Imagine a virtual town populated entirely by AI agents. They wake up, go to work, gossip at the coffee shop, and negotiate prices at the market. It sounds like science fiction—specifically, like Westworld or The Sims powered by supercomputers—but recent advances in Large Language Models (LLMs) have brought us tantalizingly close to this reality.

Researchers and developers are increasingly using LLMs to simulate complex social interactions. These simulations are used for everything from training customer service bots to modeling economic theories and testing social science hypotheses. The assumption is simple: if an LLM can write a convincing dialogue between two people, it can simulate a society.

But a new research paper titled “Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy? The Misleading Success of Simulating Social Interactions With LLMs” throws a bucket of cold water on this enthusiasm. The researchers argue that our current methods for simulating society are fundamentally flawed. They rely on an “omniscient” perspective that creates a fantasy of social competence—a fantasy that collapses when you force AI agents to behave like real humans with limited information.

In this deep dive, we will unpack this paper to understand why simulating social interaction is harder than it looks, why “God Mode” is cheating, and what happens when AI agents are forced to navigate the messy reality of Information Asymmetry.

The Core Problem: Information Asymmetry

To understand the paper’s central thesis, we first need to understand a concept called Information Asymmetry.

In the real world, social interaction is defined by what we don’t know. When you negotiate a salary, you don’t know the absolute maximum the boss is willing to pay. When you go on a first date, you don’t know if the other person loves or hates Star Wars. You have your private thoughts, goals, and secrets; they have theirs. The conversation is the bridge we build to uncover that information.

This is the “Non-Omniscient” setting. It requires Theory of Mind—the ability to attribute mental states to others and understand that their beliefs and knowledge are different from your own.

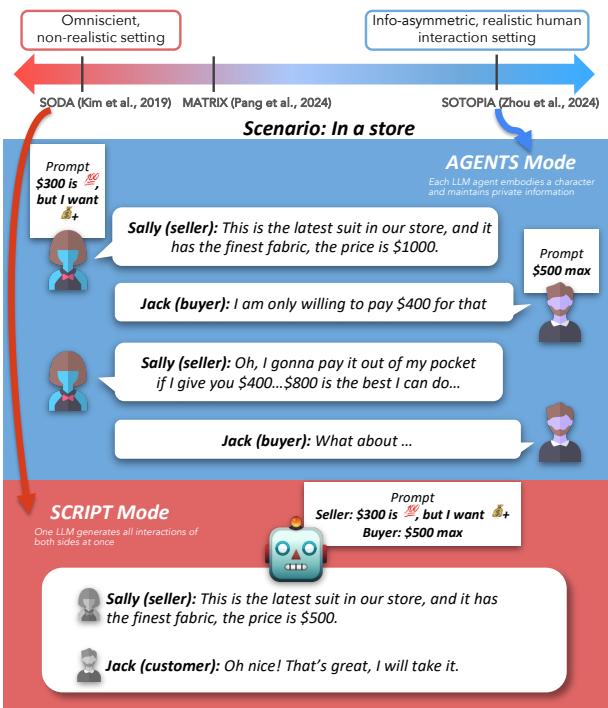

However, most current LLM simulations cheat. They utilize what the researchers call a SCRIPT mode. In this mode, a single, powerful LLM generates the dialogue for both sides of the conversation simultaneously. Because one model controls everything, it knows everyone’s secrets, goals, and constraints instantly. It effectively plays “God” with the characters.

The researchers set out to answer a critical question: Does the success of these omniscient SCRIPT simulations translate to realistic, agent-based interactions?

The Framework: SCRIPT vs. AGENTS

To test this, the authors developed a unified simulation framework based on Sotopia, an environment designed to evaluate social intelligence. They set up three distinct modes of simulation to compare performance.

1. SCRIPT Mode ( The Fantasy)

In this setting, a single LLM acts as a playwright. It is given the full profiles, goals, and secrets of two characters (let’s call them Sally and Jack) and is asked to write a script of their interaction. The model is omniscient; it suffers from zero information asymmetry.

2. AGENTS Mode (The Real Life)

This is the realistic setting. Two separate LLM instances are instantiated.

- Agent A plays Sally. It only knows Sally’s goals and background.

- Agent B plays Jack. It only knows Jack’s goals and background. They must communicate, turn-by-turn, to achieve their goals without knowing what the other person is thinking. This mimics real human interaction.

