If you have used ChatGPT, Gemini, or any modern Large Language Model (LLM) for any significant amount of time, you have likely encountered it: the moment the machine confidently asserts something that is factually untrue. It might invent a court case that never happened, attribute a quote to the wrong historical figure, or generate a URL that leads nowhere.

We call this “hallucination.” It is widely considered the Achilles’ heel of modern Artificial Intelligence.

However, a recent comprehensive study by researchers from Pennsylvania State University, Adobe Research, and Georgia Institute of Technology suggests that our biggest problem might not just be the hallucinations themselves, but the fact that the Natural Language Processing (NLP) community cannot agree on what the term actually means.

In their paper, “An Audit on the Perspectives and Challenges of Hallucinations in NLP,” the authors argue that the field is suffering from a lack of consensus. Through a rigorous audit of 103 peer-reviewed papers and a survey of 171 practitioners, they reveal a fragmented landscape where definitions are vague, metrics are inconsistent, and the “sociotechnical” impact—how these errors affect real people—is often overlooked.

In this deep dive, we will unpack their findings, explore the history of the term, and analyze why solving the “hallucination” problem requires us to first fix our vocabulary.

Part 1: The Explosion of the “H-Word”

To understand the current confusion, we have to look at the trajectory of the research. “Hallucination” isn’t a new term in computer science, but its application to text generation has skyrocketed in correlation with the release of consumer-facing LLMs.

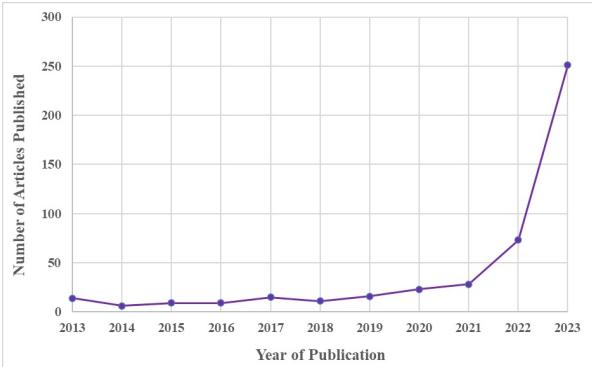

The authors tracked the usage of the term in peer-reviewed literature indexed in SCOPUS. As illustrated below, the interest in this topic was relatively flat for nearly a decade. Then, around 2022 and 2023—coinciding with the rise of GPT-3 and ChatGPT—the research output exploded.

While this graph represents progress, the authors point out a critical flaw: volume does not equal clarity. As thousands of researchers rushed to study this phenomenon, they brought with them differing definitions, methodologies, and measurement tools.

A Brief History of Machine Hallucinations

The paper provides a fascinating etymology of the term in CS:

- Computer Vision (2000s): The term was originally used in image processing. “Hallucinating faces” referred to increasing the resolution of an image by inferring (or “hallucinating”) new pixel values that weren’t present in the original low-res input. In this context, it was a desired feature.

- RNNs (2015): Andrej Karpathy introduced the term to NLP in a blog post about Recurrent Neural Networks. He described how a model could generate nonexistent URLs, effectively “hallucinating” data.

- The LLM Era: Today, it refers almost exclusively to a negative behavior—the generation of unfaithful or non-factual text.

The problem identified by the authors is that while the term stuck, a unified framework for it did not.

Part 2: Auditing the Literature

To diagnose the state of the field, the researchers conducted a systematic audit of 103 peer-reviewed papers from the ACL Anthology. They filtered specifically for works that treated hallucination as a primary focus, rather than just a passing mention.

Where Do Hallucinations Happen?

One of the first questions the audit sought to answer was: In what context are researchers studying hallucinations?

