Introduction

Imagine trying to explain the structure of an atom to someone who has never taken a physics class. You could recite a textbook definition about protons, neutrons, and electron shells. Or, you could say: “The atom is like a solar system. The nucleus is the sun in the center, and the electrons are planets orbiting around it.”

For most learners, the second explanation—the analogy—is the one that clicks. Analogical reasoning is a cornerstone of human cognition. It allows us to map the familiar (the solar system) onto the unfamiliar (the atom), building a bridge to new understanding.

In the world of Artificial Intelligence, researchers have long been fascinated by whether Large Language Models (LLMs) can generate analogies. We know they can complete patterns like “King is to Man as Queen is to Woman.” But a critical question remains: Are these AI-generated analogies actually useful? Can a “Teacher” model use an analogy to help a “Student” model understand a complex scientific concept?

This is the core question behind the research paper “Boosting Scientific Concepts Understanding: Can Analogy from Teacher Models Empower Student Models?” The researchers propose a new task called SCUA (Scientific Concept Understanding with Analogy) to test whether analogies are just linguistic distinctives or functional educational tools for AI.

The Problem with Current Analogy Research

Historically, AI research on analogies has focused on two things: identifying them and generating them. With the rise of massive models like GPT-4, we have moved from simple word associations to complex comparisons involving stories and processes.

However, the evaluation of these analogies has been somewhat superficial. Typically, a model generates an analogy, and human annotators grade it based on whether it makes sense. This overlooks the practical utility. In a classroom, a teacher doesn’t just make an analogy to sound poetic; they do it to help a student solve a problem. If the student still fails the test, the analogy wasn’t effective.

The authors of this paper argue that we need to align AI evaluation with this real-world educational scenario. We shouldn’t just ask, “Is this a good analogy?” We should ask, “Does this analogy help a student model answer a question it would otherwise get wrong?”

The SCUA Task: A Teacher-Student Framework

To investigate this, the researchers designed the SCUA task. This framework simulates a classroom environment involving two distinct types of AI agents:

- Teacher LMs: These are powerful, advanced models (like GPT-4 or Claude) capable of deep reasoning and high-quality generation.

- Student LMs: These are smaller or slightly weaker models (like Vicuna, Mistral-7B, or GPT-3.5) that are trying to answer difficult scientific questions.

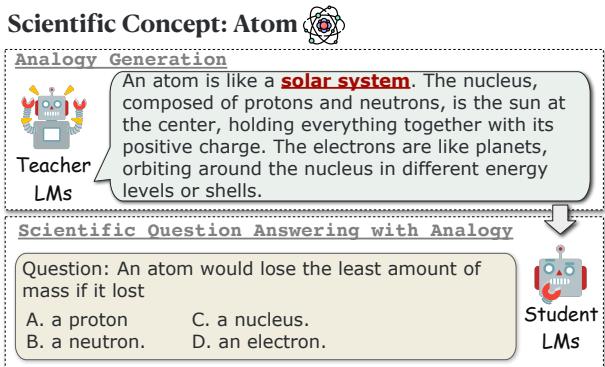

The process, illustrated below, is straightforward but rigorous.

As shown in Figure 1, the workflow begins with a scientific concept, such as “Atom.”

- The Teacher LM is prompted to generate an explanation using an analogy (e.g., comparing the atom to a solar system).

- The Student LM is presented with a difficult multiple-choice question related to that concept.

- The Student attempts to answer the question under two conditions: without the analogy and with the analogy provided by the Teacher.

By comparing the Student’s performance in both scenarios, researchers can quantify exactly how much “empowerment” the analogy provided.

Defining the Analogies

Not all analogies are created equal. A short metaphor is different from a paragraph-long explanation. To capture this nuance, the researchers instructed the Teacher LMs to generate three distinct types of analogies.

