Why Fairer LLMs Make Better Judges: Inside the ZEPO Framework

If you have experimented with Large Language Models (LLMs) recently, you likely know that they are not just useful for writing code or generating poems—they are increasingly being used as evaluators. In a world where generating text is cheap but evaluating it is expensive, using an LLM to judge the quality of another LLM’s output (a technique often called “LLM-as-a-Judge”) has become a standard practice.

However, there is a significant catch. LLMs are notoriously fickle judges. Change the wording of your evaluation prompt slightly, and the model might completely flip its decision. They suffer from biases, such as preferring the first option presented to them or favoring longer, more verbose answers regardless of quality.

How do we fix this? How do we make LLM judges align better with human preferences without spending a fortune on labeled data?

A recent paper titled “Fairer Preferences Elicit Improved Human-Aligned Large Language Model Judgments” proposes a fascinating solution. The researchers discovered a strong link between fairness (statistical balance) and accuracy (human alignment). Based on this, they developed a framework called ZEPO (Zero-shot Evaluation-oriented Prompt Optimization).

In this deep dive, we will explore why LLM judges are biased, how “fairness” predicts performance, and how the ZEPO framework automatically optimizes prompts to create better AI evaluators.

The Problem: The Capricious Nature of LLM Judges

To understand the solution, we first have to understand the specific type of evaluation we are discussing: Pairwise Comparison.

Instead of asking an LLM to give a score from 1 to 10 (which is often arbitrary and inconsistent), researchers typically present two options—Candidate A and Candidate B—and ask the LLM: “Which summary is more coherent?”

While this method is generally more robust than direct scoring, it is plagued by prompt sensitivity. The specific instructions you give the model can drastically change the outcome.

Sensitivity and Bias

Imagine you have a dataset of 100 summarization tasks. You ask an LLM to judge them using Prompt X. The model might say it agrees with human annotators 40% of the time. Then, you rephrase the prompt slightly—keeping the meaning exactly the same—to create Prompt Y. Suddenly, the model agrees with humans 50% of the time.

This volatility is dangerous for research and production. If our evaluation metrics depend on lucky phrasing, we can’t trust them.

The researchers of this paper conducted a systematic study of this phenomenon. They took a set of instructions, paraphrased them into semantically equivalent variations, and tested how well the LLM’s judgments correlated with human judgments.

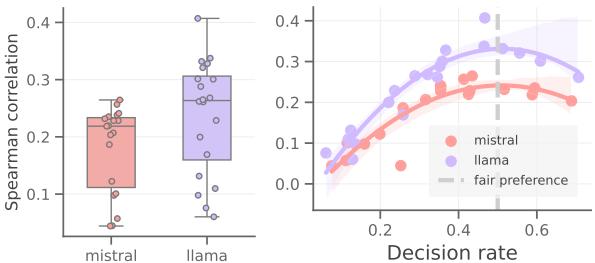

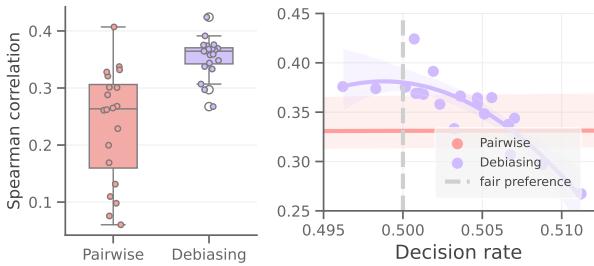

As shown in Figure 2 above, the results were striking.

- The Left Panel (Box Plot): Look at the spread for “Mistral” and “Llama.” The vertical axis represents the Spearman correlation with humans (higher is better). The huge variance in the box plots shows that simply paraphrasing the instruction can crash performance or boost it significantly.

- The Right Panel (Scatter Plot): This is the key insight of the paper. The x-axis represents the Decision Rate (the probability of choosing one class, like “Option A”, over the other). The y-axis is human alignment.

Notice the shape of the curve? It is a quadratic arch (an upside-down U).

- When the decision rate is extreme (e.g., 0.2 or 0.7), meaning the model is heavily biased toward choosing “A” or “B” almost all the time, the correlation with humans is low.

- The peak of human alignment happens right in the middle, around 0.5.

This leads to the paper’s core hypothesis: Fairer preferences (a balanced decision distribution close to 50/50) consistently lead to judgments that are better aligned with humans.

The Theoretical Pillar: Zero-Shot Fairness

Why does a 50/50 split matter?

By the law of large numbers, if you have a sufficiently large and diverse dataset of random pairwise comparisons, the “true” preference distribution should be roughly uniform. In other words, if you randomly pick pairs of summaries, “Summary A” should be better than “Summary B” about half the time, and vice versa.

