Introduction: The “Garbage In, Garbage Out” Dilemma

In the world of Machine Learning, there is an old adage that every student learns in their first semester: “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” No matter how sophisticated your neural network architecture is—whether it’s a state-of-the-art Transformer or a massive Large Language Model (LLM)—it cannot learn effectively if the data it is fed is flawed.

For years, the gold standard for solving this problem was human annotation. If a dataset was messy, you hired humans to read it, label it, and clean it. But as datasets have exploded in size, reaching millions of examples, relying on human labor has become prohibitively expensive and slow. This leaves researchers in a bind: do we accept noisy data and lower performance, or do we burn through budgets cleaning it?

A recent paper titled “MULTI-NEWS+: Cost-efficient Dataset Cleansing via LLM-based Data Annotation” proposes a third option. The researchers demonstrate that we can turn the tables on AI, using Large Language Models not just as the output of our training, but as the custodians of our data.

In this deep dive, we will explore how the authors used LLMs to automatically “cleanse” the popular Multi-News dataset. We will break down their novel framework involving Chain-of-Thought prompting and majority voting, and we will see how removing “noise” led to a statistically significant boost in model performance.

The Problem with Web-Scraped Data

To understand the solution, we first need to understand the mess. The paper focuses on Multi-Document Summarization, a task where a model must read several articles about the same topic and write a single, coherent summary.

The standard benchmark for this task is the Multi-News dataset. It was constructed by scraping news articles referenced by newser.com. While this sounds straightforward, automated web crawling is prone to errors. When a bot scrapes a webpage, it doesn’t “understand” the page; it just grabs text.

Often, the scraper grabs content that is technically on the page but irrelevant to the story. This includes:

- Standard website disclaimers (“This copy is for personal use only…”).

- System messages (“Please enable cookies…”).

- Totally unrelated tweets or sidebar links.

- Archival metadata (Wayback Machine banners).

Visualizing the Noise

The authors identified that a significant portion of the Multi-News dataset contains this “noise.” If a summarization model is trained on this, it might learn to hallucinate or include irrelevant details.

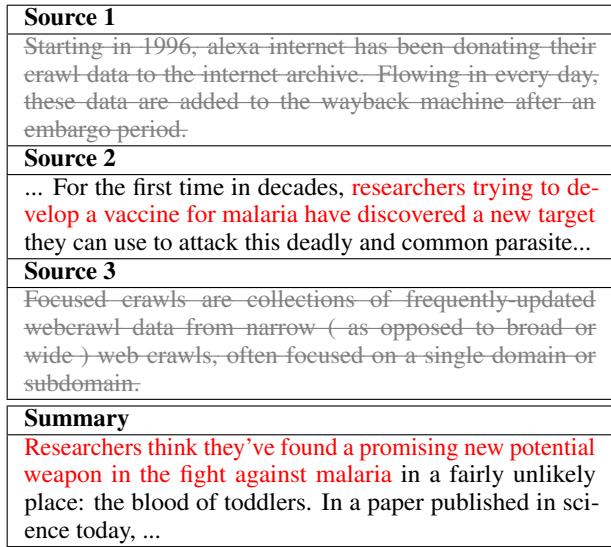

Take a look at the table below. This is a direct example from the paper showing what “noise” looks like in practice.

In Table 1, look at Source 1 and Source 3. Source 1 is a generic description of Alexa Internet’s data donation to the Internet Archive. Source 3 defines what a “focused crawl” is. Neither of these has anything to do with the Summary, which discusses a malaria vaccine. Only Source 2 is actually relevant. Yet, in the original dataset, all three are treated as valid input documents for the model to learn from.

The Source of the Error

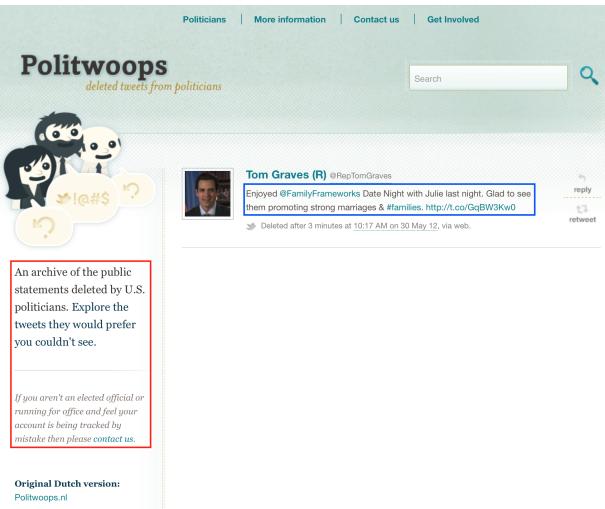

Why does this happen? Sometimes it’s a failure of the scraping logic. The authors highlight a fascinating technical glitch where the scraper targeted the wrong HTML container.

