Introduction

Imagine you have a brilliant encyclopedia, but it was printed in 2021. It knows who the President of the United States is then, but it has no idea about current events, new scientific discoveries, or corrections to mistakes printed in its pages. This is the exact predicament we face with Large Language Models (LLMs). They are static snapshots of the internet at a specific point in time.

When an LLM “hallucinates” or relies on outdated information, our primary instinct might be to retrain it. But retraining a massive model like GPT-J or Llama-2 is astronomically expensive in terms of time and computation. This has given rise to the field of Model Editing—surgical interventions to update specific facts in a model without breaking its general capabilities.

However, existing editing methods face a harsh reality check. Most work well for a single batch of edits (e.g., fixing 100 facts at once) but crumble when you try to edit them consecutively (e.g., fixing 10 facts today, 50 tomorrow, and 200 next week). They either suffer from “catastrophic forgetting” (learning new things makes them forget old ones), require massive external memory banks that grow indefinitely, or require training complex “meta-networks.”

Enter CoachHooK.

In the paper “Consecutive Batch Model Editing with HooK Layers,” researchers propose a novel approach that allows for Consecutive Batch Editing. It is memory-friendly, doesn’t require retraining, and protects the model’s original knowledge while seamlessly integrating new facts. In this post, we will deconstruct how CoachHooK works, the mathematics behind its update mechanism, and why “Hook Layers” are the secret weapon for sustainable LLM maintenance.

Background: The Editing Landscape

To appreciate CoachHooK, we must first understand the problem constraints. Model editing isn’t just about changing a prediction; it is about changing a prediction reliably, ensuring the change generalizes (rephrasing the prompt still works), and ensuring locality (unrelated facts aren’t damaged).

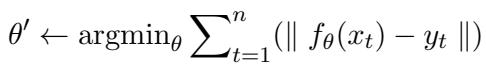

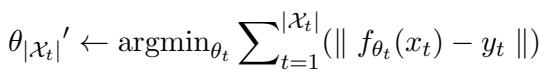

We can categorize the editing scenarios into three levels of difficulty:

1. Single Instance & Batch Editing Standard batch editing tries to minimize the error for a specific set of inputs \(\mathcal{X}_t\) and targets \(y_t\). The goal is to find new parameters \(\theta'\) that satisfy the new facts.

2. Sequential Editing This is harder. Here, edits happen one by one. The model must update itself for fact A, then fact B, then fact C, accumulating changes over time.

3. Consecutive Batch Editing (The CoachHooK Goal) This is the most practical and difficult scenario. We want to update the model in batches effectively, over multiple consecutive steps. We might have a batch of 10 edits today (Step 1), and a batch of 50 edits tomorrow (Step 2). The model needs to integrate the new batch without forgetting the previous batches or the original pre-training data.

Most existing methods fail here. Methods that directly modify weights often degrade quickly over time. Methods that use external memory (like a database of corrections) become slower and heavier as you add more edits. CoachHooK aims to solve this by keeping the original weights frozen and using a lightweight, constant-size “Hook Layer” to handle the changes.

The CoachHooK Method

CoachHooK operates on the principle that Feed-Forward Networks (FFN) in Transformers act as Key-Value Memories. The input to a layer is a “key,” and the output is a “value.” To edit a fact, we essentially want to associate a specific key (a representation of “The Prime Minister of UK”) with a new value (“Rishi Sunak” instead of “Boris Johnson”).

The method has three main pillars:

- Consecutive Batch Updating Mechanism: The math for calculating weight updates.

- The Hook Layer: The architectural component that stores these updates.

- Local Editing Scope Identification: The logic that decides when to use the hook layer.

1. The Consecutive Batch Updating Mechanism

The researchers build upon the MEMIT (Mass-Editing Memory in a Transformer) approach but extend it for consecutive scenarios.

