Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with information, from summarizing complex reports to answering open-ended questions. However, they suffer from a persistent and well-known flaw: hallucination. An LLM can confidently generate a statement that sounds plausible but is factually incorrect.

To mitigate this, the industry has largely adopted Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). In a RAG setup, the model is provided with “grounding documents”—trusted sources of evidence—and asked to generate an answer based solely on that evidence. While this helps, it does not solve the problem entirely. Models can still misinterpret the documents, blend information incorrectly, or hallucinate details not found in the text.

This creates a critical need for automated fact-checking. We need a way to verify: Does the output generated by the LLM actually align with the provided grounding document?

Currently, developers face a dilemma. They can use powerful models like GPT-4 to verify facts, which is highly accurate but prohibitively expensive and slow. Alternatively, they can use smaller, specialized models (like NLI models), which are cheap but often fail to catch subtle errors or reason across multiple sentences.

In this post, we explore a new solution presented in the paper “MiniCheck: Efficient Fact-Checking of LLMs on Grounding Documents.” The authors introduce a method to build small, efficient fact-checking models (as small as 770M parameters) that achieve GPT-4 level accuracy at 400 times lower cost. The secret lies not in a massive new architecture, but in a clever approach to generating synthetic training data.

The Problem: Fact-Checking on Grounding Documents

Before diving into the solution, we must define the specific problem being solved. The authors frame the task as fact-checking on grounding documents.

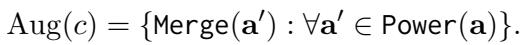

Whether a system is summarizing a news article, answering a question using retrieved Wikipedia pages, or generating a dialogue response based on meeting notes, the core primitive is the same. We have:

- A Document (\(D\)): The evidence (e.g., a retrieved snippet).

- A Claim (\(c\)): A sentence generated by the LLM.

- A Label: Binary classification. Is the claim supported (1) or unsupported (0) by the document?

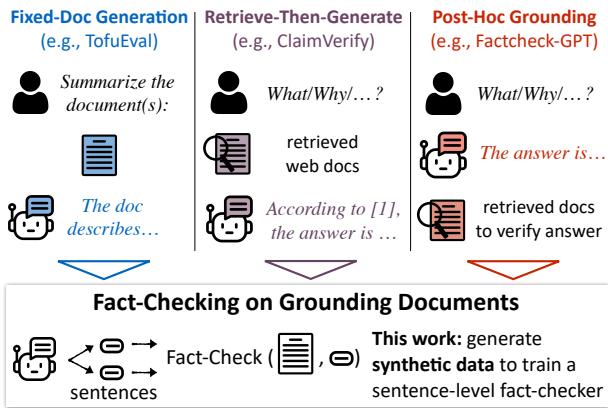

As shown in Figure 1 above, this primitive applies to various workflows:

- Fixed-Doc Generation: Summarizing a specific document.

- Retrieve-Then-Generate: RAG systems where evidence is fetched before generation.

- Post-Hoc Grounding: Where evidence is fetched after generation to verify a claim.

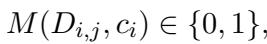

Mathematically, the goal is to build a discriminator \(M\):

Ideally, if a generated response contains multiple sentences, we verify each sentence (\(c_i\)) individually against the available documents (\(D_{i,j}\)).

Why is this hard?

Checking a sentence sounds simple, but LLM-generated sentences are often complex. A single sentence can contain multiple atomic facts. Furthermore, the evidence supporting these facts might be scattered across different parts of the grounding document.

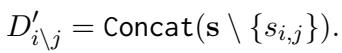

Consider the example below from the TofuEval dataset. The LLM generates a summary about airline control over weather and labor.

In Figure 2, the summary sentence contains disparate facts:

- Airlines argue weather is beyond control.

- Airlines argue labor is beyond control.

- Experts disagree regarding weather.

- Experts disagree regarding labor.

To verify this single sentence, a model must understand that the “Expert” (Trippler) agrees about the weather but disagrees about labor. This requires multi-hop reasoning—combining information from different parts of the dialogue to reach a conclusion. Most small, specialized fact-checkers fail here because they are typically trained on simple entailment datasets (like MNLI) that don’t reflect this complexity.

The Solution: Synthetic Data Generation

The authors verify that standard fine-tuning on existing datasets isn’t enough. The real breakthrough of MiniCheck is the creation of a specialized synthetic training dataset that forces the model to learn complex, multi-sentence reasoning.

