Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized how we interact with information. We ask them to write code, solve math problems, and explain complex historical events. However, anyone who has used these models extensively knows they have a significant weakness: hallucination. They can sound incredibly confident while stating completely incorrect facts.

In recent years, researchers have developed clever ways to mitigate this. One popular method is “consistency checking”—asking the model the same question multiple times and picking the answer that appears most often. This works wonders for math problems where the answer is a single number. But what happens when you ask a long-form question like, “What are the main causes of climate change?”

The answer isn’t a single number; it’s a paragraph containing multiple distinct facts. If you generate ten different paragraphs, none of them will be identical word-for-word. How do you check for consistency then?

In this post, we will dive into a fascinating paper titled “Atomic Self-Consistency for Better Long Form Generations.” The researchers propose a novel method called Atomic Self-Consistency (ASC). Instead of trying to pick the single “best” generated response, ASC breaks multiple responses down into their “atomic” parts (facts), identifies which facts appear consistently across samples, and stitches them together into a new, superior answer.

The Problem: Precision vs. Recall in Long-Form QA

When an LLM generates a long answer, two things define its quality:

- Precision: Is the information provided actually true? (avoiding hallucinations).

- Recall: Did the model include all the relevant information?

Current methods for fixing hallucinations often focus heavily on precision. They might filter out anything that looks suspicious, leaving you with a very short, safe answer. However, a good answer needs to be comprehensive.

Consider the example below from the paper.

In Figure 1, Answer \(A_1\) is precise—it lists human activities. But Answer \(A_2\) is much better because it has higher recall; it includes both human activities and natural factors.

Existing state-of-the-art methods, such as Universal Self-Consistency (USC), operate by generating multiple responses and trying to select the single most consistent one. The flaw here is obvious: what if the “best” response misses a key fact that was present in the “second-best” response? By picking only one winner, we leave valuable information on the table.

The Motivation: Why Merging is Better Than Selecting

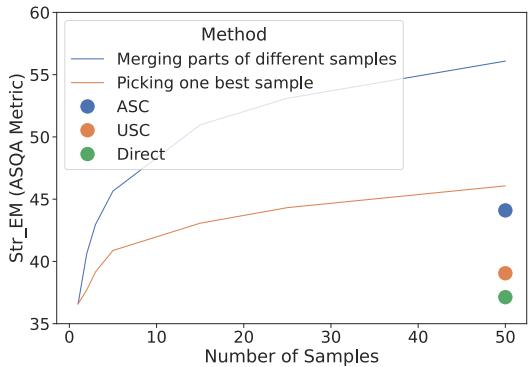

The core hypothesis of this research is that merging parts of different answers is superior to selecting just one.

To prove this potential before building their method, the researchers analyzed the “Oracle” performance (the theoretical best performance possible) on the ASQA dataset. They compared the ceiling of picking the best single sample versus merging subparts of multiple samples.

As shown in Figure 2, the blue dashed line (“Merging parts”) creates a much higher performance ceiling than the orange line (“Picking one best sample”). The gap between these lines represents the untapped potential of combining knowledge.

This insight drives the development of Atomic Self-Consistency (ASC). The goal is to create a system that doesn’t just judge answers, but actively synthesizes them.

The Core Method: Atomic Self-Consistency (ASC)

So, how does ASC actually work? The process is inspired by the idea that if an LLM mentions a specific fact (an “atom”) across multiple independent generations, that fact is likely true. If a fact only appears once in 50 generations, it is likely a hallucination.

