Imagine you are watching a movie, but instead of seeing the whole film, you are shown random, five-second clips in a shuffled order. In one clip, a character points to their left and laughs. In the next, they form a specific handshape and move it rapidly through the air.

If you were asked to translate exactly what those actions meant, could you do it? Likely not. Without knowing who is standing to the left, or what object was established in the scene prior, you are guessing.

This is essentially how we currently approach Sign Language Machine Translation (SLT). For years, researchers have treated sign language translation much like text-based translation: chopping continuous narratives into isolated “sentences” and asking models to translate them one by one.

In the paper “Reconsidering Sentence-Level Sign Language Translation,” researchers from Google and the Rochester Institute of Technology argue that this approach is fundamentally flawed. Through a novel human baseline study, they demonstrate that sign languages rely on discourse-level context—the information that came before—far more heavily than spoken languages do. Their findings suggest that by ignoring context, we aren’t just making the task harder; for about a third of all sentences, we are making it impossible.

The Problem with “Sentence-Level” Thinking

To understand the paper’s contribution, we first need to look at where the current standards come from. Much of the progress in Natural Language Processing (NLP) is built on text. In text translation (like Google Translate), processing sentences in isolation works reasonably well. If I say, “The cat sat on the mat,” you don’t necessarily need to read the previous page to translate that into French.

When researchers started tackling Sign Language Translation, they borrowed this “sentence-level” framework. They took videos of continuous signing (like news broadcasts or instructional videos), aligned them with the spoken transcript, and sliced the video into short clips corresponding to English sentences. Models were then trained to translate Clip A to Sentence A.

The authors of this paper argue that this inheritance was adopted uncritically. Sign languages are not just “spoken languages with hands.” They are visual-spatial languages with their own grammar, distinct from the spoken languages of their regions. The way signers establish meaning often spans across many sentences, creating dependencies that are severed when we chop the video into clips.

Why Sign Language Needs More Context

The researchers detail several specific linguistic phenomena in American Sign Language (ASL) that break down when you isolate a sentence. These are not edge cases; they are core grammatical features of the language.

1. Spatial Referencing and Pronouns

In English, we use pronouns like “he,” “she,” or “it.” If you hear “He went to the store” without context, you don’t know who “he” is, but you can still translate the grammar.

In ASL, pronouns are spatial. A signer will “set up” a person or object in a specific location in 3D space (a locus). Later in the conversation, they will simply point to that empty space or direct a verb toward it to reference that person.

If you slice the video, the “setup” might happen in Clip 1, but the “pointing” happens in Clip 5. A model (or a human) viewing Clip 5 in isolation sees a person pointing at empty air. Is that “John”? “Mary”? The “car”? Without the history, it is impossible to know.

2. Classifiers and Visual Iconicity

Sign languages make extensive use of classifiers. These are handshapes that represent categories of objects (like vehicles, flat objects, or cylindrical objects) and are moved through space to show action.

This is where the visual modality creates ambiguity that text doesn’t. A specific handshape might represent a vehicle in one context or a person’s legs in another.

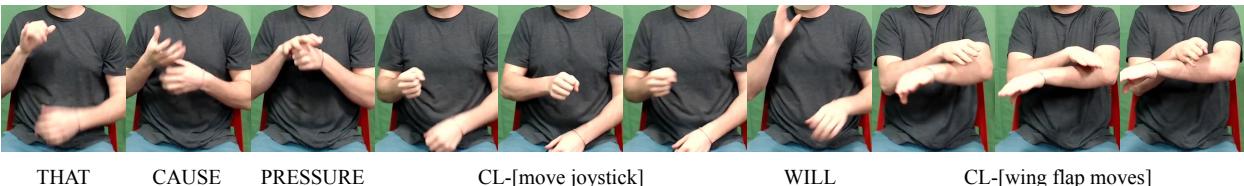

As shown in Figure 1 above, the signer is performing two actions. In the top row, they are moving a fist back and forth. In the bottom row, they are holding their arm flat with the hand flapping.

