Polyglot Pruning: How Parallel Multilingual Input Mimics the Biological Brain

If you have ever tried to learn a second language, you know that your brain often searches for connections. You might anchor a new concept in French by relating it to a concept in English, or perhaps Spanish if you know it. This triangulation helps solidify understanding.

Interestingly, new research suggests that Large Language Models (LLMs) operate somewhat similarly. While models like GPT-4 or Qwen are trained on massive multilingual datasets, we typically interact with them in a “monolingual” tunnel—asking a question in English and expecting an answer in English, or perhaps asking for a translation from German to English.

But what if we treated the model less like a dictionary and more like a multilingual conference?

In a fascinating paper titled “Revealing the Parallel Multilingual Learning within Large Language Models,” researchers demonstrate that feeding an LLM an input in multiple languages simultaneously—a technique they call Parallel Multilingual Input (PMI)—drastically improves performance. But the reason for this improvement is even more surprising: doing so actually “quiets” the neural network, inhibiting redundant neurons and sharpening the model’s focus, much like the biological process of synaptic pruning in the human brain.

In this deep dive, we will unpack how PMI works, the neural mechanism behind it, and why “more languages” might actually equal “less noise.”

1. The Limitation of the Single Lane

Before understanding the solution, we must look at the status quo. The standard way to use an LLM for a task—let’s say, translating a sentence or solving a math problem—is In-Context Learning (ICL). You provide an instruction, maybe a few examples (shots), and the input text.

Even when we get fancy with “Cross-Lingual” prompting (e.g., asking a model to think in English to solve a Chinese problem), we often rely on a pivot strategy. We translate the input to a dominant language (usually English), process it, and translate it back.

The researchers argue that this approach leaves a lot of intelligence on the table. LLMs have learned a “universal representation” of concepts across languages during their massive training. By restricting the input to a single language, we are essentially forcing the model to look at a 3D object through a keyhole.

Enter Parallel Multilingual Input (PMI)

The core contribution of this paper is a new prompting strategy called Parallel Multilingual Input (PMI).

The concept is simple but powerful: instead of giving the model just the source text, you give it the source text plus its translations in several other languages. These translations serve as parallel context anchors.

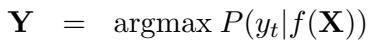

Let’s look at the mathematical difference. In conventional ICL, the model predicts the output \(\mathbf{Y}\) based on a function of the single input \(\mathbf{X}\):

In PMI, the model predicts \(\mathbf{Y}\) based on the input \(\mathbf{X}\) and a set of parallel translations \(\mathbf{M}\):

Here, \(\mathbf{M} = \{m_1, m_2, ..., m_k\}\) represents the same sentence translated into \(k\) different languages.

Visualizing the Difference

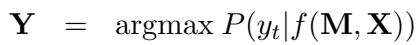

To understand what this looks like in practice, consider the figure below. In the top section (Conventional ICL), the model sees one German sentence. In the bottom section (PMI), the model sees the German sentence, plus Russian, French, Ukrainian, Italian, and Spanish versions.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the prompt provides a rich, multi-perspective context. But look closely at the visualization of the “Network” on the right side of the image. In the Conventional method, many neurons are lit up (red circles). In the PMI method, many neurons are greyed out (inhibited), and the active path is thicker and more distinct.

This visualization hints at the paper’s most significant discovery: PMI changes the neural activation patterns of the model.

2. The Neural Mechanism: Efficiency Through Inhibition

Why does adding more text to the input result in better outputs? One might assume that more data equals more processing and more neuron activation. The researchers found the exact opposite.

To understand this, we need a quick refresher on how neurons in Transformer models (like LLMs) work.

The Life and Death of a Neuron

Inside the Feed-Forward Network (FFN) layers of a Transformer, neurons process information using activation functions. These functions decide whether a neuron should “fire” (pass information forward) or stay silent. Common functions include ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), and its smoother cousins GELU and SiLU.