Since gathering human-labeled data for this specific type of high-complexity error is expensive and unscalable, the researchers used GPT-4 to generate synthetic data. They developed two distinct pipelines: Claim-to-Doc (C2D) and Doc-to-Claim (D2C).

Method 1: Claim-to-Doc (C2D)

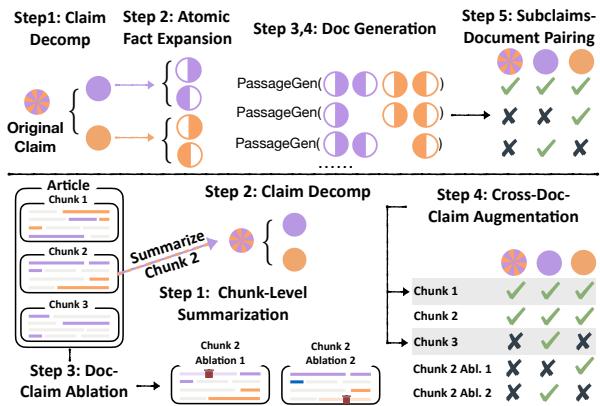

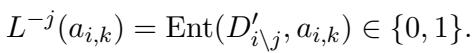

The C2D method (top of Figure 3) starts with a claim and works backward to generate a document. This approach ensures that the model learns to identify when a claim is almost supported but missing a crucial piece of evidence.

Step 1: Claim Decomposition The process begins with a human-written claim \(c\). GPT-3.5 decomposes this claim into a set of atomic facts.

Step 2: Atomic Fact Expansion This is a critical step. For each atomic fact, GPT-4 generates a pair of sentences (\(s_{i,1}, s_{i,2}\)). The prompt enforces a strict rule: the atomic fact is supported only if the information from both sentences is combined.

This forces the model to perform multi-sentence reasoning. One sentence alone is insufficient.

Step 3: Document Generation GPT-4 then writes a coherent document \(D\) that incorporates these sentence pairs. This creates a positive training example: \((D, c, \text{Label}=1)\).

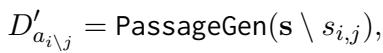

Step 4: Generating Unsupported Examples (The Trick) To create negative examples (where the claim is unsupported), the system generates a new document \(D'\) by removing one of the sentences from the necessary pair.

Because the atomic fact required both sentences to be true, removing one makes the document insufficient to support the claim. This teaches the model to look for complete evidence.

Step 5: Subclaim Matching Finally, the system mixes and matches different subsets of atomic facts to create various “subclaims.”

This results in a rich dataset where the same document might support one version of a claim but not another, depending on which atomic facts are included.

Method 2: Doc-to-Claim (D2C)

While C2D is excellent for teaching reasoning, the documents are synthetic. To ensure the model adapts to real-world writing styles, the authors introduce the Doc-to-Claim (D2C) method (bottom of Figure 3).

Step 1: Chunk-Level Summarization The pipeline takes a real human-written document (e.g., a news article) and splits it into chunks. GPT-4 generates a summary for each chunk. We assume these summaries are factually consistent (Label = 1).

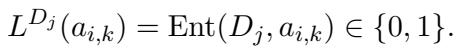

Step 2: Ablation (Removing Evidence) To create negative examples, the system iteratively removes sentences from the original document chunk.

The system then checks (using GPT-4 as an oracle) if the atomic facts in the summary are still supported by this ablated document.

If removing a sentence causes a fact to lose support, that creates a hard negative example: the summary looks related to the text, but the specific evidence is gone.

Step 3: Cross-Document Augmentation The system also tests the summary against other chunks of the same document. This is challenging because a summary of Paragraph 1 might be partially supported by Paragraph 2, or not at all. This helps the model distinguish between “on-topic” and “factually supported.”

The Resulting Data

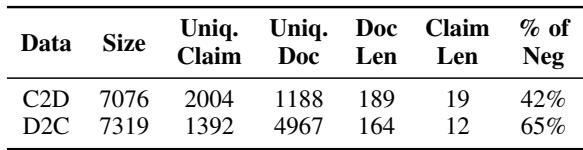

By combining these two methods, the authors created a high-quality synthetic dataset.

As seen in Table 1, the dataset is balanced and contains roughly 14,000 examples. This is relatively small compared to massive NLI datasets, but the density of reasoning required makes it highly effective.

