Introduction

In the world of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), data is king. To build a model that understands medical dictation, legal proceedings, or casual slang, you typically need thousands of hours of recorded audio paired with accurate transcripts. But for many specific domains, this “real” paired data simply doesn’t exist or is prohibitively expensive to collect.

The modern solution is clever: use Text-to-Speech (TTS) systems to generate synthetic audio from text. If you have the text of a medical textbook, you can generate thousands of hours of synthetic speech to train your model. However, there is a catch. No matter how advanced TTS becomes, it still possesses acoustic artifacts—lack of background noise, unnatural breathing patterns, or specific digital signatures—that differentiate it from human speech.

When an ASR model is trained on this synthetic data, it suffers from the synthetic-to-real gap. It learns to recognize the perfect diction of a robot but fails when presented with the messy reality of human speech.

In a recent paper, Task Arithmetic can Mitigate Synthetic-to-Real Gap in Automatic Speech Recognition, researchers propose a fascinating solution that doesn’t require more real data in the target domain. Instead, they use Task Arithmetic. By treating model weights as vectors, they can mathematically calculate the “direction” of real speech and inject it into a model trained on synthetic data.

The Landscape of Domain Adaptation

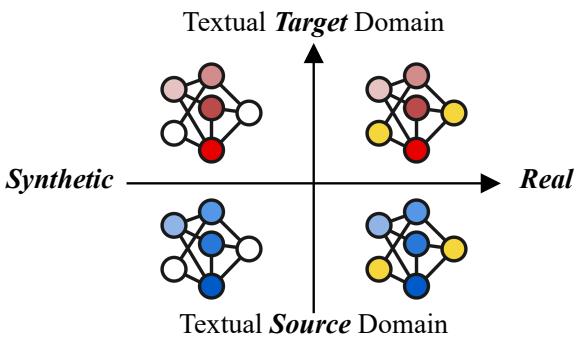

To understand the solution, we must first visualize the problem. Domain adaptation in ASR faces two distinct types of mismatches:

- Textual/Topic Mismatch: The difference between what is being discussed (e.g., cooking recipes vs. weather reports).

- Acoustic Mismatch: The difference in how the audio sounds (e.g., synthetic speech vs. real human speech).

The researchers visualize these shifts in a quadrant system:

As shown in Figure 2, we often start with a Source Domain (top left and bottom left) where we have plenty of data—both synthetic and real. We want to move to a Target Domain (bottom right) where we want the model to perform well on real speech. However, in the target domain, we usually only have text, meaning we can only generate Target Synthetic data (top right).

The goal is to bridge the gap from the Target Synthetic quadrant to the Target Real quadrant without actually possessing real audio data for that target.

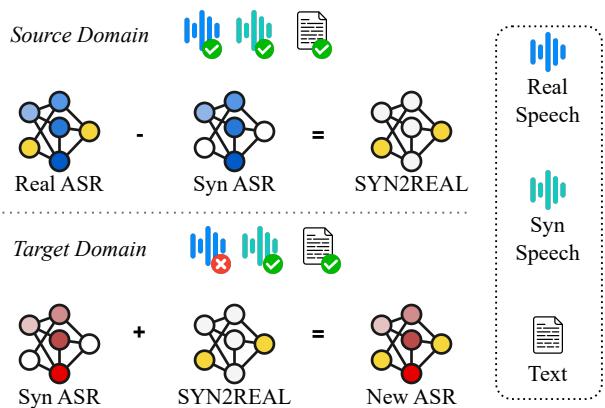

The Core Method: SYN2REAL Task Vector

The researchers propose a method called SYN2REAL. The intuition is elegant: if we can figure out exactly how “real speech” differs from “synthetic speech” in a domain where we do have data, we can package that difference and apply it to a new domain where we don’t.

This is made possible by Task Arithmetic. Recent findings in deep learning suggest that the weights of fine-tuned neural networks can be manipulated using basic arithmetic operations (addition and subtraction).

Step 1: Calculating the Difference

First, the method utilizes a Source Domain where both real recordings and synthetic generations exist. Two separate models are fine-tuned from the same pre-trained ASR backbone (like Whisper):

- \(\theta_{real}^S\): A model fine-tuned on Real source data.

- \(\theta_{syn}^S\): A model fine-tuned on Synthetic source data.

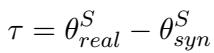

The researchers hypothesize that the difference between these two models’ parameters represents the specific acoustic characteristics required to understand real speech. They define this difference as the Task Vector (\(\tau\)):

Here, \(\tau\) (tau) encodes the “direction” one must travel in the parameter space to convert a synthetic-trained model into a real-trained model.