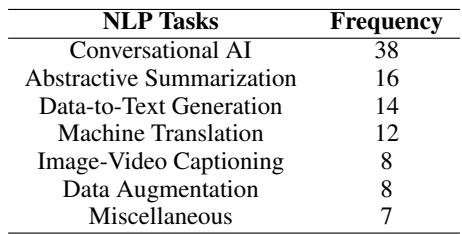

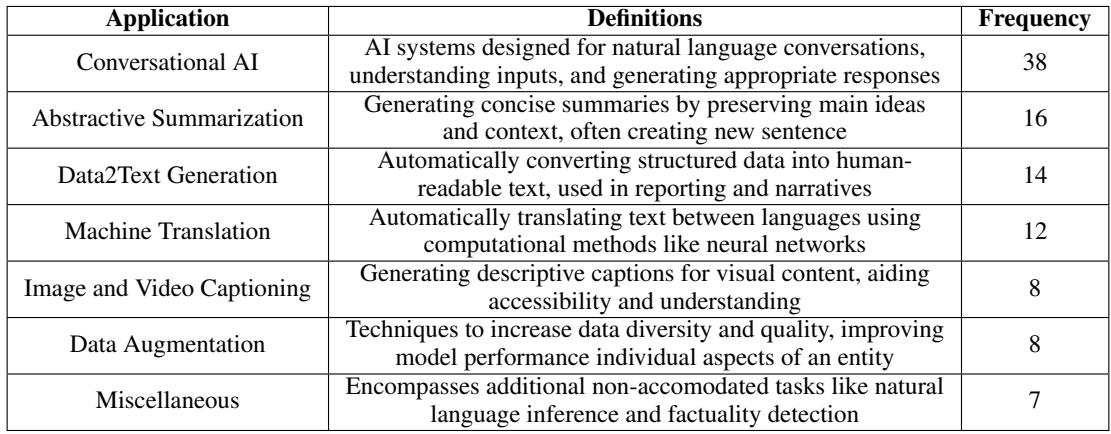

The analysis revealed that hallucination research is not monolithic; it is fractured across different NLP tasks. As shown in the table below, the bulk of the research focuses on Conversational AI (chatbots), followed by Abstractive Summarization and Data-to-Text Generation.

This distinction matters because “hallucination” means something different in each context:

- In Translation, a hallucination might be a sentence that drastically changes the meaning of the source text.

- In Summarization, it might be including a detail that wasn’t in the original article.

- In Dialogue, it might be the chatbot inventing a fact about the world that sounds plausible but is false.

The Definition Deficit

Here lies the paper’s most damning finding: Out of 103 papers regarding hallucination, only 44 (42.7%) actually provided a definition of the term.

The majority of researchers (57.3%) assumed the reader knew what they meant, or simply didn’t define their terms. Among those who did define it, the authors found 31 unique frameworks. This indicates a massive lack of standardization.

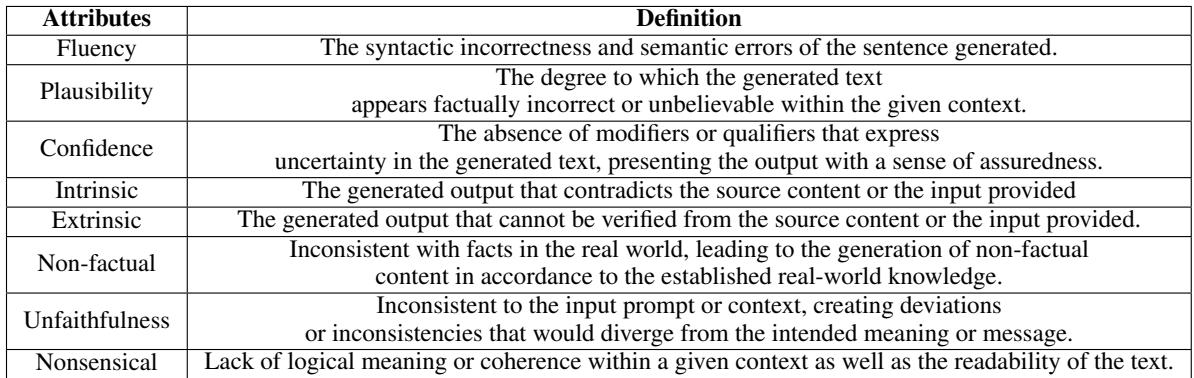

Through thematic analysis, the authors distilled these varied definitions into a set of core attributes:

- Fluency: Is the text grammatically correct?

- Plausibility: Does it sound believable?

