Imagine you have trained a state-of-the-art Large Language Model (LLM). It speaks fluent English, codes in Python, and understands complex reasoning. But there is a problem: it believes the Prime Minister of the UK is still Boris Johnson, or it doesn’t know about a major geopolitical event that happened yesterday.

This is the “static knowledge” problem. Once an LLM is trained, its knowledge is frozen in time. Retraining these massive models from scratch every time a fact changes is financially and computationally impossible. This has led to the rise of Model Editing—techniques designed to surgical update specific facts in an LLM without breaking its general capabilities.

However, most current editing methods face a critical flaw: they work well for one or two edits, but they crumble when you try to make thousands of edits over time. This scenario, known as Lifelong Knowledge Editing, is the holy grail of maintaining up-to-date AI.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into RECIPE (RetriEval-augmented ContInuous Prompt lEarning), a new framework presented by researchers from East China Normal University and Alibaba Group. RECIPE proposes a clever solution that bypasses the need to mess with the model’s weights directly, instead using a retrieval system and “continuous prompts” to inject knowledge on the fly.

The Problem: Why Lifelong Editing is Hard

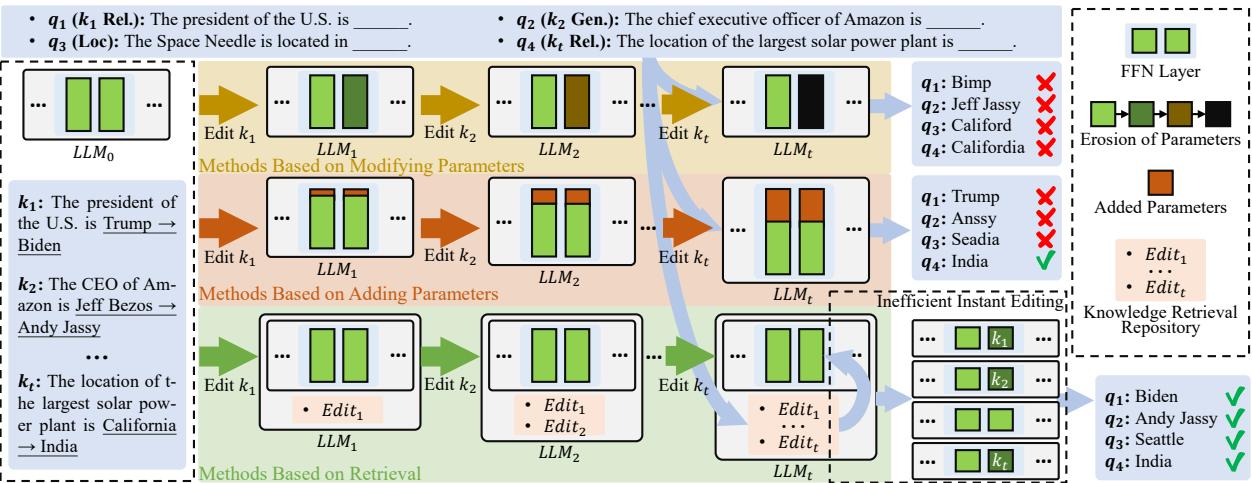

To understand why RECIPE is necessary, we first need to look at the landscape of Model Editing. Generally, previous approaches fall into three categories:

- Modifying Parameters: These methods (like ROME or MEMIT) locate the specific neurons responsible for a fact and mathematically alter the weights to change that fact.

- Adding Parameters: These methods (like T-Patcher) stick new neurons onto the model to handle the new information.

- Retrieval-Based Methods: These keep the model frozen but use an external database to fetch correct answers and feed them to the model during inference.

While these work for batch updates, they struggle in a “lifelong” setting where edits arrive sequentially over months or years.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the cracks begin to show as the number of edits (\(t\)) increases:

- Parameter Erosion: Methods that modify parameters suffer from “catastrophic forgetting.” As you continuously tweak the weights (\(k_1, k_2, \dots, k_t\)), the accumulated changes start to conflict, eventually degrading the model’s performance on previous edits and general tasks. The model essentially becomes confused.

- Parameter Bloat: Methods that add parameters avoid destroying old weights, but they become inefficient. If you add a new neuron for every new fact, your model grows indefinitely, slowing down inference speed until it becomes unusable.

