Imagine you are watching a superhero movie. In the first act, the protagonist realizes a specific component in their suit is poisoning them. An hour later, they discover a new element to replace it. In the final battle, that new element powers the suit to victory.

Now, imagine I ask you: “What would have happened if the hero hadn’t replaced the component?”

To answer this, you need to connect the poisoning event from hour 0 to the victory in hour 2. You need the global context—the entire narrative arc.

For Artificial Intelligence, specifically in the field of Video Question Answering (VideoQA), this is a monumental challenge. Most current AI models are excellent at answering questions about a 10-second clip of a cat jumping. But ask them a complex causal question about a 2-hour movie, and they struggle.

In this post, we are doing a deep dive into the paper “Encoding and Controlling Global Semantics for Long-form Video Question Answering”. The researchers propose a novel architecture called GSMT (Gated State Space Multi-modal Transformer) that solves the “memory loss” problem in long videos. They also introduce two massive benchmarks, Ego-QA and MAD-QA, to truly test if machines can watch a movie and understand the plot.

The Problem: Looking Through a Keyhole

To understand the innovation of this paper, we first need to understand how standard VideoQA models work today.

Processing every single frame of a 2-hour video (which contains roughly 216,000 frames at 30fps) is computationally impossible for heavy Transformer models. The standard solution is sparse sampling or adaptive selection. The model looks at the question, scans the video quickly, and selects a handful of “relevant” clips or regions to analyze in depth.

While this saves memory, it creates a “keyhole” problem. If the model only picks 10 clips out of a movie, it loses the global semantics—the glue that holds the story together. It might see the hero fighting, but miss the scene an hour earlier explaining why they are fighting.

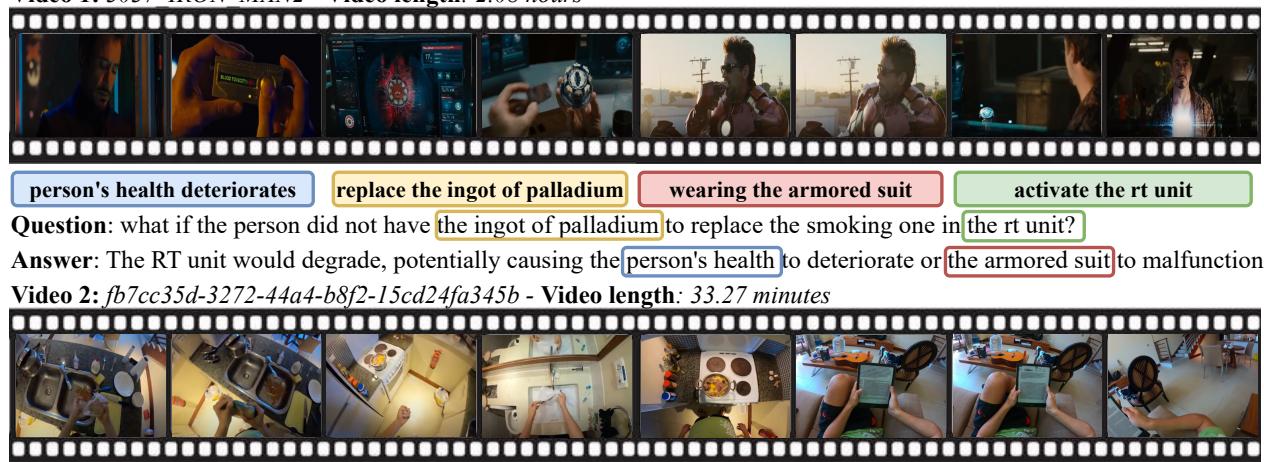

As shown in Figure 1 above, answering a question like “What if the person did not have the ingot of palladium?” requires reasoning over a long chain of events: degradation of health \(\rightarrow\) need for replacement \(\rightarrow\) creating the new element \(\rightarrow\) activating the suit. Standard selection methods often fail to capture this entire chain.

The Solution: Gated State Space Multi-modal Transformer (GSMT)

The researchers propose a new framework that doesn’t just “skip” to the good parts. Instead, it processes the entire video sequence to extract a global context signal before any selection happens.