In isolation, the top gesture could be “driving,” “stirring,” or “holding a lever.” The bottom gesture could be a bird wing, a shelf, or a generic surface. However, the context of this specific video is a tutorial on flying an airplane. With that context, it becomes clear: the fist is controlling a joystick, and the arm represents the plane’s wing with the aileron moving. Without the previous sentences establishing the topic of “airplanes,” even a fluent signer might be baffled by these isolated clips.

3. Rapid Fingerspelling and “Abbreviated” Signs

When a signer introduces a new term (often a proper noun like a name or a technical term), they will usually fingerspell it clearly. This is analogous to writing a word out fully.

However, if they reference that word again later, they rarely spell it out clearly. They use rapid fingerspelling or “lexicalized” fingerspelling. The movements become blurred, effectively turning the spelling into a shape or a sign of its own.

Figure 2 illustrates this degradation. The top sequence shows the first time the signer spells “BASIL.” It is relatively clear. The bottom sequence shows a later mention. The letters are crushed together; the ‘B’ flows instantly into the ‘L’.

If you see the bottom clip in isolation, the shape is ambiguous. It could look like “BAIL,” “BILL,” or just a generic hand wave. But if you saw the clear spelling in the previous sentence, your brain essentially “autocompletes” the rapid version. Current sentence-level datasets deny models this ability to autocomplete.

The Case Study: A Human Baseline

Most AI papers propose a new model architecture. This paper takes a different approach: it establishes a human baseline. The logic is simple: if a fluent human signer cannot translate these clips without context, we shouldn’t expect an AI to do it either.

The researchers used the How2Sign dataset, a popular benchmark containing instructional videos (e.g., cooking, mechanics) translated from English to ASL. They recruited fluent Deaf signers to act as annotators.

The Experiment Setup

The annotators were asked to translate ASL clips into English under four progressive conditions. This allowed the researchers to measure exactly when the “understanding” clicked into place.

- Isolated Clip (\(s_i\)): The standard AI task. The translator sees only the current video clip.

- Extended Video (\(s_{i-1:i}\)): The translator sees the current clip and the previous clip.

- Extended Video + Text Context (\(s_{i-1:i}, t_{i-1}\)): The translator sees the previous clips and the ground-truth English text of the previous sentence.

- Full Context (\(s_{i-1:i}, t_{0:i-1}\)): The translator has access to the video history and the full English transcript up to that point.

Experiments & Results

The results were stark and highlighted a significant gap between how we score AI models and how translation actually works.

The “Impossible” 33%

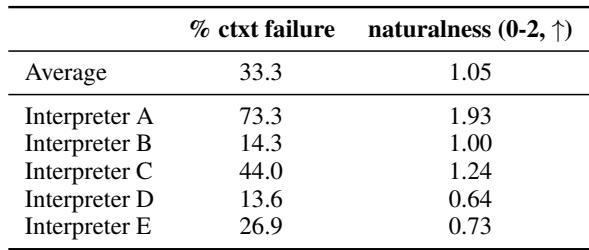

The most striking finding was qualitative. The Deaf annotators reported that 33.3% of the time, they were unable to fully understand the key details of a sentence in isolation, but could understand it once context was added.

This means that for one-third of the dataset, the “sentence-level” task is theoretically impossible. The information simply isn’t in the clip. It relies on a pronoun established 10 seconds ago, or a rapid fingerspelling of a word introduced 20 seconds ago.