Crucially, these functions have a gating mechanism. If the input value is negative, they often output zero (or close to it).

Figure 3 above illustrates this concept:

- Panel (a) shows the curves of these functions. Notice how they flatline or dip near zero when the input is negative.

- Panel (c) shows that when an activation function outputs zero, that neuron is effectively “inhibited” or removed from the calculation for that specific token.

The “Quiet” Classroom

The researchers measured the proportion of activated neurons when using standard prompts versus PMI prompts. They discovered a consistent correlation: as you add more languages to the input, the percentage of activated neurons drops.

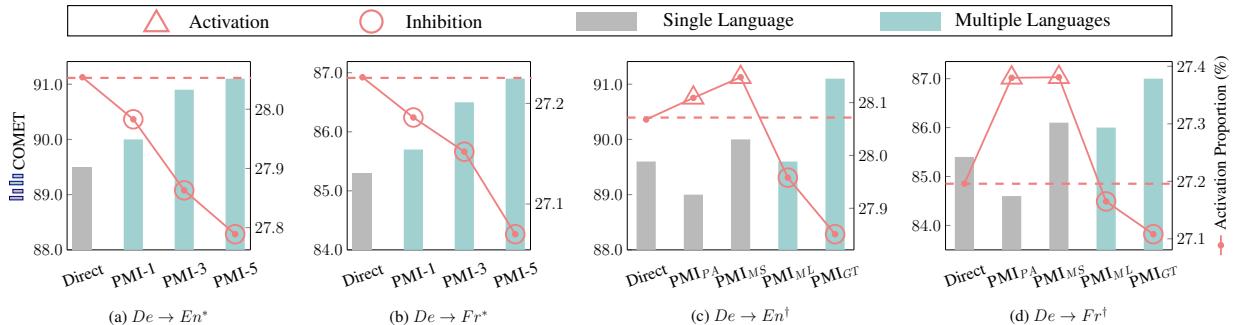

Look at the charts in Figure 4.

- The Red Triangles (Activation) represent performance (COMET score).

- The Blue/Teal Bars represent the Activation Proportion.

In plots (a) and (b), as the number of parallel languages increases (moving right on the x-axis), the performance goes up (red line rises), but the number of active neurons goes down (teal bars shrink).

This suggests that monolingual input is “noisy.” It activates a broad swath of neurons, perhaps because the model is searching for the right context or disambiguating meaning. Multilingual input, by providing triangulation points, allows the model to inhibit irrelevant neurons and focus purely on the core semantic meaning.

Mimicking Synaptic Pruning

The authors draw a compelling parallel to neuroscience. In the human brain, a process called synaptic pruning occurs as we mature. The brain eliminates weaker or unnecessary synaptic connections, making the remaining neural pathways more efficient and powerful. A child’s brain has many more connections than an adult’s, but the adult’s brain is more efficient at processing complex tasks.

PMI seems to induce a “one-off synaptic pruning” during inference. It doesn’t permanently change the model (training does that), but for the duration of that task, it forces the model into a more mature, efficient state.

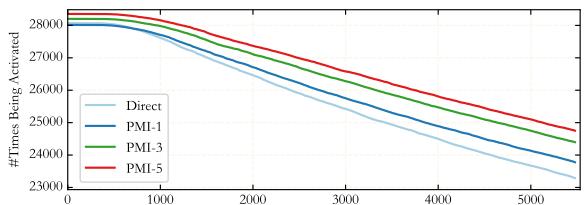

Figure 5 visualizes this “sharpening” effect. The curves show the activation frequency of the top 1% of neurons. The PMI curves (the colored lines) start higher on the left and drop off faster than the Direct prompt. This means the most important neurons are being used more intensely, while the less important ones are being ignored.

3. Dissecting the Source of Improvement

A skeptic might ask: “Is it really the languages helping? Or is it just that we are giving the model more information?”

