Introduction

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”

This famous quote by Peter Drucker rings especially true in the world of medical communication. We live in an era where reliable medical knowledge is crucial for public health. From Wikipedia articles to the Merck Manuals, and from cutting-edge research papers to patient pamphlets, the dissemination of health information is constant.

However, access to information does not equate to understanding. Medical texts are notoriously difficult to digest. They are dense, technical, and filled with specialized terminology that can alienate the very people they are meant to help—patients and non-experts.

To make medical texts more accessible, we first need a reliable way to measure how hard they are to read. But here lies the problem: traditional readability metrics, which were designed for general English (like news articles or school textbooks), often fail when applied to the medical domain.

In this post, we will dive deep into a paper titled “MEDREADME: A Systematic Study for Fine-grained Sentence Readability in Medical Domain.” This research introduces a groundbreaking dataset and a new methodology for assessing readability. We will explore why medical sentences are so hard to parse, how researchers categorized “jargon” based on Google search results, and how a simple modification to existing math formulas can drastically improve our ability to predict readability.

The Problem with Traditional Metrics

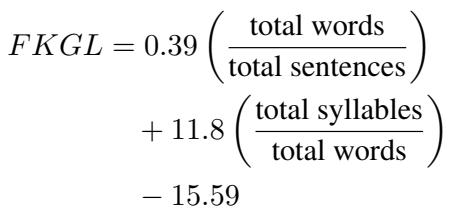

Before we explore the solution, we need to understand the flaw in the current tools. You might be familiar with readability tests like the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL). These formulas typically rely on surface-level features: the number of syllables in a word and the number of words in a sentence.

The logic is simple: long words and long sentences are hard to read.

\[ \begin{array} { r } { F K G L = 0 . 3 9 \left( \frac { \mathrm { \ t o t a l ~ w o r d s } } { \mathrm { t o t a l ~ s e n t e n c e s } } \right) } \\ { + 1 1 . 8 \left( \frac { \mathrm { t o t a l ~ s y l l a b l e s } } { \mathrm { \ t o t a l ~ w o r d s } } \right) } \\ { - 1 5 . 5 9 } \end{array} \]

However, in the medical field, complexity isn’t always about length. A short sentence packed with obscure medical terms (jargon) can be much harder to understand than a long, descriptive sentence using common words. Because traditional metrics ignore the meaning and familiarity of specific terms, they often misclassify the difficulty of medical texts.

To fix this, the researchers realized they needed better data. They needed a dataset that didn’t just look at sentences, but looked at the specific words inside them that cause confusion.

Introducing MEDREADME

The researchers constructed MEDREADME, a dataset consisting of 4,520 sentences. These sentences were sourced from 15 diverse medical resources, ranging from highly technical research abstracts (like PLOS Pathogens) to encyclopedias intended for a broader audience (Merck Manuals and Wikipedia).

What makes this dataset unique is its granularity. It includes:

- Sentence-level readability ratings: Annotated by humans using the CEFR scale (a standard for language proficiency).

- Fine-grained span annotations: Specific words or phrases highlighted as difficult, categorized by why they are difficult.

