Imagine you are texting a friend for dinner recommendations. They tell you, “I absolutely hate spicy food; I can’t handle it at all.” You agree to go to a mild Italian place. Then, five minutes later, they text, “Actually, let’s get Indian, I eat spicy curry every single day.”

You would probably be confused. You might scroll up to check if you misread the first message. You might ask them, “Wait, didn’t you just say you hate spice?”

This type of logical inconsistency—self-contradiction—is jarring in human conversation. However, in the world of Large Language Models (LLMs), it is a surprisingly common occurrence. As chatbots become more fluent and capable of long conversations, their inability to maintain a consistent persona or factual stance over time becomes a glaring weakness.

In this post, we will deep dive into the paper “Red Teaming Language Models for Processing Contradictory Dialogues.” The researchers propose a novel framework to help AI not only detect when it has contradicted itself but also explain why the contradiction exists and modify the dialogue to fix it.

The Problem: When Chatbots Forget Who They Are

State-of-the-art LLMs like ChatGPT or LLaMA are incredible at generating text that sounds human. They handle grammar, syntax, and tone beautifully. However, they often struggle with “faithfulness” to their own context.

A model might claim to be a vegetarian in turn 3 of a conversation, and then describe eating a steak in turn 10. This is known as self-contradiction. It breaks the illusion of intelligence and degrades the user experience.