- The Retrieval Promise: Retrieval-based methods (the bottom path in Figure 1) seem ideal. They store facts in a separate repository (like a database). The LLM remains unchanged (frozen), so it doesn’t degrade. However, existing retrieval methods have been clunky. They often require long, complex text prefixes to explain the new fact to the model, or they struggle to decide when to retrieve a fact versus when to rely on the model’s internal memory.

This is where RECIPE enters the picture. It aims to perfect the retrieval-based approach by making the “retrieved” information highly compressed (efficient) and the retrieval mechanism highly intelligent (accurate).

Introducing RECIPE

RECIPE stands for RetriEval-augmented ContInuous Prompt lEarning.

The core philosophy of RECIPE is to treat every piece of new knowledge not as a sentence to be read, but as a “mini-task” to be solved via a learned vector representation. It consists of two primary innovations:

- Knowledgeable Continuous Prompt Learning: Instead of feeding the LLM a long sentence like “The President of the US is Joe Biden,” RECIPE encodes this fact into a short, dense vector (a continuous prompt). This prompt is mathematically optimized to force the LLM to output the correct answer.

- Dynamic Prompt Retrieval with Knowledge Sentinel: A smart gating mechanism that decides whether an incoming user query actually relates to an edited fact. If it does, it retrieves the prompt. If not, it lets the LLM answer normally.

Let’s look at the overall architecture.

As shown in Figure 2, the process is split into three flows:

- Construction (Left): Converting edit examples (e.g., “The CEO of Amazon is Andy Jassy”) into prompts stored in a repository (\(K_t\)).

- Retrieval (Middle): When a query comes in (\(q_1, q_2, q_3\)), the system decides which prompt to pull using the Knowledge Sentinel.

- Inference (Right): The retrieved prompt is tacked onto the front of the query embeddings to guide the frozen LLM (\(f_{llm}\)) to the correct answer.

Component 1: The Continuous Prompt Encoder

The researchers realized that using natural text to edit a model is inefficient. If you prefix every query with “Note: The President is Biden…”, you eat up the model’s context window and slow down processing.

Instead, RECIPE uses Continuous Prompt Learning.

When a new piece of knowledge (\(k_t\)) arrives (e.g., “The CEO of Amazon is Andy Jassy”), it is first processed by a text encoder (like RoBERTa). The output is then passed through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to compress it into a very specific format: a matrix of continuous prompt tokens.

\[r_{k_t} = \mathbf{MLP}_{K}(f_{rm}(k_t))\]\[p_{k_t} = f_{resp}\left(\mathbf{MLP}_{P}\left(r_{k_t}\right)\right)\]Here, \(p_{k_t}\) represents the “Continuous Prompt.” It is a sequence of vectors that mimics the shape of word embeddings but doesn’t necessarily correspond to actual human words. It acts as a “trigger” for the LLM.

The beauty of this is compactness. The researchers found that they could compress a fact into just 3 tokens. Compare this to a natural language instruction which might take 10-20 tokens. This ensures the model remains lightning fast during inference.

Component 2: The Knowledge Sentinel (KS)

The biggest challenge in retrieval-based editing is deciding when to retrieve.

If a user asks, “Who is the CEO of Amazon?”, we want to retrieve the edit. If a user asks, “How do I bake a cake?”, we do not want to retrieve the Amazon fact, nor do we want to feed the model irrelevant noise.

Most systems use a fixed threshold (e.g., “If similarity score > 0.8, retrieve”). The problem is that semantic similarity varies wildly across different topics. A threshold of 0.8 might be too strict for some queries and too loose for others.

RECIPE introduces the Knowledge Sentinel (KS).

The Sentinel is a learnable embedding vector (\(\Theta\)) that acts as a dynamic reference point. It lives in the same vector space as the queries and the knowledge.

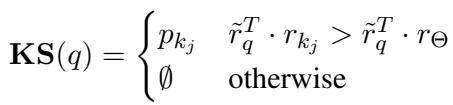

When a query \(q\) comes in, the system calculates two similarity scores:

- Similarity between the query and the most relevant fact in the database (\(r_{k_j}\)).

- Similarity between the query and the Knowledge Sentinel (\(r_{\Theta}\)).