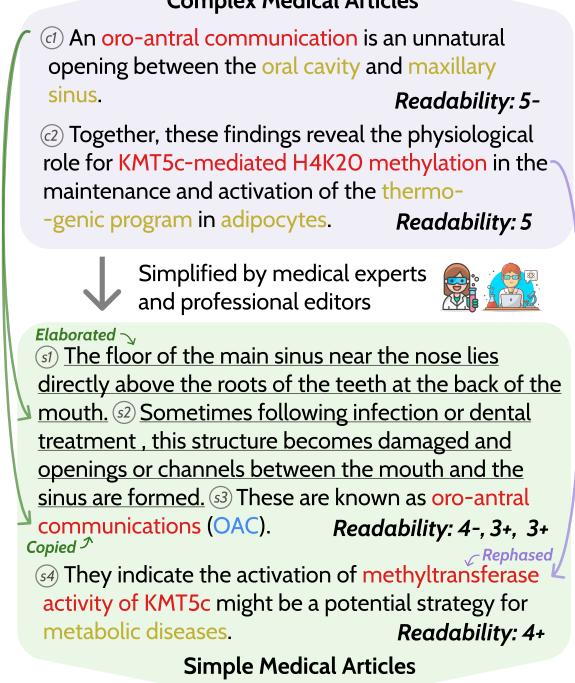

As shown in Figure 1 above, the dataset tracks how complex sentences are transformed into simple ones. Notice the transition from a “Complex Medical Article” to a “Simple Medical Article.” The researchers didn’t just rate the sentences; they tracked the specific “jargon” spans (like “oro-antral communication”) to see if they were deleted, explained, or kept in the simplified version.

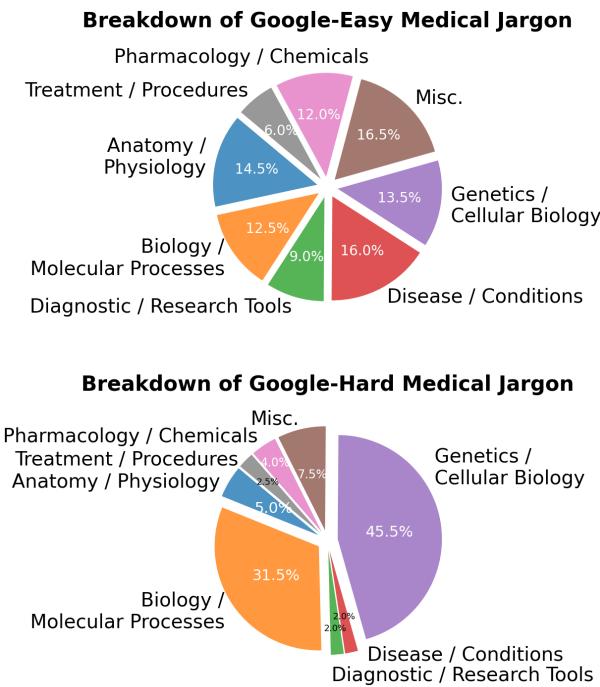

A New Taxonomy: “Google-Easy” vs. “Google-Hard”

One of the most innovative contributions of this paper is how it categorizes jargon. In the past, words were often just binary: “complex” or “not complex.”

The authors argue that in the modern age, difficulty is relative to searchability. Most people check health information online. Therefore, they introduced two novel categories:

- Google-Easy: Medical terms that are technical but can be easily understood after a quick Google search (e.g., “Schistosoma mansoni”). The search results usually provide a clear definition, images, or a “Knowledge Panel.”

- Google-Hard: Terms that require extensive research to understand, even after Googling. These might be complex multi-word expressions (e.g., “processive nucleases”) where search results are dense academic papers rather than simple summaries.

