Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of Large Language Models (LLMs), a new “reasoning strategy” seems to drop every week. We’ve moved far beyond simple prompts. We now have agents that debate each other, algorithms that build “trees” of thoughts, and systems that reflect on their own errors to self-correct.

Papers introducing these methods often show impressive tables where their new, complex strategy dominates the leaderboard, leaving simple prompting techniques in the dust. But there is a catch—a hidden variable that is often overlooked in academic comparisons: Compute Budget.

Imagine comparing two students on a math test. Student A answers immediately. Student B is allowed to write out ten drafts, consult three friends, and take an hour longer. If Student B scores slightly higher, are they smarter, or did they just have more resources?

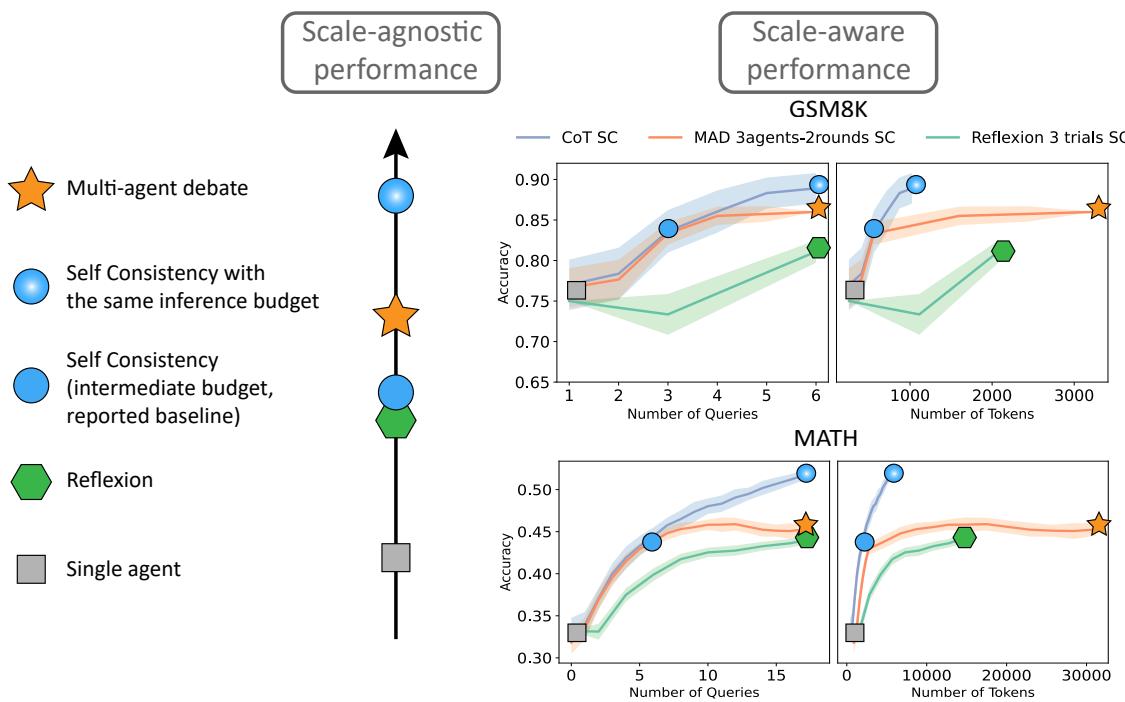

This is the core question behind the research paper “Reasoning in Token Economies: Budget-Aware Evaluation of LLM Reasoning Strategies.” The authors argue that traditional evaluations are “scale-agnostic,” meaning they ignore the cost of inference. When we normalize for the “token budget”—the actual computational cost of generating an answer—the landscape of LLM reasoning changes dramatically.

In this post, we will deconstruct this paper to understand why simple methods like Chain-of-Thought with Self-Consistency might actually be the most efficient “smart” strategies we have, and why complex multi-agent systems often fail to justify their high costs.