3. MINDREADERS Mode (The Control)

This is a hybrid ablation study. The setup is the same as AGENTS (two separate models), but the researchers artificially remove the information asymmetry. They give Sally’s model full access to Jack’s secrets and goals, and vice versa. They are separate agents, but they are telepathic.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the difference is stark. In the AGENTS mode (Blue), the buyer and seller have private price limits ($300 vs $500). They have to haggle, and the negotiation is messy. In the SCRIPT mode (Red), the single model sees both limits immediately and simply generates a dialogue where they agree on $500, bypassing the struggle of negotiation.

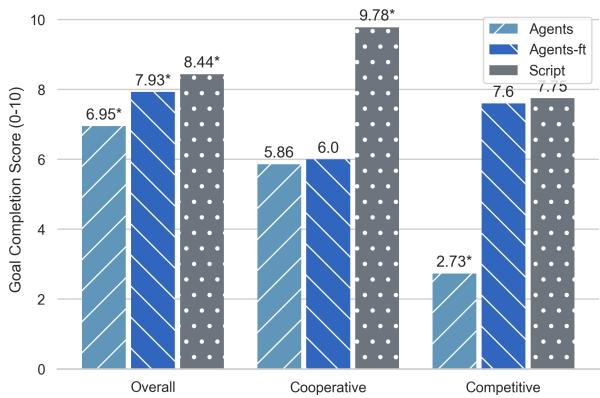

Experiment 1: The Competence Gap

The first major finding of the paper is that LLMs are significantly worse at achieving social goals when they don’t have omniscient knowledge.

The researchers evaluated the simulations using a Goal Completion Score (scaled 0-10). They looked at various scenarios, specifically focusing on:

- Cooperative Scenarios: e.g., “Mutual Friends,” where two strangers try to figure out if they know the same person.

- Competitive Scenarios: e.g., “Craigslist,” where a buyer and seller haggle over a price.

The Results

The data shows a massive discrepancy between the fantasy of the SCRIPT and the reality of the AGENTS.

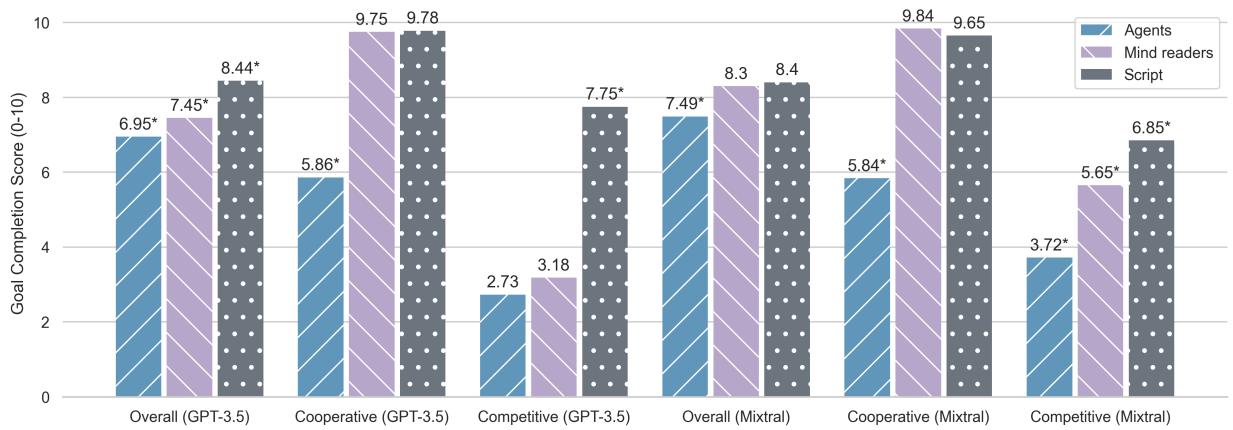

Looking at Figure 2, we can draw several conclusions:

- SCRIPT is Easy Mode: The grey bars (Script) consistently show high goal completion scores (over 8/10). When one model controls the universe, it ensures the characters succeed.

- AGENTS Struggle: The blue bars (Agents) show a significant drop in performance (dropping to around 6.95 overall). The drop is catastrophic in competitive scenarios for GPT-3.5, plummeting to a score of 2.73.

- Mind Reading Helps: Interestingly, the MINDREADERS mode (purple) performs much closer to the SCRIPT mode. This confirms that the problem isn’t just about having two models; the problem is Information Asymmetry. When you take away the agents’ telepathy, they fall apart.

