As Large Language Models (LMs) evolve, we are moving past simple, single-turn “chat” interfaces. Today, the cutting edge of NLP involves Language Model Programs: sophisticated pipelines where multiple LM calls are chained together to solve complex tasks. Imagine a system that retrieves information from Wikipedia, summarizes it, reasons about that summary, and then formulates a final answer. Each step is a distinct “module” requiring its own prompt.

However, this complexity introduces a massive bottleneck. How do you design prompts for a pipeline with five different stages? If the final answer is wrong, which prompt was to blame? Tuning these systems by hand (“prompt engineering”) is a tedious, trial-and-error process that becomes mathematically impossible as the number of modules grows.

In this post, we break down a significant research paper that tackles this exact problem. The researchers introduce MIPRO (Multi-prompt Instruction PRoposal Optimizer), a novel framework that automates the optimization of these pipelines. By treating instructions and few-shot demonstrations as hyperparameters, they show we can systematically improve performance—beating standard prompting methods by up to 13%.

The Problem: The Anatomy of an LM Program

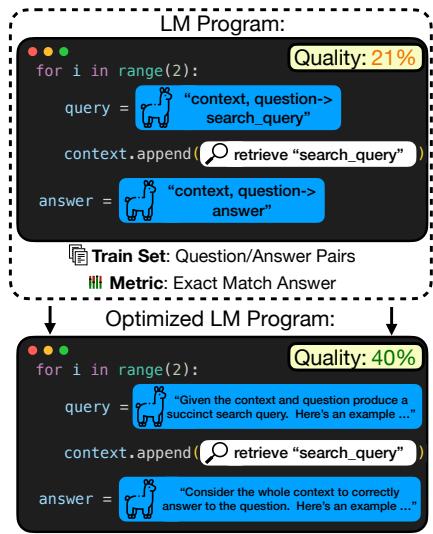

To understand the solution, we first need to understand the structure of the problem. An LM Program is a sequence of modules. For example, a multi-hop question-answering system might look like this:

- Module 1: Generate a search query based on the user’s question.

- Module 2: Read the search results and generate a second query.

- Module 3: Synthesize the final answer.

Each module has two primary “knobs” we can turn to change its behavior:

- Instructions: The specific text command (e.g., “Summarize this text concisely…”).

- Demonstrations: Few-shot examples (input/output pairs) included in the context window to show the model what to do.

Finding the perfect combination of instructions and demonstrations for every module simultaneously is the challenge.

As shown in Figure 1, a standard, unoptimized program (top) might yield a quality score of 21%. By optimizing the instructions and examples for each stage (bottom), the researchers almost doubled the performance to 40%. But how do we get from the top version to the bottom version without manual guessing?

The Mathematical Goal

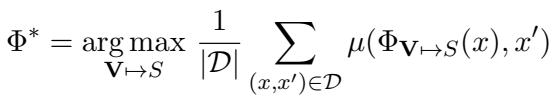

Formally, the researchers define the problem as finding a total assignment of variables (instructions and demonstrations) that maximizes a metric \(\mu\) (like accuracy or exact match) over a training dataset \(\mathcal{D}\).

This equation essentially says: “Find the set of prompts and examples (\(\Phi^*\)) that results in the highest average score across our training data.”

This problem is difficult for two main reasons:

- The Proposal Problem: The space of all possible English sentences you could use as instructions is infinite. How do we find good candidates?

- The Credit Assignment Problem: In a multi-stage pipeline, we usually only have a label for the final answer. We don’t have “gold labels” for the intermediate steps. If the pipeline fails, we don’t know if Module 1 or Module 3 was the culprit.

Strategy 1: Solving the Proposal Problem

To optimize the program, we first need a set of candidate prompts and demonstrations to test. The researchers utilize a “Proposer LM”—a separate language model tasked with generating these candidates.

Bootstrapping Demonstrations

Finding good few-shot examples is often more effective than rewriting instructions. The paper uses a technique called Bootstrap Random Search.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the process works in two steps:

- Bootstrap: We take raw inputs from the training set and run them through the program. We filter for traces where the final output was correct. Even though we didn’t label the intermediate steps, if the final answer is right, we assume the intermediate steps were likely good enough. These traces become our candidate demonstrations.

