Introduction: The Hotpot Dilemma

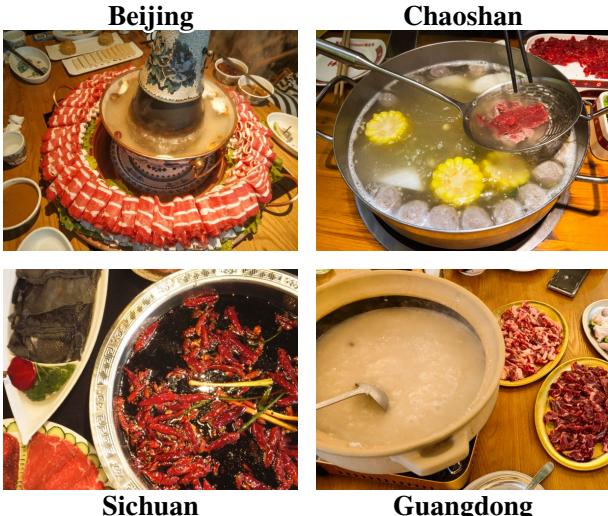

Imagine walking into a restaurant in Beijing. You order “hotpot.” You receive a copper pot with plain water and ginger, accompanied by thinly sliced mutton and sesame dipping sauce. Now, imagine doing the same thing in Chongqing. You receive a bubbling cauldron of beef tallow, packed with chili peppers and numbing peppercorns, served with duck intestines. Same name, entirely different cultural experiences.

For humans, these distinctions are part of our cultural fabric. We understand that food isn’t just a collection of ingredients; it is tied to geography, history, and local tradition. But for Artificial Intelligence, specifically Vision-Language Models (VLMs), this level of fine-grained cultural understanding is a massive blind spot.

While modern AI can easily identify a “pizza” or a “burger,” it often struggles with the intricate regional diversity within a specific cuisine. To address this, researchers have introduced FoodieQA, a dataset designed to test the limits of AI’s understanding of Chinese food culture.

As illustrated in Figure 1, “hotpot” varies wildly across China. From the milky broths of Guangdong to the fiery oils of Sichuan, these visual cues tell a story of regional identity. FoodieQA asks a critical question: Can state-of-the-art AI models read these cues, or are they culturally illiterate?

The Gap in Culinary AI

Before diving into the methodology of FoodieQA, it is essential to understand why this dataset was necessary.

Previous datasets in the food domain have primarily focused on two things:

- Food Recognition: “Is this a hot dog or a salad?” (e.g., Food-101).

- Recipe Generation: “How do I cook this dish?” (e.g., Recipe1M).

However, these datasets often take a coarse view of culture. They might label a dish simply as “Chinese” or “Italian,” ignoring the fact that cuisine varies from village to village, let alone province to province. They often conflate country of origin with culture. Furthermore, most existing benchmarks rely on images scraped from the public web. This leads to a problem known as “data contamination”—since models like GPT-4 are trained on the internet, they have likely already “seen” the test images, making evaluations unfair.

FoodieQA bridges this gap by focusing on fine-grained regional diversity and ensuring data integrity through a unique collection process.

Constructing FoodieQA: A Cultural Deep Dive

The researchers behind FoodieQA didn’t just scrape Google Images. They built a dataset from the ground up to ensure it truly represented the lived experience of Chinese dining.

1. Expanding the Map

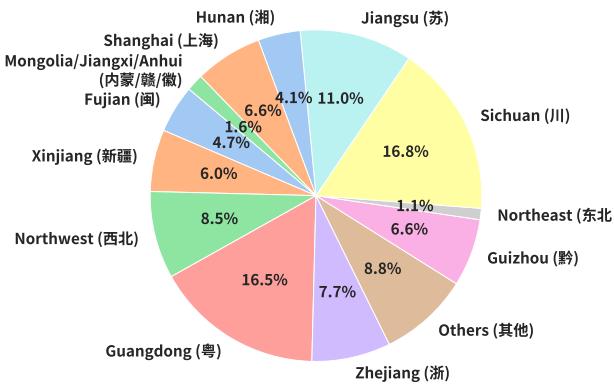

The traditional view of Chinese cuisine often centers on the “Eight Major Cuisines” (e.g., Sichuan, Cantonese, Shandong). FoodieQA expands this to 14 distinct cuisine types to ensure better geographical coverage, including cuisines from Xinjiang, the Northwest, and Mongolia.