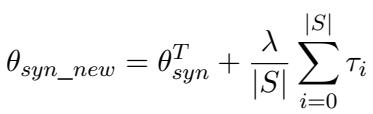

Step 2: Applying the Vector to the Target

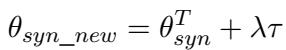

Next, the researchers take the Target Domain (e.g., a specific topic like “Cooking” where no real audio exists). They generate synthetic audio using TTS and fine-tune a model on it, resulting in \(\theta_{syn}^T\).

Normally, this model (\(\theta_{syn}^T\)) would perform poorly on real humans because it has overfit to the synthetic TTS voice. To fix this, the researchers add the previously calculated Task Vector (\(\tau\)) to this target model.

In this equation:

- \(\theta_{syn\_new}\) is the parameters of the final adapted model.

- \(\lambda\) (lambda) is a scaling factor that controls how strongly we apply the correction.

Visualizing the Transformation

This process can be visualized geometrically. Imagine the model’s parameters as coordinates on a map.

As seen in Figure 3, the vector \(\tau\) represents the specific shift from Source Synthetic (\(\theta_{syn}^S\)) to Source Real (\(\theta_{real}^S\)). By applying this same vector to the Target Synthetic model (\(\theta_{syn}^T\)), we push the model toward a theoretical “Target Real” space, effectively “steering” the weights to handle real acoustic features.

A high-level overview of the entire pipeline is demonstrated below:

Figure 1 summarizes the flow: The “Source Domain” provides the map (the vector), and the “Target Domain” uses that map to navigate from synthetic training to real-world performance.

Experimental Results

To prove this theory, the authors tested the method on the SLURP dataset, which contains commands for a virtual assistant across 18 distinct domains (e.g., email, cooking, music).

They treated one domain as the “Target” (unseen real data) and the other 17 as “Source” data. They used popular TTS models like BARK and SpeechT5 to generate the synthetic data.

Does it actually reduce errors?

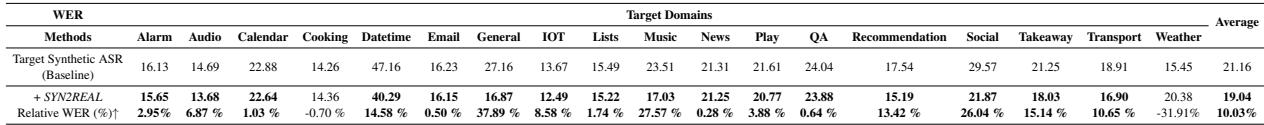

The primary metric used was Word Error Rate (WER)—lower is better.

Table 1 shows the results. The “Target Synthetic ASR” (Baseline) often struggled, with high error rates. However, adding the SYN2REAL vector consistently improved performance.

- Average Improvement: The method yielded a 10.03% relative reduction in WER on average.

- Specific Wins: Domains like “Music” and “Social” saw massive improvements (over 25% relative reduction), suggesting the vector effectively captured acoustic nuances that simple synthetic training missed.

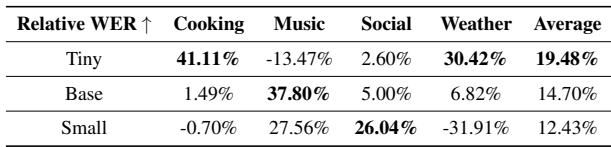

Impact of Model Size

Does this only work on massive models, or can smaller efficient models benefit too? The researchers tested Whisper models of various sizes: Tiny, Base, and Small.

Table 2 reveals an interesting trend. While all models benefited, the Base model showed the most consistent improvement across domains (14.70%). The Tiny model was more volatile—improving massively in “Cooking” but actually degrading in “Music.” This suggests that very small models might be less stable when undergoing arithmetic weight manipulation.

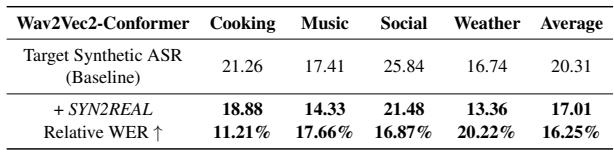

Works on Different Architectures

To ensure this wasn’t just a quirk of the Whisper architecture, they tested it on Wav2Vec2-Conformer.

As shown in Table 3, the method successfully transferred to the Wav2Vec2 architecture, achieving a 16.25% average relative improvement. This indicates that the principle of “acoustic vectors” is a fundamental property of neural networks trained on speech, not just a specific model feature.