They achieve this using a State Space Layer (SSL). Unlike Transformers, which have quadratic complexity (\(O(L^2)\)) regarding sequence length, State Space Models (SSMs) scale linearly (\(O(L)\)). This allows the model to “watch” the whole video and encode a long-term memory without crashing the GPU.

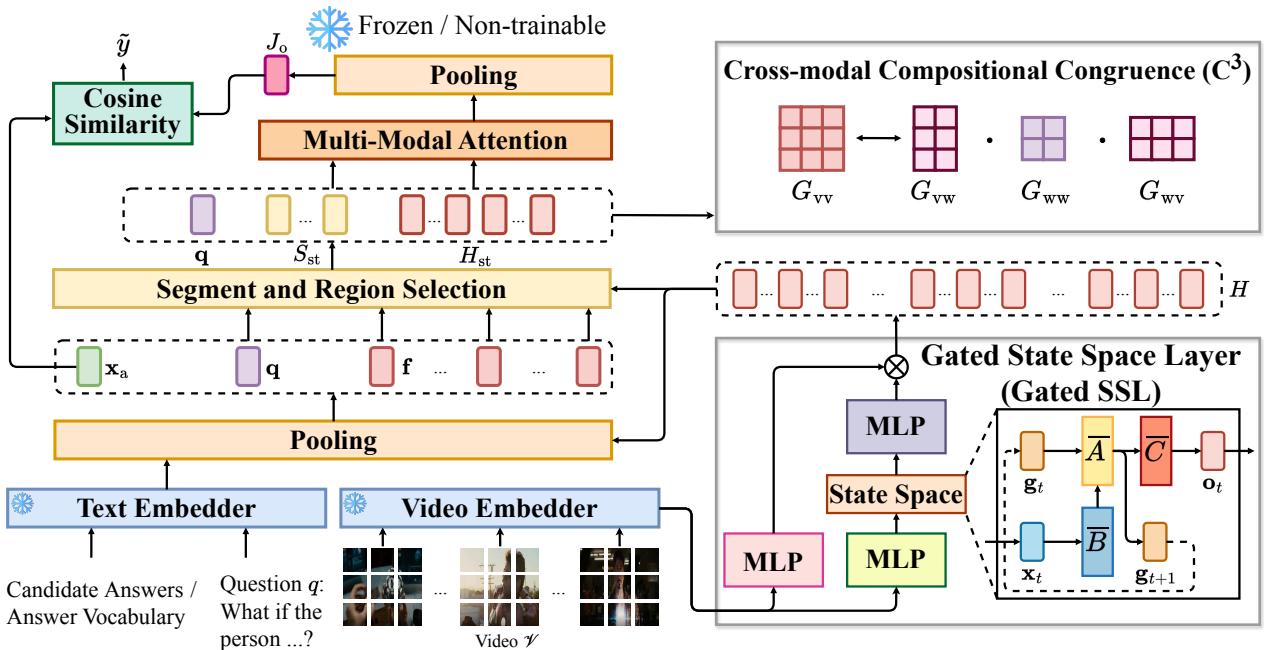

Here is the high-level architecture of the GSMT:

The architecture has three main phases:

- Gated State Space Layer (SSL): Encodes the global video history into the visual features.

- Selection Module: Uses the question to pick the most relevant segments (now enriched with global context).

- Multi-Modal Attention: Uses a Transformer to perform deep reasoning on the selected segments.

Let’s break these down step-by-step.

1. The Gated State Space Layer (SSL)

The core innovation here is the use of State Space Models to capture long-term dependencies. If you are familiar with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Hidden Markov Models, the concept is similar: we have a hidden state that updates over time.

The Mathematics of Memory

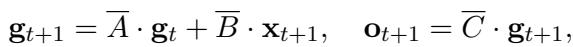

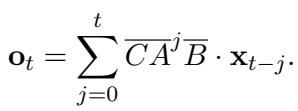

The authors define a continuous mapping from input visual patches \(x(t)\) to an output \(y(t)\) via a hidden state \(g(t)\). In the discrete domain (which computers use), this is parameterized by matrices \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\).