- Search: We randomly sample different combinations of these bootstrapped demonstrations to see which set yields the highest performance.

Grounding Instructions

To generate instruction candidates, the researchers don’t just ask an LM to “write a better prompt.” They use Grounding. They feed the Proposer LM specific context:

- Data Summaries: A description of the patterns found in the dataset.

- Program Code: The actual code of the pipeline so the model understands the flow.

- Trace History: Previous instructions that worked or failed.

This context allows the Proposer LM to write instructions that are actually tailored to the specific task nuances.

Strategy 2: Solving the Credit Assignment Problem

Once we have a pile of candidate instructions and demonstrations, how do we figure out which combination works best? The paper explores two major approaches.

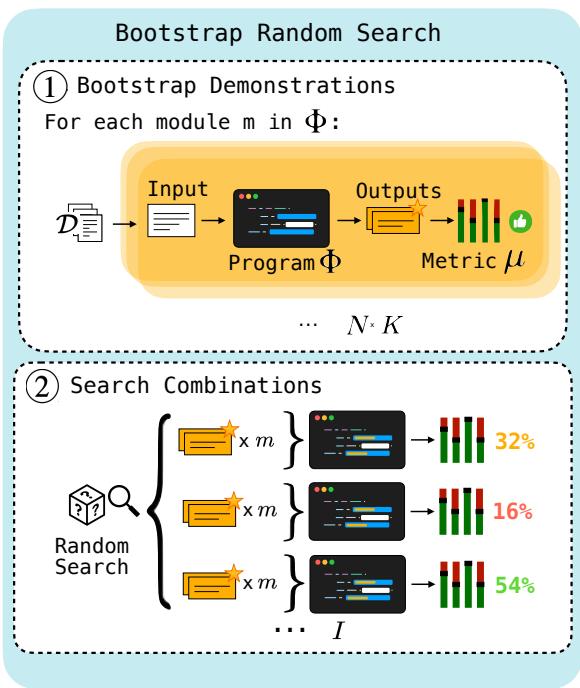

Approach A: History-Based Optimization (OPRO)

One method, adapted from prior work called OPRO, asks the Language Model to act as the optimizer.

In Module-Level OPRO (Figure 3), the optimizer keeps a history of previous instructions and their resulting scores. It feeds this history back into the Proposer LM and essentially asks, “Here is what we tried and how well it worked; please propose a better instruction.”

While elegant, this has limitations. As the history grows, the context window fills up, and LMs can struggle to infer complex correlations between a specific change in wording and a marginal increase in score.

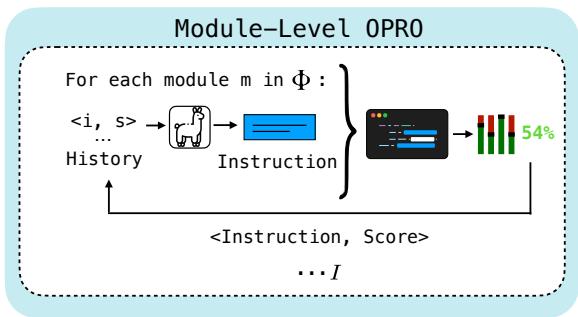

Approach B: Surrogate Models (The MIPRO Approach)

This leads to the paper’s main contribution: MIPRO. Instead of asking an LM to do the math, MIPRO uses a dedicated Bayesian surrogate model.

MIPRO decouples the proposal phase from the selection phase.

- Proposal: It generates a large pool of candidate instructions and demonstrations using the grounding techniques mentioned earlier.

- Optimization: It uses a Bayesian optimization algorithm (specifically Tree-Structured Parzen Estimator, or TPE) to navigate the search space.

The Solution: MIPRO (Multi-prompt Instruction PRoposal Optimizer)

MIPRO is designed to handle the noise and complexity of multi-stage programs.