The Model: MiniCheck

The authors used this synthetic data to fine-tune three different base models:

- MiniCheck-RBTA: RoBERTa-Large (355M parameters).

- MiniCheck-DBTA: DeBERTa-v3-Large (435M parameters).

- MiniCheck-FT5: Flan-T5-Large (770M parameters).

They also combined their synthetic data with a small subset (21k examples) of the ANLI dataset, which is a standard benchmark for natural language inference.

LLM-AGGREFACT: A Unified Benchmark

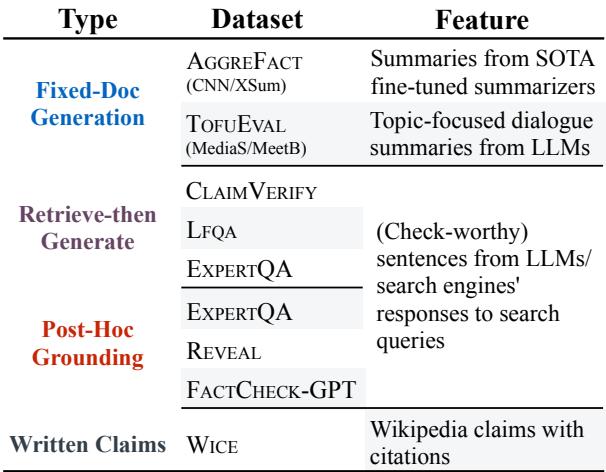

To rigorously test their models, the authors needed a benchmark that covered the diverse ways LLMs are used. They introduced LLM-AGGREFACT, a unification of 10 existing datasets.

This benchmark is comprehensive. It includes:

- Summarization checks (CNN/DM, XSum).

- Dialogue summarization (TofuEval).

- RAG correctness (ClaimVerify, ExpertQA).

- Hallucination detection (Reveal, FactCheck-GPT).

This diversity ensures that a model performing well on LLM-AGGREFACT isn’t just memorizing one specific type of prompt but is actually learning to verify facts.