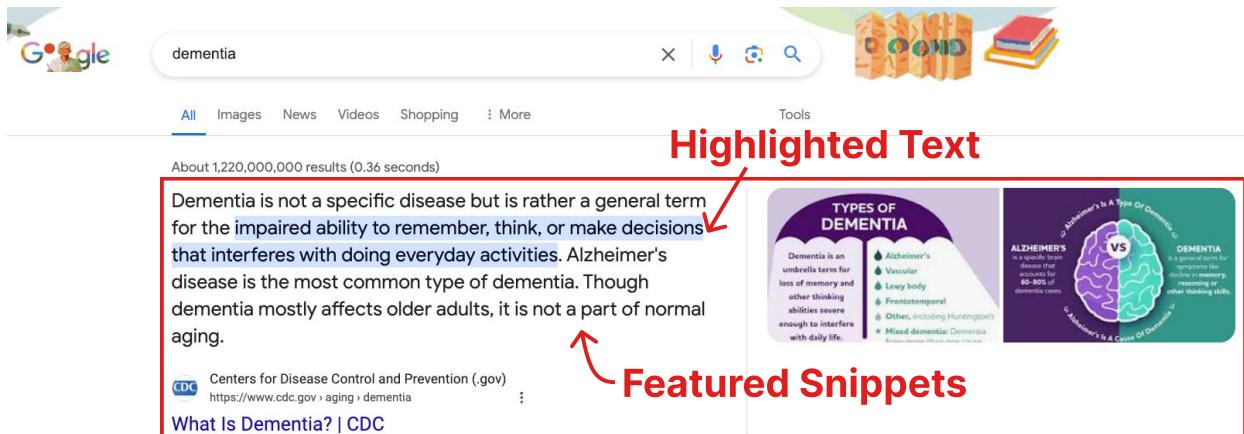

Figure 6 illustrates why a term might be “Google-Easy.” When a search engine provides a “Knowledge Panel” (the box on the right) or a “Featured Snippet” (the answer at the top), the cognitive load on the reader drops significantly. The researchers found that “Google-Easy” terms are far more likely to have these visual aids compared to “Google-Hard” terms.

Why Are Medical Texts So Hard?

With the dataset built, the researchers performed a data-driven analysis to pinpoint exactly what makes medical text difficult. They analyzed 650 linguistic features, but the results pointed to one dominant factor: Jargon.

Jargon vs. Sentence Length

While traditional metrics emphasize sentence length, the MEDREADME analysis shows that jargon is a stronger predictor of difficulty in this domain.

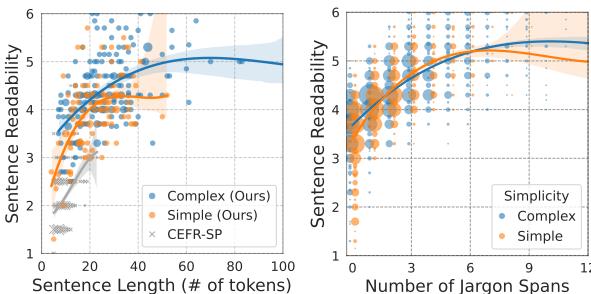

Look at the graphs in Figure 3.

- Left Graph: Shows the relationship between readability and sentence length. You can see the correlation, but notice how the “Complex” and “Simple” lines separate significantly only after the sentences get quite long.

- Right Graph: Shows the relationship between readability and the number of jargon spans. The slope is steeper and the distinction is clearer. The more jargon spans in a sentence, the harder it is to read, almost linearly.

This confirms that while length matters, the density of specialized terminology is the critical bottleneck for comprehension.

The Domain of Difficulty

Not all jargon is created equal. The researchers broke down “Google-Easy” and “Google-Hard” terms by their medical sub-domain.

As seen in Figure 4, Genetics and Cellular Biology (the blue sections) dominate the “Google-Hard” category. These fields deal with abstract, microscopic concepts that are harder to visualize and less likely to have simple consumer-facing explanations on the web. In contrast, terms related to diseases or anatomy are often “Google-Easy” because they are more concrete and commonly searched.