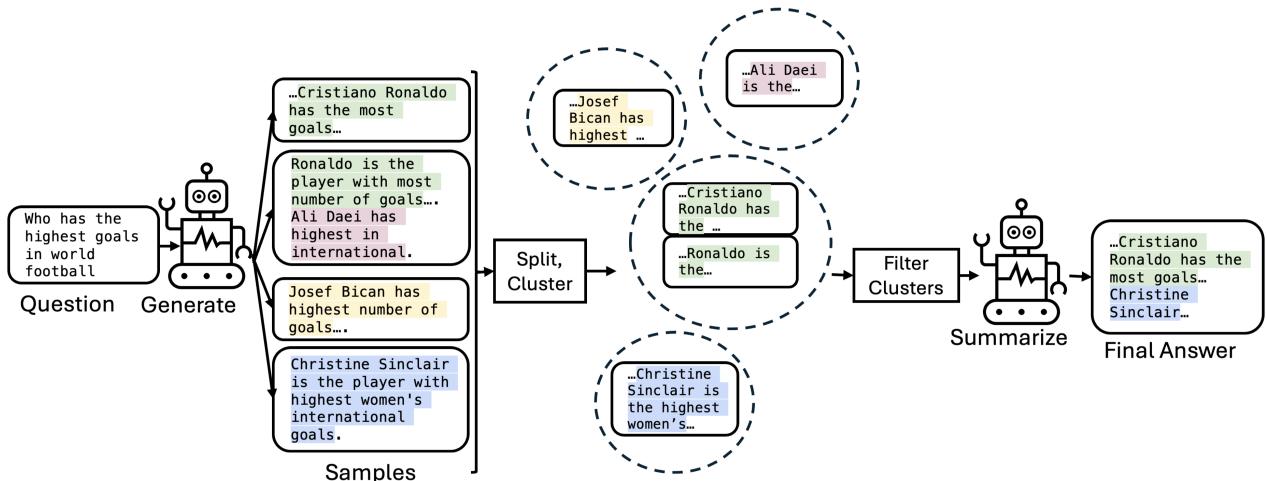

The ASC pipeline operates in four distinct steps: Split, Cluster, Filter, and Summarize.

Let’s break down the pipeline illustrated in Figure 3:

Step 1: Generation & Splitting (The Atoms)

First, the system prompts the LLM to answer a question multiple times (e.g., \(m=50\) samples). Instead of treating these 50 paragraphs as monolithic blocks, ASC splits them into their constituent parts. In this paper, the researchers treat individual sentences as “atomic facts.”

- Input: “Who has the highest goals in world football?”

- Generations: 50 different paragraphs about Ronaldo, Bican, Sinclair, etc.

- Split: The system breaks these down into hundreds of individual sentences.

Step 2: Clustering

Now the system has a bag of hundreds of sentences. Many of these sentences say the same thing but in different words (e.g., “Ronaldo has the most goals” vs. “Cristiano Ronaldo is the top scorer”). ASC uses a clustering algorithm (specifically agglomerative clustering using sentence embeddings) to group these semantically similar sentences together.

- Result: A cluster of “Ronaldo” facts, a cluster of “Sinclair” facts, and perhaps a small cluster of hallucinated facts about a random player.

Step 3: Filtering (The Consistency Check)

This is the magic step. The researchers use cluster consistency as a proxy for correctness.

- If a cluster is large (contains many sentences from different samples), it has high consistency strength. The model is confident about this fact.

- If a cluster is tiny (contains few sentences), it has low strength. This is likely a hallucination or irrelevant noise.

The system applies a threshold (\(\Theta\)). Any cluster with a size below this threshold is discarded. The longest sentence in each surviving cluster is kept as the “representative.”

Step 4: Summarization

Finally, we have a list of verified, high-consistency facts (representatives). But a list of disconnected sentences isn’t a good blog post or answer. ASC feeds these selected sentences back into the LLM with a prompt asking it to summarize them into a coherent answer. This creates a final response that combines the best parts of all 50 original generations while filtering out the noise.

Experimental Results

Does this complex merging process actually beat simply asking the LLM to “pick the best one”? The researchers tested ASC across four diverse datasets:

- ASQA: Factoid questions with long, ambiguous answers.

- QAMPARI: List-style questions (e.g., “List the movies directed by…”).

- QUEST: Another difficult list-style dataset.

- ELI5: “Explain Like I’m 5” (open-ended explanations).