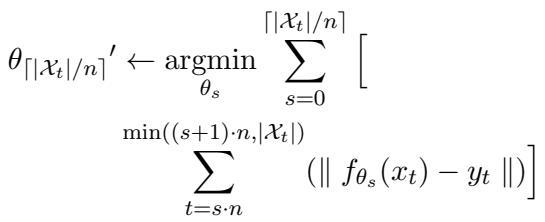

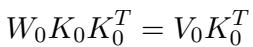

Let’s look at the weights of a layer, \(W_0\). In a pre-trained model, we assume \(W_0\) effectively maps existing keys (\(K_0\)) to existing values (\(V_0\)) using a least-squares objective:

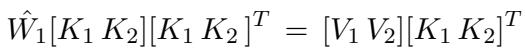

When we want to perform a consecutive edit, we aren’t just solving for the current batch. We are solving for a weight \(\hat{W}_1\) that respects the new batch of keys/values (\(K_2, V_2\)) while preserving the previously edited keys/values (\(K_1, V_1\)).

This looks standard, but here is the twist. We define \(\Delta\) as the change in weights required. By expanding the linear algebra, the researchers derive a formula for \(\Delta\) that considers the residual error (\(R\)) and the accumulated covariance of all keys seen so far (\(C_{accu}\)).

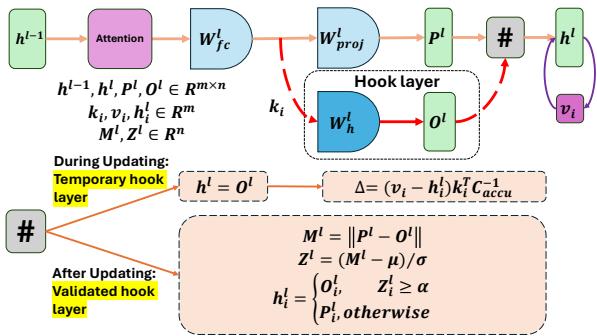

The formula for the weight update \(\Delta\) is:

Here:

- \(R = (V_2 - W_1 K_2)\) is the residual error. It represents the difference between what we want the model to output and what the model currently outputs given the most recent weights.

- \(C_{accu}\) is the accumulation of keys. It ensures that the update is scaled correctly against the “strength” of previous memories.

This mathematical foundation ensures that when we calculate a new update, we are mathematically accounting for the history of edits, minimizing the disruption to previous knowledge.

2. The Hook Layer Architecture

If we kept modifying the original model weights \(W\) repeatedly, the model would eventually “collapse” or drift too far from its original distribution. To prevent this, CoachHooK introduces Hook Layers.

Think of a Hook Layer as a transparent overlay on top of a specific Transformer layer.

- It has its own set of weights, initialized from the original model.

- It acts as a switch. For most inputs, it lets the original model do the work.

- For specific “edited” inputs, it intercepts the data and provides the corrected output.

The architecture involves two states for these hooks:

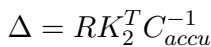

- Temporary Hook Layer: Used during the calculation of the update to compute gradients and residuals based on the most recent state.

- Validated Hook Layer: The “production” state. It stores the finalized weights after an edit step.

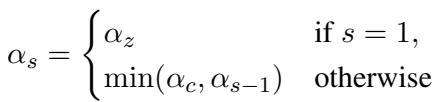

As shown in Figure 1 above, the process is elegant.

- The input \(h^l\) comes in.

- The system computes two outputs: \(P^l\) (from the original frozen weights \(W_{fc}\)) and \(O^l\) (from the hook weights \(W_h\)).

- It calculates the difference (norm) between them.

- Based on this difference, it decides whether to output \(O^l\) (the edited knowledge) or \(P^l\) (the original knowledge).

Crucially, the memory size of the hook layer does not grow. It remains a fixed matrix size (same as the layer it acts upon). You don’t need to store a growing database of examples; the knowledge is compressed into the hook weights \(W_h\).

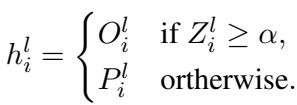

3. Local Editing Scope Identification (The “Switch”)

How does the model know when to use the Hook Layer’s output and when to ignore it? This is the Local Editing Scope Identification.

The researchers discovered a fascinating property: Outlier Detection. If a key \(k_i\) has been updated in the hook weights \(W_h\), the output \(W_h k_i\) will be significantly different from the original output \(W_0 k_i\). If a key \(k_j\) has not been edited, the outputs will likely be very similar.

Therefore, we can detect if an input falls into the “editing scope” by looking at the magnitude of the difference vector \(M^l\):

We can then standardize this magnitude into a Z-score (a statistical measure of how far a data point is from the mean). If the Z-score exceeds a dynamic threshold \(\alpha\), we assume the input relates to an edited fact and swap in the Hook Layer’s output.