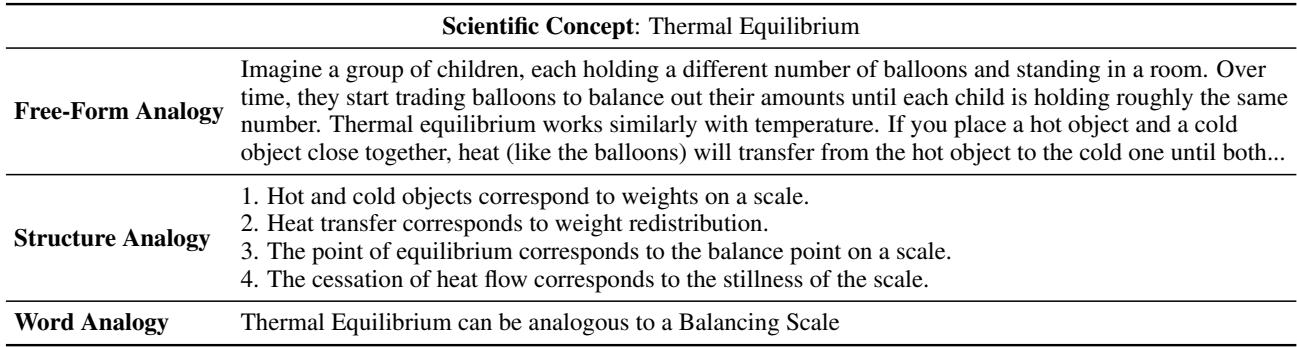

Table 1 outlines these three categories using the concept of “Thermal Equilibrium”:

- Free-Form Analogy: This is a natural language paragraph. It weaves a story or a scenario (like trading balloons or hot milk in a mug) to explain the concept intuitively. It mimics how a human tutor might speak.

- Structured Analogy: This is more formal. It explicitly maps the source domain to the target domain. It identifies specific correspondences, such as “Heat transfer corresponds to weight redistribution.” This draws on the Structure Mapping Theory of cognition.

- Word Analogy: This is the classic standardized test format (“A is to B as C is to D”). It is concise but relies heavily on the student already understanding the relationship between the analogous terms.

Methodology: Setting up the Experiment

To rigorously test this, the authors used two challenging datasets:

- ARC Challenge: A set of natural science questions designed to be hard for simple retrieval algorithms.

- GPQA: A graduate-level dataset covering biology, physics, and chemistry. These questions are so hard that even human PhD candidates usually only achieve about 65% accuracy.

The Roster

- Teachers: GPT-4, Claude-v3-Sonnet, and Mixtral-8x7B.

- Students: A mix of proprietary and open-source models, including Gemini, GPT-3.5, Llama-3-8B, and various versions of Vicuna.

The goal was to see if the Students could improve their accuracy on ARC and GPQA when aided by the Teachers’ analogies.

Experiments & Results

The results provided fascinating insights into how AI models process information and “learn.”

1. Do Analogies Actually Help?

The first research question was arguably the most important: Does this biologically inspired method actually work for silicon brains?

The answer is a resounding yes.

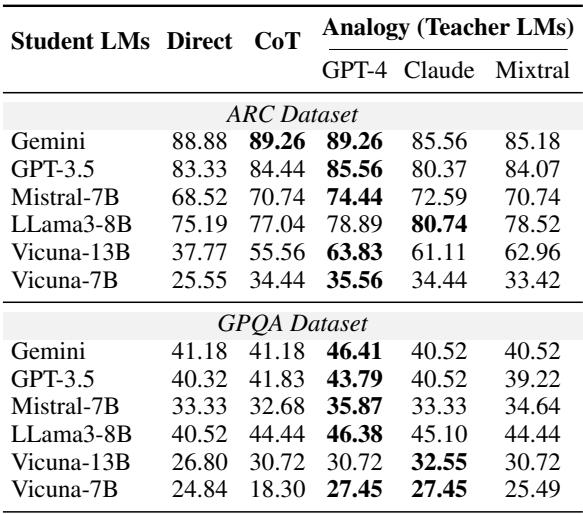

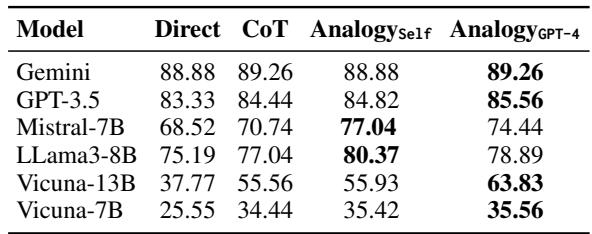

Table 2 compares the students’ performance across different strategies:

- Direct: Asking the student to answer the question directly (Zero-shot).

- CoT: Chain-of-Thought prompting (asking the model to “think step-by-step”), which is a standard method for improving reasoning.

- Analogy (Teacher LMs): Providing the student with a free-form analogy generated by a Teacher.

Key Takeaways from the Data:

- Analogies outperform standard prompting: For almost every Student LM, receiving an analogy from a Teacher (especially GPT-4) resulted in higher accuracy than Direct prompting.

- Analogies beat Chain-of-Thought (CoT): In many cases, the analogy provided a bigger boost than CoT. For example, look at Mistral-7B on the ARC dataset. It scored 68.52% directly, 70.74% with CoT, but jumped to 74.44% when given an analogy by GPT-4.

