Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4, LLaMA, and Mistral have revolutionized natural language processing. If you speak English, these tools feel almost magical. However, if you switch to a low-resource language—say, Swahili or Bengali—the “magic” often fades. The performance gap between high-resource languages (like English and Chinese) and low-resource languages remains a massive hurdle in AI equity.

Traditionally, fixing this required massive amounts of multilingual training data or complex translation pipelines. But what if LLMs already know how to handle these languages, and we just aren’t asking them correctly?

In the paper “Getting More from Less: Large Language Models are Good Spontaneous Multilingual Learners,” researchers from Nanjing University and China Mobile Research uncover a fascinating phenomenon. They discovered that by training an LLM on a simple translation task using only questions (without answers) in a few languages, the model “spontaneously” improves its performance across a wide range of other languages—even those it wasn’t explicitly tuned for.

This post will walk you through their methodology, the “question alignment” paradigm, and the mechanistic interpretability that explains how models “think” across languages.

The Problem: The Multilingual Gap

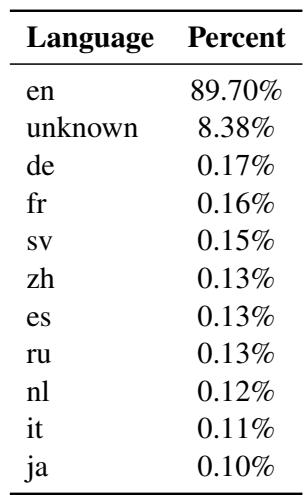

Most open-source LLMs are “English-centric.” As shown in the training data distribution for LLaMA 2 below, English dominates the corpus (nearly 90%), while other languages comprise mere fractions of a percent.

Because of this imbalance, LLMs struggle with tasks in low-resource languages. The standard solution has been Instruction Tuning, where models are fine-tuned on datasets containing prompts and answers in various languages. However, creating high-quality, human-annotated datasets for every language is expensive and slow.

Another approach is the Translate-Test method: translate a user’s prompt into English, let the LLM solve it, and translate the answer back. While effective, this is cumbersome and relies heavily on external translation systems.

The researchers propose a third way: Question Alignment. They hypothesize that LLMs acquire multilingual capabilities during pre-training, but these capabilities are dormant. They just need a light “nudge” to be aligned.

The Core Method: Question Alignment

The core contribution of this paper is a method that improves multilingual performance without needing annotated answers for downstream tasks. This is crucial because it suggests we don’t need expensive “QA pairs” (Question-Answer) to teach the model. We only need the questions.

The Pipeline

The process is surprisingly elegant. The researchers take a specific task (like Emotion Classification) and strip away the answers, leaving only the input questions. They then create a parallel dataset where these questions are translated from a source language to a target language (usually English).

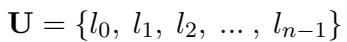

Let’s break down the formal definition. First, we define a universal set of languages:

Here, \(l_0\) typically represents English. The researchers select a small subset of source languages (e.g., Chinese and German) and a target language (e.g., English). They construct a dataset of parallel questions \((q_s, q_t)\), where \(q_s\) is the question in the source language and \(q_t\) is the translation in the target language.

Crucially, the model is NOT trained to solve the task (e.g., classify emotion). It is only trained to translate the question.

The training objective is to minimize the loss on this translation task:

This equation represents standard instruction tuning (using LoRA, or Low-Rank Adaptation) where the model parameters \(\theta\) are updated to maximize the probability of generating the translated question \(q_t\) given the input \(q_s\).

After this training phase, we get a new set of parameters:

Testing the “Spontaneous” Improvement

Once the model is tuned on this simple translation task, the researchers test it on the actual downstream tasks (like Sentiment Analysis) across all languages in the universal set—including languages the model saw no translation data for.