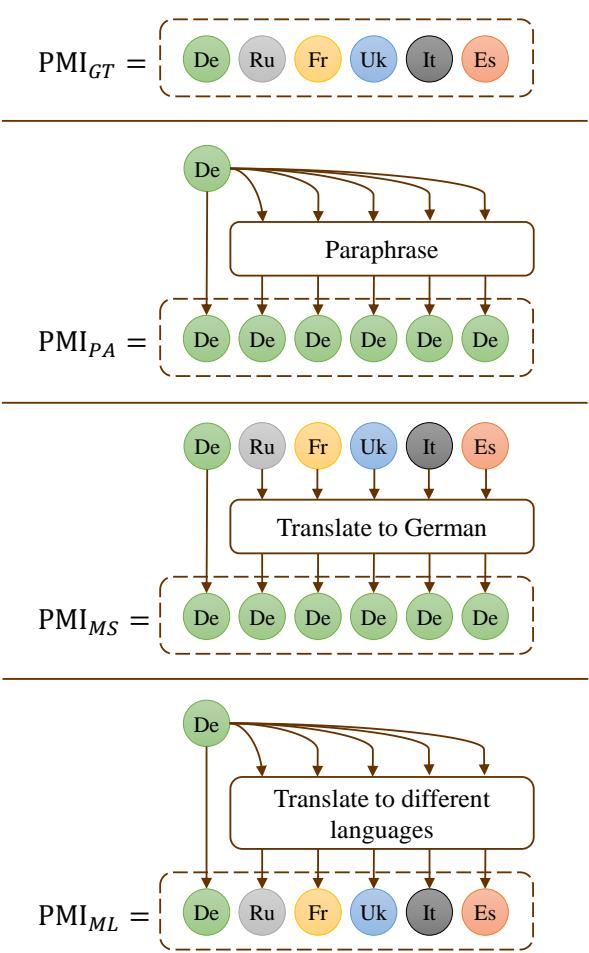

To answer this, the researchers conducted an ablation study using different prompting strategies, visualized below:

They compared four methods (shown in Figure 8):

- PMI_GT: Ground Truth translations (human experts).

- PMI_PA: Paraphrasing the source sentence (Monolingual, Mono-source).

- PMI_MS: Translations back into the source language from different experts (Multi-source, Monolingual).

- PMI_ML: Machine translations into different languages (Mono-source, Multilingual).

The Result: Multilingual prompts (\(PMI_{ML}\)) consistently outperformed monolingual paraphrasing (\(PMI_{PA}\)). Even when the information source was the same (just the original sentence translated by a machine), presenting it in multiple languages unlocked better performance than rephrasing it in the same language.

This confirms that the diversity of linguistic perspective—the “multilingualism” itself—is the key factor triggering the model’s efficient representation.

4. Performance: Does It Actually Work?

The theory is sound, but what about the results? The researchers tested PMI across a variety of tasks, predominantly Machine Translation, but also Natural Language Inference (NLI) and Math Reasoning.