They compared ASC against:

- Direct: The standard output of the LLM.

- USC (Universal Self-Consistency): Selecting the single most consistent full response.

- ASC-F: A variation of their method using retrieval-based fact-checking instead of self-consistency.

Performance Analysis

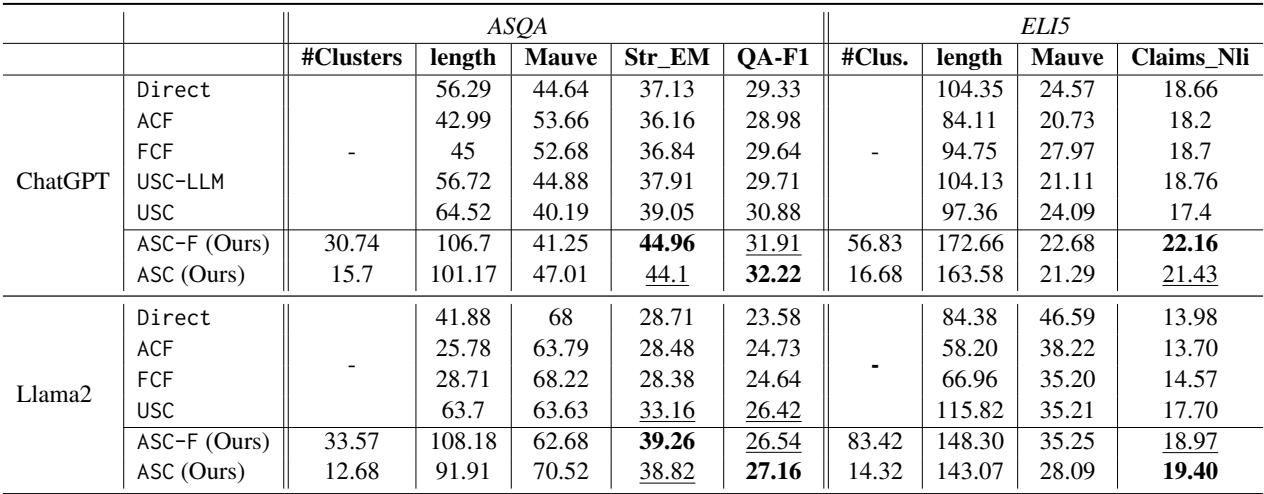

Table 1 highlights the results on ASQA and ELI5. Here is what the metrics tell us:

- Str_EM (Exact Match): ASC scores significantly higher than Direct and USC. This indicates better recall of specific reference answers.

- QA-F1: This measures how well the answer allows a QA model to retrieve correct information. Again, ASC outperforms the baselines.

- Mauve: This measures how human-like and fluent the text is. ASC achieves a high Mauve score, indicating that stitching sentences together didn’t result in a “Frankenstein” monster of text; the summarization step smoothed it out effectively.

The results confirm that merging subparts of multiple samples performs significantly better than picking a single sample.

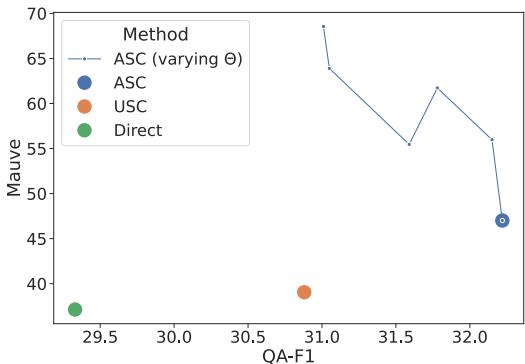

Sensitivity: The Power of Tuning \(\Theta\)

One of the strongest features of ASC is its flexibility. The threshold \(\Theta\) (how big a cluster needs to be to survive) acts as a control knob for the output style.

- Low \(\Theta\): You let more clusters in. This increases Recall (you get more facts) but might lower Precision (some wrong facts might slip in). It also makes the answer longer.