Quantitative Scores

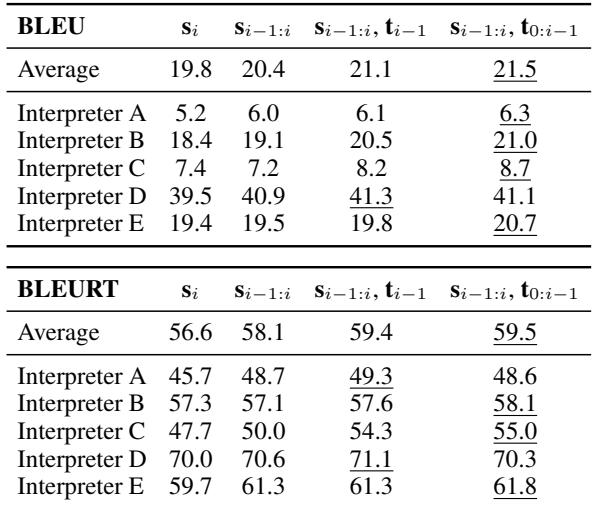

The researchers also measured the translations using BLEU and BLEURT (standard metrics for automated translation quality).

As seen in Table 1, the scores improve as context is added. The average BLEU score rises from 19.8 (isolated) to 21.5 (full context). While a 1.7 point increase might seem modest, in the world of machine translation, this is a meaningful margin. More importantly, these numbers correlate with the annotators’ subjective experience of “finally understanding” the clip.

The Interpreter “Trap”

One of the most fascinating aspects of this study was the analysis of who was signing. The How2Sign dataset uses different interpreters. The researchers found massive variation in performance depending on the specific interpreter.

Table 1 breaks this down by Interpreter (A through E). Look at the difference between Interpreter A and Interpreter D:

- Interpreter D: Scored a massive 39.5 BLEU on isolated sentences.

- Interpreter A: Scored a measly 5.2 BLEU on isolated sentences.

Does this mean Interpreter D is “better”? Surprisingly, no.

The researchers found that interpreters who scored highly on isolated sentences were often using Manually Coded English (MCE) or a very English-influenced signing style. They were essentially signing word-for-word, which is easier to translate back to English but is not natural ASL.

Conversely, Interpreter A was using deep, natural ASL grammar—using space, classifiers, and non-manual markers. This is “better” signing, but because it relies so heavily on ASL’s context-dependent grammar, it is much harder to translate in isolation.

Table 2 confirms this paradox. Interpreter A received the highest “Naturalness” rating (1.93 out of 2) but had the highest rate of context failure (73.3%). Interpreter D had the lowest naturalness rating (0.64) but rarely required context (13.6%).

This reveals a dangerous pitfall for AI researchers: If we optimize for sentence-level BLEU scores, we might inadvertently be training models to prefer unnatural, English-like signing over fluent, natural Sign Language.

