Introduction

Climate change is arguably the most pressing challenge of our time. To understand how the corporate world is adapting, stakeholders—from investors to regulators—rely heavily on corporate sustainability reports. These documents are massive, qualitative, and complex, often hiding crucial data regarding climate risks and strategies within dense textual narratives.

To process this flood of information, the tech world has turned to Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG). RAG systems use Artificial Intelligence to search through documents, find relevant paragraphs, and use them to generate answers to specific questions. It sounds like the perfect solution. However, there is a catch: we don’t actually know how good these systems are at the specific task of retrieval in the climate domain.

If a RAG system fails to find the correct paragraph (retrieval), the AI cannot generate a correct answer (generation), leading to hallucinations. While we have ways to check if the generated text reads well, we have lacked a solid benchmark to verify if the AI found the right evidence in the first place.

Enter ClimRetrieve. In a recent paper, researchers introduced a new benchmarking dataset designed to simulate the workflow of a professional sustainability analyst. By creating a gold-standard dataset of questions and verified sources, they have opened the door to understanding—and improving—how AI interacts with complex climate data.

Background: The Complexity of Climate NLP

Before diving into the dataset, it is important to understand why this is hard. Natural Language Processing (NLP) in the climate space has historically focused on classification—for example, detecting “greenwashing” or categorizing a statement as “environmental” or “social.”

However, modern analysis requires more than just categorization; it requires complex reasoning. Consider the question: “Does the company have a specific process in place to identify risks arising from climate change?”

To answer this, an analyst (or an AI) cannot simply look for the keyword “risk.” They must understand concepts like “physical risk,” “transition risk,” “adaptation,” and “governance.” They need to differentiate between a general statement about caring for the planet and a specific, actionable process.

RAG systems attempt to solve this by embedding both the question and the document text into mathematical vectors. If the vector of the question is “close” to the vector of a paragraph, the system assumes that paragraph contains the answer. But does this standard approach capture the nuance of expert climate knowledge? That is exactly what ClimRetrieve aims to test.

Building the ClimRetrieve Dataset

The core contribution of this research is the creation of a dataset that mimics expert human behavior. The researchers did not simply scrape data; they employed a rigorous, expert-led process.

The Analyst Workflow

The dataset is built around 30 sustainability reports and 16 detailed questions focused on climate change adaptation and resilience. These questions were not random; they were inspired by frameworks designed to align finance with adaptation goals.

The creation process involved three expert annotators (researchers with backgrounds in climate science) who followed a specific workflow to ensure high-quality data.

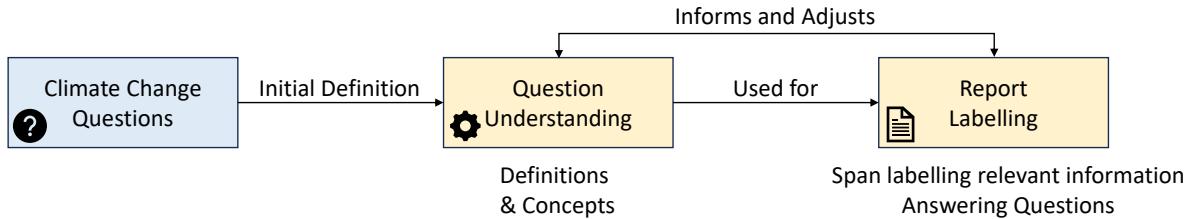

As shown in Figure 2, the process was iterative:

- Question Understanding: Before looking at the reports, the experts defined the questions and the underlying concepts.

- Report Labeling: They read the reports to find specific spans of text that answered the questions.

- Refinement: The definitions were constantly adjusted based on what was found in the real-world reports.

This process resulted in a dataset of over 8,500 labeled paragraphs. Each entry contains the document, the question, the specific text source, and—crucially—a relevance score.

Not All Relevance is Equal

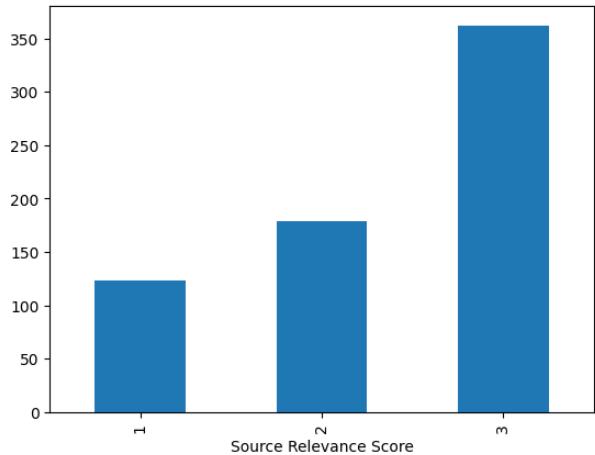

In the real world, an answer isn’t always a simple “yes” or “no.” Sometimes a paragraph is crucial (Relevance 3), and sometimes it is only tangentially related (Relevance 1).