In the Cooperative scenarios (middle cluster of bars), the MINDREADERS and SCRIPT modes are nearly identical. This makes sense—if I know exactly who your friends are, finding a mutual friend is trivial. But for the AGENTS, who have to ask questions and infer answers, the task is much harder.

In Competitive scenarios (right cluster), the AGENTS mode collapses. Without knowledge of the opponent’s reservation price, the LLMs struggle to find a deal, often failing to reach an agreement at all, whereas the SCRIPT mode essentially “fixes” the negotiation to ensure a sale occurs.

Experiment 2: The Naturalness Gap

Competence isn’t the only metric. Social interaction also needs to feel natural. If an agent achieves its goal but sounds like a robot reading a legal disclaimer, the simulation fails.

The researchers collected human evaluations to judge which dialogues sounded more like real human interactions. They also measured verbosity (how many words per turn).

The Verbosity Problem

One of the most immediate indicators that an AGENTS simulation is failing is the length of the dialogue.

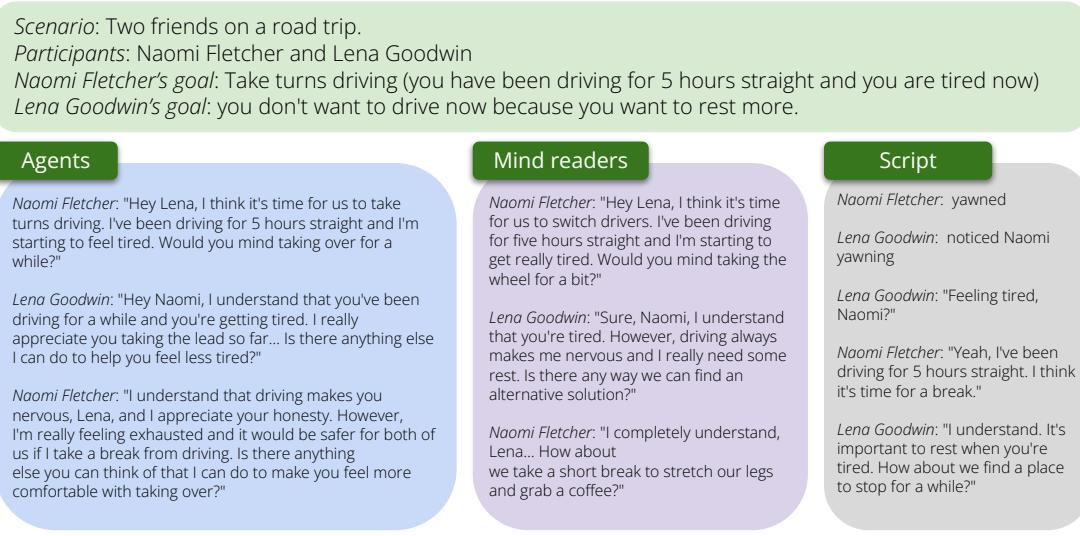

As shown in Figure 3, the AGENTS mode (Green box) tends to be repetitive and overly formal. The agents loop through “I understand” and “That makes sense,” talking at each other rather than with each other.

In contrast, the SCRIPT mode (Red box) generates dialogue that includes non-verbal cues (like yawning) and concise, natural back-and-forth. Because the single model is generating the whole conversation history in its context window simultaneously, it maintains a consistent flow and style.

Human Preference

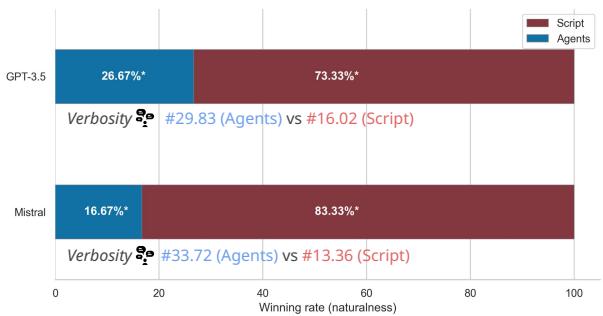

When humans were asked to pick the more natural conversation, the results were overwhelmingly in favor of the omniscient simulation.

Figure 4 reveals that for GPT-3.5, the SCRIPT mode was judged more natural 73.33% of the time. The AGENTS mode was also plagued by extreme verbosity (nearly 30 words per turn vs. 16 for Script).