If an LLM evaluator looks at a large dataset and decides that “Summary A” is better 80% of the time, it is likely suffering from preference bias. It isn’t judging the content; it’s relying on a spurious correlation (like the position of the answer or specific wording in the prompt).

Therefore, if we can force the model to have a “fair” (uniform) preference distribution, we are likely removing those biases and forcing the model to look at the actual content.

Introducing ZEPO: Zero-shot Evaluation-oriented Prompt Optimization

Motivated by the finding that fairness equals alignment, the authors proposed ZEPO.

ZEPO is an automatic framework that optimizes the prompt used for evaluation. Unlike other optimization methods that require thousands of human-labeled examples to “teach” the model what a good prompt looks like, ZEPO is zero-shot. It requires no labeled data.

It simply needs a pile of unlabeled inputs (e.g., source texts and pairs of summaries) and access to the LLM.

The Pipeline

Let’s break down how the ZEPO pipeline works, using the diagram provided in the paper.

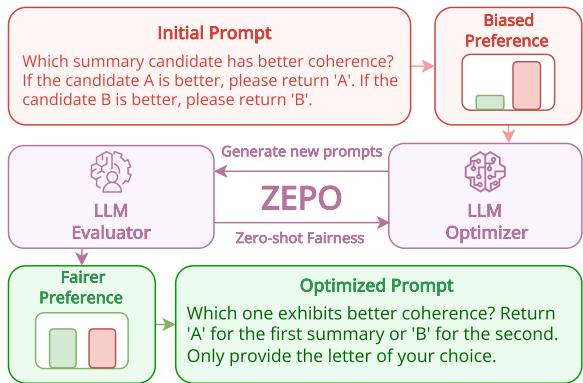

As illustrated in Figure 1:

- Initial Prompt: You start with a manual prompt (e.g., “Which summary is better?”).

- Biased Preference: The system runs this prompt over a sample of data. The bar chart shows a “Biased Preference,” where the red bar (Option B) is much higher than the green bar. The model is unfairly favoring one option.

- The Loop (ZEPO):

- LLM Optimizer: The system uses a separate LLM (like GPT-3.5 or GPT-4) to paraphrase the instruction. It generates variations of the prompt.

- LLM Evaluator: The target model (e.g., Llama-3) uses these new prompts to judge the data again.

- Fairness Calculation: The system calculates the “Fairness Score” for each new prompt. This score measures how close the decision distribution is to a perfect 50/50 split.

- Optimized Prompt: The loop continues until it finds a prompt that results in a “Fairer Preference” (equal height green and red bars). This prompt is selected as the winner.

The Algorithm Under the Hood

The process is iterative. Here is a simplified step-by-step of the algorithm used in the paper:

- Input: An initial instruction (e.g., “Evaluate coherence”).

- Generate Candidates: An optimizer LLM generates a batch of semantically equivalent prompts (paraphrases).

- Evaluate Fairness: For each candidate prompt, the evaluator LLM predicts preferences on a batch of unlabeled data.

- Calculate Metric: The system computes the fairness metric: \[ \text{Fairness} = - \sum | 0.5 - p(\text{prediction}) | \] Essentially, it penalizes the prompt if the prediction rate deviates from 0.5.

- Select Best: The prompt with the highest fairness score (closest to 0) becomes the seed for the next round of paraphrasing.

- Repeat: This runs for several epochs until convergence.

Why Fairness beats Confidence

You might wonder: “Why use fairness? Why not just ask the model to use the prompt it is most confident about?”

In machine learning, confidence (often measured by low entropy) is a common metric for selecting prompts. However, the researchers found that for LLM evaluators, confidence is a trap. An LLM can be extremely confident and extremely wrong (often called a hallucination or overconfidence bias).

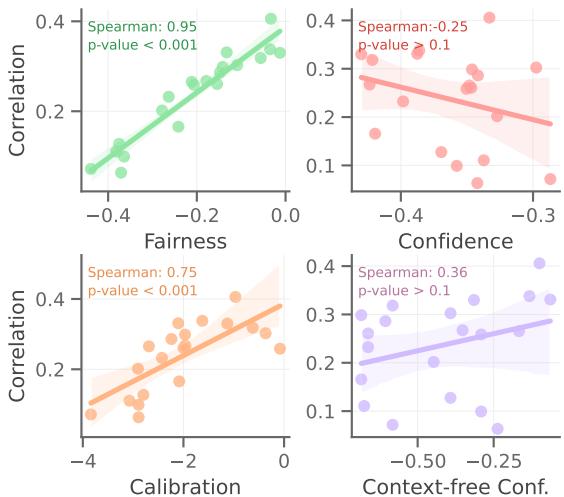

Figure 3 provides the statistical evidence for choosing fairness over other metrics:

- Top-Left (Fairness): The green trend line is steep and positive. The Spearman correlation is 0.95 (p-value < 0.001). This is a massive correlation. It confirms that as fairness improves (moves closer to 0 on the x-axis), the correlation with human judgment drastically improves.