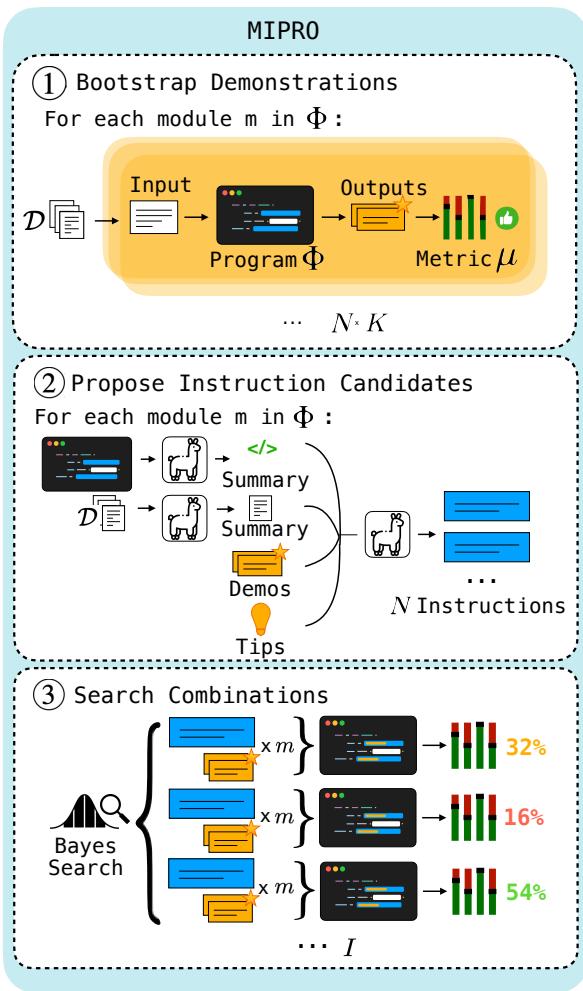

Figure 4 outlines the full MIPRO pipeline:

- Bootstrap: Generate effective few-shot demonstrations from the training data.

- Propose: Use a Grounded Proposer LM to generate diverse instruction candidates for every module in the pipeline.

- Search (The Brains): This is where MIPRO shines. It treats the choice of instruction (from the proposed set) and the choice of demonstrations as discrete variables. It uses the Bayesian surrogate model to predict which combination will perform best.

Crucially, MIPRO uses minibatching. Instead of running the full training set for every trial (which is expensive), it evaluates candidates on small batches of data to quickly update its beliefs about which parameters are working. This allows it to explore the search space much more efficiently than random search.

Experiments and Results

The researchers benchmarked these optimizers on seven diverse tasks, including HotPotQA (multi-hop reasoning), HoVer (fact verification), and ScoNe (logical negation).

They compared three primary settings:

- Zero-Shot: Optimizing instructions only.

- Few-Shot: Optimizing demonstrations only.

- Joint (MIPRO): Optimizing both simultaneously.

Key Finding 1: MIPRO generally outperforms baselines

By optimizing both instructions and demonstrations jointly, MIPRO achieved the best results on 5 out of 7 tasks.

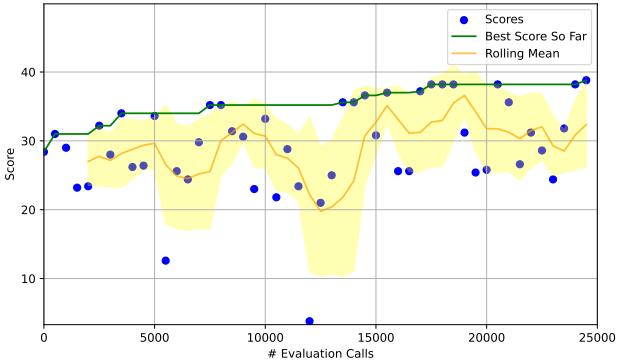

Looking at the HotPotQA results (Figure 9), we can see the performance trajectory. The bottom-right graph (MIPRO) shows a steady climb in performance (green line), eventually surpassing the other methods. The “Rolling Mean” (orange area) indicates that the optimizer is consistently finding better configurations as it learns.