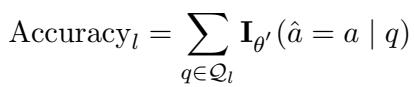

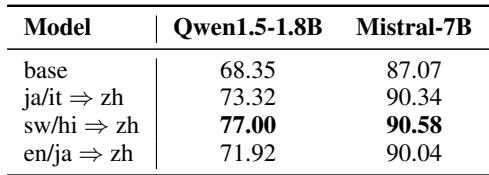

They measure success using Accuracy. For a specific language \(l\), accuracy is defined as:

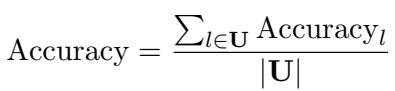

And the global accuracy is the average across all tested languages:

The hypothesis is that by forcing the model to align questions from Language A to English, it learns a generalizable alignment skill that “unlocks” its ability to handle Language B, C, and D, even if it never saw translation data for them during this tuning phase.

Experiments and Key Results

The researchers tested this method on two major model families: Mistral (7B), which is English-centric, and Qwen1.5 (1.8B to 14B), which has stronger multilingual baselines. They used three distinct tasks:

- Emotion Classification: (Amazon Reviews Polarity)

- Natural Language Inference (NLI): (SNLI)

- Paraphrase Identification: (PAWS)

Result 1: Significant Improvement on Unseen Languages

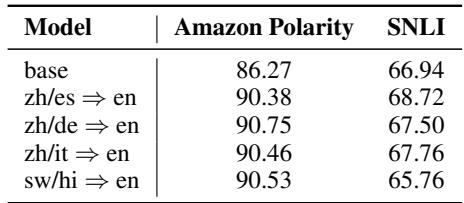

The results on the Mistral-7B model are striking. In the table below, the “Base” row shows the original model’s performance. The subsequent rows show performance after being tuned on specific language translation pairs (e.g., zh => en means Chinese to English).

What to look for in this table:

- Broad Generalization: Look at the column for Swahili (

sw) or Hindi (hi). The base model struggles (e.g., 58.0% onsw). However, when the model is trained on Chinese-to-English translation (zh => en), the performance on Swahili jumps to 75.8%. The model never saw Swahili during tuning, yet it improved significantly. - High-Resource Leaders: Training on high-resource languages (like Chinese, German, or Spanish) often yields better results across the board than training on low-resource languages.

- Efficiency: You don’t need to train on all languages. Training on a mix of just 2 or 3 languages (e.g.,

zh/es => en) provides massive gains across all 20 tested languages.