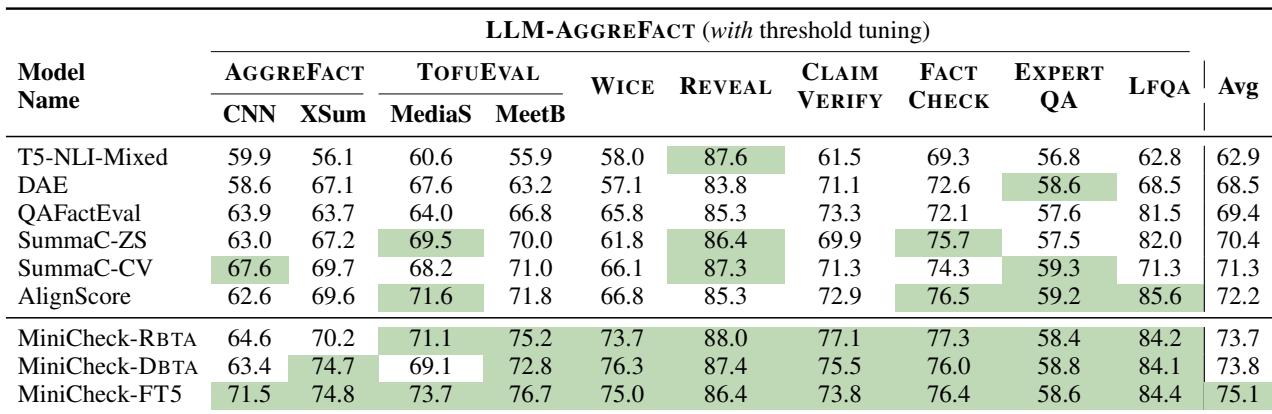

Experiments and Results

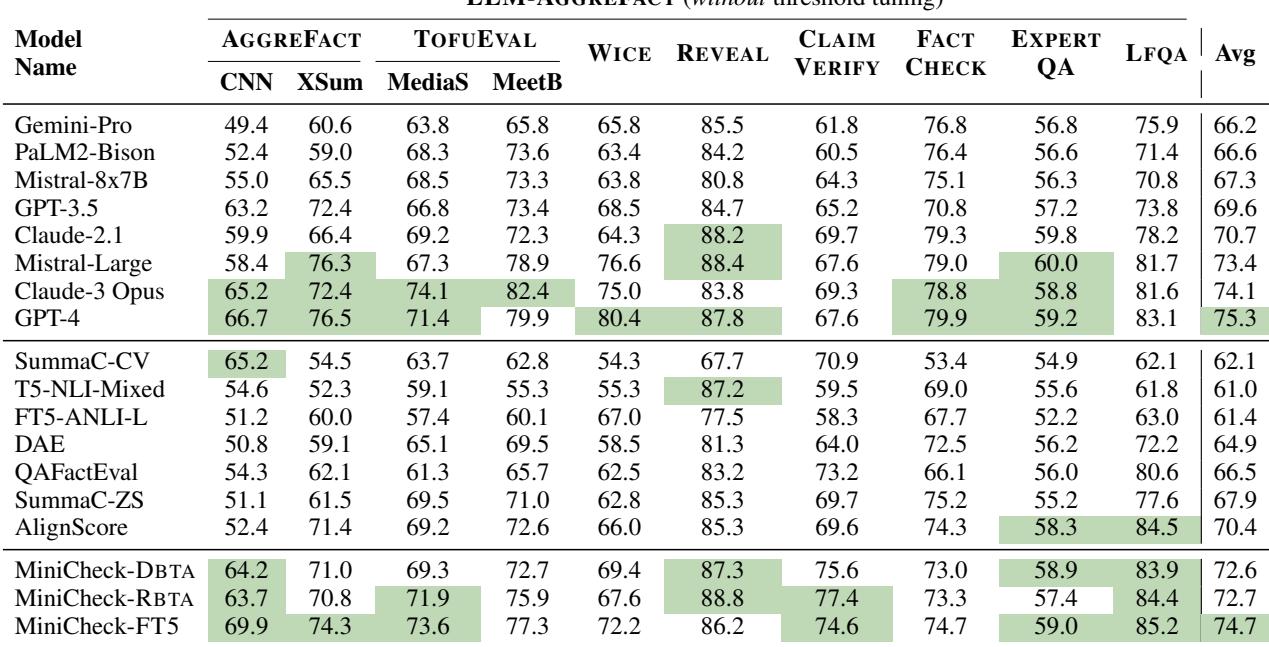

The results are striking. The authors compared MiniCheck against state-of-the-art specialized models (like AlignScore and SummaC) and massive LLMs (GPT-4, Claude 3, Gemini).

Accuracy

Table 2 highlights the main findings:

- MiniCheck-FT5 (74.7%) matches GPT-4 (75.3%). The difference is statistically negligible.

- MiniCheck outperforms other specialized models. It beats AlignScore (the previous state-of-the-art for specialized models) by over 4 percentage points.

- Model size isn’t everything. Note that

T5-NLI-Mixed(an 11B parameter model) scores significantly lower (61.0%) than MiniCheck-FT5 (770M parameters). This proves that the quality of the synthetic training data matters more than raw parameter count.

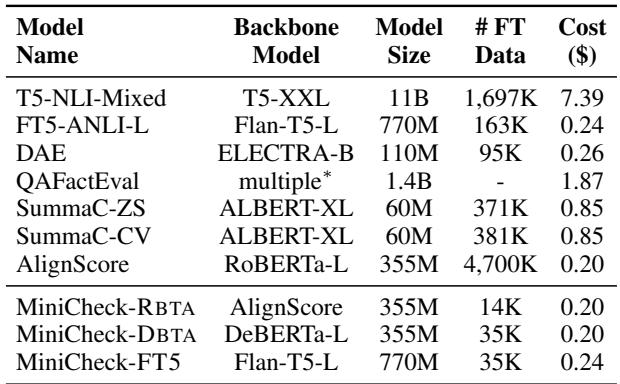

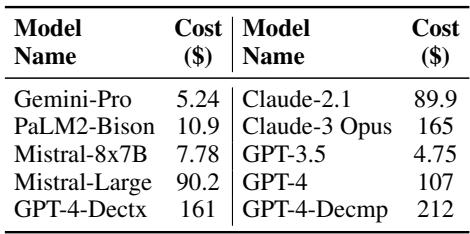

The Cost Factor

The most compelling argument for MiniCheck is economic.

Comparing Table 3 and Table 4 reveals a massive disparity:

- GPT-4 Cost: ~$107.00 to evaluate the benchmark.

