Imagine you are chatting with a friend about a movie. You ask, “Who directed Inception?” They answer, “Christopher Nolan.” Then you ask, “What other movies did he do?”

Your friend instantly understands that “he” refers to Christopher Nolan. But for a search engine, that second question is a nightmare. “He” could be anyone. To get a good answer, a search system needs to rewrite your question into something standalone, like “What other movies did Christopher Nolan direct?”

This process is called Conversational Query Rewriting (CQR). Until recently, the best way to solve this was throwing the conversation history into a massive, closed-source model like GPT-4 (ChatGPT) and asking it to fix the sentence. It works, but it’s expensive, slow, and relies on proprietary APIs.

But what if open-source models—which are smaller and free to run—could do just as well?

In this post, we are diving deep into CHIQ (Contextual History Enhancement for Improving Query Rewriting), a research paper from the Université de Montréal and Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab. The authors propose a clever two-step method that allows open-source models (like LLaMA-2) to achieve state-of-the-art results in conversational search, often beating systems that rely on commercial giants.

The Problem: The “Context” Trap

In conversational search, the user’s intent is rarely in the current sentence alone; it is buried in the history of the conversation.

Traditional methods try to solve this by training a model to take the history (\(H\)) and the current utterance (\(u_{n+1}\)) and output a rewritten query (\(q_{n+1}\)).

In this equation, \(\mathcal{I}^{CQR}\) is the instruction prompt. The problem is that open-source models (like the 7B parameter versions of LLaMA or Mistral) historically struggle with this direct task when the conversation gets complex. They might miss a coreference (linking “he” to “Nolan”) or get confused by a topic switch.

Closed-source models compensate for the messy history with sheer reasoning power. The authors of CHIQ hypothesized that if we could “clean up” the history before asking the model to rewrite the query, open-source models could perform just as well as their commercial counterparts.

The Solution: CHIQ

The core philosophy of CHIQ is Contextual History Enhancement. Instead of asking the Large Language Model (LLM) to “figure it out” from a messy transcript, CHIQ uses the LLM to first refine the history into a clear, unambiguous context.

The researchers identified five specific types of ambiguity in conversations and designed five prompt-based strategies to fix them.

Step 1: Cleaning the History

Before generating a search query, CHIQ processes the conversation history through these five enhancement modules. This leverages the basic NLP capabilities that even smaller open-source models excel at.

1. Question Disambiguation (QD)

Users often use acronyms or vague references. The QD module rewrites previous user questions to be self-contained.

- Original: “What about the FDA?”

- Enhanced: “What is the stance of the Food and Drug Administration?”

2. Response Expansion (RE)

System responses in a chat are often short (“Yes, he did.”). Brief answers are great for humans but terrible for search models looking for keywords. The RE module prompts the LLM to expand the previous answer into a full sentence rich with context.

3. Pseudo Response (PR)

This is a fascinating addition. Sometimes, the search system needs to anticipate the answer to the current question to find the right documents. The PR module asks the LLM to hallucinate (educated guess) a potential answer. Even if the facts aren’t 100% correct, the vocabulary generated helps the retriever match relevant documents.

4. Topic Switch (TS)

Conversations drift. If you were talking about “Inception” and suddenly ask “What’s the weather in Paris?”, the previous history about movies is now noise. The TS module explicitly asks the LLM: “Is this a new topic?”

- If Yes: The history is truncated, removing irrelevant previous turns.

- If No: The history is kept.

5. History Summary (HS)

Long conversations exceed the token limits of models and introduce noise. The HS module summarizes the entire interaction into a concise paragraph, preserving only the key information needed for the next turn.

Step 2: Generating the Query (Three Flavors)

Once the history is enhanced (cleaned, expanded, and summarized), how do we actually get the search query? The paper proposes three approaches.

Method A: CHIQ-AD (Ad-hoc Query Rewriting)

This is the most direct method. The system simply prompts the LLM using the Enhanced History instead of the original raw text. It combines the enhancements (usually Question Disambiguation + Response Expansion + Pseudo Response) and asks the LLM to write the final search query.

Method B: CHIQ-FT (Search-Oriented Fine-Tuning)

This approach is designed for efficiency. Running an LLM (even a 7B one) for every single search query can be slow. CHIQ-FT uses the LLM offline to create a massive training dataset, which is then used to fine-tune a much smaller, faster model (like T5-base).

However, they don’t just use any rewritten query for training. They use a “Search-Oriented” selection process.

Here is how they create the training data:

- They feed the Enhanced History (\(\mathcal{H}'\)), the user question (\(u_{n+1}\)), and—crucially—the actual correct document (gold passage, \(p_{n+1}^*\)) to the LLM.

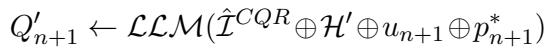

- The LLM generates multiple potential queries (\(Q'_{n+1}\)).

- The system tests these queries against a retrieval engine. It selects the specific query (\(q'\)) that results in the highest retrieval score (\(S\)) for the correct document.

This process ensures that the smaller model is trained on queries that are proven to work for search, not just queries that look linguistically correct.