This method effectively filters out irrelevant inputs (preserving Locality) while catching the edited inputs (ensuring Reliability).

The threshold \(\alpha\) isn’t fixed; it adapts dynamically. It starts at a preset value and tightens as consecutive edits occur to ensure the scope doesn’t drift too wide.

4. Multi-Layer Scaling

A single layer might not be enough to capture complex edits or might fail to detect the scope correctly. CoachHooK applies this logic across multiple layers iteratively.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the residual error (the correction needed) is distributed across several layers. The system updates Layer 1, recalculates the residuals for the next layers based on that update, then updates Layer 2, and so on. This “layer-increasing iterative manner” ensures a robust update that is harder to “miss” during inference.

Experiments and Results

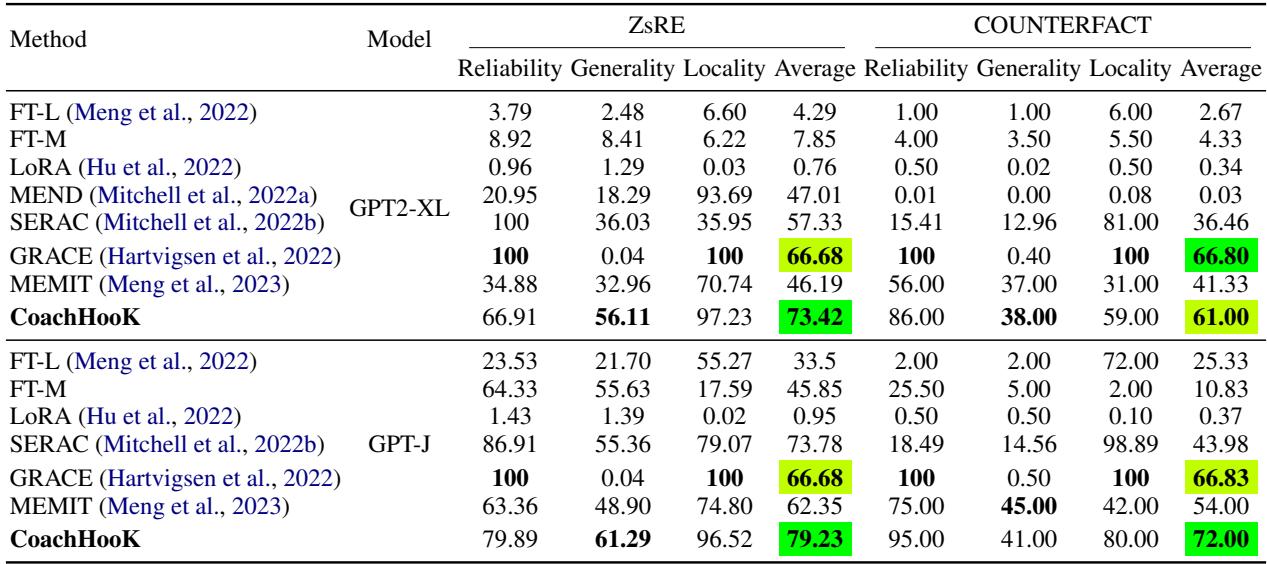

The researchers evaluated CoachHooK against strong baselines like MEMIT, MEND, SERAC, and LoRA using two standard datasets:

- ZsRE: Question-answering dataset.

- COUNTERFACT: A challenging dataset for checking counterfactual updates (e.g., forcing the model to believe the Eiffel Tower is in Rome).

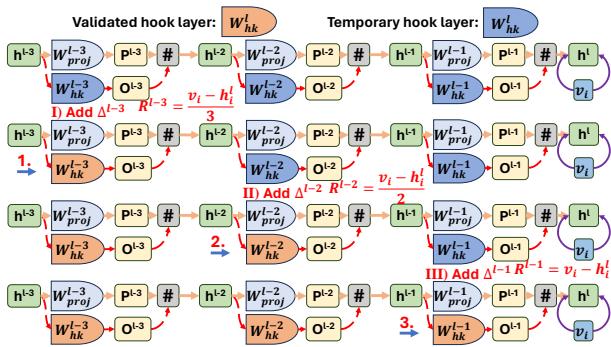

Single-Round Batch Editing

First, they tested a simple single batch (e.g., just one round of edits).