Translation Quality

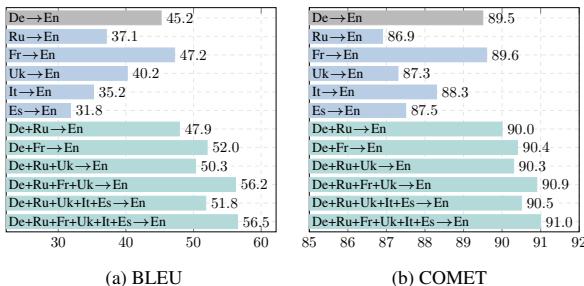

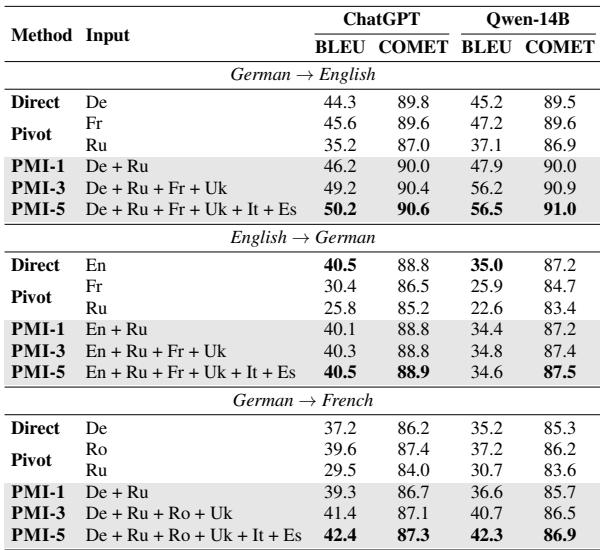

On the FLORES-200 benchmark, the results were striking.

Figure 1 displays the BLEU and COMET scores (metrics for translation quality). The bars on the far right of each chart—representing the combination of 5 or 6 languages—tower over the single-language bars.

- BLEU Score: Improved by up to 11.3 points.

- COMET Score: Improved by 1.52 points (a significant margin in this metric).

Crucially, Table 1 below shows that PMI (especially PMI-3 and PMI-5, meaning 3 or 5 parallel languages) consistently beats both Direct translation and Pivot translation (translating via English).

Beyond Translation: Math and Reasoning

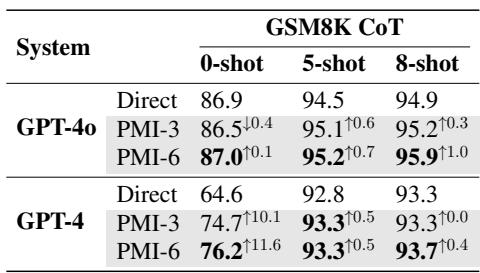

The benefits of PMI aren’t limited to language tasks. The researchers applied this technique to the GSM8K dataset (Math Word Problems). They used GPT-4 to translate the math problems into other languages and then fed them back into the model as parallel input.

As shown in Table 6, using PMI boosted the accuracy of GPT-4 from 64.6% (Direct 0-shot) to 76.2% (PMI-6 0-shot). This is a massive leap, suggesting that seeing a math problem stated in English, French, German, etc., helps the model “understand” the mathematical logic better than English alone.

5. Practical Implementation & Limitations

If you are a student or developer looking to use this, you might be wondering: “Do I need human translations for my prompt?”

The answer is no. The researchers found that you can use the LLM itself (or another machine translation system) to generate the parallel inputs on the fly.

The Workflow:

- Take your input query (e.g., in English).

- Ask the LLM to translate it into French, German, and Spanish.

- Construct a new prompt containing the English original + the 3 generated translations.

- Ask the LLM to perform the final task (reasoning, answering, translating) based on this combined input.

Trade-offs

While effective, PMI does have costs:

- Inference Cost: You are feeding more tokens into the model (the translations), which increases the computational cost and time.

- Latency: Generating the intermediate translations takes time.

However, the authors note that the performance gain often outweighs the cost, especially for complex tasks where accuracy is paramount.

Conclusion: The Universal Language of Thought

The paper “Revealing the Parallel Multilingual Learning within Large Language Models” offers a profound insight into the nature of artificial intelligence. It suggests that LLMs possess a latent, language-agnostic “thought” process.

When we speak to models in one language, we activate a noisy mixture of language-specific and concept-specific neurons. When we speak to them in a chorus of languages, the language-specific noise cancels out, leaving behind a pure, efficient, and highly accurate representation of the underlying concept.

By simulating a form of “synaptic pruning” via prompt engineering, PMI allows us to tap into the full, universal potential of these models. For students and researchers, this opens a new frontier in Prompt Engineering: thinking not just about what we say to the model, but in how many ways we say it.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2403.09073/images/cover.png)