Background: The Zoo of Reasoning Strategies

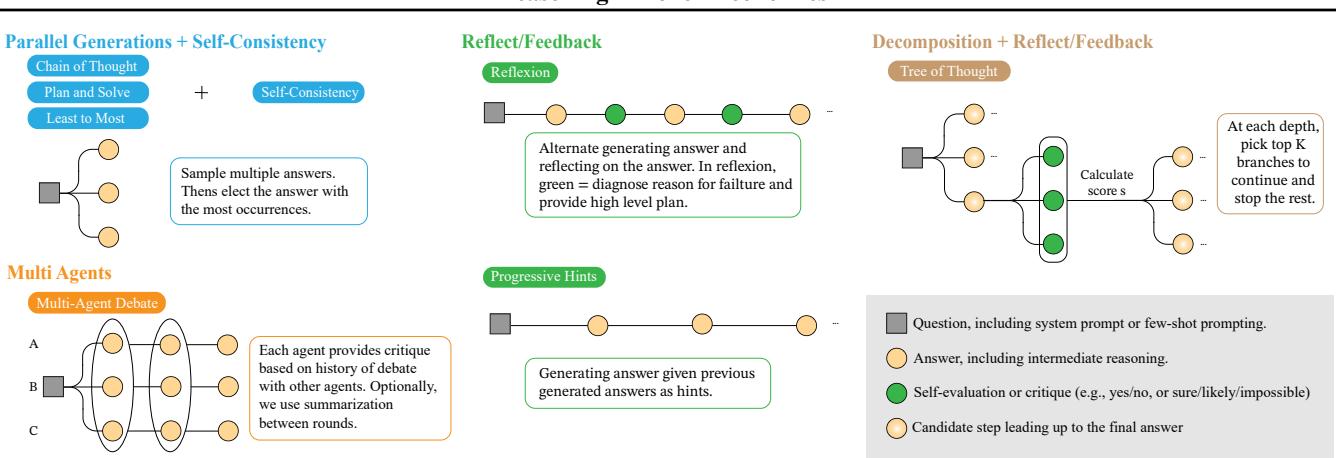

Before diving into the budget wars, we need to understand the combatants. The field of Prompt Engineering has evolved into “Inference-Time Reasoning Strategies.” Here are the key players discussed in this analysis:

1. Chain-of-Thought (CoT) & Self-Consistency (SC)

The most famous advanced prompting technique is Chain-of-Thought (CoT). Instead of asking for an answer, you ask the model to “think step-by-step.” Self-Consistency (SC) takes this a step further. You run the CoT prompt multiple times (sampling) to generate diverse reasoning paths and answers. Then, you take a majority vote. If 7 out of 10 paths lead to the answer “42,” the model outputs “42.”

2. Complex Strategies

Researchers have tried to engineer more human-like reasoning processes:

- Multi-Agent Debate (MAD): Multiple LLM instances (“agents”) propose answers, critique each other, and iterate over several rounds to reach a consensus.

- Reflexion: The model generates an answer, critiques its own output to find errors, and then tries again based on that feedback.

- Tree of Thoughts (ToT): The model explores a search tree of possibilities. It generates multiple next steps, evaluates them, and keeps only the promising branches, similar to how a chess engine looks ahead.

As shown in Figure 2, these strategies differ significantly in complexity. CoT is linear. Reflexion involves loops. Tree of Thoughts involves branching. Naturally, the methods on the right side of the diagram consume significantly more tokens and API calls than a single prompt.

The Core Problem: The “Scale-Agnostic” Illusion

The central thesis of the paper is that comparing these strategies without looking at the cost is unfair.

In a “scale-agnostic” evaluation (the standard method), a researcher might compare Single-Agent CoT against Multi-Agent Debate (3 rounds, 6 agents).

- The Single-Agent generates perhaps 500 tokens.

- The Multi-Agent Debate might generate 10,000 tokens as agents talk back and forth.

If the Debate wins by 2%, it is declared the superior method. But what if we allowed the Single-Agent CoT to sample 20 times (Self-Consistency) so that it also used 10,000 tokens? Who wins then?

Defining the Budget

The authors propose a Budget-Aware Evaluation Framework. They measure budget in two ways:

- Number of Queries: How many times do we call the API? (Important for latency and rate limits).

- Number of Tokens: The total sum of input and output tokens. (Important for financial cost and compute load).

When we view the leaderboard through this lens, the rankings flip.