Method C: CHIQ-Fusion

Why choose one? CHIQ-Fusion runs both the Ad-hoc method (CHIQ-AD) and the Fine-tuned method (CHIQ-FT). It retrieves two lists of documents and merges them. This turns out to be highly effective because the two methods often find complementary information.

Experimental Results

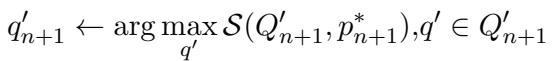

The researchers tested CHIQ on five standard benchmarks, including TopiOCQA (which features frequent topic switching) and QReCC. They compared their open-source LLaMA-2-7B implementation against systems using ChatGPT and other sophisticated retrievers.

The results were impressive.

Let’s break down Table 1:

- State-of-the-Art for Open Source: CHIQ-Fusion (and often CHIQ-AD alone) significantly outperforms previous methods that fine-tune small models (like T5QR or ConvGQR).

- Beating Closed Source: On TopiOCQA, CHIQ-Fusion (MRR 47.2) outperforms LLM-Aided (MRR 43.9), which uses ChatGPT-3.5. This is a major win, showing that a 7B model with better data prep can beat a 175B+ model.

- The Power of Fusion: You can see that CHIQ-Fusion consistently yields the highest scores (indicated by the Bold numbers). This confirms that the Ad-hoc LLM reasoning and the Fine-tuned T5 pattern matching find different relevant documents.

Case Studies: Why Does It Work?

To understand why CHIQ performs so well, we need to look at specific examples where standard rewriting fails but CHIQ succeeds.

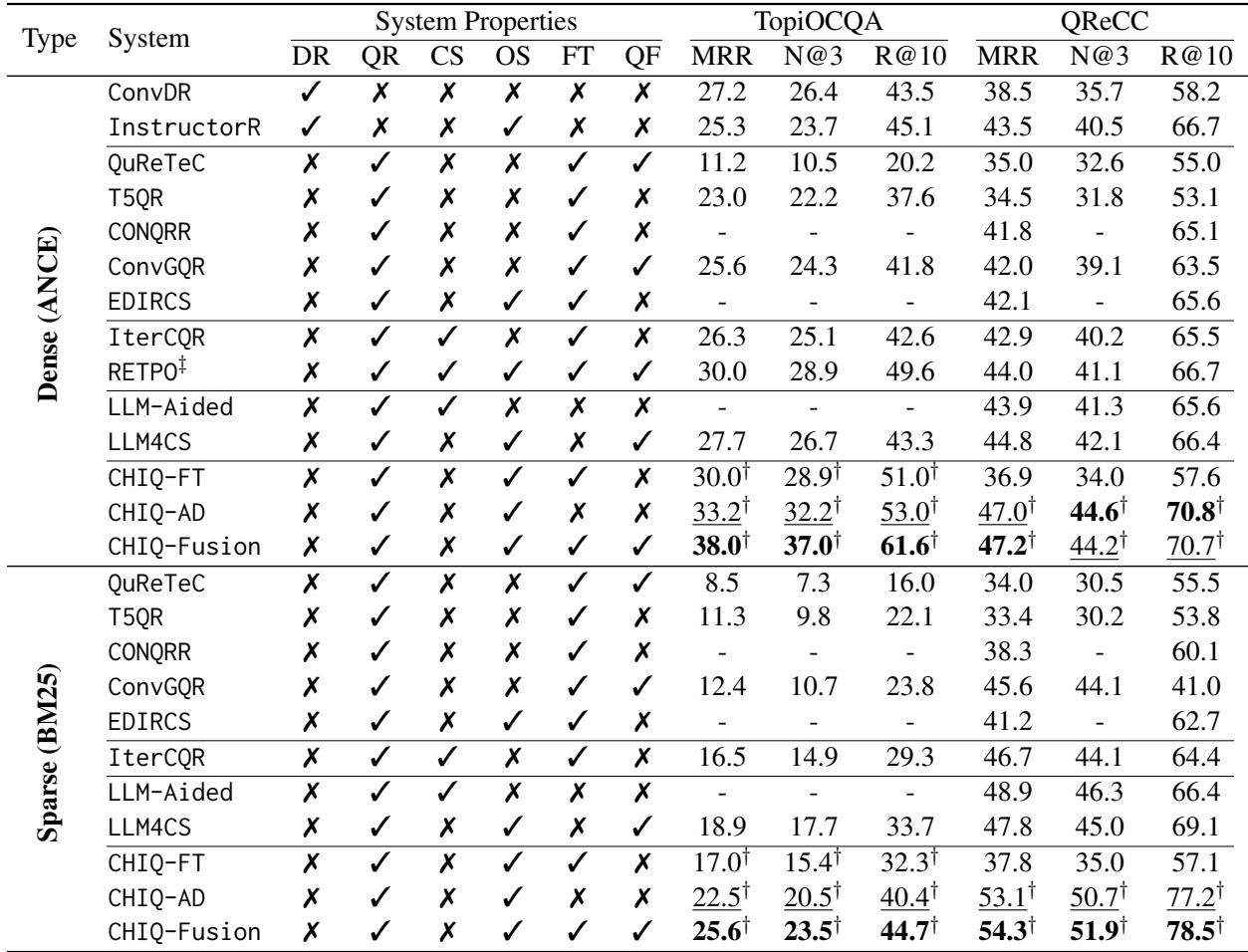

Case Study 1: The Biology Query

In this example (Table 9), the user asks a complex chain of questions about human metabolism.