As shown in Figure 3, the scraper intended to grab the politician’s tweet (the blue box). Instead, it grabbed the sidebar text (the red box) which explains what the website “Politwoops” does. Because this sidebar is identical on every page of that website, the dataset ended up with hundreds of documents containing the exact same irrelevant sidebar text instead of the actual news.

The Solution: An LLM-Based Cleansing Framework

The core contribution of this paper is a framework to fix these issues without a human in the loop. The researchers hypothesized that modern LLMs (specifically GPT-3.5-turbo) possess enough semantic understanding to distinguish between a relevant news story and a boilerplate disclaimer.

However, you can’t just ask an LLM “Is this relevant?” and expect perfect results. LLMs can hallucinate, be inconsistent, or misunderstand the nuance of “relevance.” To mitigate this, the authors designed a robust four-step framework combining Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting and Majority Voting.

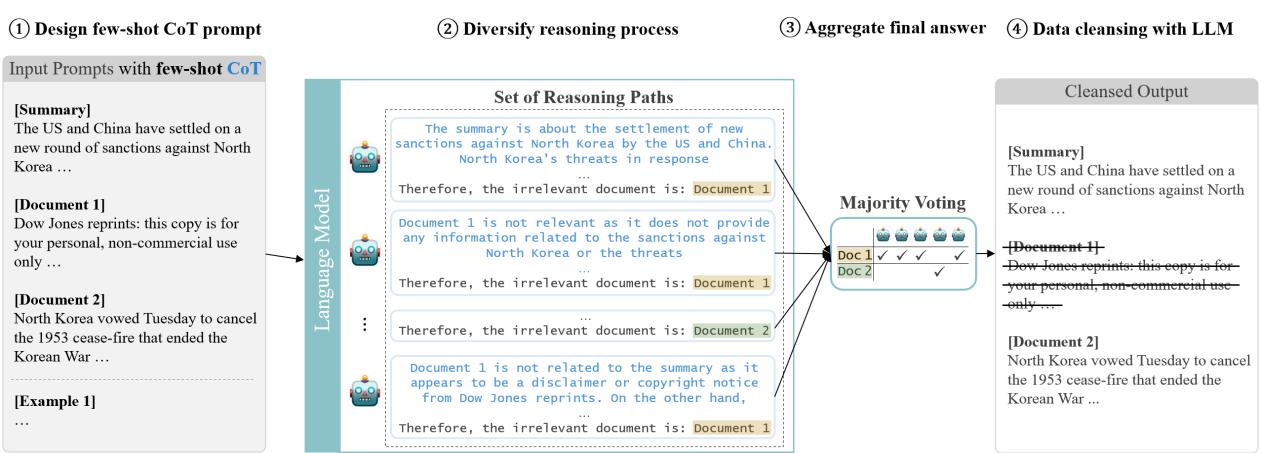

Let’s break down the architecture illustrated in the figure below.

Step 1: Design Few-Shot CoT Prompt

The first step (Figure 1, Step 1) involves prompt engineering. The authors didn’t just provide instructions; they used Few-Shot Learning. They gave the model examples of inputs (documents and summaries) and the desired outputs (classification of relevance).

Crucially, they used Chain-of-Thought (CoT). Instead of asking the model for a simple “Yes/No” label, they asked the model to generate a rationale. The model must explain why a document is irrelevant (e.g., “This document is a copyright disclaimer and contains no facts related to the summary”) before giving the final verdict. This forces the model to reason through the content, significantly improving accuracy.

Step 2: Diversify Reasoning Process

LLMs are probabilistic. If you ask the same model the same question twice, you might get different answers. To turn this bug into a feature, the researchers instantiated five different LLM agents (Step 2 in Figure 1).

Each agent independently reads the summary and the source documents. They each generate their own Chain-of-Thought reasoning. One agent might focus on the lack of shared keywords, while another might focus on the semantic mismatch.

Step 3: Aggregate Final Answer (Majority Voting)

Once the five agents have made their decisions, the system aggregates the results (Step 3). They use a majority voting mechanism (Self-Consistency).

- If Agent 1 says “Relevant”

- If Agent 2 says “Irrelevant”

- If Agents 3, 4, and 5 say “Relevant”

The system concludes the document is Relevant (4 vs 1). This mimics how human annotation works, where multiple annotators review data to ensure consensus, smoothing out individual errors or biases.

Step 4: Data Cleansing

Finally, based on the consensus, the system creates the new dataset, MULTI-NEWS+. Documents deemed irrelevant by the majority are physically removed from the input sets.

