Search engines have evolved dramatically, but they often suffer from a “resolution” problem. Imagine you are looking for a specific needle in a haystack. Most modern retrieval systems are great at handing you the haystack (the document or passage) but struggle to pinpoint the needle (the specific sentence or fact) without expensive re-indexing.

In the world of Information Retrieval (IR), this is known as the granularity problem. Do you index your data by document? By paragraph? By sentence? Usually, you have to choose one level of granularity and stick with it. If you choose passages, finding specific sentences becomes hard. If you choose sentences, you lose the broader context of the passage.

In this post, we are diving into a fascinating paper titled “AGRAME: Any-Granularity Ranking with Multi-Vector Embeddings”. The researchers propose a clever solution that allows a model to index data at a coarse level (like a passage) but rank results at any level of granularity (like a sentence or an atomic fact) effectively.

The Problem: The Rigidity of Granularity

To understand AGRAME, we first need to look at how modern “Dense Retrieval” works.

In standard approaches, we use models like BERT to convert text into numbers (vectors).

- Single-Vector Models (e.g., DPR, Contriever): These compress an entire passage into one single vector. While fast, this compression is “lossy.” It smears out fine details, making it hard to retrieve a specific sub-sentence fact.

- Multi-Vector Models (e.g., ColBERT): These keep a vector for every token (word) in the text. This preserves more detail but is traditionally used to rank the same unit it encoded (i.e., encode a passage, rank a passage).

The researchers identified a gap. What if we want to retrieve sentences or propositions (atomic facts) using a system built for passages?

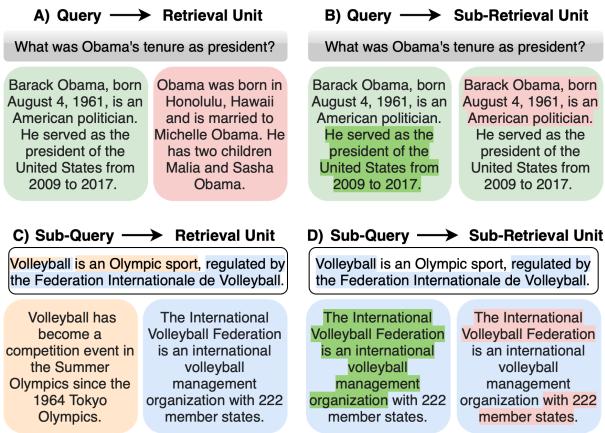

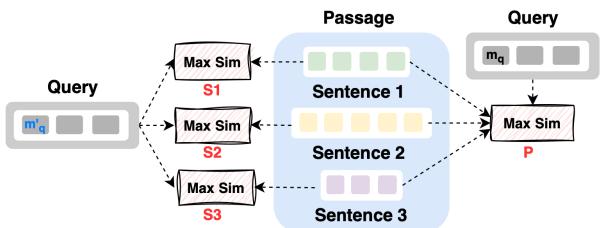

As shown in Figure 1 above, there are multiple scenarios. Standard search is (A): a query retrieves a passage. But we often need (B) (finding a specific sentence) or (D) (using a sub-part of a query to find a sub-part of a document). This flexibility is crucial for applications like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), where identifying the exact sentence that answers a question is better than retrieving a long, irrelevant block of text.

The Motivating Experiment: Why “Context” is Tricky

You might think, “If I use a powerful multi-vector model like ColBERT, can’t I just index passages and then score the sentences inside them?”

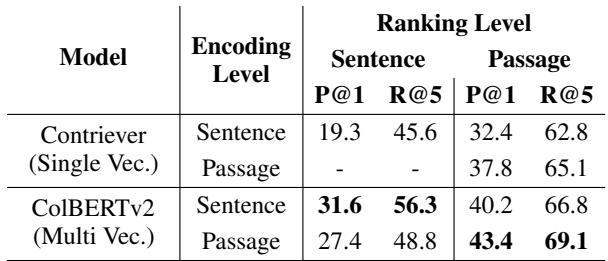

The authors tried exactly this. They took ColBERTv2, encoded passages, and then tried to rank the sentences within those passages against a query. The results were surprising.