As shown in Figure 3, the dataset covers a vast area, requiring models to distinguish between the heavy, wheat-based diets of the North and the rice-and-seafood-heavy diets of the South.

2. The “Freshness” of Data

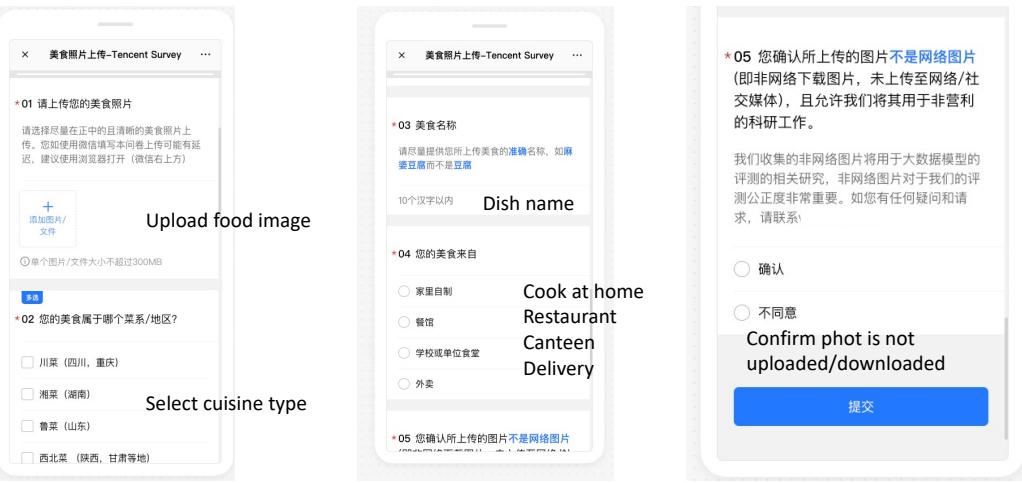

One of the most innovative aspects of FoodieQA is its image sourcing. To prevent models from cheating (by recalling images they saw during training), the researchers crowd-sourced images directly from locals.

Participants were asked to upload photos from their own camera rolls—images that had never been posted to social media or the public web. This ensures that when a model looks at a FoodieQA image, it is seeing it for the very first time.

Figure 11 shows the interface used for this collection. Contributors had to verify the cuisine type, dish name, and origin (home-cooked, restaurant, etc.), ensuring high-quality, authentic metadata.

3. The Three Tasks

To rigorously test the models, the researchers designed three distinct tasks, ranging from visual recognition to complex reasoning.

Figure 2 provides a clear breakdown of these tasks:

- Multi-Image VQA (The Menu Test): This is perhaps the most challenging task. The model is presented with four images (like looking at a menu with photos) and asked a question like, “Which is a cold dish in Sichuan cuisine?” The model must compare visual features across multiple images to find the answer.

- Single-Image VQA: The model is shown one image and asked fine-grained questions about it, such as “Which region is this food a specialty of?” Importantly, the dish name is often withheld, forcing the model to rely on visual cues rather than text priors.

- Text QA: A text-only test to evaluate the model’s encyclopedic knowledge of food culture (e.g., “What is the flavor profile of White-Cut Chicken?”).

4. Fine-Grained Annotation

To create these questions, native speakers annotated the images with detailed metadata. They didn’t just name the dish; they described its flavor profile (salty, spicy, sour), ingredients, cooking skills (steaming, braising), and serving temperature.

Figure 4 illustrates this depth. For a dish like “Meigancai with Pork,” the annotation captures details like “served in a bowl,” “soy-sauce color,” and “Hakka region.” This allows for questions that go beyond simple identification, probing deep cultural knowledge.