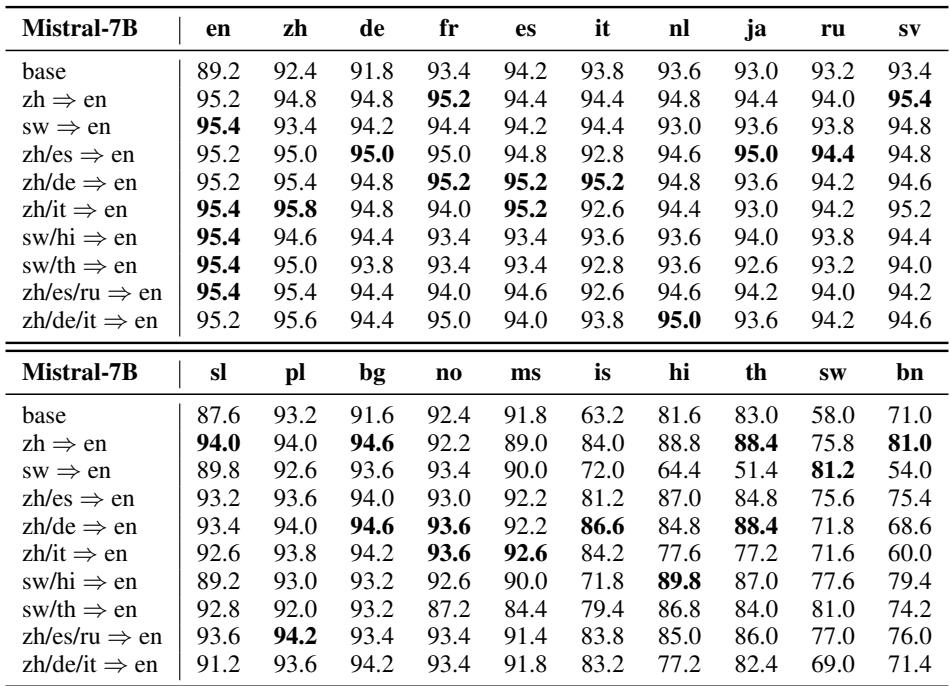

Result 2: Scaling Across Model Sizes

To ensure this wasn’t a fluke specific to Mistral, they tested the Qwen1.5 family at different parameter counts (1.8B, 4B, and 14B).

As shown above, the improvement is consistent. Even smaller models (1.8B) see a jump in performance (from 68.35% to 76.13%) when aligned with Chinese/Spanish to English data. This proves the method is robust across model architectures and sizes.

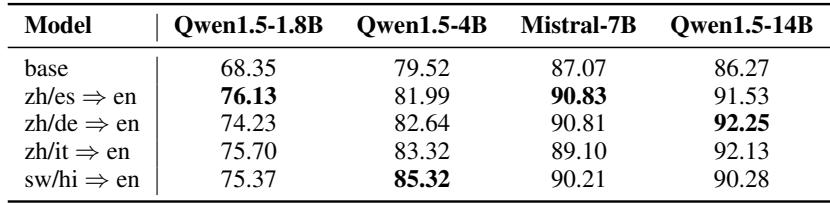

Result 3: English is Not the Only Destination

A common critique in multilingual NLP is that everything relies on English as the “pivot” language. The researchers asked: Does the target language have to be English?

They repeated the experiments using Chinese as the target language for translation (e.g., translating Japanese to Chinese).

The result? It works just as well. Whether targeting English or Chinese, the alignment process enhances the model’s general multilingual reasoning. This suggests the improvement comes from the process of alignment itself, not just from mapping everything to English.

Result 4: Data Distribution Matters

The researchers also investigated whether the type of data matters. If we want the model to be good at Sentiment Analysis, should we train it on translating Sentiment Analysis questions?

The answer is yes. Table 5 shows that while any translation training helps, training on data that shares the same distribution as the test task (e.g., training on Amazon Polarity questions to test on Amazon Polarity) yields the best results. This aligns with the “Superficial Alignment Hypothesis”—the idea that the model creates a “sub-distribution of formats” during alignment that it can leverage during inference.

Peeking Inside the “Black Box”