- Confidence: Does the model sound sure of itself?

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic: This is a crucial distinction proposed in earlier works.

- Intrinsic: The output contradicts the input (e.g., the article says “it rained,” the summary says “it was sunny”).

- Extrinsic: The output contains information not found in the input (e.g., the article says “it rained,” the summary says “it rained in London,” when London wasn’t mentioned).

The authors compiled these attributes to show how different papers mix and match them to create their own custom definitions.

The Measurement Crisis

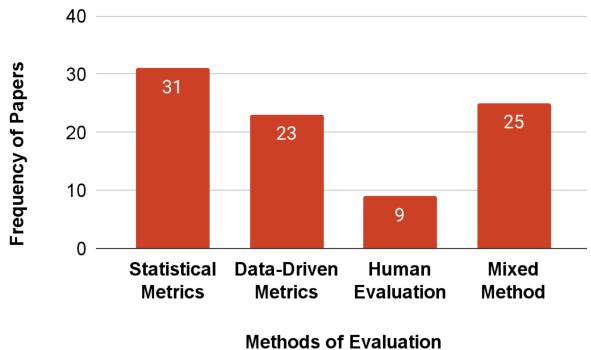

If we can’t agree on a definition, how are we measuring the problem? The audit found that the community is split on metrics, too.

The researchers categorized the evaluation methods into four buckets:

- Statistical Metrics: Using formulas like BLEU or ROUGE to calculate word overlap.

- Data-Driven Metrics: Using other models (like a Natural Language Inference model) to check for contradictions.

- Human Evaluation: Asking people to rate the output.

- Mixed Methods: Combining the above.

The challenge: The authors note that statistical metrics (used in over 35% of works) are often ill-suited for measuring hallucination. A sentence can have high word overlap with the truth (high BLEU score) but still contain a fatal factual error. Conversely, human evaluation is expensive and subjective.

Part 3: The Practitioner’s Perspective

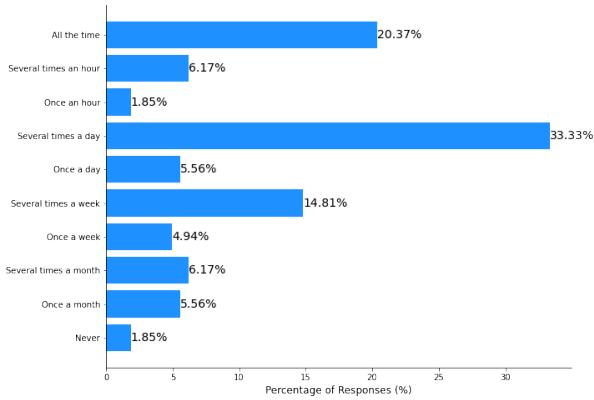

Moving beyond the theoretical, the researchers wanted to understand how “hallucination” is perceived by the people actually building and using these systems. They conducted a survey of 171 practitioners (PhD students, professors, and industry professionals).

Everyone Knows It, Few Understand It

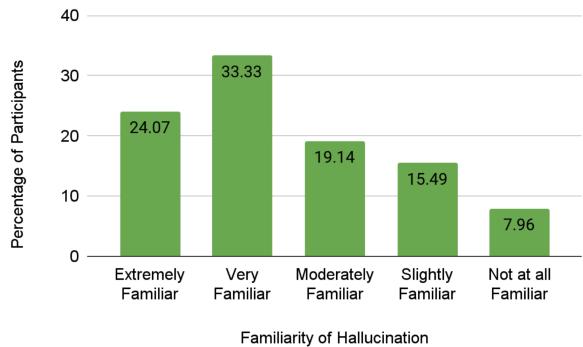

The survey results showed that the community is highly aware of the problem. Over 57% of respondents claimed to be “Very” or “Extremely” familiar with the concept.