Figure 1 above illustrates this phenomenon perfectly.

- Left (Scale-Agnostic): Multi-agent debate (orange star) seems to dominate Single-agent (gray square).

- Right (Scale-Aware): When we plot performance against the number of tokens (x-axis), the Multi-agent line (orange) and Reflexion line (green) are often below the simple CoT Self-Consistency line (blue).

This reveals that the “algorithmic ingenuity” of complex agents might actually just be the brute force of using more compute.

The Core Method: Investigating the Trade-off

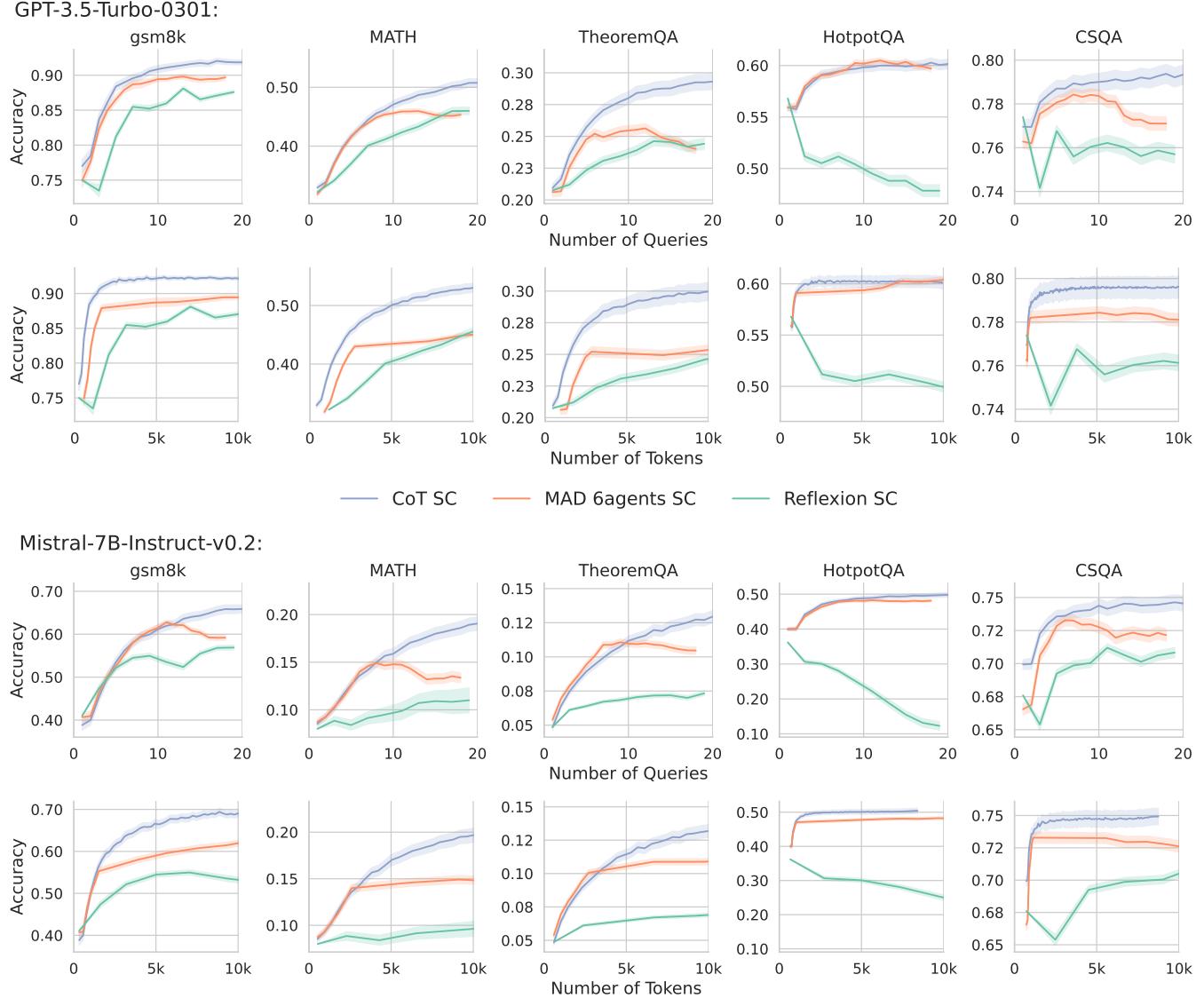

The researchers conducted an extensive evaluation across five distinct datasets, ranging from math problems (GSM8K, MATH) to commonsense reasoning (CSQA) and multi-hop QA (HotpotQA). They tested models like GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and open-source alternatives like Llama-2 and Mistral.