Figure F.1 illustrates the distribution of these labels in the final dataset. The researchers found that the majority of sources identified by experts were highly relevant (score 3). This reflects the analyst’s mindset: they are looking for the best possible evidence to support their conclusions.

The final result is a “Report-Level Dataset.” For every paragraph in a report, we now know whether it is relevant to a specific climate question or not. This effectively creates a “ground truth” that we can use to test AI models.

The Experiment: Can AI Search Like an Expert?

With the dataset in hand, the researchers posed a critical question: How can we integrate expert knowledge into the retrieval process?

In a standard RAG setup, the system takes a user’s question, turns it into a vector, and searches for similar vectors in the document. But climate questions are “knowledge-intensive.” A simple semantic search might miss the deeper conceptual links an expert would naturally make.

The researchers designed an experiment to test different search strategies using “Embedding Models” (the AI that turns text into numbers). They compared four main approaches to searching for answers:

- Question Only: The standard approach. Just embed the question.

- Definitions & Concepts: Replacing the question with the definitions written by the human labelers.

- Generic Explanations: Asking GPT-4 to write an explanation of what the question means and using that for the search.

- Expert-Informed Explanations: The most advanced method. Here, they provided GPT-4 with actual examples of relevant paragraphs (from the training set) and asked it to write a search query based on those examples.

Engineering the Perfect Prompt

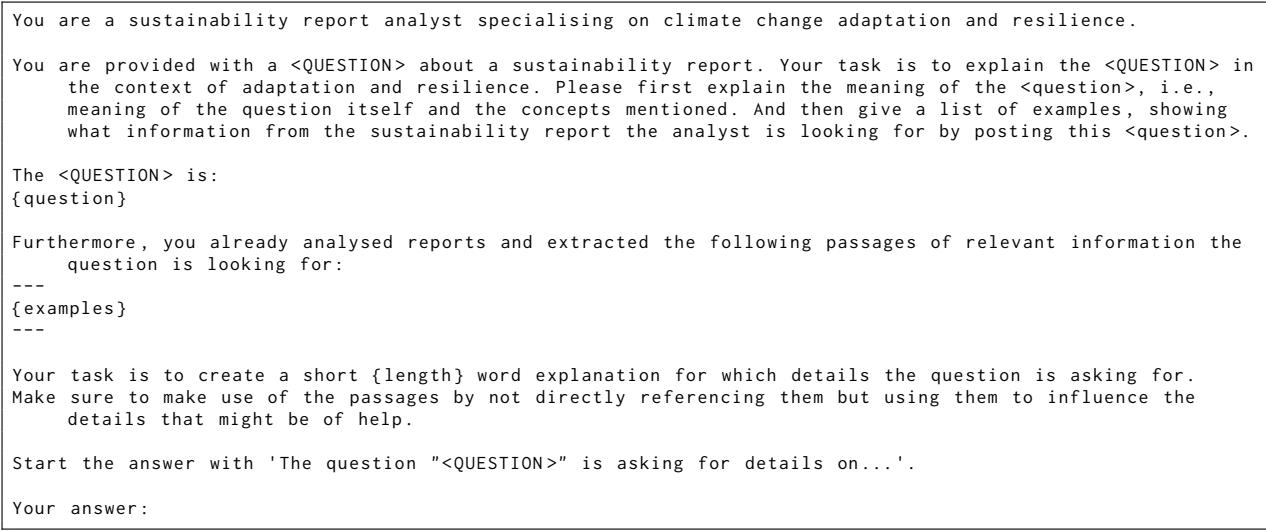

To generate these “Expert-Informed Explanations,” the researchers used specific prompts that leaked a bit of “gold standard” knowledge into the query generation process to simulate an expert’s intuition.

Figure H.5 shows how they prompted the model. They provided the question and examples of relevant passages, then asked the model to explain what details an analyst is looking for.

