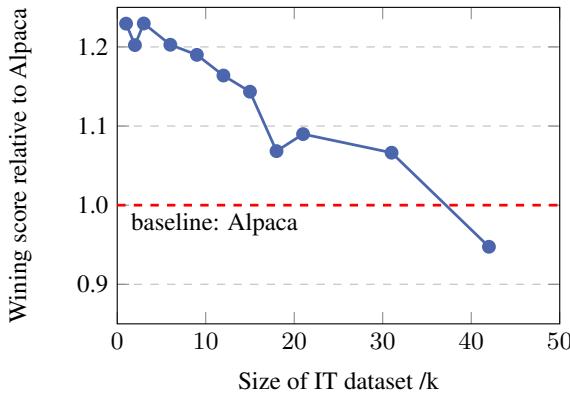

Why Quality Matters (Ablation Study)

The researchers tested what happens if you increase the dataset size by including lower-ranked instructions.

Figure 4 illustrates a counter-intuitive phenomenon. As they added more data (moving from 1k to 50k on the x-axis), the model’s performance (y-axis) actually decreased. The curve starts high at 1k and steadily drops below the baseline. This is strong evidence that the “long tail” of the Alpaca dataset is not just useless—it is actively harmful to the model’s performance.

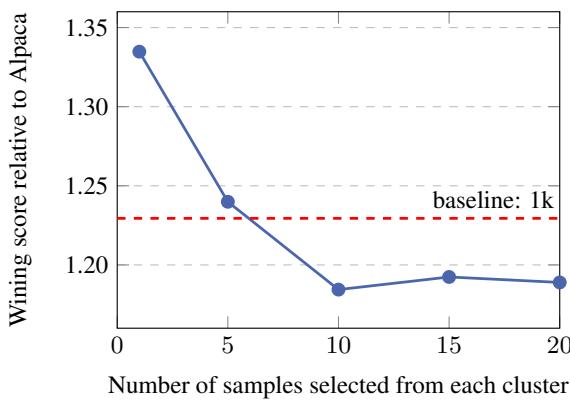

Why Diversity Matters (Ablation Study)

Is it enough to just pick the high scores? The researchers tested varying the parameter \(n_2\) (the number of samples picked from each cluster).

Figure 5 shows that picking just one high-quality sample from each cluster (\(n_2=1\)) provided the best performance boost. Increasing the samples per cluster (\(n_2=5, 10, 20\)) caused performance to dip. This suggests that LLMs are very efficient learners; they only need one or two strong examples of a specific task type (like “write a haiku”) to learn the skill. Feeding them 20 variations of the same task yields diminishing returns and potential overfitting.

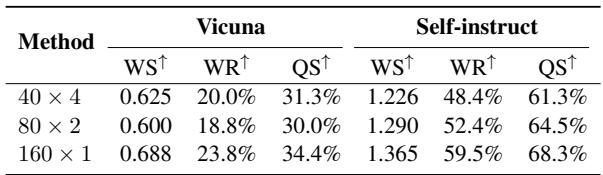

The table below further cements the importance of diversity:

Table 3 compares selection strategies. The strategy \(160 \times 1\) (picking 1 example from 160 different clusters) significantly outperforms \(40 \times 4\) (picking 4 examples from only 40 clusters). Broad task coverage is essential.

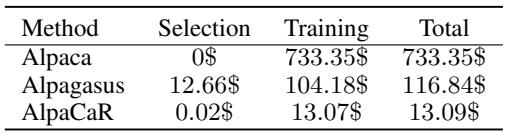

Cost Efficiency

One of the most compelling arguments for CaR is the cost. Training LLMs is expensive, and reducing the dataset size by 98% has a massive impact on the budget.

Table 6 breaks down the costs for the 30B model scale.

- Alpaca: $733 to train.

- Alpagasus: $116 (including API costs for filtering).

- AlpaCaR: $13.09.