Their methodology was rigorous: strict budget matching. If a complex strategy like “Plan-and-Solve” used 5,000 tokens to answer a question, the baseline (CoT SC) was allowed to sample enough times to also utilize 5,000 tokens.

The Results: Simplicity Strikes Back

The results were consistent and somewhat surprising. Across almost all datasets, Chain-of-Thought with Self-Consistency (CoT SC) proved to be the most efficient strategy.

Take a look at Figure 3 above.

- The Blue Line (CoT SC): As you increase the budget (tokens/queries), accuracy climbs steadily.

- The Orange Line (MAD): In many cases, specifically in math datasets, it starts competitive but eventually plateaus or performs worse than the blue line.

- The Green Line (Reflexion): It often lags behind considerably.

The takeaway? If you have a budget of 3,000 tokens per question, you are usually better off sampling a simple CoT prompt 15 times and taking a majority vote than you are running a complex 3-round debate between agents.

Why Do Complex Strategies Falter?

It seems intuitive that “debate” or “reflection” should yield better answers. Why does simple voting beat them? The authors investigate the theoretical mechanisms behind this.

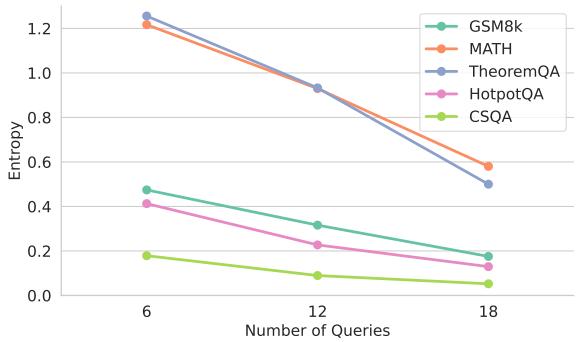

1. The Diversity Problem in Debates

In Multi-Agent Debate (MAD), agents see each other’s responses. This creates a dependency. If Agent A hallucinates a wrong answer confidently, Agent B might be swayed to agree. As the debate rounds continue, the “diversity” of the pool decreases. They all converge, but they might converge on the wrong answer.

Figure 6 shows the entropy (a measure of diversity) of the answers dropping drastically as the debate rounds progress (from query 6 to 18). Self-Consistency, by contrast, keeps every sample independent. Independence is crucial for the “Wisdom of the Crowds” effect—errors cancel out only if they aren’t correlated.

2. The Math Behind Self-Consistency

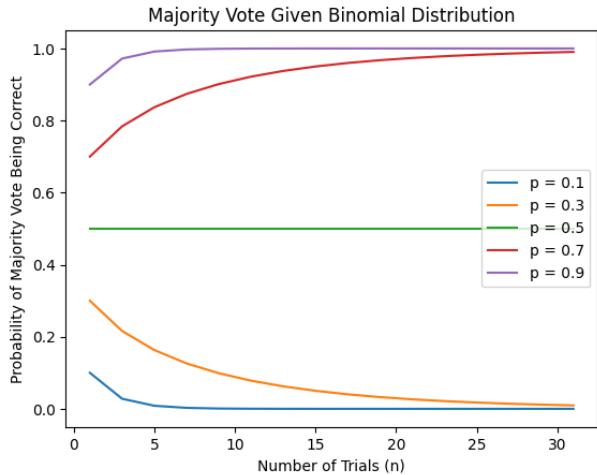

The authors provide a mathematical framework to explain why Self-Consistency (SC) scales so well. They model the probability of a correct majority vote using binomial and Dirichlet distributions.