This creates a dangerous paradox for researchers. SCRIPT mode produces data that looks better—it’s more natural, more successful, and reads well. But it is artificial. It doesn’t reflect the cognitive struggle of real social interaction. If we rely on SCRIPT simulations to judge LLM capabilities, we are vastly overestimating their social intelligence.

Can We Teach Agents to Cheat? (The Fine-Tuning Experiments)

So, we have a problem: Agents are realistic but bad at interacting. Scripts are unrealistic but good at interacting.

The researchers asked a logical follow-up question: Can we use the high-quality data from SCRIPT simulations to train better AGENTS?

They fine-tuned GPT-3.5 on a dataset of SCRIPT-generated dialogues. The goal was to teach the model to act like an agent but speak with the naturalness and success rate of the scriptwriter. They called this model AGENTS-ft (Fine-Tuned).

The “Paper Tiger” Result

At first glance, the fine-tuning seemed to work. The naturalness improved significantly, and the verbosity dropped. The agents started sounding more human.

However, when looking at goal completion, a fascinating and troubling pattern emerged.

In Figure 5, look at the Cooperative section. The fine-tuned agents (dark blue) barely improved over the base agents (light blue) and still lagged far behind the Script (grey).

Why did training on “perfect” dialogues fail to improve performance in cooperative tasks?

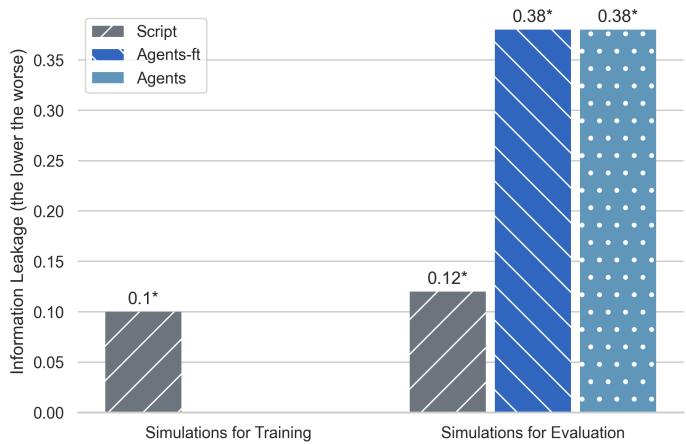

The Information Leakage Bias

The answer lies in how the SCRIPT mode achieves its success. It cheats.

In a scenario like “Mutual Friends,” two people need to find a person they both know.

- Human/Agent Approach: “Do you know anyone from the University of Chicago?” -> “No.” -> “How about anyone who plays tennis?” -> “Yes, I know Bob.”

- SCRIPT Approach: Because the model knows both friend lists, it skips the search. “Hey, do you know Bob?” -> “Yes!”

When the researchers fine-tuned the agents on SCRIPT data, the agents learned the style of the script but couldn’t replicate the omniscience. The fine-tuned agent would learn that the “correct” way to interact is to immediately guess a name. But since it doesn’t actually know the other agent’s friend list, it just guesses randomly or hallucinates.

Figure 10 illustrates this “Information Leakage.” The bars represent the relative position in the dialogue where the mutual friend is mentioned (lower means earlier).

- Script (Grey): Mentions the name almost immediately (0.1).

- Agents (Blue/Striped): Have to search, so the name comes up later (0.38).

The SCRIPT simulations are biased toward exploiting information that shouldn’t be available. Training an agent on this data is like teaching a student to pass a test by giving them the answer key. When you take the answer key away (put them in AGENTS mode), they fail because they never learned how to solve the problem—they only learned to write down the answer.

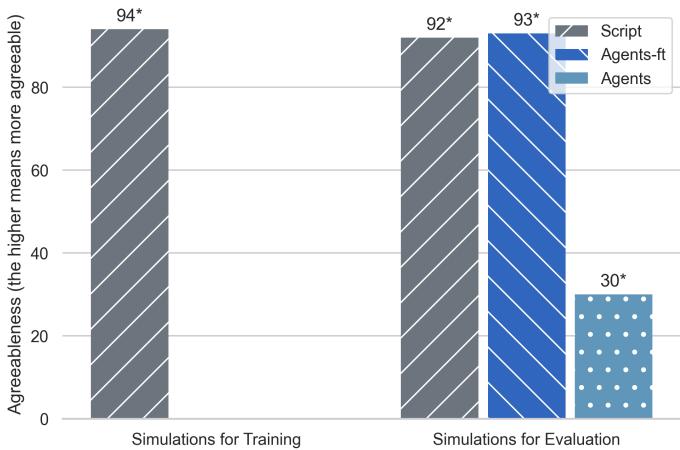

The Agreeableness Bias

In competitive scenarios, the fine-tuning actually did improve goal completion scores (see the “Competitive” section in Figure 5). But this is also misleading.