The CaR method reduces the financial outlay to just 11.2% of existing filtering methods and a tiny fraction of full training. For students or small startups, this makes training high-performance 30B models actually accessible.

Analysis: Human vs. GPT Evaluation

Evaluation of LLMs is notoriously difficult. To ensure their results weren’t just an artifact of one specific judge, the researchers used multiple evaluation methods.

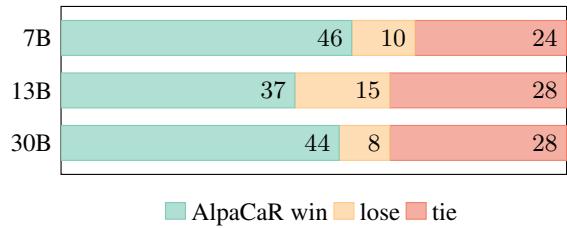

GPT-4 Evaluation

They ran head-to-head comparisons using GPT-4.

Figure 7 shows AlpaCaR (teal) winning significantly more often than it loses against the baseline Alpaca model across 7B, 13B, and 30B sizes on the Vicuna benchmark.

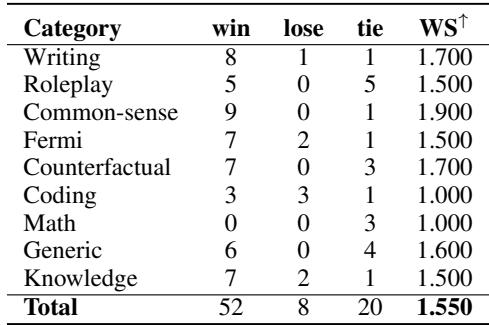

Human Expert Evaluation

Perhaps most importantly, they employed human language experts to blindly review the outputs.

Table 4 shows the human evaluation on the 30B models. AlpaCaR won 52 times compared to Alpaca’s 8 wins. This is a landslide victory, particularly in categories like “Common-sense,” “Knowledge,” and “Writing.”