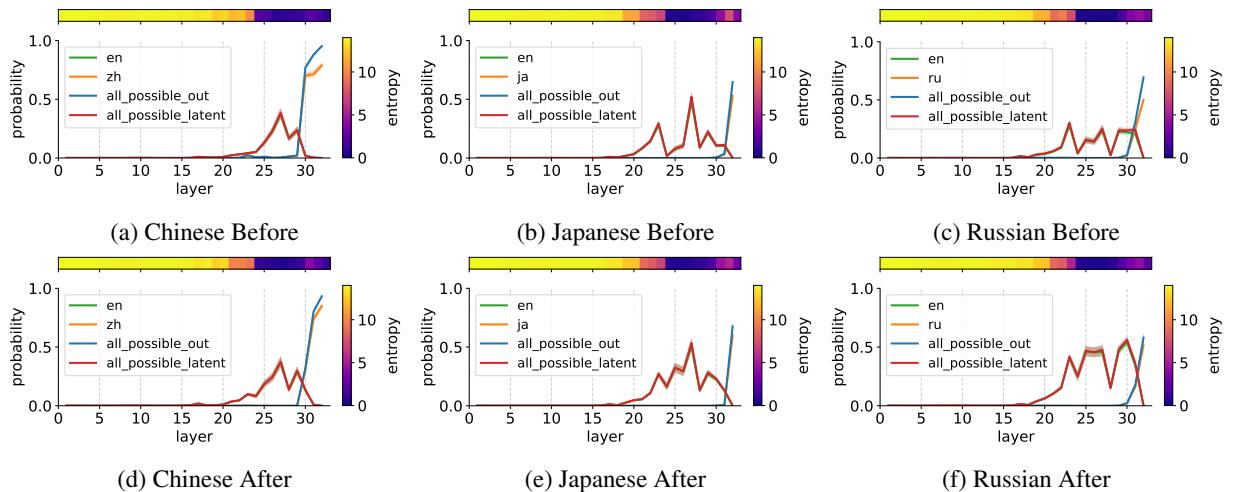

Why does this work? The researchers employed Mechanistic Interpretability techniques to visualize what happens inside the model’s neural network layers.

The “Logit Lens”

The “Logit Lens” is a technique where we take the internal state of the model at a middle layer and project it onto the vocabulary to see what word the model would predict if it stopped right there.

The researchers discovered that LLMs often “think” in English. When given a prompt in a non-English language, the model translates it to an abstract English representation in its middle layers before translating it back to the target language for the final output.

Analyzing Figure 1:

- Top Row (Before Training): In the base model, the probability of the correct answer (in orange) is low and unstable.

- Bottom Row (After Training): After training on translation data, look at the Red Area. This represents the “Latent English Output.” The model builds a strong probability for the English version of the answer in the middle layers (around layer 20-30).

- The Conclusion: The training process strengthens this internal “English pivot” mechanism. The model becomes more confident in mapping the input language to its internal English representation, performing the reasoning, and then generating the correct output.

