In the rapidly evolving world of Natural Language Processing (NLP), text embedding models are the unsung heroes. They transform text into vector representations—lists of numbers that capture semantic meaning—serving as the engine for information retrieval (IR) and Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG).

However, there is a persistent bottleneck in this engine: the context window.

Most popular embedding models, such as BERT-based architectures, are restricted to a short context window, typically 512 tokens. In real-world applications—like searching through legal contracts, summarizing long meeting transcripts, or indexing entire Wikipedia articles—512 tokens is simply not enough. When the input exceeds this limit, the text is usually truncated, leading to a massive loss of information.

The obvious solution is to train new models with longer context windows from scratch. But this is prohibitively expensive. For instance, training the BGE-M3 model (which supports 8k context) required 96 A100 GPUs.

This brings us to a compelling research paper: “LONGEMBED: Extending Embedding Models for Long Context Retrieval.” The authors propose a more efficient path. Instead of training from scratch, can we take existing highly capable models and “stretch” their capacity to handle long contexts (up to 32,768 tokens)?

In this deep dive, we will explore how they constructed a new benchmark to measure this capability, the mathematical tricks used to extend context windows without expensive retraining, and why Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) might be the future of long-context NLP.

The Problem with Current Evaluation

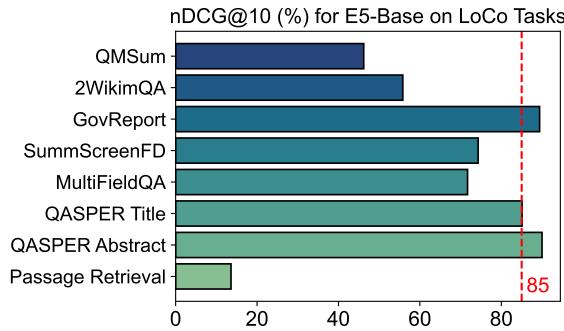

Before we can fix the context limit, we need to measure it. You might assume that we already have benchmarks for retrieval, such as BEIR or LoCo. However, the authors argue that these existing benchmarks have fatal flaws when it comes to evaluating long-context capabilities.

The two main issues are:

- Limited Document Length: Many datasets in benchmarks like BEIR average fewer than 300 words per document. You can’t test long-context capability if the documents are short.

- Biased Information Distribution: In many “long” document datasets, the answer to a query is often located at the very beginning of the document.

This second point is crucial. If an embedding model only looks at the first 512 tokens and ignores the rest, but the answer is in those first 512 tokens, the model will get a high score. It gives the illusion of long-context understanding without doing the work.

As shown in Figure 2 above, the E5_Base model, which strictly supports only 512 tokens, achieves over 85% accuracy on tasks like GovReport. This indicates that the “key” information in these tasks is clustered at the start, making them poor proxies for true long-context evaluation.

Introducing LONGEMBED

To solve this, the researchers introduced LONGEMBED, a robust benchmark designed to ensure that models actually read the whole text. It consists of two categories of tasks: Synthetic and Real-World.

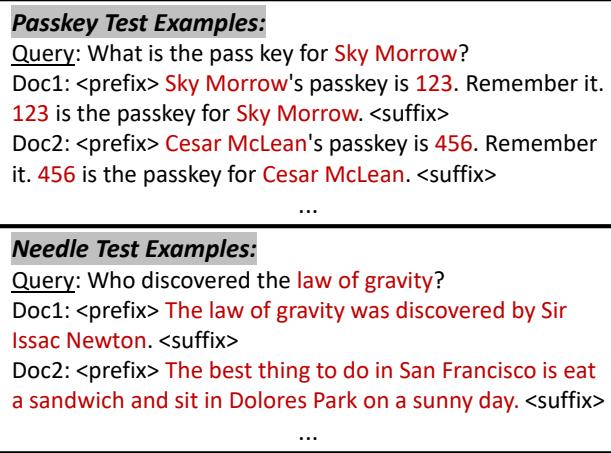

1. Synthetic Tasks: Precision Testing

Synthetic tasks allow researchers to control exactly where the answer is hidden (the “needle”) and how long the document is (the “haystack”).

- Needle-in-a-Haystack: The model must retrieve a document where a random fact (e.g., “The best thing to do in San Francisco is eat a sandwich”) is inserted into a long essay.

- Personalized Passkey Retrieval: The model must find a document containing a specific passkey for a specific person, hidden among garbage text.