As shown in Figure 12 (part of the image above), if the model has a greater than 50% chance of being right on a single try (\(p > 0.5\)), the probability of the majority vote being correct (\(P(\text{MV correct})\)) converges to 100% as you add more samples (\(N\)).

Essentially, SC turns a “decent” model into a “great” model purely through the statistics of independent sampling. Complex strategies introduce dependencies that break this mathematical guarantee.

The “Tree” and The “Evaluator”

The paper also dedicates specific attention to Tree of Thoughts (ToT) and the concept of Self-Evaluation, which is critical for strategies like Reflexion.

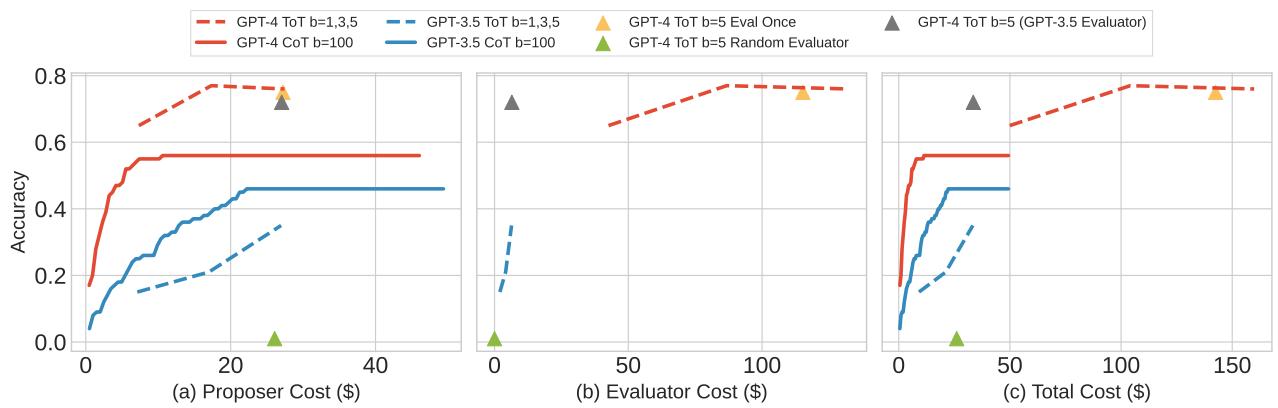

Tree of Thoughts: Expensive but Effective?

Tree of Thoughts (ToT) was one of the few strategies that showed promise against the baseline, particularly on hard tasks like the “Game of 24” (a math puzzle). However, ToT requires two components:

- Proposer: Generates next steps.

- Evaluator: Scores those steps.

The authors found that ToT is incredibly expensive. Furthermore, it relies heavily on the strength of the model.

In Figure 8, we see the cost (in dollars) vs. accuracy. ToT (the dashed/dotted lines) can achieve higher accuracy than CoT (solid lines), but look at the cost on the X-axis. To get that boost, you might be paying 10x or 20x more per question. For many applications, this diminishing return isn’t viable.

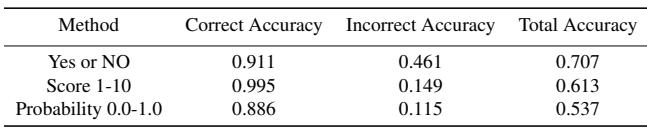

The Weakness of Self-Evaluation

Strategies like Reflexion and ToT rely on the LLM’s ability to look at its own work and say, “This is wrong.”

The researchers tested this “Self-Evaluation” capability and found it lacking. They compared different ways of asking the model to evaluate itself (Yes/No, 1-10 scores, probabilities).

Figure 15 (top of the image above) reveals a calibration problem. Ideally, if a model is 80% confident (x-axis), it should be correct 80% of the time (y-axis). The curves show significant deviation.

- Table 2 highlights that on the MATH dataset, the “Incorrect Accuracy” is low. This means when the model is wrong, it often fails to realize it.

If an LLM cannot accurately detect its own errors, strategies like Reflexion become “blind”—they iterate on the answer but don’t necessarily improve it.