Key Finding 2: Demonstrations are often more powerful than Instructions

For many tasks, simply finding the right few-shot examples (Bootstrapping) provided a bigger boost than rewriting the prompt text.

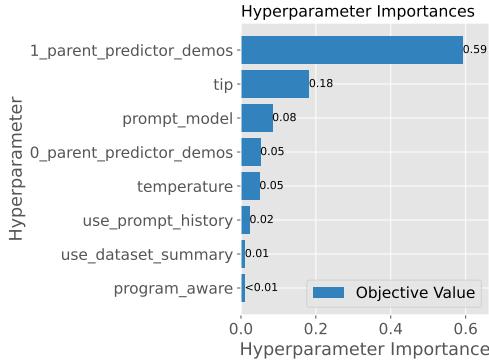

The Bayesian model in MIPRO allows us to inspect “feature importance”—essentially, which variables mattered most for the score. In Figure 6, we see that for HotpotQA, the _parent_predictor_demos (the choice of demonstrations) had a significantly higher importance score (0.59) than the tip or the temperature of the model.

Key Finding 3: Instructions matter for “Conditional” Logic

However, instructions are not useless. The researchers created a “HotPotQA Conditional” task with complex formatting rules (e.g., “if the answer is a person, use lowercase”). In this scenario, few-shot examples weren’t enough to teach the rule. The optimizer had to refine the instruction text to get high performance.

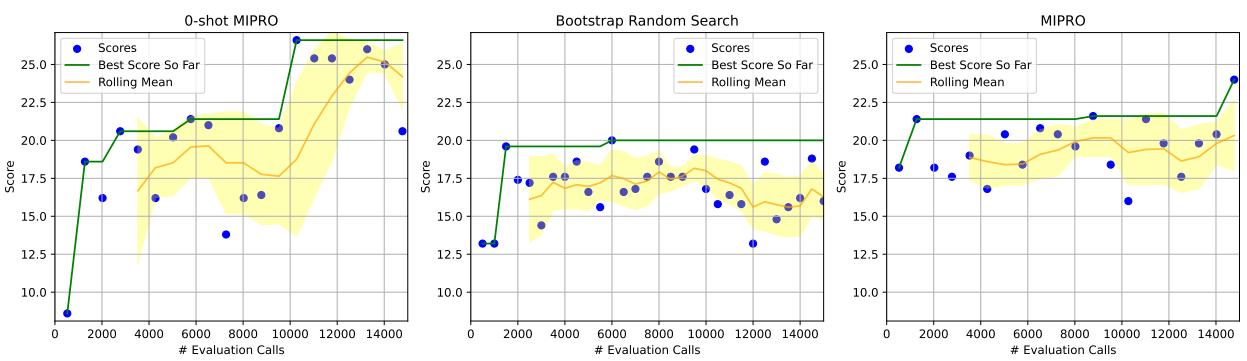

In Figure 11 (HotPotQA Conditional), notice how the 0-Shot MIPRO (left) and MIPRO (right) graphs achieve high scores, while the Bootstrap Random Search (middle)—which only optimizes demonstrations—struggles significantly. This proves that when the task involves complex logic or constraints, instruction optimization is non-negotiable.

Conclusion and Implications

The transition from manual prompt engineering to automated optimization is inevitable. As LM programs grow in complexity, humans simply cannot intuit the optimal combination of prompts for a 10-step pipeline.

This paper provides a robust framework for this automation. The key takeaways for students and practitioners are:

- Don’t just tune the prompt text: The choice of few-shot demonstrations is often the highest-leverage hyperparameter.

- Use Grounding: When asking an LM to write prompts, give it data summaries and code context.

- Joint Optimization: The interaction between instructions and demonstrations is complex. Optimizers like MIPRO that tune them together yield the best results.

By treating natural language prompts as optimizing weights in a network, we are moving toward a future where “programming” LMs looks less like writing essays and more like training neural networks.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.11695/images/cover.png)