The Experiments: How “Foodie” are the Models?

The researchers benchmarked a wide range of models, including open-weights models (like Llama-3, Qwen-VL, Phi-3) and proprietary closed-weights models (GPT-4V, GPT-4o). The results revealed a significant gap between human understanding and AI capability.

The Multi-Image Challenge

The “Menu Test” (Multi-Image VQA) proved to be exceptionally difficult for AI.

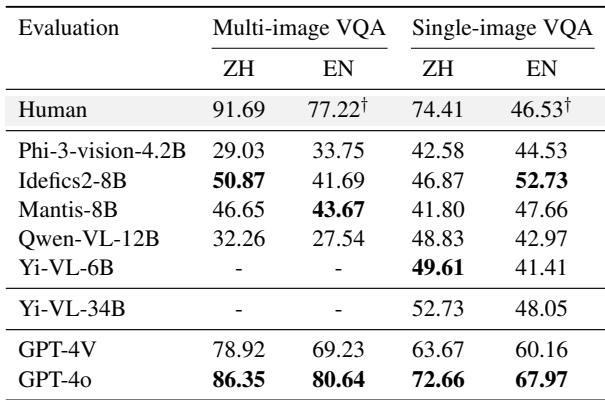

As seen in Figure 6, human accuracy on this task is high (91.69%). In contrast, the best open-weights model (Idefics2-8B) only achieved around 50.87%. Even the powerful GPT-4o, while closer, did not match human intuition.

This suggests that while models can process single images reasonably well, the ability to compare fine-grained visual details across multiple images to make a cultural deduction is still a major weakness.

Single-Image Performance & Language Bias

When the task was simplified to a single image, models performed better, but an interesting bias emerged regarding the language of the prompt.

Table 3 highlights a linguistic divide. Models that were bilingually trained (specifically on Chinese and English data, like Qwen-VL) performed significantly better when the questions were asked in Chinese. Conversely, some Western-centric models performed better in English, even when analyzing Chinese food. This indicates that a model’s cultural understanding is deeply tied to the language it is prompting in—a “cultural alignment” issue that developers need to address.

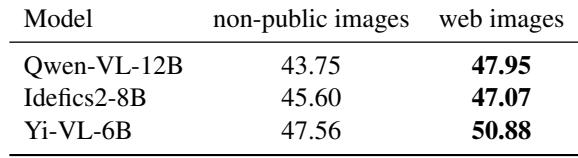

The Web-Image Trap

To prove the importance of their private image collection, the researchers ran a control experiment. They tested models on their private images versus images found on the web for the same dishes.

Table 4 confirms the hypothesis: models consistently scored higher on web images. This suggests “data contamination.” The models likely “remembered” the web images or similar compositions from their training data. By using private images, FoodieQA provides a much more honest assessment of a model’s actual reasoning capabilities.

Deep Dive Analysis: What Do Models Actually Know?

The study went further to analyze what specifically the models were getting wrong. Are they failing at identifying ingredients, or understanding the “vibe” of the food?