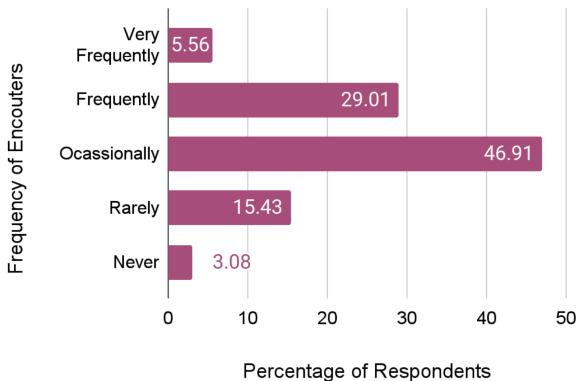

Furthermore, the practitioners reported encountering these errors frequently. As the chart below indicates, nearly 30% encounter hallucinations “Frequently” and nearly 47% “Occasionally.” It is a pervasive part of the AI workflow.

Is “Hallucination” the Wrong Word?

One of the most interesting qualitative findings of the survey was the debate over terminology.

While 92% of respondents viewed hallucination as a weakness of LLMs, there was significant pushback against the word itself. The term “hallucination” implies a psychological process—a mind perceiving something that isn’t there. But LLMs don’t have minds; they have statistical probabilities.

Survey respondents suggested alternative terms:

- Fabrication: implies the construction of false data.

- Confabulation: implies the creation of false memories without the intent to deceive.

- Misinformation: focuses on the outcome rather than the process.

One respondent noted: “Fabrication makes more sense. Hallucination makes it feel like AI is human and has the same sensory perceptions… which could lead to hallucinations.”

The “Creativity” Argument

Surprisingly, 12% of respondents did not view hallucination purely as a negative. In creative writing or image generation, the model’s ability to diverge from reality is a feature, not a bug. If you ask an LLM to write a sci-fi novel, you want it to “hallucinate” a world that doesn’t exist.

This duality—where the same behavior is a critical failure in a medical chatbot but a brilliant feature in a creative writing tool—makes defining a universal framework for “hallucination” even harder.

Part 4: The Impact of Disagreement

Why does all this academic quibbling over definitions matter? The authors argue that the lack of clarity has real-world consequences, particularly as these systems are deployed in sociotechnical environments (healthcare, law, education).

The paper breaks down the different frameworks used across specific sub-fields to highlight the inconsistency.

(Note: While the caption in the image refers to “Sentiment Analysis,” the table content clearly details how hallucination is defined across various NLP tasks like Conversational AI and Machine Translation.)

For example:

- Conversational AI focuses on “Fluency” and “Non-factuality.”

- Machine Translation focuses almost exclusively on “Extrinsic” errors (adding things that weren’t in the source).

- Image Captioning emphasizes “Object Hallucination” (seeing a cat where there is none).

Because these fields don’t talk to each other, a technique invented to fix hallucinations in translation might be completely ignored by researchers working on summarization, simply because they are using different definitions and metrics.

The Trust Gap

The survey also highlighted that this unpredictability erodes trust. Respondents noted that they cannot rely on LLMs for scholarly work or coding without intense supervision.

One respondent shared: “I was asking an AI to generate me a piece of code. It ended up picking some code from one website and some from another… the resulting code couldn’t be executed.”

The ubiquity of these tools means that “hallucination” is no longer just a research problem; it is a user experience crisis.

Conclusion: A Call for Standardization

The research paper concludes with a clear message: We cannot solve what we cannot define.

The authors propose a set of “Author-Centric” and “Community-Centric” recommendations to move the field forward:

- Explicit Documentation: Papers must explicitly define what they mean by “hallucination.” Do not assume the reader knows.

- Standardized Nomenclature: The community needs to decide when to use “hallucination” versus “confabulation” or “fabrication.” These terms should not be interchangeable.

- Sociotechnical Awareness: We must acknowledge that these models operate in a social world. A hallucination in a poem is harmless; a hallucination in a medical diagnosis is dangerous. Our frameworks must account for the context of the error.

- Transparency: Developers need to create methods that allow users to see why a model might be hallucinating, fostering better trust.

The rapid rise of LLMs has outpaced our ability to rigorously categorize their failures. This audit serves as a necessary pause—a moment for the field to stop, look at the chaotic landscape of definitions, and agree on a common language before rushing to the next breakthrough.

Only by standardizing our understanding of “hallucination” can we hope to mitigate it effectively.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2404.07461/images/cover.png)