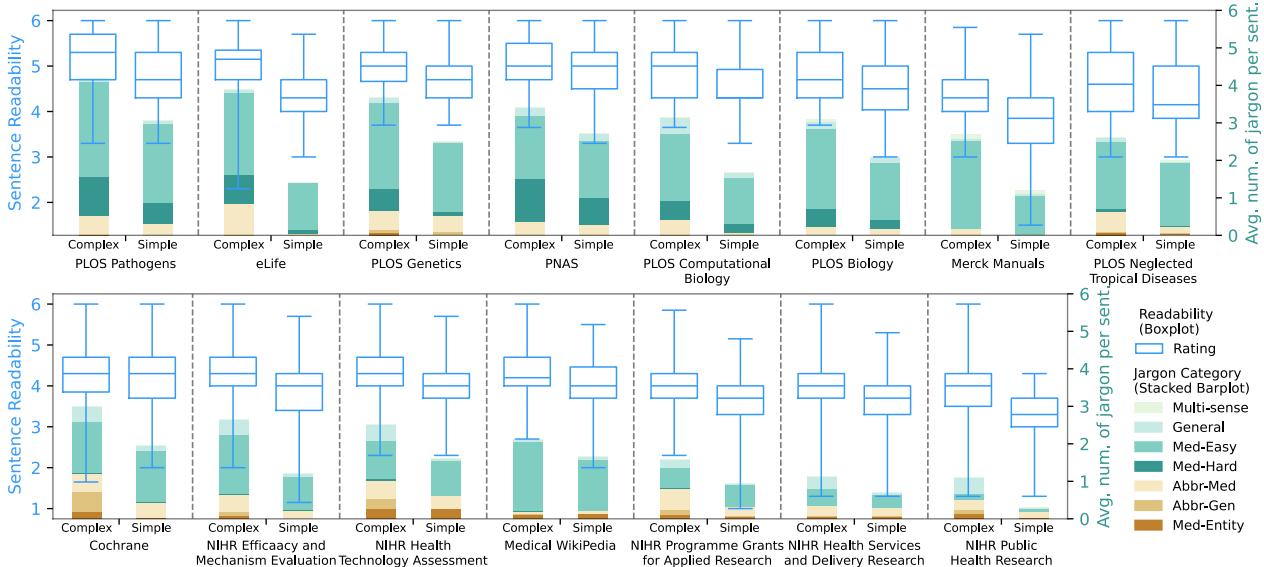

Variability Across Sources

Another fascinating finding was the inconsistency of “simplified” texts. We often assume that if a text is labeled “plain language summary,” it must be easy to read.

Figure 2 reveals a messy reality. The blue boxplots show the readability range. While “Simple” versions (right side of each pair) are generally easier than “Complex” versions (left side), the baseline varies wildly.

- Merck Manuals (far right) are consistently readable.

- PLOS Pathogens (far left), even in its simplified version, remains highly difficult—harder than the complex versions of other sources!

This suggests that “simplification” is subjective and highly dependent on the target audience of the specific journal or platform.

Improving Readability Metrics

The analysis provided a clear roadmap: if jargon is the main culprit, our formulas need to account for it.

The “-Jar” Improvement

The researchers proposed a simple modification to existing unsupervised metrics (like FKGL, ARI, and SMOG). They added a single feature: the number of jargon spans (\(\#Jargon\)).

For example, the classic FKGL formula is updated to FKGL-Jar:

\[ \mathrm { F K G L \mathrm { - } J a r } = \mathrm { F K G L } + \alpha \times \# \mathrm { J a r g o n } , \]

Here, \(\alpha\) is a weight parameter tuned on the dataset. This simple addition integrates the semantic difficulty (the jargon) with the syntactic difficulty (sentence length).

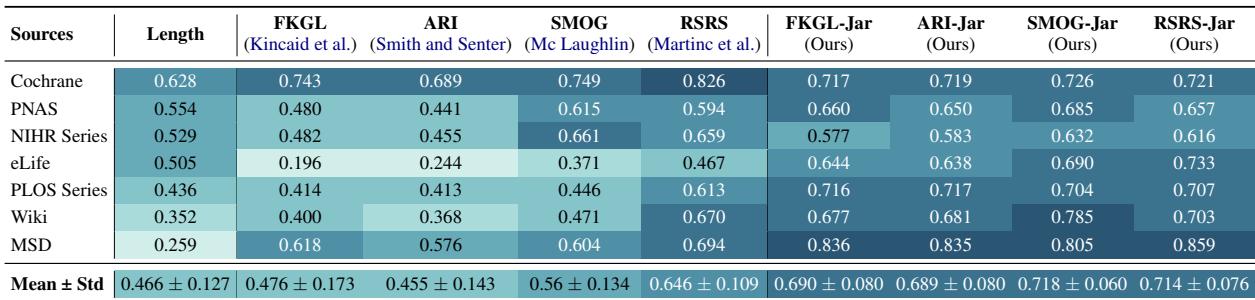

The Results

The impact of this change was significant. The researchers compared standard metrics against their “Jar” enhanced versions.

Table 4 shows the Pearson correlation between the metric scores and human judgment (higher is better).

- FKGL had a correlation of roughly 0.476.

- FKGL-Jar jumped to 0.690.

- SMOG went from 0.56 to 0.718.

By simply counting the jargon, the formulas became much better at predicting what a human would find difficult.

