Knowledge Graphs (KGs) are the unsung heroes of modern AI. They power the decision-making behind recommendation engines, enhance the accuracy of question-answering systems, and provide the structured “world knowledge” that unstructured text lacks.

But building a Knowledge Graph is notoriously difficult. Traditionally, it required intensive human labor to define schemas (the rules of the graph) and map data to them. Recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 have shown promise in automating this process. You simply give the LLM a piece of text and a list of allowed relations (the schema), and ask it to extract the data.

There is a catch. Real-world schemas are huge. Wikidata, for example, has thousands of relation types. You cannot fit a massive schema into the context window of an LLM prompt. Even if you could, the model would likely get “lost in the middle,” ignoring instructions buried in a wall of text.

So, how do we scale automated Knowledge Graph Construction (KGC) without hitting these limits?

In this post, we will dive into a recent paper titled “Extract, Define, Canonicalize: An LLM-based Framework for Knowledge Graph Construction” by Bowen Zhang and Harold Soh. They propose a clever three-phase framework called EDC that separates the extraction of information from the mapping of schema, allowing for high-quality graph construction even with massive or non-existent schemas.

The Core Problem: The Schema Bottleneck

To understand the innovation here, we first need to look at the standard approach, often called Closed Information Extraction.

In Closed IE, you have a pre-defined set of relations, such as bornIn, worksFor, or invented. You provide a sentence to an LLM along with this list and say: “Extract triplets that fit these specific relations.”

This works well for small, domain-specific tasks. But in the wild, this approach crumbles:

- Context Window Overflow: Large schemas exceed the token limit.

- Rigidity: If the text describes a relationship that isn’t in your pre-defined list, the information is lost.

- Unknown Schemas: Sometimes, you don’t even know what you are looking for yet—you want the data to tell you what the schema should be.

The researchers propose a shift in perspective: Don’t force the schema during extraction. Fix it afterwards.

The EDC Framework

The researchers introduce EDC, which stands for Extract, Define, and Canonicalize. Instead of trying to do everything in one prompt, they break the task down into three distinct phases that play to the LLM’s strengths.

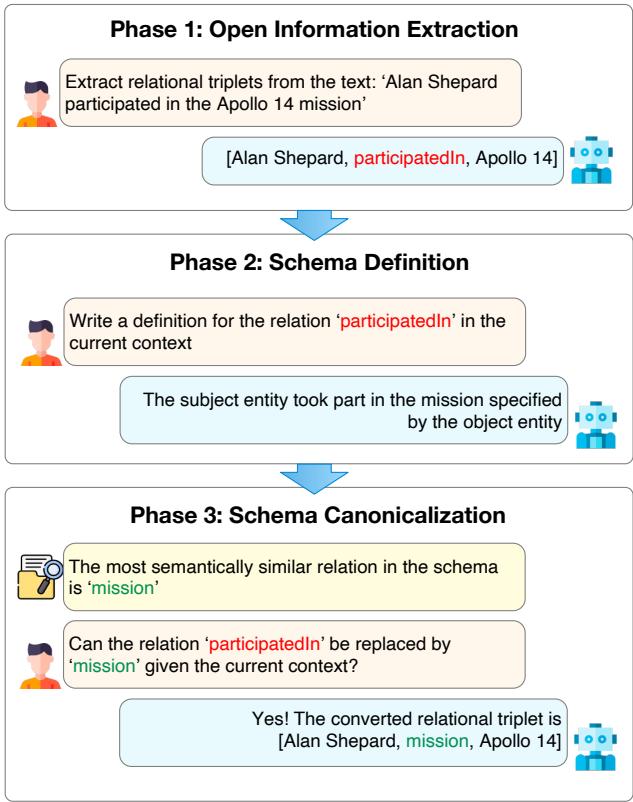

As shown in Figure 1 above, the process transforms raw text into a structured, standardized triplet. Let’s walk through the example used in the paper: “Alan Shepard participated in the Apollo 14 mission.”

Phase 1: Open Information Extraction (Extract)

In this phase, the goal is simple: get the information out. We do not burden the LLM with a complex schema list. We use Open Information Extraction (OIE).

We prompt the LLM to identify entities and their relationships freely.

- Input: “Alan Shepard participated in the Apollo 14 mission.”

- Output:

[Alan Shepard, participatedIn, Apollo 14]

The LLM is free to use whatever words appear in the text or make sense naturally. While this captures the semantic meaning, it’s messy. One text might say “participatedIn,” another might say “took part in,” and a third might say “was a crew member of.” To a computer, these are three different relations, which creates a redundant and messy graph.

Phase 2: Schema Definition (Define)

This is the most creative step in the framework. To fix the messiness of OIE, we first need to understand exactly what the LLM meant when it extracted those triplets.