The update rule for the hidden state is:

Here, \(\mathbf{g}_t\) is the “memory” at time \(t\), and \(\mathbf{x}_{t+1}\) is the new visual input. The matrix \(\bar{A}\) determines how much of the old memory is kept, and \(\bar{B}\) determines how much of the new input is added.

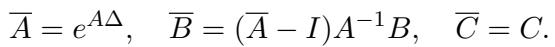

To make this computationally feasible, the continuous parameters are discretized using a step size \(\Delta\):

The beauty of this formulation is that it can be unrolled. Instead of calculating it step-by-step (like an RNN, which is slow), it can be written as a convolution:

This convolution allows the model to compute the “memory” for the entire video in parallel using Fast Fourier Transforms (FFT). This is what makes the global encoding fast enough for long videos.

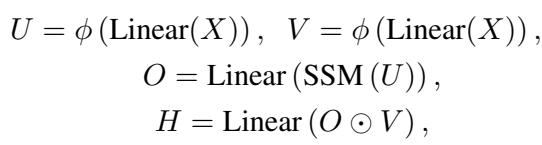

Controlling the Flow: The Gating Mechanism

However, simply remembering everything in a 2-hour movie is not ideal. A lot of a movie is background noise—scenery, silence, or irrelevant motion. If the global memory is flooded with noise, the reasoning suffers.

To fix this, the authors introduce a Gating Unit. This acts like a valve, controlling how much of the global semantic information flows into the final visual representation.

They compute two gating signals, \(U\) and \(V\), and the output \(O\) from the SSM:

Here, the output of the State Space Model (\(O\)) is multiplied element-wise (\(\odot\)) by the gate \(V\). This allows the network to learn to suppress irrelevant global information and highlight the important narrative threads.

2. Smart Selection and Attention

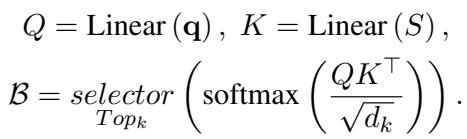

Once the visual features are enriched with this global context via the Gated SSL, the model proceeds to the selection phase. Because the features now contain information about the whole video (thanks to SSL), the selection module makes smarter decisions.

The model pools frames into segments and selects the top-\(k\) segments most relevant to the question \(\mathbf{q}\).

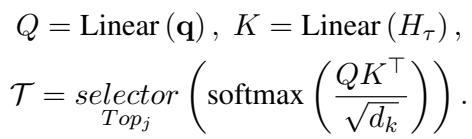

After selecting segments, it dives deeper, selecting specific spatial regions (patches) within those frames using a similar top-\(j\) selection mechanism:

Finally, these selected, high-quality visual tokens are fed into a standard Transformer alongside the text for the final answer prediction.

Aligning Vision and Language: The \(C^3\) Objective

The architecture alone is powerful, but the authors introduce a specialized training objective to make it even better. They call it Cross-modal Compositional Congruence (\(C^3\)).

The intuition is this: If the question asks about a “man holding a cup,” the relationship between the word “man” and “cup” in the text should mirror the relationship between the visual patch of the man and the visual patch of the cup.

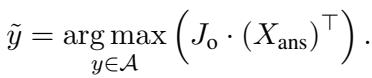

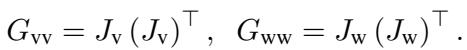

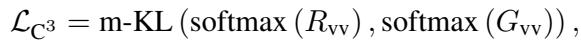

The model computes attention matrices for vision (\(G_{vv}\)) and language (\(G_{ww}\)), and the cross-modal attention (\(G_{vw}\)).

They then project the visual attention into the language space using a change-of-basis formulation:

The objective is to minimize the difference (Kullback-Leibler Divergence) between the original visual relations and this projected version. This forces the visual features to organize themselves in a way that is “congruent” with the linguistic structure of the question.