As illustrated in Figure 3, these tasks force the model to encode the specific “needle” regardless of whether it appears at position 100 or position 30,000.

2. Real-World Tasks

To ensure practical applicability, LONGEMBED includes four real datasets where answers are dispersed throughout the text:

- NarrativeQA: Questions about long stories (literature/film).

- 2WikiMultihopQA: Requires reasoning across different parts of Wikipedia articles.

- QMSum: Meeting summarization.

- SummScreenFD: Screenplay summarization.

By combining these, the authors created a testing ground where a model cannot “cheat” by only reading the introduction.

The Core Method: Stretching the Window

The heart of this paper is the exploration of Context Window Extension. This involves taking a pre-trained model (trained on short texts) and applying strategies to make it process long texts.

The authors categorize embedding models into two families based on how they handle positions:

- APE (Absolute Position Embedding): Models like BERT or the original E5, which assign a specific learned vector to position 1, position 2, etc., up to 512.

- RoPE (Rotary Position Embedding): Modern models like LLaMA or E5-Mistral, which encode position by rotating the vector space.

Strategy 1: The Divide-and-Conquer Approach

The simplest method is Parallel Context Windows (PCW).

- How it works: You chop a long document (e.g., 4000 tokens) into chunks that fit the model (e.g., 512 tokens).

- Process: You feed each chunk into the model independently to get an embedding. Then, you average the embeddings of all chunks to represent the whole document.

- Pros/Cons: It’s easy to implement, but it breaks the semantic relationship between chunks. The model can’t “pay attention” to tokens across the boundaries of the chunks.

Strategy 2: Position Reorganization (For APE Models)

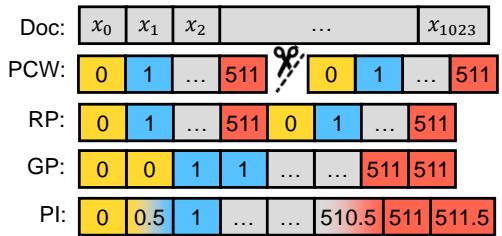

If we want to process the whole sequence at once, we need to deal with the position IDs. An APE model only knows position IDs 0 through 511. What happens when we hit token 512?

The authors explore reusing the existing position embeddings:

- Grouped Positions (GP): You slow down the position counter. Tokens 0 and 1 both get Position ID 0. Tokens 2 and 3 get Position ID 1. This stretches the 512 IDs to cover 1024 tokens.

- Recurrent Positions (RP): You loop the IDs. Token 512 gets ID 0. Token 513 gets ID 1.

- Linear Interpolation (PI): Instead of integers, you map positions to decimals. If you want to double the context, you divide the position indices by 2. Token 0 stays at 0. Token 1 becomes 0.5. Token 1024 becomes 512. Since the model doesn’t have an embedding for “0.5,” you mathematically interpolate between the embedding for 0 and 1.

Figure 4 (Left) visualizes this. Notice how GP creates “steps” in position IDs, while RP creates a “sawtooth” pattern.

Further Tuning: The authors found that for APE models, just manipulating IDs wasn’t enough. They achieved the best results by fine-tuning the model. They freeze the original model parameters and only train the position embeddings (see Figure 4, Right). This allows the model to learn how to handle these new, stretched positions without forgetting its original training (“catastrophic forgetting”).

Strategy 3: RoPE Extensions (The Modern Way)

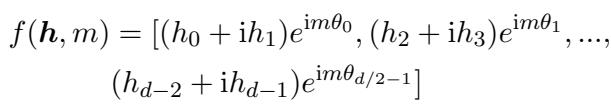

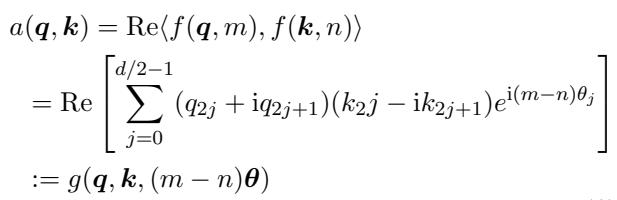

Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE) is mathematically more elegant for extensions because it encodes relative positions through rotation matrices.

The RoPE function rotates a vector based on its position \(m\):

The attention score between a query and a key depends on the distance between them \((m-n)\):

Because RoPE relies on rotation frequencies (\(\theta\)), we can extend context by manipulating these frequencies:

- NTK-Aware Interpolation (NTK): Based on Neural Tangent Kernel theory. Instead of linearly squashing all positions (which hurts the model’s ability to distinguish close-by tokens), NTK scales high frequencies less and low frequencies more. This preserves local details while allowing for longer global context.