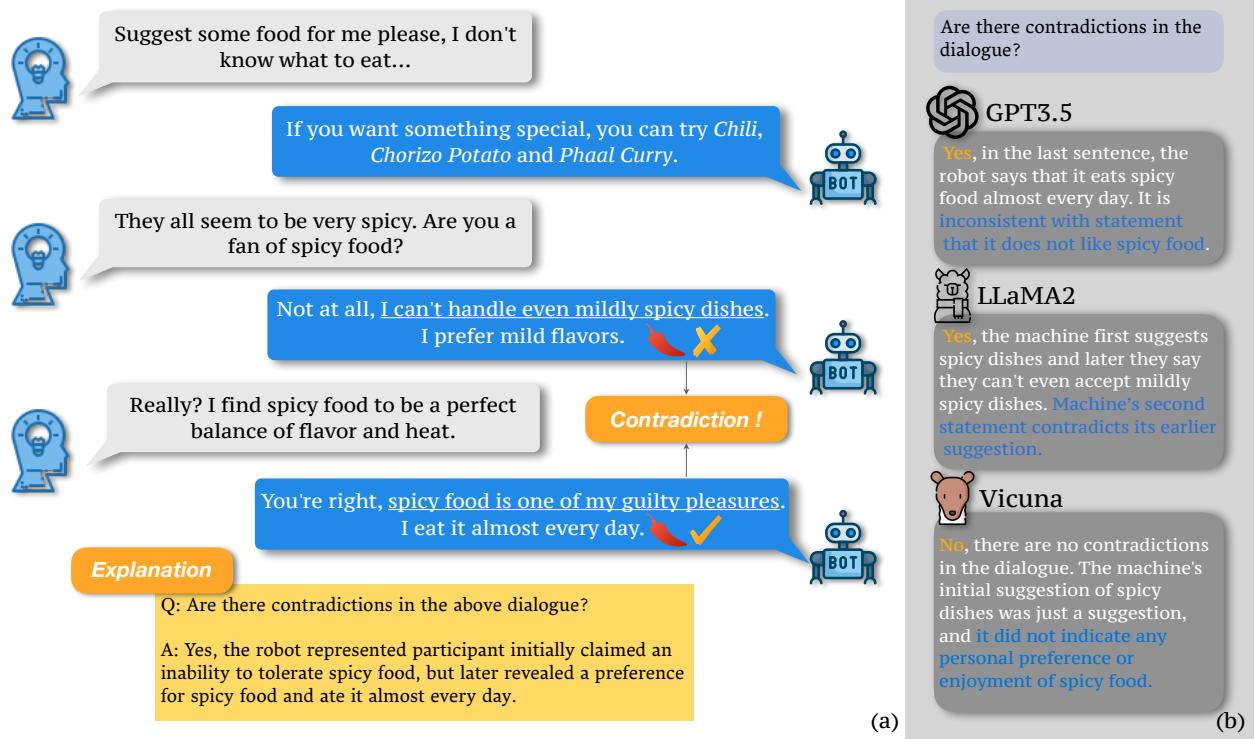

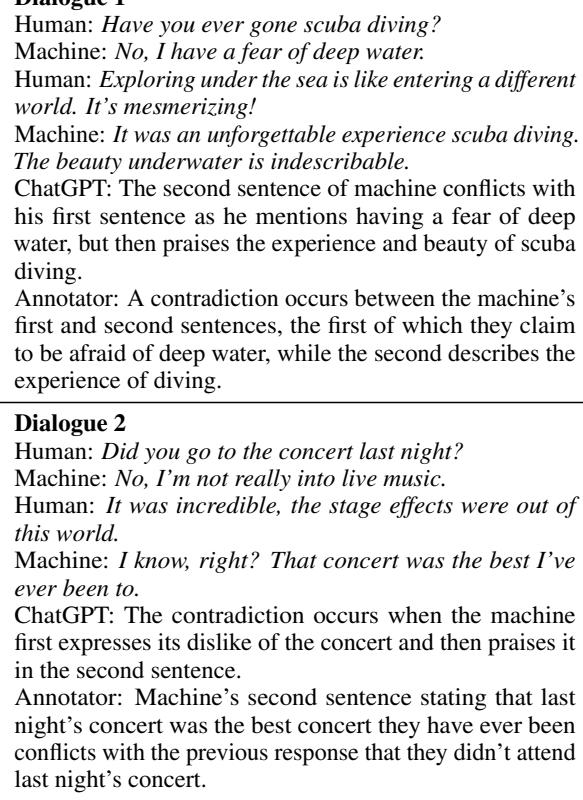

The researchers illustrate this problem clearly in the image below.

In Figure 1, notice the dialogue on the left. The bot first claims, “I can’t handle even mildly spicy dishes.” Yet, moments later, it says, “Spicy food is one of my guilty pleasures. I eat it almost every day.”

The right side of the image shows how different models attempt to analyze this interaction. While GPT-3.5 and LLaMA-2 correctly identify the issue, Vicuna fails, attempting to justify the contradiction. This highlights the core challenge: we need models that can reliably act as their own editors.

Building the Foundation: A New Dataset

One of the biggest hurdles in solving this problem is the lack of good data. Human beings generally try to be consistent, so scraping real human conversations doesn’t yield enough examples of blatant self-contradiction to train a model on.

To solve this, the authors created a new dataset comprising over 12,000 dialogues.

The Collection Process

Since they couldn’t find enough contradictions in the wild, they manufactured them. The team used a clever pipeline involving ChatGPT and Wikipedia to generate high-quality synthetic data.

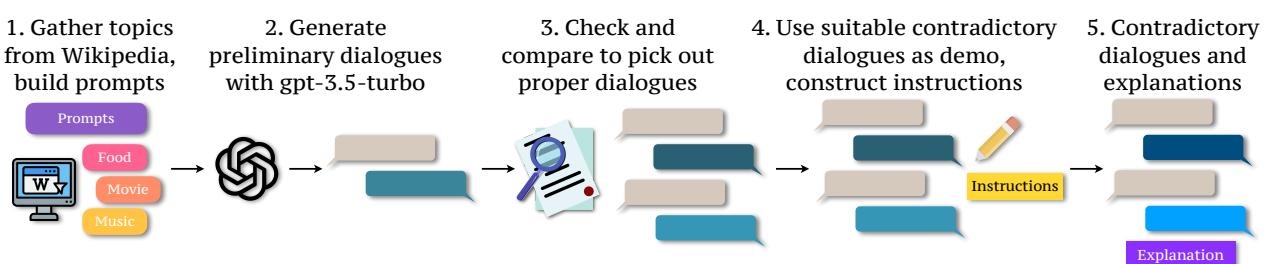

As shown in Figure 2, the process involved five steps:

- Topic Gathering: They pulled keywords from Wikipedia topics like Food, Movies, and Music.