- MiniCheck-FT5 Cost: ~$0.24 to evaluate the benchmark.

This represents a 400x reduction in cost. For a company deploying a RAG system that processes thousands of queries a day, moving from GPT-4-based verification to MiniCheck-FT5 could mean saving hundreds of thousands of dollars annually.

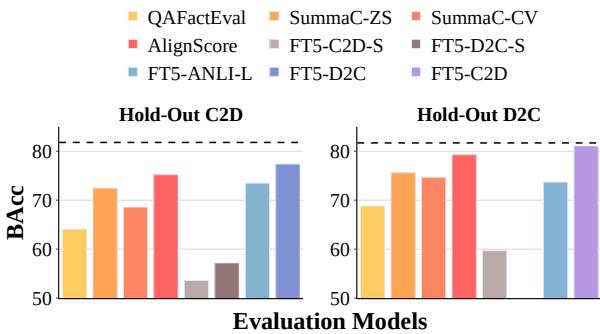

Does the Synthetic Data Generalize?

One valid concern with synthetic data is overfitting—the model might get really good at checking synthetic claims but fail on real ones.

Figure 5 shows the results on held-out test sets. Crucially, the models trained on C2D data perform exceptionally well on D2C data, and vice versa. This “cross-pollination” success suggests that the models have learned the underlying skill of fact verification rather than just memorizing synthetic patterns.

An ablation study further confirmed this importance:

As shown in Table 6, without the new synthetic data, the model’s performance collapses from ~75% to ~60%, proving that the ANLI data alone is insufficient for this task.

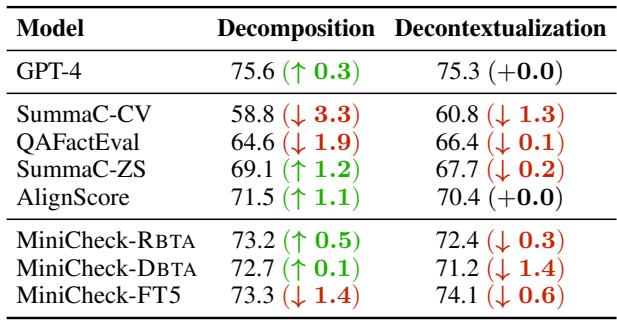

Rethinking Fact-Checking Pipelines

The paper also challenges some common assumptions in the field, specifically regarding Claim Decomposition and Decontextualization.

Is Decomposition Necessary?

Previous research suggested that to check a complex sentence, you must first break it down into atomic facts (Decomposition) and check each one separately.

Table 5 reveals a surprising result: Decomposition is largely unnecessary for capable models.

- GPT-4 gained almost no benefit (+0.3%).

- MiniCheck-FT5 actually performed slightly worse with decomposition (-1.4%).

Detailed results for decomposition can be seen here:

This is excellent news for efficiency. Decomposition requires extra LLM calls to break the sentence down, increasing latency and cost. MiniCheck demonstrates that a model trained on complex synthetic data (which inherently includes atomic fact reasoning) can verify the whole sentence in one pass.

What about Decontextualization?

Decontextualization involves rewriting a sentence so it stands alone (e.g., replacing “He said” with “The CEO said”). The study found that while this is theoretically useful, it didn’t yield significant performance gains on this benchmark, likely because the retrieval step in RAG systems usually preserves enough context.

Conclusion

The “MiniCheck” paper presents a significant step forward in making safe AI accessible and affordable. By cleverly reverse-engineering the fact-checking process to generate high-quality synthetic training data, the authors created a system that rivals the most powerful LLMs in existence while being small enough to run on modest hardware.

Key Takeaways:

- Synthetic data is a superpower: When real labeled data is scarce, creating challenging synthetic data (via C2D and D2C methods) can train highly effective models.

- Efficiency without compromise: MiniCheck-FT5 matches GPT-4’s accuracy for fact-checking grounding documents but is 400x cheaper.

- Simplicity wins: Complex pipelines involving claim decomposition may not be necessary if the underlying model is trained to handle multi-fact reasoning natively.

For students and researchers, this work highlights that we don’t always need bigger models to solve hard problems—sometimes, we just need better data. The release of the LLM-AGGREFACT benchmark also provides a valuable standard for measuring progress in the fight against hallucinations.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2404.10774/images/cover.png)