- SelfExtend (SE): This method uses a normal context window for immediate neighbors (to keep local accuracy high) and a grouped window for distant tokens. It requires no training and works surprisingly well.

Experiments & Results

The authors tested these strategies extensively on the LONGEMBED benchmark.

1. Does Extension Work?

Yes, dramatically.

As seen in the heatmaps below (Panel b), standard models fail completely (white/yellow cells) as input length increases. However, the extended models (like E5-Mistral + NTK) maintain high accuracy (green cells) even up to 32k tokens.

Look at Panel (c) in Figure 1. The blue line (E5-Mistral) drops as context grows. But the dashed gray line (E5-Mistral + NTK) stays high. This proves that a training-free strategy (NTK) can unlock massive context capabilities in RoPE models.

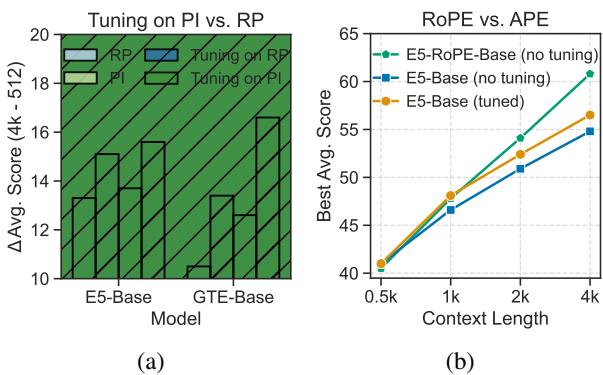

2. APE vs. RoPE: The Showdown

One of the paper’s most significant contributions is a direct comparison between APE and RoPE architectures.

To make it fair, the authors trained a new model, E5-RoPE_Base, from scratch using the exact same data and procedure as the original E5_Base (APE), but swapping the position embedding for RoPE.

The Finding: RoPE is significantly better at length extrapolation.

In Figure 6 (b), compare the blue bars (Original E5) with the gray bars (E5-RoPE). Without any extra work, the RoPE version handles longer contexts better. When extended, RoPE models maintain their performance far better than their APE counterparts.

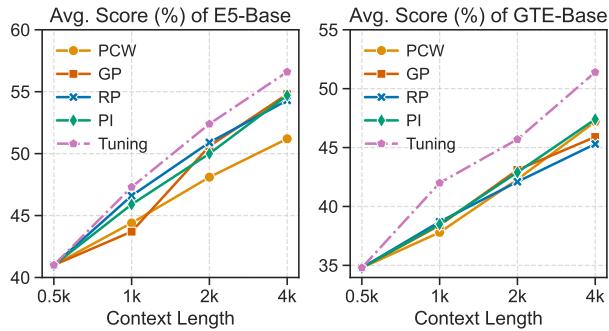

3. To Tune or Not to Tune?

For APE-based models (like the standard E5 or GTE), “Plug-and-Play” methods (like just changing the position IDs) work okay, but fine-tuning yields the best results.

Figure 5 shows that the “Tuning” line (purple/pink) is consistently above the others for both E5 and GTE. This suggests that if you are stuck with an older BERT-based model, a little bit of fine-tuning on the position embeddings is worth the compute.

Conclusion & Implications

The “LONGEMBED” paper offers a blueprint for the NLP community. We don’t always need massive compute clusters to train new models for long-context tasks.

Key Takeaways for Students and Practitioners:

- Don’t Trust Short Benchmarks: If you are building a RAG system for long documents, ensure you evaluate your embedding model on a benchmark like LONGEMBED, not just standard retrieval tasks.

- RoPE is King: If you are choosing a backbone for a new model, use Rotary Position Embeddings. They offer superior flexibility for context extension later on.

- Free Upgrades: If you are using a RoPE-based model (like E5-Mistral), you can likely extend its context window to 32k tokens without training by using NTK-Aware Interpolation or SelfExtend.

- Reviving Old Models: Even older APE models can be upgraded to handle 4k+ tokens with efficient fine-tuning of their position embeddings.

This research effectively democratizes long-context retrieval, allowing developers to process books, manuals, and codebases using existing open-source models, simply by applying the right mathematical transformations.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2404.12096/images/cover.png)