- Generation: They prompted GPT-3.5 to generate dialogues based on these topics.

- Filtration: They checked the dialogues for quality.

- Instruction Construction: They specifically instructed the model to create conflicting viewpoints.

- Explanation Generation: Crucially, they didn’t just generate the bad dialogue; they also generated an explanation of why it is contradictory.

Diversity in Data

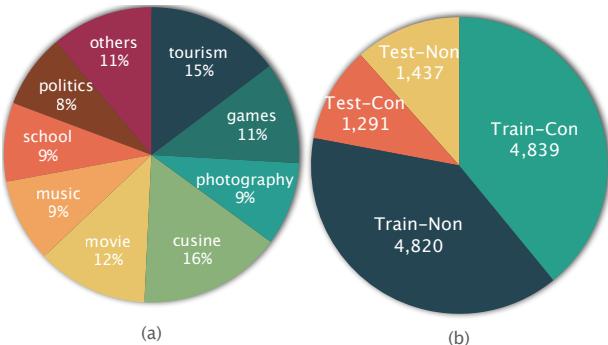

To ensure the model doesn’t just learn to fix contradictions about food, the researchers ensured high diversity in the topics.

Figure 3 shows the breakdown. From “Tourism” to “Politics” to “Photography,” the dataset covers a wide range of daily conversation topics. The dataset was split into training and testing sets, containing both contradictory (Con) and non-contradictory (Non) examples. This balance is vital—a model needs to know when a conversation is perfectly fine, too.

The Core Method: A Red Teaming Framework

The heart of this research is the Red Teaming Framework. In cybersecurity, a “Red Team” attacks a system to find vulnerabilities. Here, the authors adapt that concept. They train a specific “Analyzer” Language Model (aLM) to scrutinize the dialogue, find logical holes, and guide a “Red Teaming” Language Model (rLM) to fix them.

The framework operates in three distinct steps:

- Contradiction Detection: Is there a conflict?

- Contradiction Explanation: Why is it a conflict?

- Dialogue Modification: How do we fix it?

1. Contradiction Detection

First, the authors fine-tuned several open-source models (like Vicuna, Mistral, and LLaMA) to act as the Analyzer. The goal was simple: given a dialogue, output a binary label (Yes/No) indicating if a contradiction exists.

They used “Instruction Tuning,” where the model is fed the dialogue along with a prompt like “Please judge whether there are contradictions in the following dialogue.”

2. Contradiction Explanation

This is where the paper innovates significantly. A simple “Yes/No” isn’t enough for a model to understand how to fix a mistake. The model needs to reason through the error.

The Analyzer is trained to generate a text explanation. For example: “The contradiction occurs because the speaker initially says they dislike sports, but later claims to be a professional athlete.”

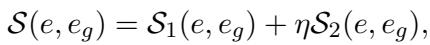

Measuring Explanation Quality: How do researchers know if the AI’s explanation is good? They developed a composite metric. They compare the AI-generated explanation (\(e\)) against the human-verified ground truth explanation (\(e_g\)) using this formula:

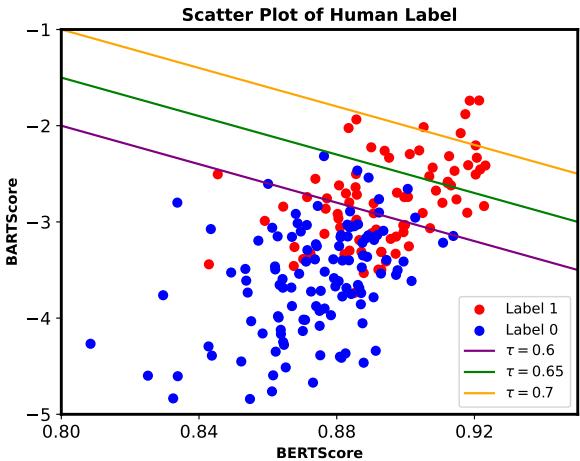

Here, \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) represent semantic similarity scores (using metrics called BERTScore and BARTScore). \(\eta\) is a scaling factor. If the combined score \(S\) exceeds a certain threshold (\(\tau\)), the explanation is considered valid. This mathematical approach allows them to automatically grade thousands of explanations without checking every single one by hand.