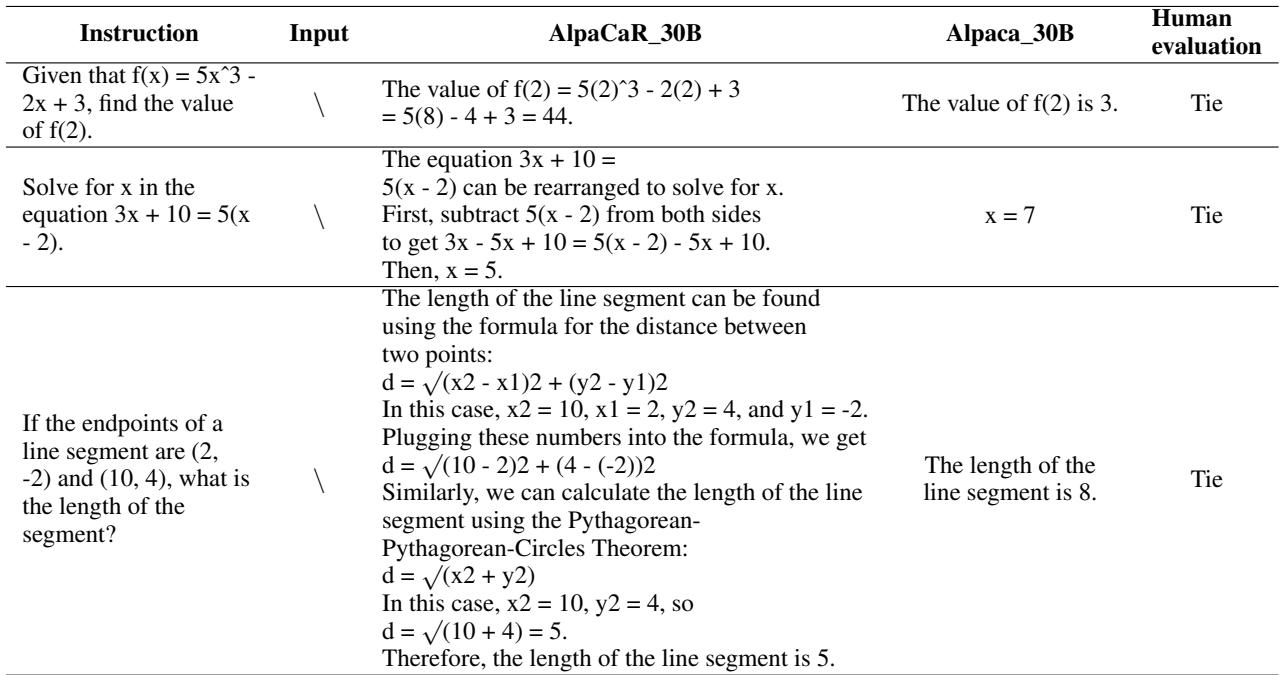

Case Study: Reasoning vs. Hallucination

A qualitative look at the outputs reveals why AlpaCaR scores better.

In the math example shown in Table 7, the model is asked to find the value of a function.

- Alpaca: Simply guesses “The value of f(2) is 3.” (Incorrect and provides no working).

- AlpaCaR: Attempts a step-by-step derivation. While the experts marked it as a “Tie” (likely due to a minor calculation error or strict grading), AlpaCaR demonstrated Chain of Thought (CoT) reasoning. It understood how to solve the problem, whereas Alpaca treated it as a simple retrieval task. This behavior suggests that the IQS model successfully prioritized instructions that contained logical reasoning steps, transferring that capability to the final model.

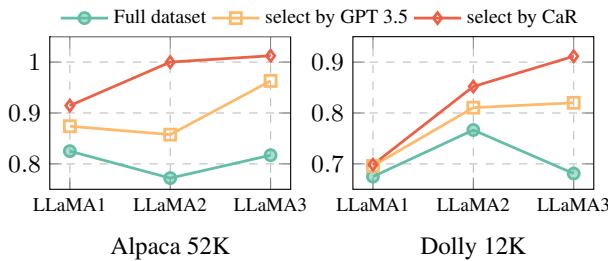

Generalization: Does this hold for LLaMA 2 and 3?

A common critique in AI research is that methods developed for older models (like LLaMA 1) might not work on newer, stronger base models. The researchers addressed this by testing CaR on LLaMA 2 and LLaMA 3.

Figure 8 (Left) shows the results on LLaMA 1, 2, and 3. The red line (CaR) consistently sits above the teal line (Full Dataset). This proves that data selection is a consistent paradigm. Even as base models get smarter (trained on trillions more tokens), they still benefit from a curated, high-quality, diverse fine-tuning dataset rather than a massive noisy one.

Interestingly, they found that LLaMA 3 was arguably more sensitive to data quality, showing a sharper performance drop when trained on the full, noisy dataset compared to the curated CaR subset.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Clustering and Ranking” (CaR) paper offers a compelling narrative shift for the LLM community. We are moving away from the era of “big data” and into the era of “smart data.”

Key Takeaways:

- Experts over Algorithms: A small scoring model trained on expert data is more effective at judging quality than a massive generic model like GPT-4.

- Diversity is Non-Negotiable: You cannot simply pick the “best” data; you must pick the “best of every kind” of data. Clustering provides an unsupervised, scalable way to do this.

- Efficiency: You can achieve State-of-the-Art (SOTA) performance with ~2% of the standard training data, reducing costs by nearly 90%.

For students and researchers, this is empowering. It means you don’t need a cluster of H100 GPUs to train a competitive model. You need a clever selection algorithm and a focus on data quality. As models continue to scale, the ability to discern the “golden needles” in the data haystack will likely become the most valuable skill in the field of AI engineering.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2402.18191/images/cover.png)