As seen in Table 1, CoachHooK (bottom row) achieves superior results, particularly in Generality (the ability to handle rephrased prompts) on GPT2-XL, while maintaining near-perfect Locality (99.40).

Consecutive Batch Editing

This is the main event. The models were subjected to consecutive streams of edits (1,000 samples in total, broken into batches).

Table 2 reveals the strength of CoachHooK.

- MEMIT (a leading baseline) drops significantly in performance when moved from single-round to consecutive settings (Reliability drops to 34.88 on ZsRE).

- CoachHooK maintains high Reliability (56.11) and massive Generality improvements over methods like GRACE.

- GRACE has high reliability but essentially zero Generality (0.04), meaning it memorizes the specific sentence but fails if you rephrase the question. CoachHooK solves this regurgitation problem.

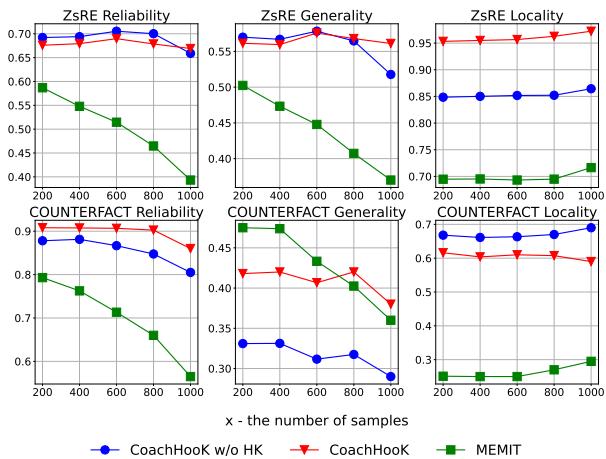

Why does it work? (Ablation Studies)

Is the “Hook Layer” necessary? Or is the math enough?

The researchers ran an ablation study comparing:

- MEMIT (Standard).

- CoachHooK without the Hook Layer (just applying the math to original weights).

- CoachHooK (Full).

Figure 4 (above) shows the results over 1,000 samples.

- Red Triangles (CoachHooK): Consistently perform best.

- Blue Circles (No Hook): Perform better than MEMIT, proving the derived update math is sound.

- Green Squares (MEMIT): Degrade the fastest.

The gap between the Red and Blue lines proves that the Hook Layer architecture specifically helps stabilize the model over long sequences of edits, preventing the “drift” that usually ruins locality.

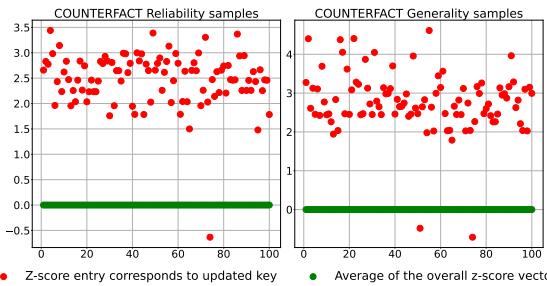

Validating the Scope Detection

One might wonder: Is the Z-score really a good way to detect edited facts?

Figure 3 provides the empirical proof. The red dots (updated keys) consistently show a much higher Z-score than the green line (average/unaffected keys). This clear separation allows the simple thresholding mechanism (\(\alpha\)) to accurately switch between the original model and the hook layer.

Conclusion and Implications

The “CoachHooK” paper presents a significant step forward in the lifecycle management of Large Language Models. By moving away from expensive retraining and static editing methods, it offers a sustainable path for Consecutive Batch Editing.

Key Takeaways:

- Memory Efficiency: Unlike methods that store every edit in a database, CoachHooK compresses updates into fixed-size Hook Layers.

- Stability: The separation of “original weights” and “hook weights” prevents the catastrophic forgetting that plagues standard fine-tuning.

- Scope Intelligence: The use of outlier detection (Z-scores) provides a simple yet statistically grounded way to determine when an edit should be active.

As LLMs become more integrated into daily life, the ability to update them continuously—correcting errors and adding news without full retraining—will be critical. CoachHooK provides a blueprint for how we might keep our AI assistants up-to-date without breaking the bank or the model.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2403.05330/images/cover.png)