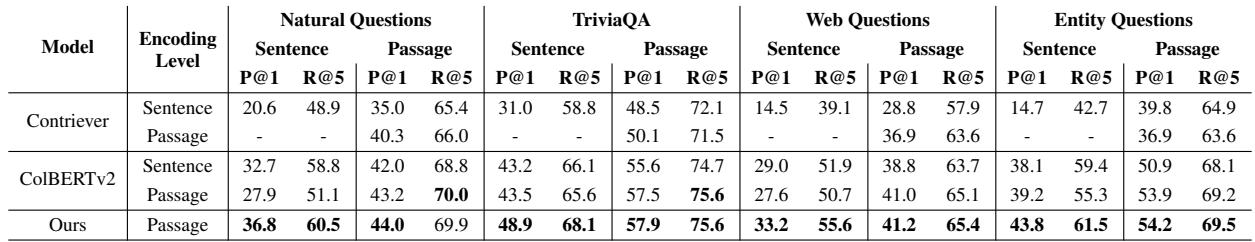

Looking at Table 1, when the model encoded at the Passage level, its ability to rank Sentences dropped significantly compared to when it encoded sentences directly (31.6 vs 27.4 in Precision@1).

Why? Because when you encode a whole passage, the embeddings for the words in a specific sentence are influenced by the surrounding text. Sometimes, the model gets confused by “distractor” sentences that share keywords with the query but don’t actually answer it.

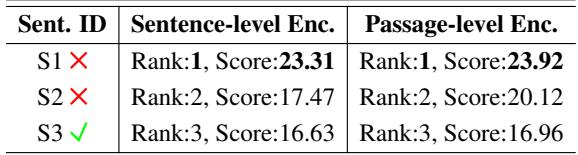

Consider the example in Table 2 below:

Here, the query is about how climate change affects marine ecosystems.

- S1 & S2 contain the words “climate change,” so the model gives them high scores.

- S3 explains the actual effects (warming waters, coral bleaching) but lacks the exact keywords “climate change.”

Consequently, the model ranks the relevant sentence (S3) last! The context provided by the passage encoding actually hurt the specific retrieval of the sentence because the model wasn’t trained to discriminate within the passage.

Enter AGRAME: Any-Granularity Ranking

The solution proposed is AGRAME (Any-Granularity Ranking with Multi-vector Embeddings). The core idea is to let the model encode at the passage level (retaining rich context) but train it to “zoom in” and score specific sub-units (sentences) accurately.

The Architecture

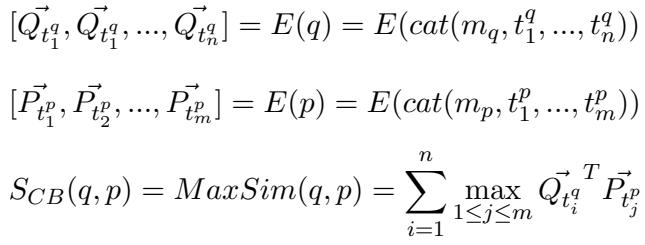

AGRAME builds upon the ColBERT architecture. In ColBERT, relevance is calculated using a “MaxSim” operation: for every word in the query, find the most similar word in the document, and sum those maximum scores.

\[ S_{CB}(q,p) = MaxSim(q,p) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \max_{1 \le j \le m} \vec{Q}_{t_i^q}^T \vec{P}_{t_j^p} \]

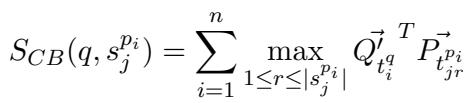

AGRAME modifies this by introducing a Granularity-Aware Query Marker.

When encoding the query, standard ColBERT adds a special token marker \(m_q\). AGRAME introduces a new marker, \(m'_q\).

- If you want to rank passages, use \(m_q\).

- If you want to rank sentences within that passage, use \(m'_q\).

This marker acts as a switch, signaling the model: “Hey, don’t just look for general relevance; look for the specific sentence that answers the query.”

As visualized in Figure 2, the passage is encoded once. To score Sentence 1 (S1), the model only computes the MaxSim interaction between the query and the tokens belonging to S1.

\[ S_{CB}(q, s_j^{p_i}) = \sum_{i=1}^n \max_{1 \le r \le |s_j^{p_i}|} \vec{Q}_{t_i^q}^T \vec{P}_{t_{jr}} \]

This allows AGRAME to utilize the rich context of the surrounding passage (because the embeddings were generated with the whole passage visible) while mathematically restricting the score to the specific sentence tokens.