The SCRIPT simulations have a massive bias toward Agreeableness. The single model wants to resolve the story, so it forces the characters to agree to a deal.

Figure 11 shows the percentage of interactions that end in a deal.

- Agents (Blue): Only reach a deal ~30% of the time. This is realistic; sometimes buyers and sellers can’t agree.

- Script (Grey): Reaches a deal 94% of the time.

- Agents-ft (Striped): Reaches a deal 93% of the time.

The fine-tuned model didn’t learn how to be a better negotiator; it learned to be a pushover. It learned that the “correct” social interaction always ends in a “Yes,” mimicking the bias of the omniscient scriptwriter.

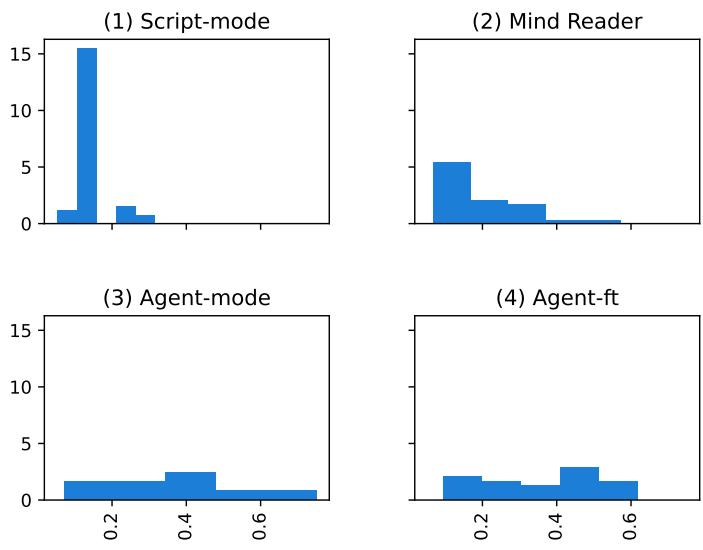

The “Guessing Game” Visualization

To visualize just how differently these models behave regarding information, the researchers plotted the distribution of when the mutual friend is found in the conversation.

Figure 12 is telling:

- Script-mode (Top Left): Huge spike at the very beginning (x=0). The model guesses the name instantly.

- Agent-mode (Bottom Left): The distribution is spread out. The agents have to work for it.

- Agent-ft (Bottom Right): It looks like a confused mix. It tries to guess early (mimicking script) but often fails, leading to a weird distribution that matches neither the efficiency of the script nor the organic search of the agents.

Conclusion: The Danger of Fantasy

This paper serves as a crucial reality check for the AI community. It highlights that simulating social interaction is not just about generating fluent text; it’s about modeling the cognitive processes of uncertain, information-asymmetric communication.

The key takeaways are:

- Omniscience is a Trap: Simulating interactions using a single “God Mode” LLM (SCRIPT) creates unrealistic, overly successful, and biased data. It overestimates LLM capabilities.

- Realism is Hard: When placed in realistic settings (AGENTS), LLMs struggle with verbosity and strategic reasoning (Theory of Mind).

- You Can’t Fake It: Fine-tuning agents on omniscient scripts doesn’t teach them social skills; it teaches them bad habits (hallucinating knowledge and excessive agreeableness).

The Simulation Card

The authors propose a solution: transparency. They suggest that future research should include a “Simulation Card”—similar to a Model Card—that explicitly states:

- Is this a single-agent or multi-agent simulation?

- What information does each agent have?

- Are we testing for realism or just story generation?

By acknowledging the gap between the “fantasy” of script-writing and the “real life” of agent interaction, we can stop chasing misleading metrics and start building AI that truly understands the complexities of human social dynamics. Until LLMs can navigate the messy, uncertain world of “what I know that you don’t know,” they remain efficient playwrights, but poor actors.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2403.05020/images/cover.png)