The Transformation: Creating MULTI-NEWS+

The researchers applied this framework to the entire Multi-News dataset, which contains over 56,000 sets of summaries and documents.

The cost efficiency here is remarkable. Annotating this volume of data with humans would cost tens of thousands of dollars and take months. Using the GPT-3.5 API, the total cost was approximately $550.

What was removed?

The cleansing process was aggressive. The model identified that a substantial portion of the original dataset was noise.

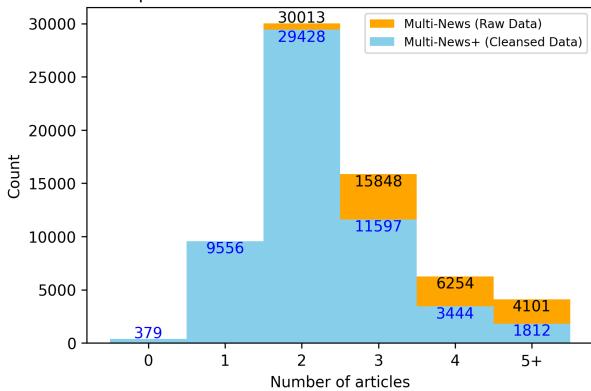

Figure 2 shows the distribution of articles per summary.

- The Orange bars represent the original raw data.

- The Blue bars represent the cleansed MULTI-NEWS+ data.

Notice the shift to the left. The blue bars are higher for lower numbers (2, 3, 4 articles) and lower for high numbers (5+ articles). This indicates that many “5-article” sets were actually “2 valid articles + 3 junk files.”

Perhaps the most shocking statistic is that 379 sets were found to have zero relevant source articles. In these cases, the summary was written based on information that simply wasn’t present in the provided source documents (likely due to the scraping errors mentioned earlier). Training a model on these sets forces it to hallucinate, which is detrimental to learning.

The Final Dataset Structure

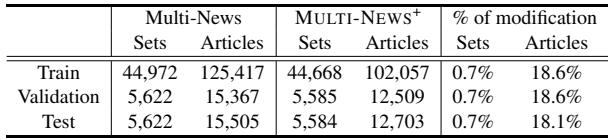

The cleansing didn’t change the train/test/validation split ratios, but it significantly reduced the word count and noise.

As shown in Table 3, while the number of sets (summary + doc clusters) remained largely the same, the number of articles dropped by roughly 18% across the board. That is nearly one-fifth of the dataset identified as garbage.

Experimental Results: Does it Work?

Removing 18% of a dataset is a bold move. There is always a risk that the model removed useful information. To prove the value of MULTI-NEWS+, the authors trained two standard summarization models—BART and T5—on both the original dataset and the cleansed dataset.

They evaluated the models using standard NLP metrics:

- ROUGE: Measures word overlap between the generated summary and the human reference.

- BERTScore: Measures semantic similarity using embeddings.

- BARTScore: Measures how likely the generated text is, given the reference.

The Verdict

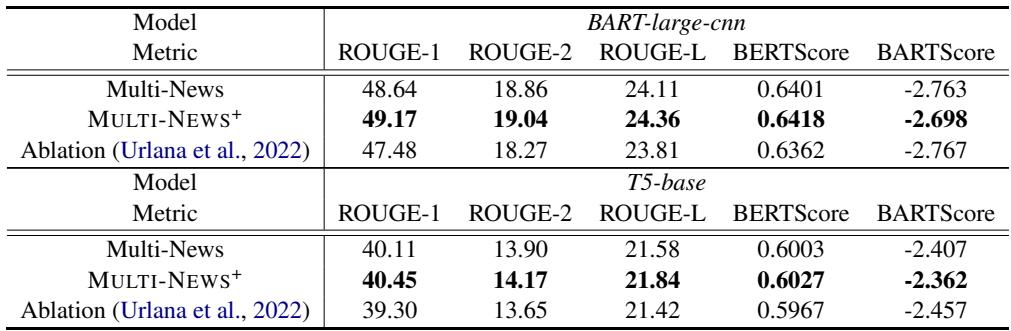

Table 2 presents the results. The rows for MULTI-NEWS+ show consistent improvements across almost every metric for both BART and T5 compared to the original Multi-News rows.

While the numeric increases (e.g., ROUGE-1 going from 48.64 to 49.17) might look small to a layperson, in the context of established NLP benchmarks, these are consistent, significant gains. It implies that the models are wasting less capacity trying to interpret noise and focusing more on synthesizing relevant facts.

Comparing to Rule-Based Methods

You might ask: “Do we really need an LLM for this? Can’t we just filter out short documents?”

The authors anticipated this question. They performed an ablation study (shown as the “Ablation” row in Table 2) using a previous method by Urlana et al. (2022), which used rule-based filtering (e.g., removing documents with low compression ratios or insufficient length).