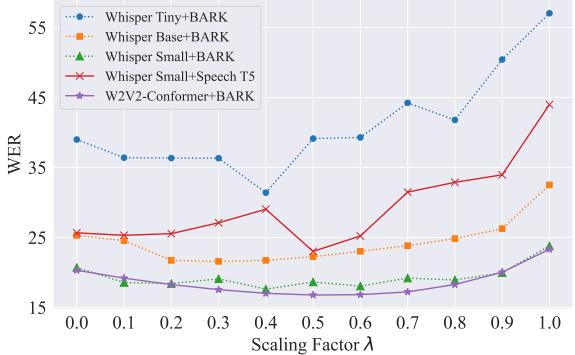

The Importance of Scaling (\(\lambda\))

One of the most critical hyperparameters in Task Arithmetic is \(\lambda\) (lambda)—the scaling factor. This determines how much of the “Real” vector is added to the model.

- If \(\lambda\) is too low, the model stays optimized for synthetic speech.

- If \(\lambda\) is too high, the weights are distorted, and the model breaks.

Figure 4 displays the relationship between the scaling factor and WER. Most models exhibit a U-shaped curve, with the “sweet spot” typically falling between 0.3 and 0.6. This confirms that while the direction of the vector is correct, the magnitude needs to be carefully tuned to avoid overriding the textual knowledge the model learned during synthetic training.

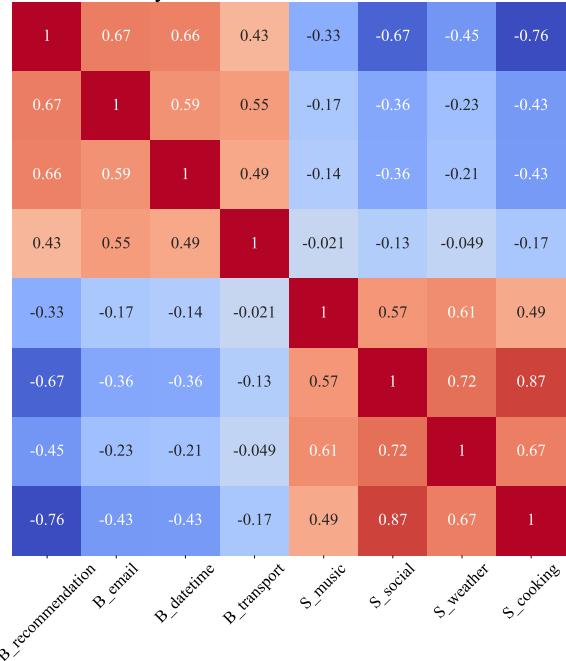

Analyzing the Vectors

Finally, the researchers asked: Do these vectors actually mean anything, or are they just random noise? They generated task vectors using different TTS systems (BARK vs. SpeechT5) and compared them using cosine similarity.

The heatmap in Figure 5 shows high similarity between vectors from corresponding domains. This confirms that the vectors are indeed capturing consistent, meaningful acoustic information regarding the gap between synthetic and real speech.

Advanced Technique: The Ensemble Approach

The researchers explored an even more granular approach called SYN2REAL Ensemble. Instead of calculating one giant vector from all source data, they calculated individual vectors for each source domain (e.g., a vector for “Email,” a vector for “News,” etc.) and then averaged them.

This ensemble method resulted in an even higher performance boost (up to 18.25% relative improvement), likely because averaging multiple specific vectors filters out domain-specific noise and isolates the pure “synthetic-to-real” acoustic signal.

Conclusion and Implications

The “Synthetic-to-Real Gap” has long been a barrier to deploying ASR models in niche domains where data is scarce. The standard approach—just training on synthetic data—often yields models that fail in the real world.

This paper provides a computationally efficient solution. By using Task Arithmetic, we can “borrow” the acoustic characteristics of real speech from resource-rich domains and mathematically inject them into resource-poor domains.

Key Takeaways:

- Efficiency: This method does not require collecting new real data for the target domain.

- Generality: It works across different model architectures (Whisper, Wav2Vec2) and TTS engines.

- Simplicity: The core operation is simple subtraction and addition of weights, making it easy to implement in existing pipelines.

As we move toward a future where models are adapted on the fly for specific tasks, techniques like Task Arithmetic represent a shift away from brute-force training and toward a more elegant, mathematical manipulation of machine intelligence.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.02925/images/cover.png)