- Top-Right (Confidence): The red line shows a negative correlation. Simply optimizing for model confidence actually hurt performance in this context.

- Bottom-Left (Calibration): Calibration (how well predicted probabilities map to accuracy) helps, but the correlation (0.75) is weaker than fairness.

This comparison validates the core premise of ZEPO: Fairness is the best proxy we have for human alignment when we don’t have ground-truth labels.

Experimental Results

So, does ZEPO actually deliver better judges? The authors tested the framework on representative benchmarks like SummEval and News Room (summarization tasks) and TopicalChat (dialogue).

They compared ZEPO against standard pairwise prompting and other baselines.

Summarization Benchmarks

Let’s look at the results for the “News Room” dataset.

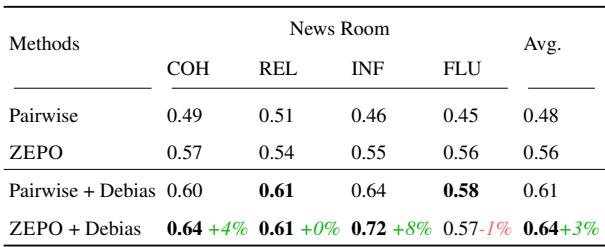

In Table 2, we see the Spearman correlations (agreement with humans) for different methods using the Llama-3 8B model:

- Pairwise (Baseline): 0.48 average correlation.

- ZEPO (Optimized): 0.56 average correlation.

That is a significant jump purely by changing the prompt automatically.

Furthermore, the table introduces the concept of Debiasing. A common technique to fix position bias is to run the evaluation twice (swap A and B) and average the results.

- Pairwise + Debias: 0.61.

- ZEPO + Debias: 0.64.

This tells us something crucial: ZEPO is orthogonal to debiasing. You don’t have to choose between optimizing the prompt and using debiasing techniques (like swapping positions). You can do both, and ZEPO still adds value.

We can visualize this “orthogonality” in Figure 4.

In the chart on the right, the Blue Dots (Debiasing) generally perform better than the Red Dots (Standard Pairwise). However, even within the blue dots, there is a curve. The debiased models still suffer from prompt sensitivity. By using ZEPO to find the prompt that lands at the peak of that blue curve (Decision Rate ~0.5), we extract the maximum possible performance.

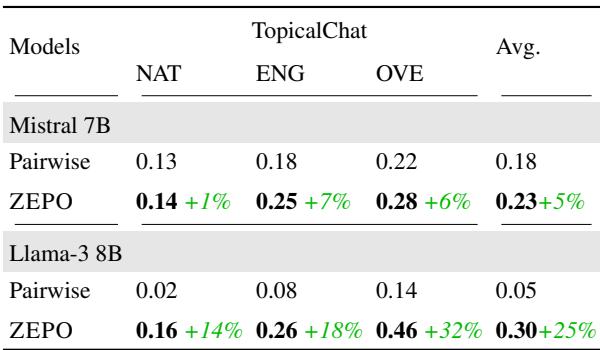

Dialogue Benchmarks

The effectiveness of ZEPO isn’t limited to summarization. The researchers also tested it on dialogue evaluation using the TopicalChat dataset.

Table 3 reveals massive improvements, particularly for Llama-3 8B:

- On Overall Quality (OVE), the correlation jumped from 0.14 (Pairwise) to 0.46 (ZEPO).

- That is a 32% improvement in alignment, transforming a barely usable evaluator into a moderately strong one.