The retrieval logic is elegant in its simplicity:

If the query is closer to the specific fact (\(r_{k_j}\)) than it is to the Sentinel (\(r_{\Theta}\)), it means the system is confident the query is related to that fact. If the query is closer to the generic Sentinel, it implies the query is unrelated to the knowledge base (or “out of scope”), and the system returns an empty set (\(\emptyset\)).

This allows the boundary between “relevant” and “irrelevant” to be learned and dynamic, rather than a hard-coded number.

Component 3: Inference on the Fly

Once a prompt is retrieved (or not), inference is straightforward. The RECIPE framework takes the frozen LLM (denoted as \(\hat{f}_{llm}\) to signify the transformer layers without the embedding layer) and concatenates the prompt vectors with the query vectors.

\[a_q = \hat{f}_{llm}(p_{k_{\tau}} \oplus f_{emb}(q))\]This effectively “prefixes” the hidden instructions to the input. Because the prompt was trained specifically to elicit the target answer, the LLM follows the instruction and outputs the updated fact.

Training the Editor

How does RECIPE learn to generate these magical prompts and train the Sentinel? It uses a joint training process with a frozen LLM. The training data consists of edit examples (Reliability), rephrased queries (Generality), and unrelated queries (Locality).

The loss function is a combination of two objectives:

1. Editing Loss (\(\mathcal{L}_{edit}\))

This ensures the prompt actually works. It forces the model to:

- Reliability: Output the correct answer for the specific edit query.

- Generality: Output the correct answer for rephrased versions of the query (e.g., “Amazon’s boss” instead of “Amazon CEO”).

- Locality: Ensure the prompt doesn’t mess up unrelated questions. It uses Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to ensure the model’s output distribution on unrelated questions stays close to the original, unedited model.

2. Prompt Learning Loss (\(\mathcal{L}_{pl}\))

This uses Contrastive Learning (InfoNCE loss) to train the retriever and the Sentinel.

- Neighbor-oriented Loss: Pulls the representation of the query closer to its corresponding knowledge fact.

- Sentinel-oriented Loss: This is crucial. It pushes unrelated queries away from specific facts and towards the Sentinel. Conversely, it pushes relevant queries away from the Sentinel. \[L_{total} = L_{edit} + L_{pl}\] By minimizing this total loss, RECIPE simultaneously learns how to compress knowledge into prompts and how to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant queries.