- Helping the “Slow Learners”: The impact is particularly visible on the difficult GPQA dataset. The smaller models, like Vicuna-7B, struggle immensely with these graduate-level questions. However, with the aid of an analogy, their performance improves significantly (from roughly 18-24% up to 27-35%), showing that analogies can make high-level concepts accessible to weaker models.

2. Quality vs. Utility: The “Word Analogy” Paradox

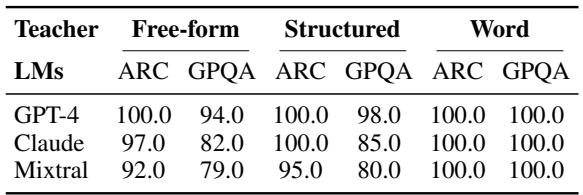

The second major finding highlights a difference between what humans think is “good” and what AI finds “useful.”

The researchers asked human annotators to rate the quality of the analogies generated by the teachers. Humans consistently rated Word Analogies very highly. They are clean, precise, and logically sound. However, when the researchers fed these analogies to the Student LMs, the results told a different story.

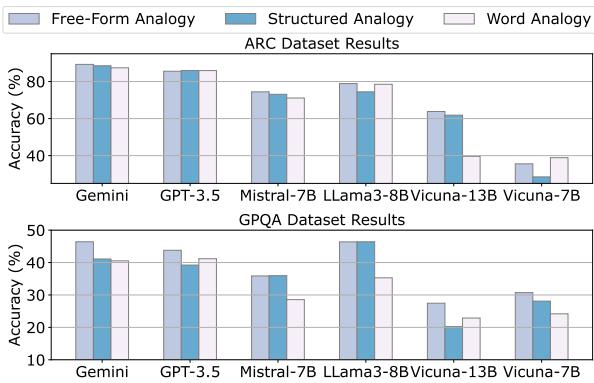

Table 3 shows the human evaluation. Notice the high scores for Word Analogies (right column). Now, let’s look at Figure 2 below, which shows the actual performance of the students when using these analogies.

In Figure 2, look at the pale bars representing Word Analogies. In almost every case, they result in lower accuracy compared to Free-Form (light blue) and Structured (medium blue) analogies.

Why does this happen? While humans appreciate the elegance of a word analogy (“Thermal Equilibrium is to Balancing Scale”), an AI trying to solve a complex physics problem needs more context.

- Free-Form analogies provide rich, descriptive text. They explain the mechanism (e.g., how the heat flows like water). This extra information acts as a knowledge injection, helping the model reason through the question.

- Word analogies are too sparse. If the Student model doesn’t fully grasp the relationship between the source and target concepts, the simple mapping doesn’t provide enough information to solve the problem.

This suggests that while strong models are great at making concise analogies, “verbose” analogies are better for teaching.

3. Can Students Teach Themselves?

Finally, the researchers explored a meta-cognitive angle. What if the Student LM generates its own analogy before answering? This is similar to a student pausing during a test to say, “Okay, this concept is kind of like…” before solving a problem.

Table 4 compares self-generated analogies (Analogy_Self) against Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and GPT-4’s analogies.

The results are encouraging for the concept of “self-learning.”

- Mistral-7B saw a massive jump using self-generated analogies (77.04%) compared to CoT (70.74%).

- In some cases, the Student’s self-generated analogy was nearly as effective, or even more effective, than the one provided by GPT-4 (see Llama3-8B: 80.37% self vs. 78.89% GPT-4).

This implies that the act of generating an analogy forces the model to access and restructure its internal knowledge, which clarifies the concept enough to answer the question correctly.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The “SCUA” task effectively demonstrates that we can borrow methods from human pedagogy to improve AI systems. Just as a good teacher uses metaphors to unlock a student’s understanding, a powerful “Teacher LM” can use free-form analogies to boost the performance of “Student LMs.”

Key Takeaways:

- Analogies are functional tools: They are not just creative writing; they measurable improve scientific reasoning in AI.

- Context is King: While short, punchy word analogies look good to humans, AI models learn better from detailed, narrative (free-form) analogies.

- Self-Teaching Potential: Models have the latent ability to improve their own reasoning by generating analogies for themselves.

This research opens the door to exciting future possibilities. We could see the development of automated tutoring systems where AI adapts its explanations based on the student’s needs. Furthermore, in the realm of “Knowledge Distillation”—where we try to make small models as smart as big ones—analogies might become a standard way to compress and transfer complex reasoning skills.

By treating AI interaction as an educational process, we find that the best way to make a model smarter might just be to tell it a story.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.11375/images/cover.png)