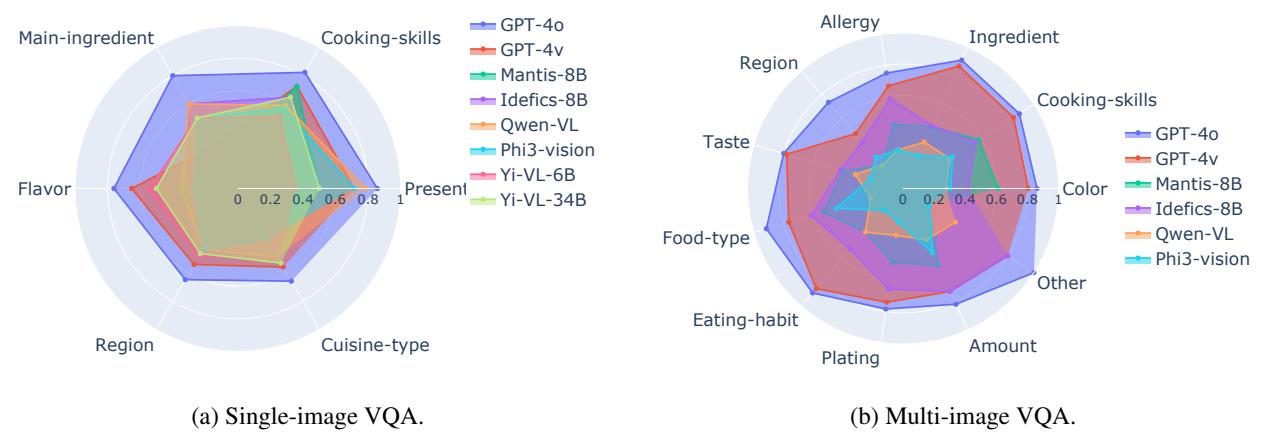

Cooking vs. Tasting

The researchers categorized questions by attribute (e.g., Cooking Skills, Flavor, Region).

The radar charts in Figure 8 tell a fascinating story.

- Strong Suits: Models are generally good at identifying ingredients and cooking skills. These are visual, objective facts (e.g., “I see a chili pepper,” “I see steam”).

- Weak Spots: Models struggle with Flavor and Region. These are cultural, subjective attributes. You cannot “see” saltiness, and you cannot necessarily “see” that a specific bowl shape implies the dish is from Jiangsu rather than Zhejiang without deep cultural context.

Models act like food scientists who know the chemistry but have never actually eaten the meal.

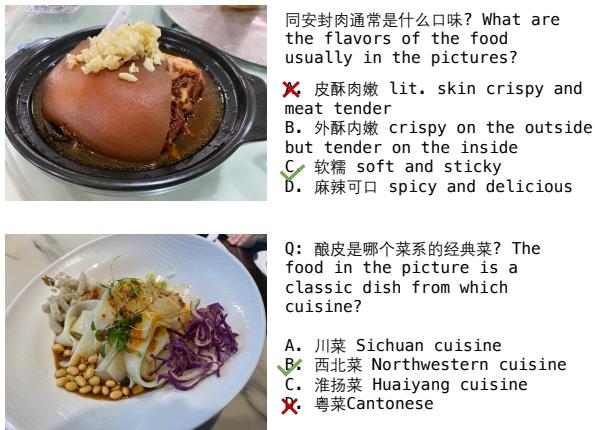

The Power of Visuals

Does seeing the food actually help, or are models just guessing based on text? The researchers compared model performance when given just the dish name versus the dish name plus the image.

Figure 15 (and quantitative data in the paper) shows that visual information is crucial. In the top example, the text asks about the flavor of “Tongan Fengrou.” Without the image, the model might guess. But seeing the glossy, dark skin of the pork and the specific clay pot helps the model correctly identify the “crispy skin, tender meat” texture profile.

However, this isn’t universal. For some models, adding the image actually confused them if the visual features were subtle, highlighting the instability of current multimodal systems.

Conclusion: The AI Palate Needs Refinement

The introduction of FoodieQA marks a significant step forward in evaluating Multimodal Large Language Models. It moves the goalpost from simple object recognition to cultural reasoning.

The key takeaways from this research are clear:

- The “Cliff” Exists: There is a 20-40% gap between human and AI performance in understanding regional food culture, particularly in multi-image scenarios.

- Data Purity Matters: Using private, unseen images is the only way to fairly evaluate these models.

- Culture is Nuanced: AI models grasp the “what” (ingredients) but miss the “where” and “why” (region and flavor).

As AI assistants become more integrated into our daily lives—potentially helping us order food, cook recipes, or navigate foreign countries—fine-grained cultural understanding will become a necessity. FoodieQA reveals that while AI might be able to read the menu, it’s not quite ready to recommend the local specialty in a small town in Sichuan.

The road to Artificial General Intelligence, it seems, goes through the stomach.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.11030/images/cover.png)