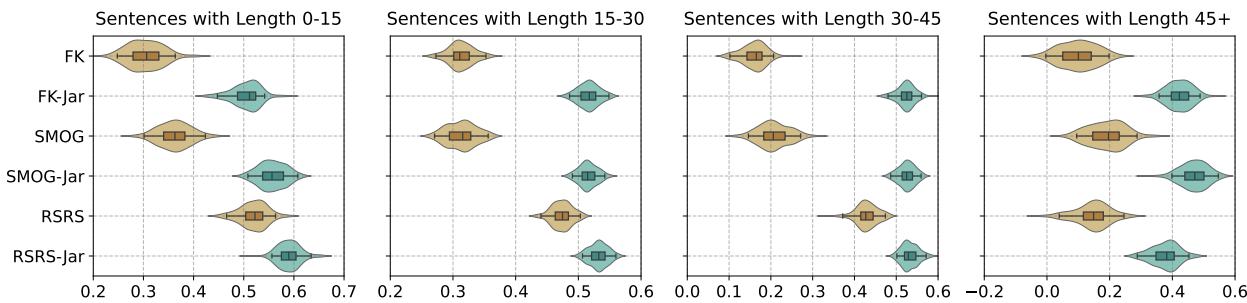

Stability Across Lengths

Furthermore, adding the jargon term made the metrics more stable across different sentence lengths.

Figure 5 shows the confidence intervals for the correlations. The teal distributions (representing the new “-Jar” metrics) are consistently higher (better correlation) and tighter (more stable) than the brown distributions (standard metrics), regardless of whether the sentence is short (0-15 words) or long (45+ words).

Automating Jargon Identification

To use the “FKGL-Jar” formula in the real world, you need to know how many jargon terms are in a sentence. Manually counting them is impossible at scale.

The researchers treated this as a Named Entity Recognition (NER) task. They trained deep learning models (specifically BERT and RoBERTa) to automatically scan sentences and identify spans of text that qualify as jargon.

They tested various models, including those pre-trained specifically on biomedical text (BioBERT, PubMedBERT).

Model Performance

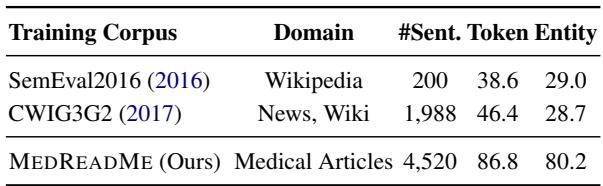

The researchers evaluated how well these models could identify the 7 different categories of complex spans (like Google-Easy, Google-Hard, Abbreviations, etc.).

Table 9 highlights the necessity of the MEDREADME dataset. When models were trained on general domain data (like Wikipedia or News from previous competitions), they failed miserably on medical text (F1 scores around 38-46%). However, models trained on MEDREADME achieved an F1 score of 86.8%.

This proves that medical readability is a specialized domain that requires specialized training data. You cannot simply apply a generic “complex word identifier” to a clinical trial summary and expect accurate results.

Conclusion

The MEDREADME study fundamentally shifts how we should approach medical text simplification. It moves us away from the outdated idea that “short words = easy reading” and acknowledges the nuance of vocabulary.

Key Takeaways:

- Context Matters: A medical term isn’t just “hard”; it’s “Google-Easy” or “Google-Hard” depending on the digital ecosystem surrounding it.

- Jargon is King: The density of technical terminology is the single biggest predictor of reading difficulty in healthcare, outweighing sentence length.

- Simple Fixes Work: We don’t always need massive black-box models. Adding a simple jargon count to 50-year-old formulas like FKGL makes them highly effective again.

- Data is Crucial: General-purpose NLP models fail in medicine. High-quality, domain-specific annotations like MEDREADME are essential for training AI to help patients.

By measuring readability more accurately, we can build better tools for doctors, editors, and AI to simplify medical text. Ultimately, this leads to a world where patients can better understand their health, make informed decisions, and navigate the complex landscape of modern medicine with confidence.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.02144/images/cover.png)