Multi-Granular Contrastive Training

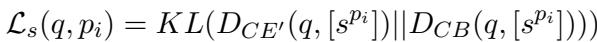

To fix the issue seen in the motivating experiment (where the model preferred keyword matching over semantic meaning), the authors introduced a new training objective.

Standard training uses a loss function that only cares if the correct passage is selected (\(\mathcal{L}_{psg}\)). AGRAME adds a sentence-level loss (\(\mathcal{L}_{sent}\)).

The researchers train a “Teacher” Cross-Encoder (\(CE'\)) specifically to identify the correct sentence within a passage. They then use Knowledge Distillation to teach AGRAME to mimic this teacher.

\[ \mathcal{L}_{s}(q, p_i) = KL(D_{CE'}(q, [s^{p_i}]) || D_{CB}(q, [s^{p_i}])) \]

This loss function forces the model to learn that—even if Sentence 1 has matching keywords—if Sentence 3 has the semantic answer, Sentence 3 should get the higher score. The final training loss combines both objectives:

\[ \mathcal{L}(q, [p]) = \mathcal{L}_{psg}(q, [p]) + \mathcal{L}_{sent.}(q, [p]) \]

Experimental Results

Does adding this “zoom-in” capability actually work? The results are compelling.

1. Sentence-Level Ranking

The authors tested AGRAME on several Open-Domain Question Answering datasets (Natural Questions, TriviaQA, etc.).

In Table 3, look at the “Ours (Passage Encoding)” row.

- On Natural Questions, AGRAME achieves a 36.8 P@1 (Precision at 1) for sentence ranking.

- Compare this to the baseline ColBERTv2 Passage encoding, which only got 27.9.

- Crucially, AGRAME even beats the model that was encoded specifically at the sentence level (32.7).

This confirms the hypothesis: Context matters. Encoding at the passage level provides better semantic information, provided you train the model (via the new loss and marker) to utilize it correctly.

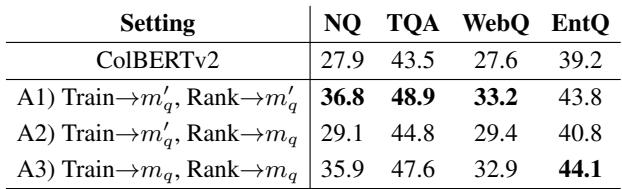

2. The Impact of the Query Marker

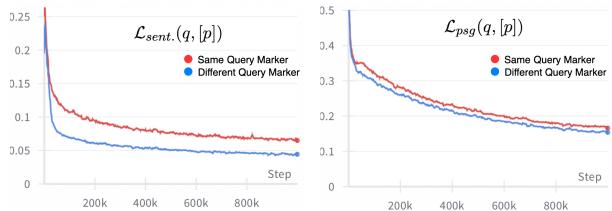

The authors also analyzed how quickly the model learns.

Figure 3 shows that using the distinct query marker (\(m'_q\)) allows the sentence-level loss (Left Graph) to drop much faster than using the same marker for both tasks. The model quickly learns to distinguish between “finding a document” and “finding a sentence.”

Revisiting the “Climate Change” failure from earlier: with AGRAME, the relevant sentence (S3) is now correctly ranked as #1.

Application: PROPCITE for Retrieval-Augmented Generation

One of the most exciting applications of AGRAME is in attribution—citing sources for AI-generated text.

Large Language Models (LLMs) often hallucinate citations. A better approach is “Post-Hoc Citation”: let the LLM generate the answer, and then use a retrieval system to find the evidence that supports each sentence.