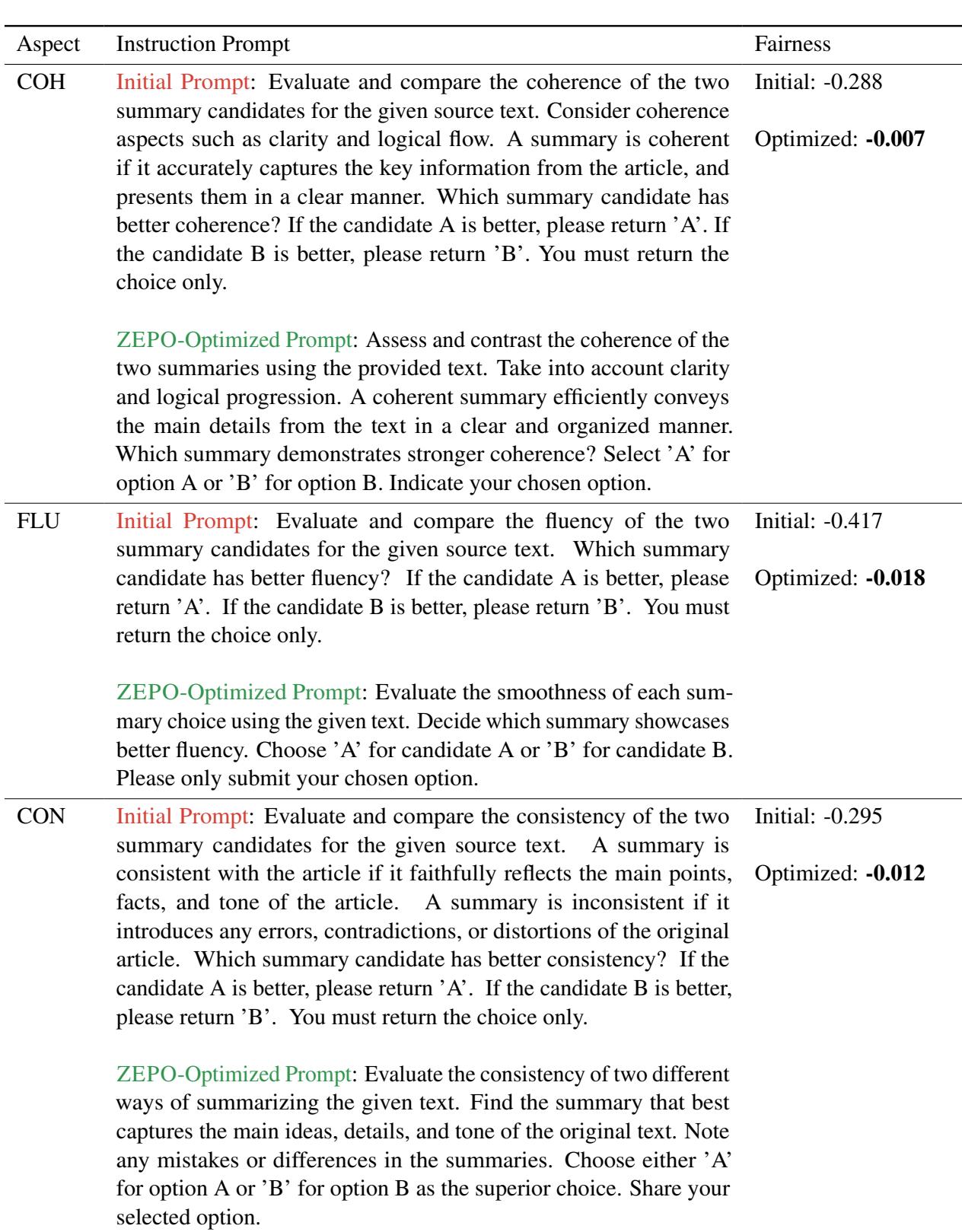

Qualitative Analysis: What does a “Fair” prompt look like?

It is easy to get lost in the numbers, but what is actually changing in the text? Does the optimizer write magic words?

Usually, the changes are subtle but impactful. The optimizer might clarify criteria, change the tone, or adjust the formatting constraints.

Table 5 provides concrete examples.

- Coherence (COH):

- Initial Prompt: “If the candidate A is better, please return ‘A’…” (Fairness: -0.288)

- ZEPO Prompt: “Select ‘A’ for option A or ‘B’ for option B…” (Fairness: -0.007)

- Result: The optimized prompt is much more direct and uses slightly different verbs (“Assess and contrast” vs “Evaluate and compare”). This tiny shift eliminated the bias.

- Fluency (FLU):

- Initial Prompt: Fairness -0.417 (Highly biased).

- ZEPO Prompt: Fairness -0.018 (Almost perfect).

- The optimized prompt focuses on “smoothness” and asks the model to “Evaluate the smoothness of each summary choice.”

This highlights that human intuition about what makes a “clear” prompt is often different from what an LLM perceives as a “neutral” prompt. ZEPO bridges that gap automatically.

Conclusion and Implications

The “LLM-as-a-Judge” paradigm is here to stay, but it requires safeguards. The paper “Fairer Preferences Elicit Improved Human-Aligned Large Language Model Judgments” provides a critical safeguard: the realization that a biased judge is a bad judge.

The key takeaways from this work are:

- Sensitivity is Real: Even powerful models like Llama-3 fluctuate wildly based on prompt wording.

- Fairness = Alignment: There is a nearly perfect correlation between statistical fairness (50/50 decision rates) and human alignment.

- ZEPO Works: We can automate the search for these fair prompts without needing any expensive human-labeled data.

For students and practitioners in NLP, this implies a shift in how we design evaluations. We cannot simply write a prompt once and trust it. We need to audit our prompts for statistical bias. If your model chooses “Option A” 90% of the time on a random dataset, you don’t just have a distribution problem—you have an accuracy problem.

ZEPO offers a path toward self-correcting, more reliable AI evaluators, bringing us one step closer to automated systems that truly understand human preferences.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.11370/images/cover.png)