- High \(\Theta\): You are very strict. Only the most repeated facts survive. This increases Precision and Fluency (Mauve score) but might miss minor details.

Figure 4 illustrates this trade-off on the ASQA dataset. As you adjust the threshold, you can optimize for either a highly fluent, precise answer (High Mauve) or a highly detailed, comprehensive answer (High QA-F1). This level of control isn’t possible with standard prompting or simple selection methods.

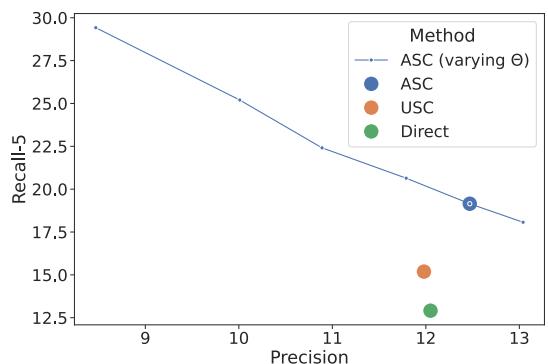

The same trend appears in list-style datasets like QAMPARI, as seen below in Figure 6. Increasing the threshold drastically improves precision (making sure every item on the list is correct) at the cost of recall (the list might be shorter).

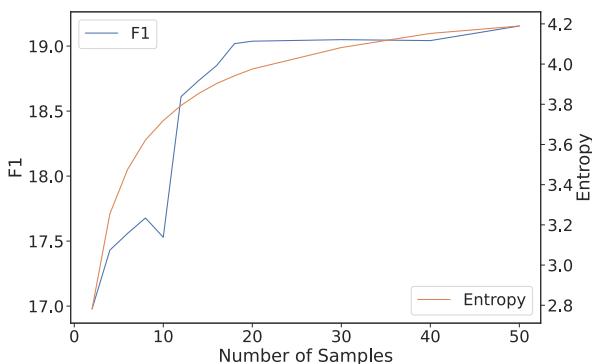

Efficiency: Do We Really Need 50 Samples?

Generating 50 full responses from an LLM is computationally expensive and slow. A key question the researchers asked was: Can we stop earlier?

They analyzed the entropy of the clusters. Entropy is a measure of disorder or unpredictability. When you generate the first few samples, new clusters are forming constantly, and entropy rises. However, after a certain number of samples, the “facts” start repeating. The clusters just get bigger, but new clusters stop appearing.

Figure 5 reveals an important correlation. The blue line (F1 Score) starts to plateau at roughly the same time the orange line (Entropy) stabilizes. This suggests a practical optimization: systems can monitor the entropy of the clusters in real-time and stop generating new samples once the entropy flattens out. This could save massive amounts of compute while retaining most of ASC’s benefits.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The paper “Atomic Self-Consistency for Better Long Form Generations” marks a shift in how we think about improving LLM reliability. It moves us away from the idea of “generating the perfect answer” and toward “synthesizing the truth from multiple attempts.”

Key Takeaways:

- Don’t Settle for One: Merging relevant parts of multiple generated samples yields better results than trying to find the single best sample.

- Consistency is Key: If an LLM says the same thing in 10 different ways, it’s likely true. Measuring this consistency at the “atomic” (sentence) level is more granular and effective than at the document level.

- Control: The method offers a tunable parameter (\(\Theta\)) to balance the trade-off between being comprehensive (high recall) and being safe/fluent (high precision).

Perhaps most exciting is the “Oracle” analysis shown earlier. While ASC is a significant improvement over current methods, it still hasn’t hit the theoretical ceiling of what is possible by merging samples. There is still “untapped potential” in the data LLMs generate. Future work that combines ASC with external verification (like checking facts against Google Search) could push LLM reliability even further.

For students and practitioners, ASC demonstrates that we can treat LLMs not just as writers, but as sources of raw data that—with the right algorithm—can be mined for the truth.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.13131/images/cover.png)