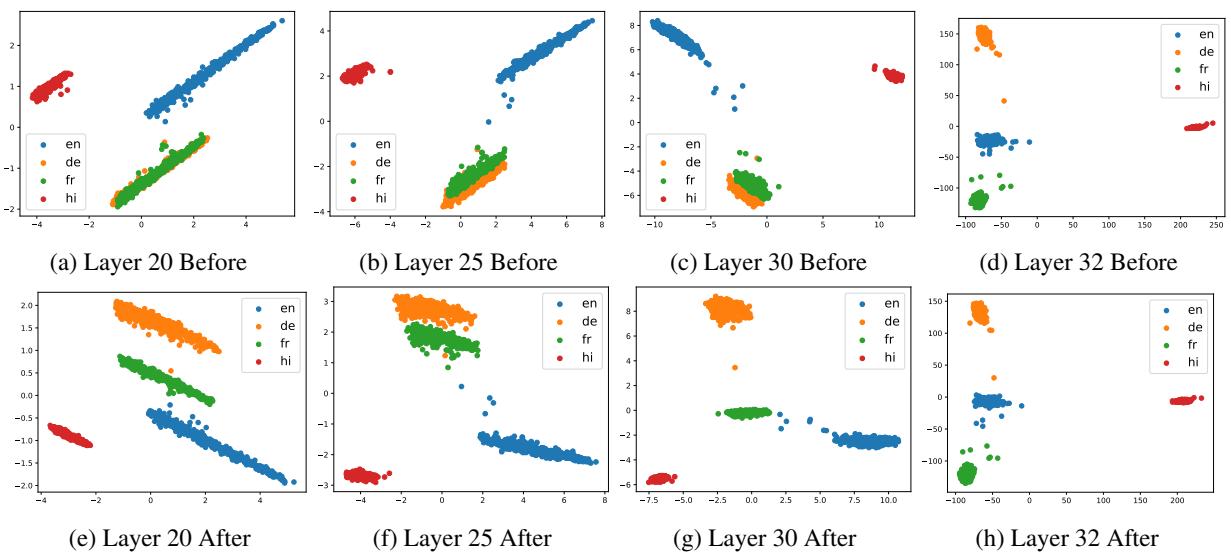

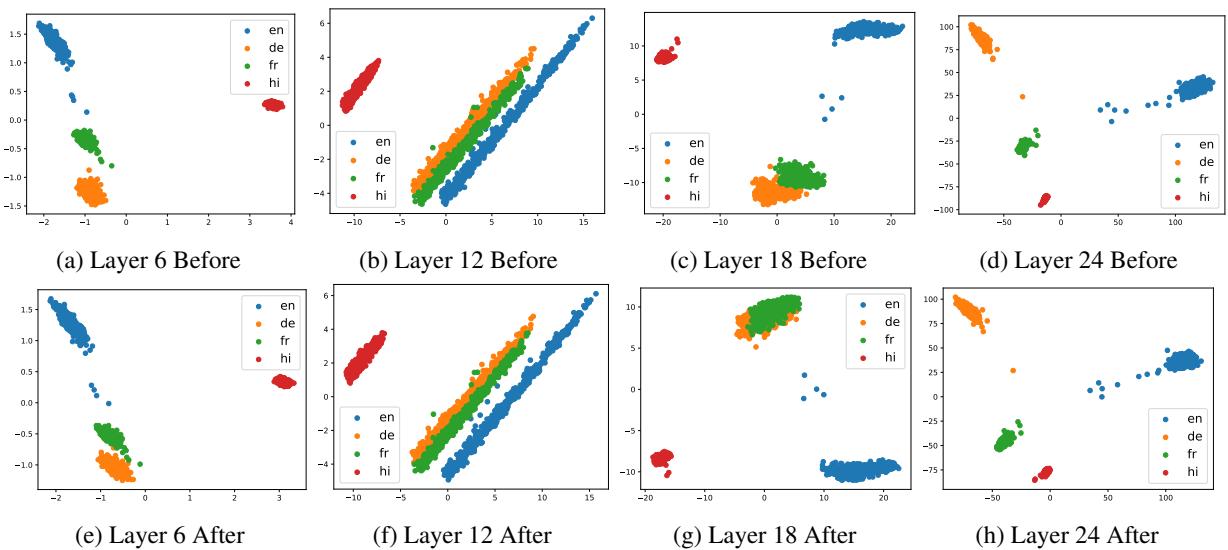

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

To further visualize this, the researchers used PCA to map the high-dimensional internal states of the model into a 2D plot. They compared how different languages (English, German, French, Hindi) are represented in the model’s layers before and after training.

Analyzing Figure 2:

- Before (Top Row): In the early layers, the languages are somewhat mixed.

- After (Bottom Row): Look at the clear separation in the bottom plots. The “clusters” for each language (colors) become distinct and well-organized.

- Disentanglement: The training allows the model to better “disentangle” the languages in its internal space. Paradoxically, while the languages become more distinct, their correlation with English increases (as shown in Pearson correlation tests in the paper), suggesting they are being better mapped to the model’s central reasoning core.

They also confirmed this pattern holds for non-English-centric models like Qwen1.5, proving that this is a general property of Large Language Models.

Conclusion

The paper “Getting More from Less” offers a compelling narrative for the future of multilingual AI. It challenges the assumption that we need massive, annotated datasets for every language we wish to support.

Key Takeaways:

- Spontaneous Learning: Training LLMs to translate questions (without answers) in just a few languages triggers a “spontaneous” improvement in reasoning capabilities across dozens of other languages.

- Latent Reasoning: The mechanism behind this seems to be the strengthening of the model’s internal “pivot” (often English or another high-resource language). The model translates the concept internally, reasons, and then translates back.

- Efficiency: This “Question Alignment” paradigm is highly efficient. It avoids the need for task-specific labels and leverages the “Superficial Alignment Hypothesis”—the idea that models already possess the knowledge from pre-training and simply need to be taught how to access it.

This research suggests that the path to truly universal language models might not be paved with more data, but with smarter, more efficient alignment strategies that unlock the potential already hiding within the weights.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.13816/images/cover.png)