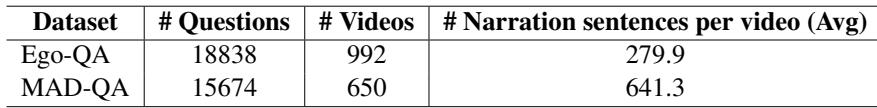

Redefining “Long-Form”: Ego-QA and MAD-QA

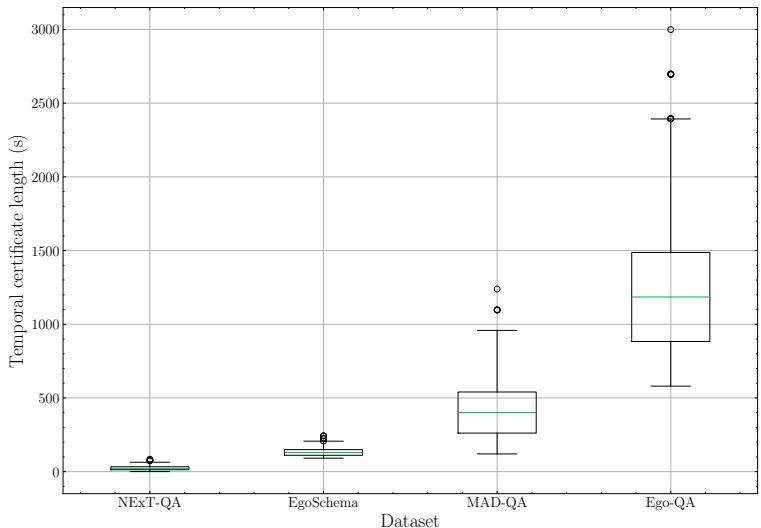

One of the most critical contributions of this paper is pointing out that existing “long-form” datasets aren’t actually that long. Datasets like NExT-QA or EgoSchema often have clips averaging a few minutes.

To rigorously test their model, the authors created two massive new benchmarks:

- Ego-QA: Based on Ego4D. Average video length: 17.5 minutes.

- MAD-QA: Based on movies (MAD dataset). Average video length: 1.9 hours.

They used GPT-4 to generate complex questions based on dense captions, followed by strict human filtering to ensure the questions actually required watching the video.

As seen in Figure 6 below, the “temporal certificate length” (how much of the video you actally need to watch to answer the question) is significantly higher for these new datasets compared to existing ones like NExT-QA.

Experiments and Results

So, does adding a Gated State Space Layer actually work? The results are compelling.

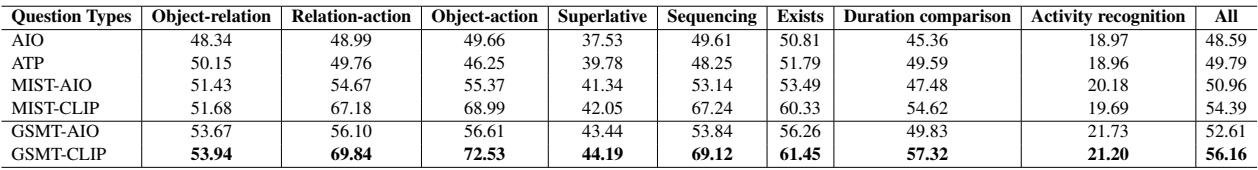

Performance on Standard Datasets

First, let’s look at AGQA, a standard benchmark for spatio-temporal reasoning. GSMT outperforms the previous state-of-the-art (MIST-CLIP) across almost all question types, particularly “Sequence” and “Object-action” questions which rely heavily on context.

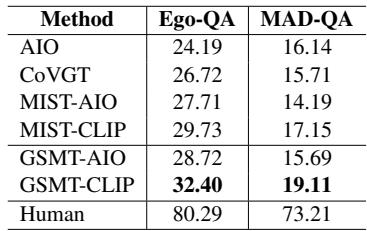

Performance on the New “True” Long-Form Datasets

The gap becomes even more apparent on the difficult, massive datasets the authors created.

On Ego-QA, GSMT (32.40%) significantly outperforms the previous best MIST-CLIP (29.73%). On MAD-QA (the movie dataset), the improvement is also clear, though the overall numbers are lower, reflecting the extreme difficulty of reasoning over 2-hour movies.