Ambiguity is the enemy of structure. The word “run” means something very different in “run a company” versus “run a marathon.”

The EDC framework asks the LLM to write a definition for the relation it just extracted, based on the specific context of the sentence.

- Prompt: Write a definition for the relation ‘participatedIn’ in the current context.

- LLM Output: “The subject entity took part in the mission specified by the object entity.”

Now, we have more than just a label; we have a semantic understanding of the relationship.

Phase 3: Schema Canonicalization (Canonicalize)

Now we need to standardize (canonicalize) the triplet. We want to map the free-text relation participatedIn to a standardized relation from our target schema (if we have one).

The system uses Vector Similarity Search. It takes the definition generated in Phase 2 and compares it against the definitions of relations in the target schema.

- Embedding: The definition “The subject entity took part in the mission…” is converted into a vector embedding.

- Search: It searches the target schema for the most semantically similar relation. Let’s say the target schema contains a relation called

mission. - Verification: To prevent errors (over-generalization), the LLM is shown the candidate (

mission) and asked: “Can ‘participatedIn’ be replaced by ‘mission’ given the context?” - Result: If the LLM says yes, the triplet is converted.

- Final Output:

[Alan Shepard, mission, Apollo 14]

This approach allows the system to handle schemas with thousands of relations because you never need to put the full schema in the prompt. You only retrieve the most relevant candidates for verification.

Two Modes of Operation

One of the strengths of EDC is its flexibility. It works in two distinct settings:

- Target Alignment: This is what we described above. You have a massive existing schema (like Wikidata), and you want your extracted data to conform to it.

- Self-Canonicalization: You have no schema at all. You want to build a Knowledge Graph from scratch. In this mode, EDC starts with an empty schema. As it processes text, it builds a schema dynamically. If a new relation looks similar to one already in the list (based on the definition), it merges them. If it’s new, it adds it. This results in a concise, self-generated schema without human intervention.

Enhancing Performance: EDC+R (Refinement)

The three-phase process is effective, but sometimes the initial extraction (Phase 1) misses subtle details because it’s operating “blind” without knowledge of the valid relations.

To address this, the authors introduce a refinement step, creating EDC+R.

The idea is borrowed from Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). After the first pass of extraction, the system pauses. It uses a trained Schema Retriever to scan the target schema and find relations that might be relevant to the input text, even if the LLM didn’t catch them the first time.

The Schema Retriever

The Schema Retriever is a crucial component. It isn’t just a standard keyword search. It is a fine-tuned embedding model (based on E5-mistral-7b) trained to understand the relevance between a raw sentence and a relation type.

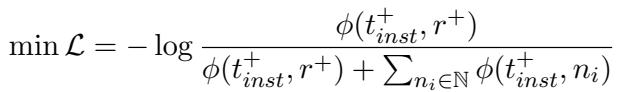

The training uses a contrastive loss function (InfoNCE). If that sounds complex, don’t worry. The logic is captured in the equation below:

What this equation tells us: We want to maximize the similarity score (\(\phi\)) between the input text (\(t_{inst}^+\)) and the correct relation (\(r^+\)), while minimizing the similarity with all other negative (incorrect) relations (\(n_i\)).

By training the model this way, the retriever learns to look at a sentence like “She leads the engineering department” and predict that the relation headOfDepartment is highly relevant, even if the word “head” never appears in the text.

The Feedback Loop

In the refinement phase, the system runs the extraction again, but this time it provides a “Hint” in the prompt: “Here are some potential relations and their definitions you may look out for: [List retrieved by Schema Retriever].”

This “bootstrapping” allows the LLM to catch relations it missed initially, significantly improving recall.