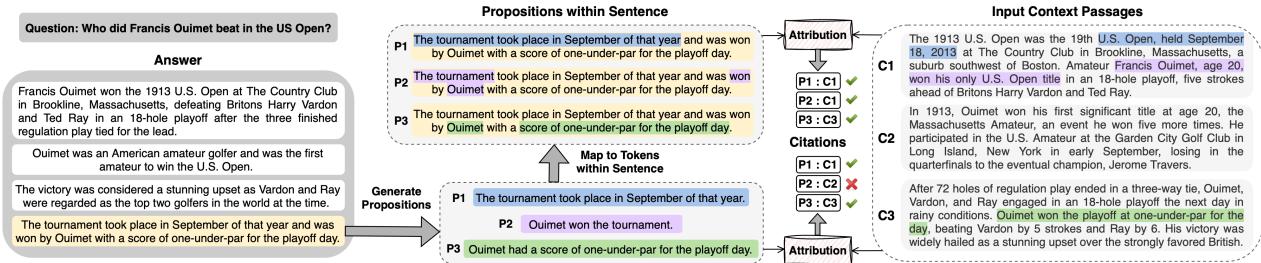

The authors propose PROPCITE. Instead of using the whole generated sentence as a query, they break the sentence down into propositions (atomic facts) and use AGRAME to find evidence for each fact individually.

As shown in Figure 4, if a generated sentence contains two facts (the tournament date and the winner), PROPCITE can attribute the date to Context C1 and the score to Context C3. A standard retriever might get confused by mixing these distinct facts into one query vector.

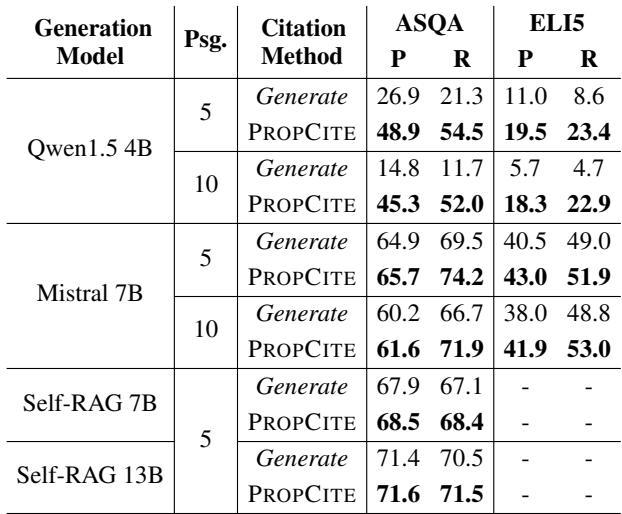

Citation Performance

The authors compared PROPCITE against standard methods where the LLM is prompted to generate citations itself (“Generate”).

Table 8 shows that PROPCITE (using AGRAME’s proposition-level ranking) achieves higher precision and recall on the ASQA and ELI5 datasets compared to prompting prompts (Generate). This is particularly valuable because it decouples the generation from the citation, allowing for more reliable, fact-checked outputs.

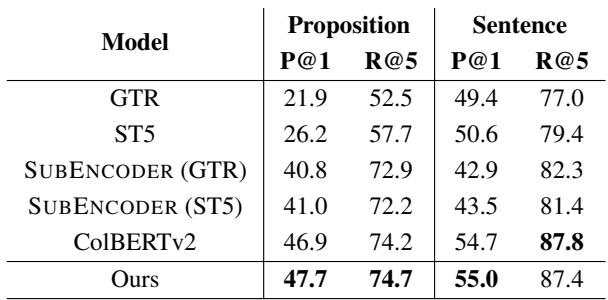

The granular ranking capability also proved superior to simpler baselines.

In the Atomic Fact Retrieval task (Table 7), AGRAME (Ours) outperforms specialized sub-sentence encoders, proving that a general-purpose multi-vector model can handle fine-grained tasks without specialized architectures.

Conclusion

The AGRAME paper presents a significant step forward in making neural search more flexible. By leveraging the token-level embeddings of multi-vector models like ColBERT, and introducing a multi-granular training strategy, the authors demonstrated that we don’t need to choose between “coarse” and “fine” search. We can have both.

Key takeaways for students and practitioners:

- Context is King: Encoding at the passage level is often better than the sentence level, even for sentence retrieval, if the model handles the context correctly.

- Multi-Vector flexibility: Unlike single-vector models that compress information, multi-vector models allow you to mathematically “mask out” parts of a document to score sub-units without re-indexing.

- Better RAG: Granular ranking allows for precise attribution (citations), which is a critical requirement for trustworthy AI systems.

AGRAME suggests a future where search indices are unified, yet the retrieval process can be as broad or as microscopic as the user needs.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.15028/images/cover.png)