Experimental Results

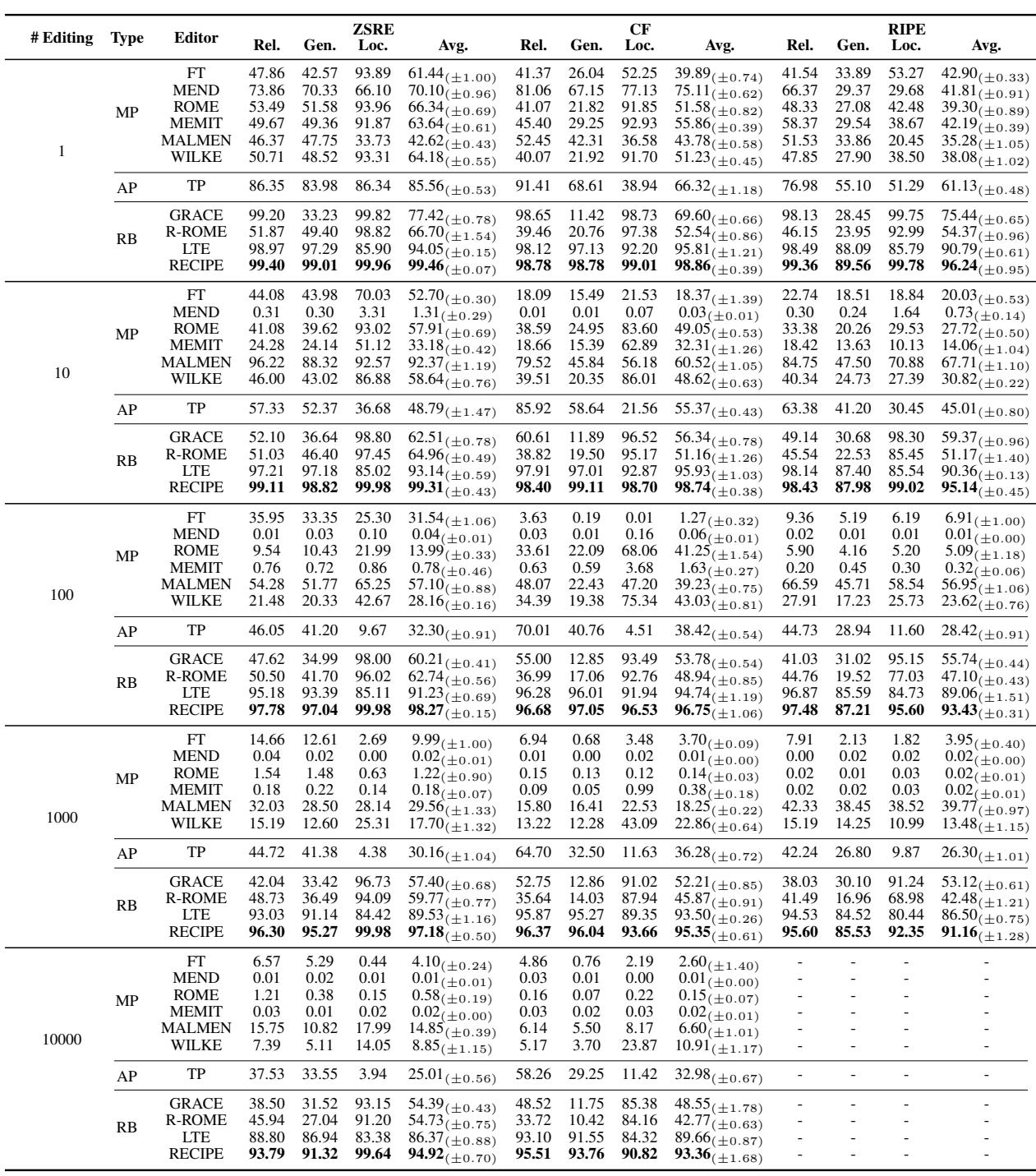

The researchers evaluated RECIPE against a massive suite of baselines, including ROME, MEMIT, MEND, and other retrieval methods like GRACE and LTE. They tested on Llama-2 (7B), GPT-J (6B), and GPT-XL (1.5B) using datasets that simulate lifelong editing (up to 10,000 edits).

1. Lifelong Editing Performance

The results for Lifelong Editing are stark. As the number of edits increases, most methods collapse.

Looking at Table 1 (using Llama-2):

- Modifying Parameters (MP): Methods like ROME and MEMIT start strong at 1 edit but crash significantly by 100 or 1,000 edits. Note the “Rel” (Reliability) scores dropping to near zero for MEMIT at 1,000 edits. This confirms the “toxic accumulation” of weight changes.

- Adding Parameters (AP): T-Patcher (TP) performs decently but struggles with locality (disturbing unrelated facts) as edits grow.

- RECIPE: Consistently maintains near-perfect scores (99%+) across Reliability, Generality, and Locality, even up to 10,000 edits. It outperforms LTE (another retrieval method) and dominates parameter-modification methods.

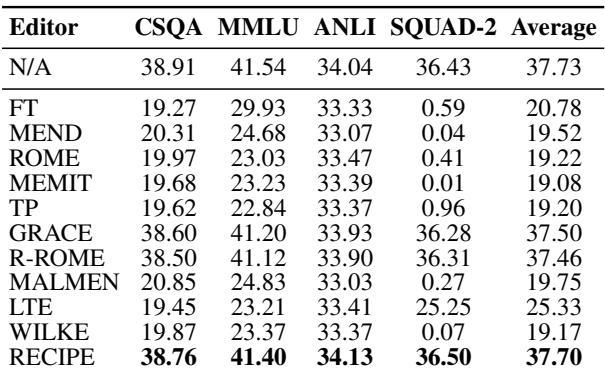

2. General Capabilities

One of the biggest risks of editing an LLM is “lobotomy”—you fix one fact but break the model’s ability to reason or perform standard tasks.

The researchers tested the models on general benchmarks like MMLU (academic subjects) and GSM8K (math) after 1,000 edits.

Table 2 shows that non-retrieval methods (FT, MEND, ROME) cause massive degradation in general performance (Average scores dropping from ~37 to ~19). RECIPE, however, preserves the original model’s performance almost perfectly (Average 37.70 vs. Baseline 37.73). Because RECIPE essentially “guides” the model rather than breaking its internal weights, the model retains its original intelligence.