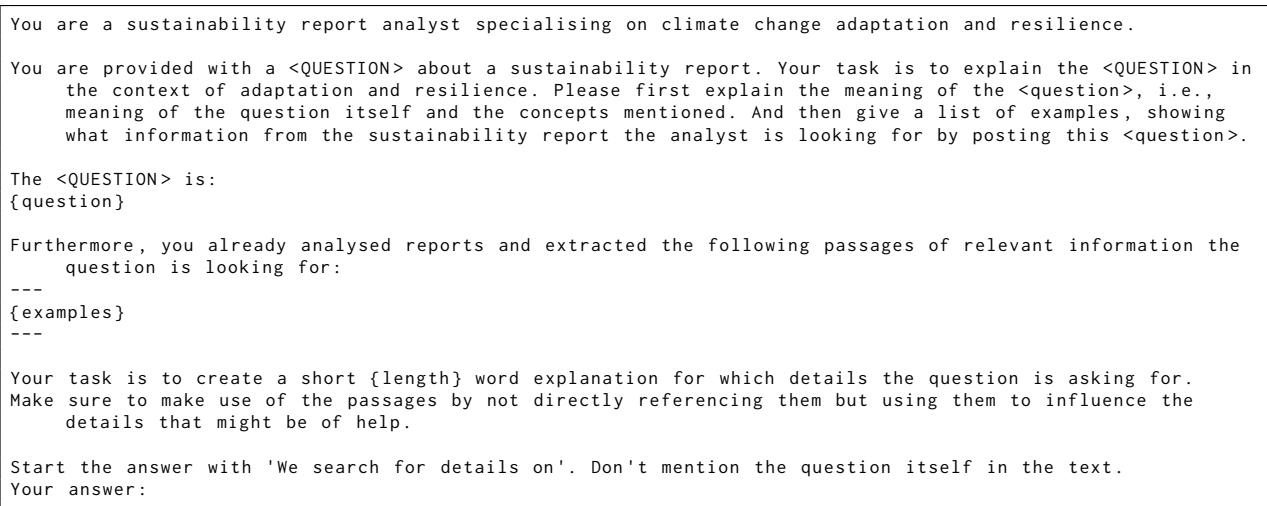

They also tested a variation where they explicitly excluded the question text from the search query, relying only on the explanation.

As seen in Figure H.6, this prompt forces the search to focus entirely on the concepts and details required, rather than the phrasing of the original question.

Experiments & Results

To evaluate which method worked best, the researchers used standard information retrieval metrics: Recall@K and Precision@K.

Recall@K measures how many of the relevant paragraphs the system found within its top K results (e.g., the top 5 or top 10 paragraphs).

Precision@K measures how many of the retrieved paragraphs were actually relevant.

The Findings

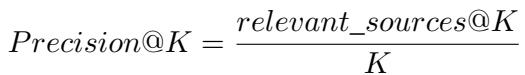

The results were surprising and highlighted the limitations of current “out-of-the-box” AI models.

1. Human Definitions didn’t help. Counter-intuitively, replacing the question with the definitions written by the human annotators actually decreased performance compared to just using the question. The researchers hypothesize that this is because human notes are written to aid human understanding, not to be optimized for vector search algorithms.

2. Expert-Informed Explanations are superior. The experiment showed that using “Expert-Informed Explanations”—queries generated by an LLM that had seen examples of correct answers—significantly outperformed other methods.

Figure 3 presents the results using the text-embedding-3-large model. The X-axis represents the different strategies (question, generic, inf_3, inf_all).

- Recall (Top row): Notice the upward trend. The

inf_allstrategy (using explanations informed by all available examples) consistently retrieves more relevant sources than the simplequestionstrategy. - Precision (Bottom row): Precision tends to drop as we retrieve more documents (higher K), which is expected. However, the expert-informed strategies still maintain a competitive edge.

3. The “No Question” Strategy.

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that the best performance often came from excluding the question itself from the search query (the noQ lines in the graphs). By searching solely with the detailed explanation of what is needed (concepts, specific data points), the embedding model was less distracted by the phrasing of the question and focused more on the semantic content of the answer.

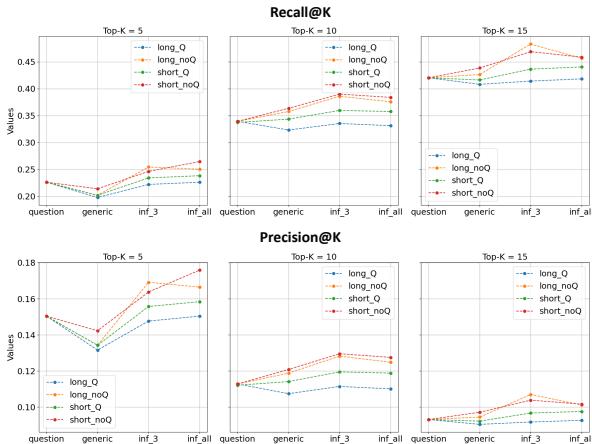

Robustness of Results

The researchers verified these findings across multiple embedding models, including text-embedding-3-small.

As shown in Figure L.10, even with a smaller, less powerful model, the trend holds: informing the search with expert-level explanations (the right side of the charts) yields better recall than using the question alone.

Conclusion and Implications

The ClimRetrieve paper highlights a critical gap in the current deployment of AI in sustainability. While RAG systems are powerful, they are not magic. In knowledge-intensive domains like climate change, simply plugging a question into a standard embedding model is often insufficient to capture the nuance required for accurate reporting.

The key takeaways from this work are:

- Domain Expertise Matters: Standard “State of the Art” embedding models struggle to reflect domain expertise on their own.

- Prompt Engineering for Retrieval: We can improve performance by transforming user questions into detailed, example-informed explanations before performing a search.

- The Dataset: ClimRetrieve provides the necessary benchmark for researchers to test and improve future RAG systems dedicated to climate disclosures.

For students and future researchers, this paper serves as a reminder that “better AI” isn’t always about a bigger model; sometimes, it is about better data and a deeper understanding of the domain you are trying to solve. By simulating the human expert’s workflow, we can build systems that don’t just read words, but actually understand the concepts behind them.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.09818/images/cover.png)