Experiments and Results

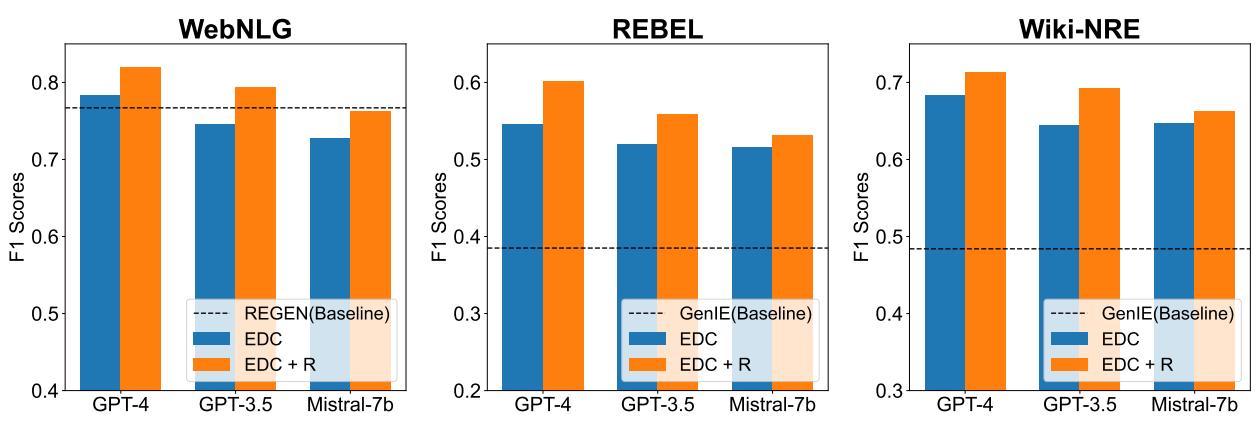

Does this actually work? The researchers tested EDC on three major Knowledge Graph benchmarks: WebNLG, REBEL, and Wiki-NRE. These datasets vary in size and complexity, offering a rigorous test ground.

They compared their framework against state-of-the-art baselines like REGEN and GenIE.

Target Alignment Results

The main results are summarized in the figure below. The metrics used are F1 scores (a balance of precision and recall).

Key Takeaways from the Data:

- EDC beats the Baselines: On almost every metric, the EDC framework (blue bars) outperforms the specialized, fully trained baseline models (dashed lines).

- Refinement is Powerful: The orange bars (EDC+R) are consistently higher than the blue bars. Adding the Schema Retriever and the refinement loop provides a significant boost.

- Model Agnostic: The framework works well across different LLMs, including GPT-4, GPT-3.5, and the open-source Mistral-7b, though stronger models like GPT-4 obviously perform best.

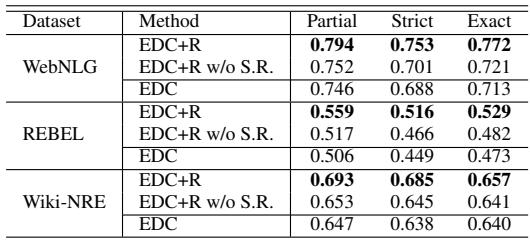

Does the Retriever Really Matter?

You might wonder if the improvement in EDC+R comes just from asking the model to try again, or if the retrieved hints are actually helping. The researchers performed an ablation study to find out.

Table 1 confirms the value of the retriever. When the researchers ran EDC+R but removed the retrieved schema hints (the row “EDC+R w/o S.R.”), the performance dropped significantly across all datasets. This proves that the semantic hints provided by the trained retriever are essential for guiding the LLM to the correct relations.

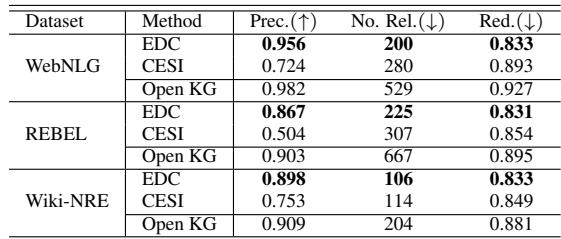

Self-Canonicalization Performance

What about the scenario where we don’t have a target schema? The researchers evaluated how well EDC could build a graph from scratch. They measured:

- Precision: Are the extracted triplets correct?

- Conciseness: Did the model create too many duplicate relations? (Lower number of relations is generally better).

- Redundancy: Are the relations distinct from each other?

They compared EDC against CESI, a standard clustering-based method for canonicalizing open knowledge graphs.

As shown in Table 2, EDC dominates. It achieves much higher precision while generating a schema that is significantly more concise (fewer relations). For example, on the WebNLG dataset, the raw Open KG had 529 relations. CESI reduced this to 280, but EDC managed to condense it to 200 high-quality relations with lower redundancy.

This suggests that EDC understands the semantics of relations much better than traditional clustering methods, avoiding the trap of grouping unrelated concepts together (over-generalization) or failing to merge similar ones (under-generalization).

Conclusion and Future Implications

The Extract-Define-Canonicalize framework represents a significant step forward for automated Knowledge Graph construction. By decoupling extraction from schema validation, it solves the context window bottleneck that has plagued LLM-based approaches.

Why this matters for students and practitioners:

- Scalability: You can now apply LLMs to datasets with massive schemas (like medical or legal ontologies) without fine-tuning specialized models.

- Flexibility: The ability to switch between Target Alignment and Self-Canonicalization means one tool can handle both strict database entry and open-ended exploratory data analysis.

- Interpretability: Because the system generates natural language definitions for every relation it extracts (Phase 2), the resulting graph is more transparent. You can inspect why an LLM classified a relationship the way it did.

As we move toward systems that need to process vast amounts of unstructured text—from constructing memories for robots to organizing scientific literature—frameworks like EDC will be essential tools in bridging the gap between the fluidity of language and the rigidity of structured data.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2404.03868/images/cover.png)