3. Efficiency

Is it fast? Retrieval systems can be slow if they have to search massive databases or process long contexts.

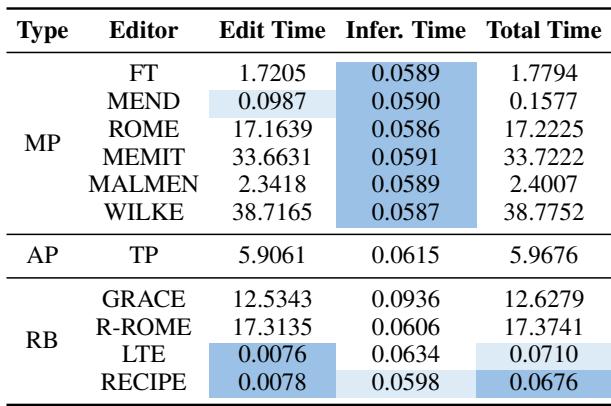

Table 3 highlights the speed.

- Edit Time: RECIPE is nearly instant (0.0078s) to add a new fact because it just involves encoding a string and storing a vector. ROME takes 17 seconds; MEMIT takes 33 seconds.

- Inference Time: Because RECIPE only adds 3 tokens to the input, its inference overhead is negligible compared to the base model. It is faster than LTE and significantly faster than GRACE.

Why 3 Tokens?

One of the interesting ablation studies in the paper asked: “How many tokens do we need to represent a fact?”

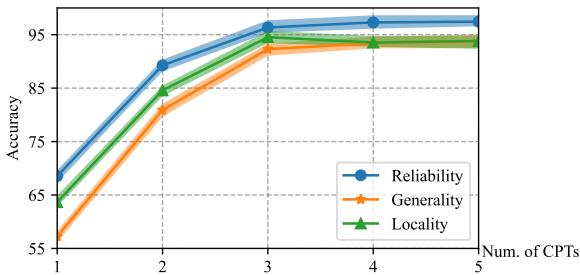

The researchers varied the number of Continuous Prompt Tokens (CPTs) from 1 to 5.

As shown in Figure 3, performance dips with just 1 token (it’s too hard to compress “The President of USA is Biden” into a single vector). However, performance plateaus at 3 tokens.

The authors hypothesize that this aligns with the structure of knowledge triples: (Subject, Relation, Object). For example, (USA, President, Biden).

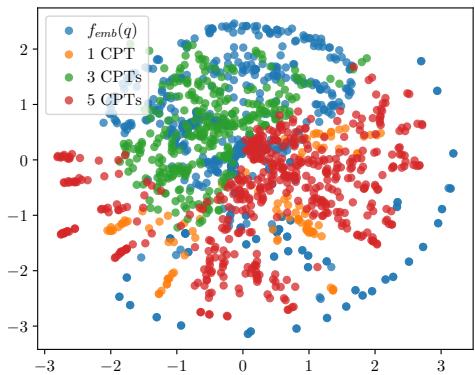

To prove this, they visualized the vector space.

Figure 4 shows a t-SNE visualization. The green dots (3 CPTs) cluster much more closely to the natural word embeddings (red dots) than the 1 CPT or 5 CPT variants. This suggests that 3 tokens is the “sweet spot” for representing factual knowledge in the embedding space of an LLM.

Key Takeaways

The RECIPE paper makes a compelling argument for the future of LLM maintenance. Here is the summary:

- Don’t Modify Weights: For lifelong learning, modifying the model’s weights causes inevitable degradation (catastrophic forgetting).

- Retrieval is King: Keeping the model frozen and retrieving edits is the only way to scale to thousands of updates.

- Continuous Prompts: We don’t need natural language to talk to models. Learned continuous prompts are more efficient and effective for encoding specific facts.

- The Knowledge Sentinel: Dynamic thresholding is essential for accurate retrieval. The Sentinel allows the system to differentiate between “I know this specific edit” and “I should just let the model answer.”

RECIPE offers a path toward LLMs that can be updated continuously, instantly, and indefinitely, without ever needing a full retraining run. For anyone building AI systems that need to stay current with the world, this is a methodology worth watching.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.03279/images/cover.png)