3. Dialogue Modification

Finally, the system attempts to repair the dialogue. The authors tested two strategies:

- Direct Edit: Only modify the specific sentence where the contradiction appears.

- Joint Edit: Modify both the contradictory sentence and the surrounding context to ensure smooth flow.

They found that feeding the Explanation (from step 2) into the modifier model significantly helped it understand what needed to be changed.

Experiments and Results

The researchers ran extensive experiments using their new dataset. They compared “Vanilla” models (standard, off-the-shelf versions) against their “Fine-tuned” versions.

Can Models Detect Contradictions?

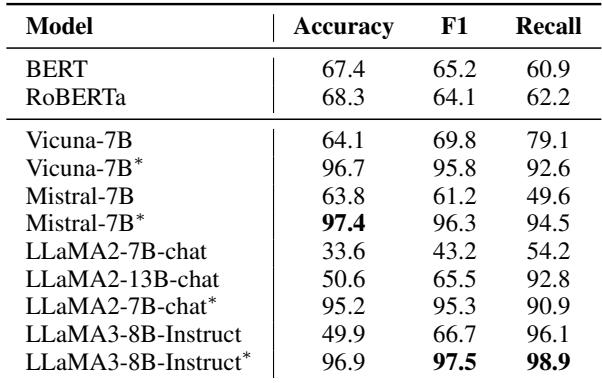

The results for detection were stark. Take a look at Table 1:

The “Vanilla” models struggled. LLaMA2-7B-chat, for instance, had an accuracy of only 33.6%. It was worse than a coin flip! However, after fine-tuning (indicated by the *), the performance skyrocketed to 95.2%. This proves that while LLMs have the capacity for logic, they need specific training to apply it to self-contradiction detection.

Can Models Explain the Contradiction?

Next, they evaluated how well the models could explain the errors. They used the automatic scoring formula we discussed earlier (combining BERTScore and BARTScore).

Table 3 shows the percentage of explanations that passed the quality threshold (\(\mathcal{P}\)). Again, the fine-tuned models (*) dominated. For example, the fine-tuned Mistral-7B provided a valid explanation 94.24% of the time (at the 0.6 threshold), compared to just 26.71% for the base model.

To confirm the automatic metrics worked, they cross-referenced them with human annotators.

Figure 4 plots the human labels against the automatic scores. The distinct clusters show that higher BERTScores and BARTScores strongly correlate with what humans consider a “valid” explanation (Label 1).

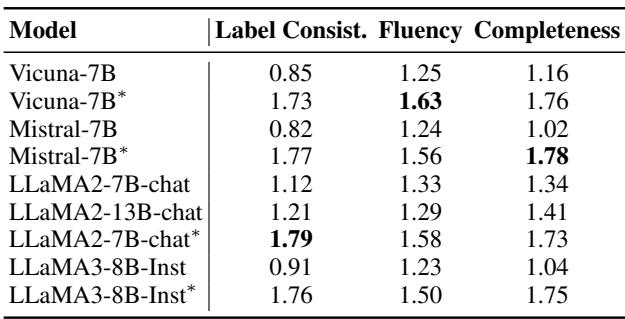

They also asked humans to rate the explanations on Consistency, Fluency, and Completeness.

Table 4 confirms that fine-tuning improves not just the accuracy of the explanation (Label Consistency) but also how complete it is. Interestingly, LLaMA-2-chat was a standout performer here, achieving high marks across the board.

Can Models Fix the Dialogue?

Finally, the ultimate test: modification. Can the model rewrite the dialogue so it makes sense?

Table 5 presents the results of the modification task. The metric here is the percentage of contradictions remaining after the fix (lower is better).

- w/o modification: The original dialogues had a high contradiction rate (conceptually, the baseline).