Surprisingly, the rule-based cleaning actually hurt performance in some cases or provided negligible gains. This confirms that the “noise” in Multi-News is semantic (e.g., a full-length article about the wrong topic), not just structural (e.g., an empty file). Only an LLM with reading comprehension capabilities could detect these semantic mismatches.

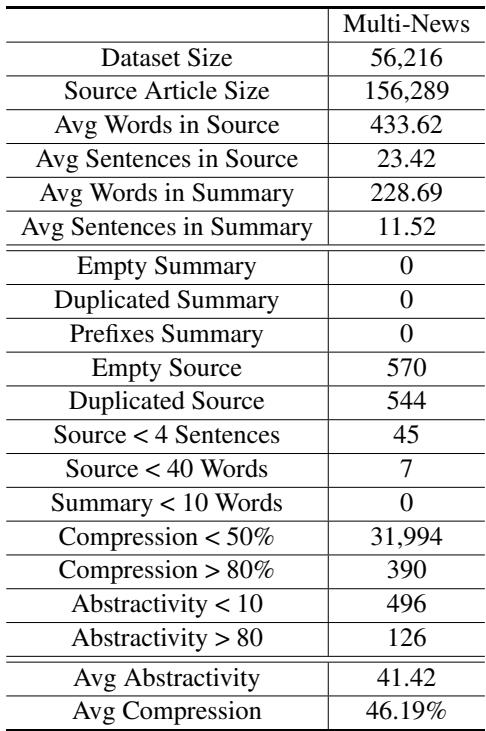

To further prove why rule-based methods failed, look at the analysis below:

Table 5 shows that standard rules like “Empty Summary” or “Duplicated Summary” found almost 0 errors. The traditional heuristics simply couldn’t catch the subtle noise that the LLM agents identified.

Discussion and Future Implications

The success of MULTI-NEWS+ has broader implications for the field of Data Science and Natural Language Processing.

The Rise of the “AI Annotator”

This paper serves as a proof-of-concept for the democratization of dataset curation. Previously, high-quality datasets were the privilege of large tech companies with budgets for human labeling farms. This method suggests that a university lab or a small startup can take a messy, web-scraped dataset and “polish” it to a professional standard for a few hundred dollars.

Impact on Few-Shot Learning

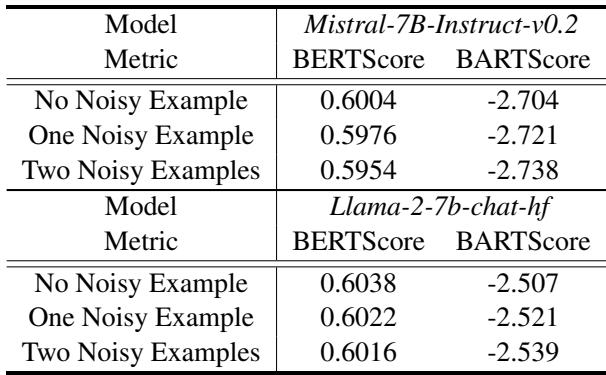

The authors also investigated how this noise affects models in a “Few-Shot” setting (where you give a model a couple of examples and ask it to perform the task).

Table 4 reveals that when LLMs (like Llama-2 or Mistral) are prompted with noisy examples (“One Noisy Example” or “Two Noisy Examples”), their performance drops compared to being shown clean examples. This reinforces that clean data isn’t just important for fine-tuning (updating weights); it’s also critical for prompting.

Future Directions

The authors propose several exciting avenues for future work:

- Weighted Voting: Instead of giving every agent an equal vote, we could use a smaller, smarter model (like GPT-4) as a “judge” or give its vote more weight than smaller models.

- Pre-screening: Instead of running expensive LLMs on every single document, we could use cheaper heuristics to flag “suspicious” documents and only send those to the LLM for verification.

- Active Crawling: Integrating agents that can browse the live web to fetch the correct content if the original scrape was bad.

Conclusion

The MULTI-NEWS+ paper reminds us that in the age of AI, data quality remains king. While the rush to build bigger models continues, this research highlights that we can unlock significant performance gains simply by cleaning the data we already have.

By combining the reasoning power of Chain-of-Thought prompting with the robustness of Majority Voting, the authors created a scalable, cost-effective pipeline for dataset hygiene. They turned a $550 investment into a permanent resource for the research community, providing a cleaner, more reliable benchmark for future summarization models.

For students and practitioners, the takeaway is clear: Before you spend weeks tweaking your model’s hyperparameters, take a look at your data. You might find that the best way to improve your AI is to let another AI clean up the mess first.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2404.09682/images/cover.png)