- The Problem: The user asks, “What is the emotional response due to the third one?”

- Standard Rewrite (LLM-QR): “What is the emotional response associated with the third hormone?”

- Result: Rank 41. The search engine doesn’t know which hormone is “the third one” because the list was in the previous turn.

- CHIQ Enhancement:

- HS (History Summary): Explicitly lists “Cortisol, glucagon, adrenaline…”

- CHIQ-FT Query: “How does adrenaline impact mood?”

- Result: Rank 3. By resolving “the third one” to “adrenaline” before rewriting, the system found the right document.

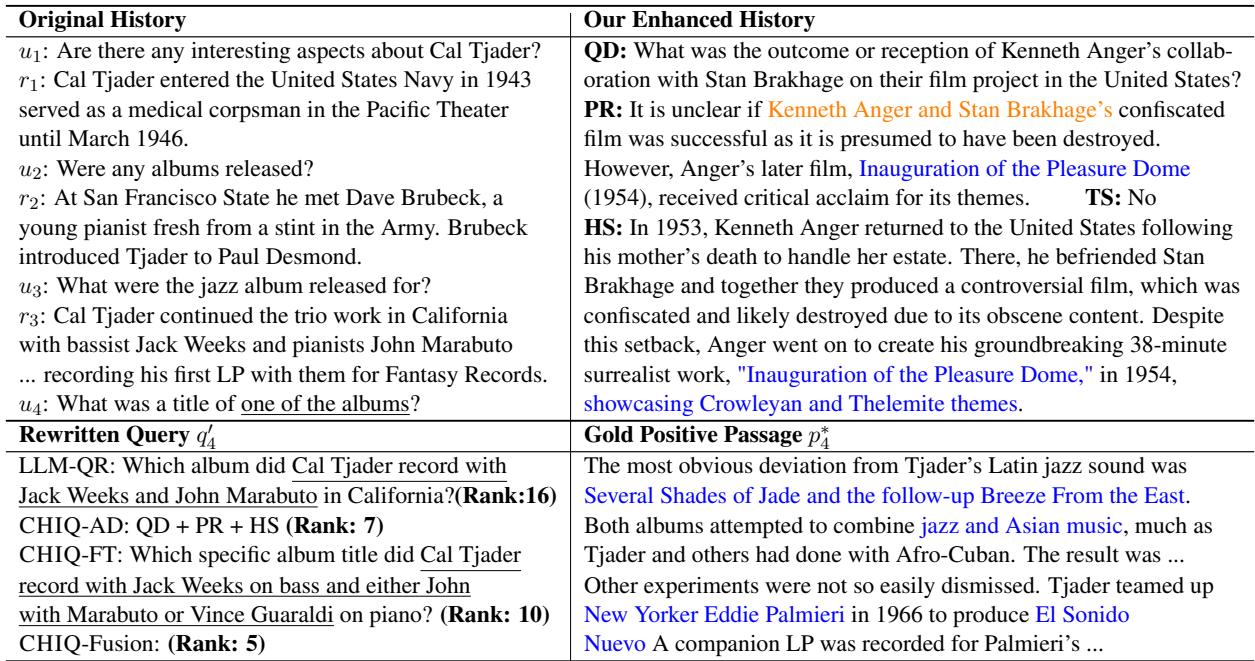

Case Study 2: The Jazz Musician

In Table 10, the user asks about albums by Cal Tjader.

- The Problem: The conversation is long and mentions various collaborators.

- Standard Rewrite: “Which album did Cal Tjader record with Jack Weeks…?” (Rank 16).

- CHIQ Enhancement: The Pseudo Response (PR) module hallucinates/predicts relevant titles like “Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.” Even if the prediction is slightly off, it primes the context with album-related vocabulary.

- CHIQ-Fusion Result: Rank 5.

Implications and Future Outlook

The CHIQ paper is a significant step forward for democratizing conversational search. Here are the key takeaways:

- Data Quality > Model Size: You don’t always need a larger model. Sometimes, you just need to feed your smaller model better inputs. By enhancing the history, LLaMA-2-7B punched way above its weight class.

- Modularity Matters: Breaking the complex task of “rewriting” into smaller sub-tasks (disambiguation, expansion, summarization) makes it easier for open-source models to reason correctly.

- Efficiency: The CHIQ-FT method shows that we can use powerful LLMs to train efficient, smaller models that can be deployed in production environments with lower latency.

CHIQ demonstrates that the gap between open-source and closed-source LLMs in complex tasks can be bridged not just by training bigger models, but by designing smarter pipelines. For students and researchers, this opens up exciting avenues to build powerful search assistants without relying on costly proprietary APIs.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.05013/images/cover.png)