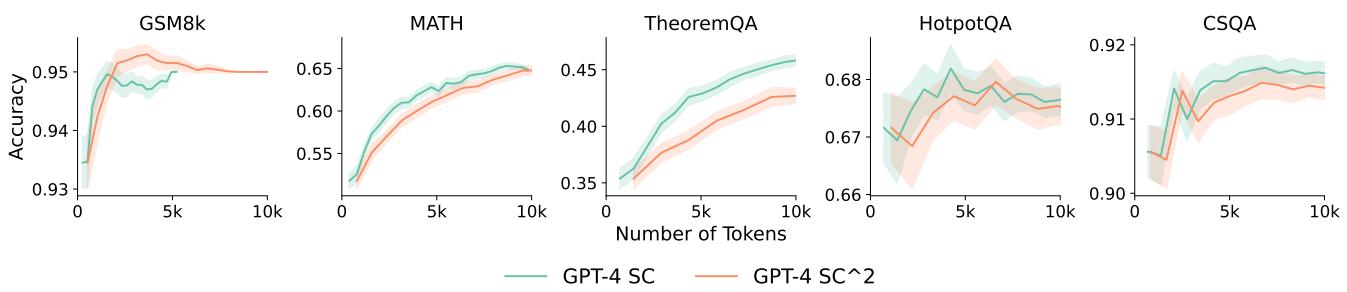

A New Hope: Self-Confident Self-Consistency (\(SC^2\))

Despite the poor calibration, the authors found a way to squeeze value out of self-evaluation. They proposed \(SC^2\) (Self-Confident Self-Consistency).

Instead of a simple majority vote (1 person = 1 vote), they weighted the votes by the model’s confidence in that answer. Even though the calibration isn’t perfect, it provides enough signal to filter out very low-confidence hallucinations.

As Figure 16 demonstrates, \(SC^2\) (orange line) outperforms standard SC (green line) on math datasets (GSM8K, MATH). This suggests that while complex reflexive loops might fail, simply asking the model “Are you sure?” and using that to weight the vote is a budget-efficient improvement.

Conclusion: Implications for AI Development

This paper serves as a reality check for the AI community. It shifts the focus from “novel architectures” back to the fundamentals of probability and compute efficiency.

Key Takeaways for Students and Practitioners:

- Count the Tokens: Never judge a reasoning strategy by accuracy alone. Always ask: “What is the cost?”

- The Baseline is Hard to Beat: Simple Chain-of-Thought with Self-Consistency is an incredibly robust baseline. If a new paper claims to beat it, check if they matched the compute budget.

- Independence Matters: When designing multi-agent systems, beware of “groupthink.” Independent sampling (SC) often beats collaborative debate because errors remain uncorrelated.

- Self-Correction is Hard: Don’t assume an LLM can fix its own mistakes. Current models are often overconfident and poor at self-diagnosis.

As we move forward, the “Token Economy” will dictate deployment. Theoretical improvements are exciting, but in the real world, the strategy that delivers the best answer per dollar (or per GPU-second) will win. Right now, that winner is often the simple, statistically sound approach of asking the model to “think step-by-step” and taking the majority vote.

Comparison of Equations

For the mathematically inclined, the paper grounds the success of Self-Consistency in the convergence of the binomial distribution.

The probability of a single sample being correct is modeled as a Bernoulli trial. The probability of the Majority Vote (MV) being correct is the sum of the probabilities of obtaining at least \(n/2\) correct votes:

\[ P ( { \mathrm { M V ~ c o r r e c t } } | x _ { i } ) = \sum _ { k = \lceil n / 2 \rceil } ^ { n } { \binom { n } { k } } p _ { i } ^ { k } ( 1 - p _ { i } ) ^ { n - k } . \]As \(n\) (budget) approaches infinity, this function acts as a sigmoid, pushing the accuracy to 100% as long as the base accuracy \(p_i\) is above 0.5:

\[ \operatorname* { l i m } _ { n \infty } P ( \mathrm { M V } \mathrm { c o r r e c t } | x _ { i } ) = \{ { 1 \atop 0 } \mathrm { ~ i f ~ } p _ { i } > 0 . 5 , \]This mathematical certainty explains why throwing compute at independent samples (SC) is so effective compared to complex, dependent chains where errors can compound.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.06461/images/cover.png)