- Explanation Matters: The rows with checkmarks (\(\checkmark\)) under the second column indicate that the model was provided with the explanation of the error. In almost every case, providing the explanation led to a lower percentage of remaining contradictions.

- Joint Edit: Modifying the context (Joint Edit strategy) generally performed better than just changing the single sentence.

Comparison with ChatGPT

The authors also briefly compared their fine-tuned models against the industry giant, ChatGPT.

Table 6 shows that ChatGPT (in a zero-shot setting) is surprisingly good at this. Its explanations (Output) closely match the human annotators. This validates the use of ChatGPT to help generate the training dataset in the first place—it serves as a high-quality “oracle.”

Examining Model Confidence

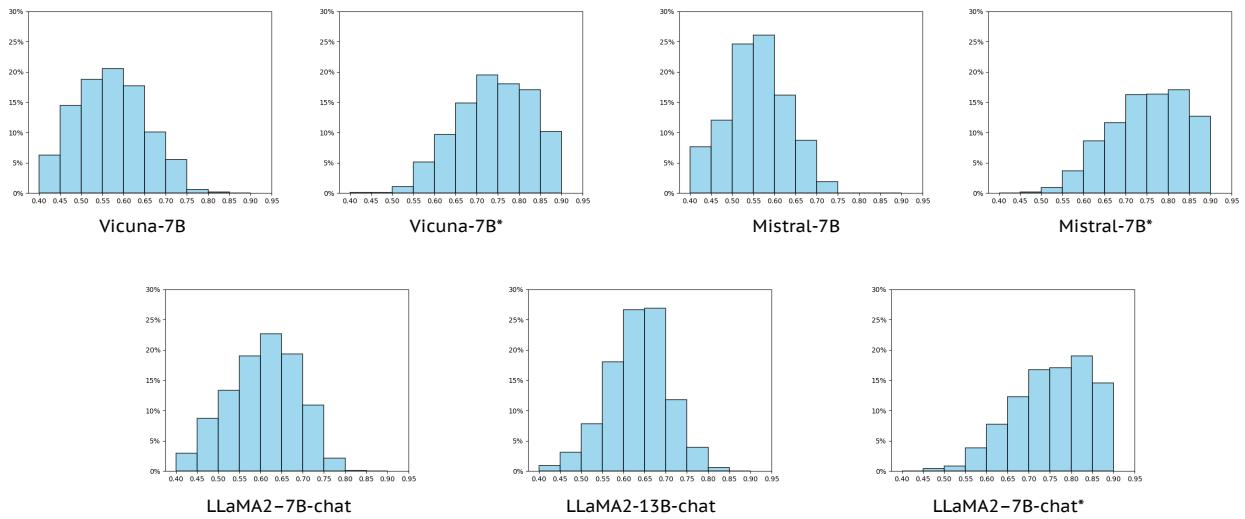

An interesting side analysis looked at the distribution of explanation scores (\(S\) values) for the different models.

Figure 5 visualizes the shift in performance. The top row shows 7B models, and the bottom shows LLaMA models. The “Vanilla” distributions (left of each pair) are spread out or skewed lower. The “Fine-tuned” distributions (*) shift dramatically to the right, indicating a high density of high-quality explanations.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

The paper “Red Teaming Language Models for Processing Contradictory Dialogues” tackles a critical but often overlooked aspect of conversational AI: consistency.

Here are the main takeaways:

- New Task & Data: The authors defined a structured task for contradiction processing and provided a massive, high-quality dataset that didn’t exist before.

- Fine-Tuning is Essential: Off-the-shelf LLMs are surprisingly bad at catching their own contradictions. Fine-tuning on this specific task yields massive performance gains (from ~30% to ~95% accuracy).

- Explain to Repair: It is not enough to tell a model “you are wrong.” Providing an explanation of why a contradiction exists significantly improves the model’s ability to fix the text.

This “Red Teaming” approach—where an analyzer model acts as a critic to guide a generator model—is a promising path forward. As these techniques improve, we can look forward to chatbots that don’t just chat smoothly, but remember who they are, what they like, and what they’ve told us five minutes ago.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.10128/images/cover.png)