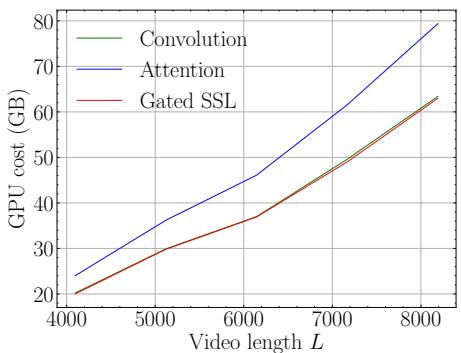

Efficiency: The SSL Advantage

You might think that processing the whole video history would be too expensive. However, because of the linear scaling of State Space Models, the memory cost is very manageable compared to standard attention mechanisms.

Figure 4 below shows the GPU memory cost as video length increases. The Blue line (Attention) shoots up exponentially. The Red line (Gated SSL) scales linearly, similar to convolution, making it feasible to process thousands of frames.

Qualitative Analysis

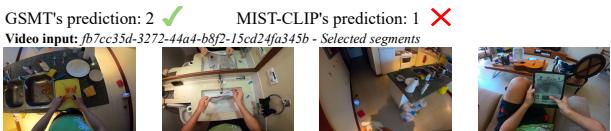

Let’s look at a concrete example from the MAD-QA dataset (Iron Man 2).

The question asks: “What if the person did not have the ingot of palladium to replace the smoking one in the rt unit?”

- Option 0: Man would have rushed to hospital for different reason.

- Option 1: Romance would not have started.

- Option 3 (Correct): The RT unit would degrade, health deteriorates/suit malfunctions.

The baseline model (MIST-CLIP) gets confused and predicts Option 1. It likely focuses on localized frames of characters talking. GSMT, however, correctly predicts Option 3. By encoding the global semantics, it links the palladium (seen early in the movie) to the health of the protagonist (seen throughout) and the function of the suit (seen in the climax).

Another example from Ego-QA:

The question asks for the “central theme” of a 30-minute video. MIST-CLIP predicts “Physical and mental self-improvement” (perhaps seeing a yoga mat). GSMT correctly identifies “Routine household management” by aggregating cues from the kitchen, cleaning, and organizing scenes over the full duration.

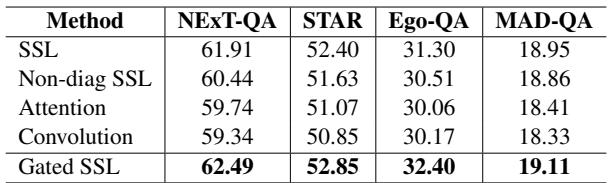

Ablation Studies: What Matters?

The authors performed rigorous testing to see which components mattered most.

- Does Gating Matter? Yes. Removing the gating mechanism (Standard SSL) dropped performance significantly (Table 7). The model needs to filter noise.

- Does the \(C^3\) Objective Matter? Yes. Using the alignment objective improved accuracy by roughly 1-2% across datasets compared to not using it or using standard Optimal Transport methods (Table 8).

- Does Position Matter? Yes. The SSL must be placed early in the network (Video Embedder) to enrich features before selection. Placing it later (Multi-modal stage) hurts performance (Table 10).

Conclusion

The paper “Encoding and Controlling Global Semantics for Long-form Video Question Answering” makes a compelling case that we cannot solve long-form video understanding by simply “skimming” efficiently. We need memory.

By integrating Gated State Space Layers, the GSMT architecture offers a way to retain the global narrative of a video without the exploding computational costs of Transformers. Furthermore, the introduction of Ego-QA and MAD-QA pushes the field toward realistic, hour-long video understanding rather than short-clip analysis.

As AI assistants become more integrated into our lives—analyzing our day-to-day logs or helping us search through movie archives—capabilities like those demonstrated by GSMT will be essential. The ability to connect the dots across hours of footage brings us one step closer to AI that truly understands the “big picture.”

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2405.19723/images/cover.png)