Real-World Examples

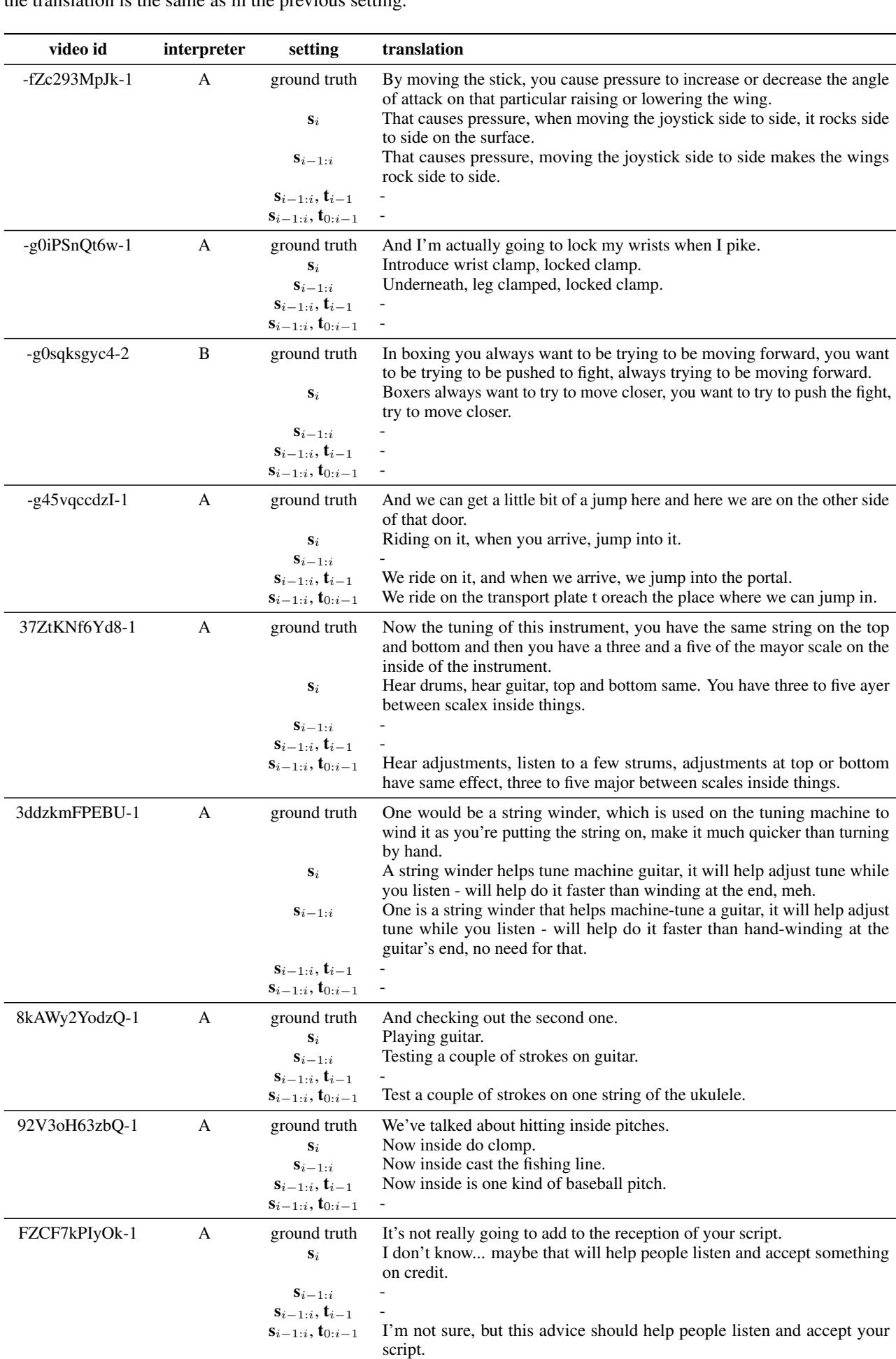

To make these abstract failures concrete, the paper provides transcripts of how the translations evolved as the humans received more context.

In Table 3, look at the first example (video id -fZc293MpJk-1).

- Isolated (\(s_i\)): The translator guesses about “causing pressure” and “angles.” It’s vague.

- With Context (\(s_{i-1:i}\)): The translation becomes specific: “moving the joystick side to side makes the wings rock side to side.”

The visual input didn’t change, but the meaning did. In the isolated clip, the “joystick” was just a fist moving. With context, the ambiguous handshape collapsed into a specific object.

Conclusion & Implications

The authors conclude that the field of Sign Language Translation must pivot. The convenience of sentence-level processing—borrowed from text NLP—is actively holding back progress in sign language processing.

The implications are threefold:

- Context is Non-Negotiable: Future datasets and models must be designed to handle document-level or discourse-level translation. We cannot chop videos into isolated sentences and expect high-quality results.

- Metric Misalignment: We need to be careful with our metrics. High BLEU scores on current datasets might just indicate that the data is “easy” (English-like) rather than correct (natural ASL).

- Human-in-the-Loop: This paper underscores the importance of sanity-checking AI tasks with humans. By simply sitting down and trying to do the task themselves, the researchers revealed a fundamental flaw that automated metrics missed for years.

For students and researchers entering this field, the message is clear: when working with Sign Language, you aren’t just processing language; you are processing a visual scene where history matters. To build systems that truly serve the Deaf community, we have to respect the linguistic reality of the language—context and all.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.11049/images/cover.png)