If you have ever spent time in the comment section of a social media platform, you have likely encountered an argument that just felt wrong. It wasn’t necessarily that the facts were incorrect, but rather that the way the dots were connected didn’t make sense.

Perhaps someone argued, “If we don’t ban all cars immediately, the planet is doomed.” You know this is an extreme stance that ignores middle-ground solutions, a classic False Dilemma. Or maybe you read, “My uncle ate bacon every day and lived to be 90, so bacon is healthy.” This is a Faulty Generalization—taking a single data point and applying it to the whole population.

In the world of Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Artificial Intelligence, we have gotten quite good at detecting these fallacies. We can train models to look at a sentence and slap a label on it: “Ad Hominem,” “Slippery Slope,” or “Red Herring.”

But here is the catch: knowing that an argument is flawed is not the same as understanding why it is flawed. Labeling is useful, but it doesn’t help a student learn better writing, nor does it help an AI explain its reasoning.

In this deep dive, we will explore a fascinating research paper titled “Flee the Flaw: Annotating the Underlying Logic of Fallacious Arguments Through Templates and Slot-filling.” The researchers propose a novel way to look under the hood of bad arguments, moving beyond simple labels to mapping out the broken logic itself.

The Problem: The “Black Box” of Fallacy Detection

Current computational argumentation research focuses heavily on two things:

- Scoring Quality: Giving an essay a 7/10 based on persuasiveness.

- Type Labeling: Categorizing fallacies (e.g., identifying a “Strawman” argument).

While useful, these approaches treat the argument as a flat sequence of words. They don’t explicate the structure of the reasoning error.

Imagine a teacher grading a paper. If the teacher just writes “Illogical” in the margin, the student learns nothing. If the teacher writes, “You are assuming that because event A happened before event B, A caused B, which isn’t proven,” the student gains insight. The researchers behind “Flee the Flaw” (FtF) wanted to create a computational framework that mimics that second, more detailed explanation.

The Background: Argumentation Schemes

To understand how the researchers solved this, we first need to understand how we structure good arguments. In argumentation theory, we often use Argumentation Schemes. One of the most common schemes is the Argument from Consequence.

It looks like this:

- Premise: If [Action A] is brought about, [Consequence C] will occur.

- Value Judgment: [Consequence C] is bad (or good).

- Conclusion: Therefore, [Action A] should not (or should) be brought about.

This is the backbone of most persuasive writing. “You should study (A) because you will get a good job (C).” “You shouldn’t smoke (A) because it causes cancer (C).”

The researchers realized that many informal fallacies are actually corrupted versions of this specific scheme. They act like valid arguments from consequence, but the link between the Action and the Consequence is broken or manipulated.

The Core Method: Explainable Templates

The heart of this paper is the introduction of Fallacy Templates. The researchers didn’t just want to categorize arguments; they wanted to fill in the blanks (slots) to reveal the flaw.

They built upon existing “Argument Templates”—structured representations of reasoning—and added a critical new component: Premise P’ (P-prime).

- P (The Standard Premise): The stated reason (e.g., “This action causes this result”).

- P’ (The Fallacious Premise): The implicit, flawed logic that acts as the bridge. This premise explains why the argument fails.

Visualizing the Logic

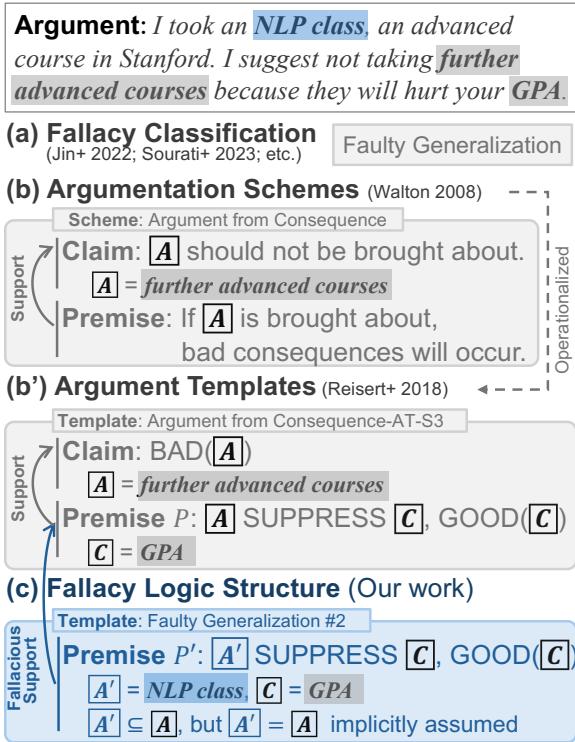

Let’s look at how this works in practice. Consider an argument where someone advises against taking advanced courses because they had a bad experience in one specific class.

In Figure 1 above, we see the transformation of the analysis:

- (a) Fallacy Classification: Previous systems would simply label this “Faulty Generalization.”

- (b) Argument Scheme: It identifies the core structure: “If you take advanced courses (A), it hurts your GPA (C).”

- (c) Fallacy Logic Structure (The New Contribution): This is where the magic happens. The template identifies a hidden premise (\(P'\)).

- The writer implies that their specific “NLP Class” (\(A'\)) is a stand-in for all “Advanced Courses” (\(A\)).

- The fallacy lies in the assumption that \(A' = A\).

By explicitly annotating this \(A'\) (the subset), the system can explain the error: “The argument is a faulty generalization because it treats a single NLP class as representative of all advanced courses.”

The Inventory of Templates

The researchers focused on four common “defective induction” fallacies. These are arguments where the premises provide some support, but not enough to justify the conclusion.

- Faulty Generalization: Drawing a broad conclusion from a small sample.

- False Dilemma: Presenting two options as the only possibilities.

- False Causality: Assuming correlation implies causation.

- Fallacy of Credibility: Appealing to an irrelevant authority.

For each of these, they designed specific templates.

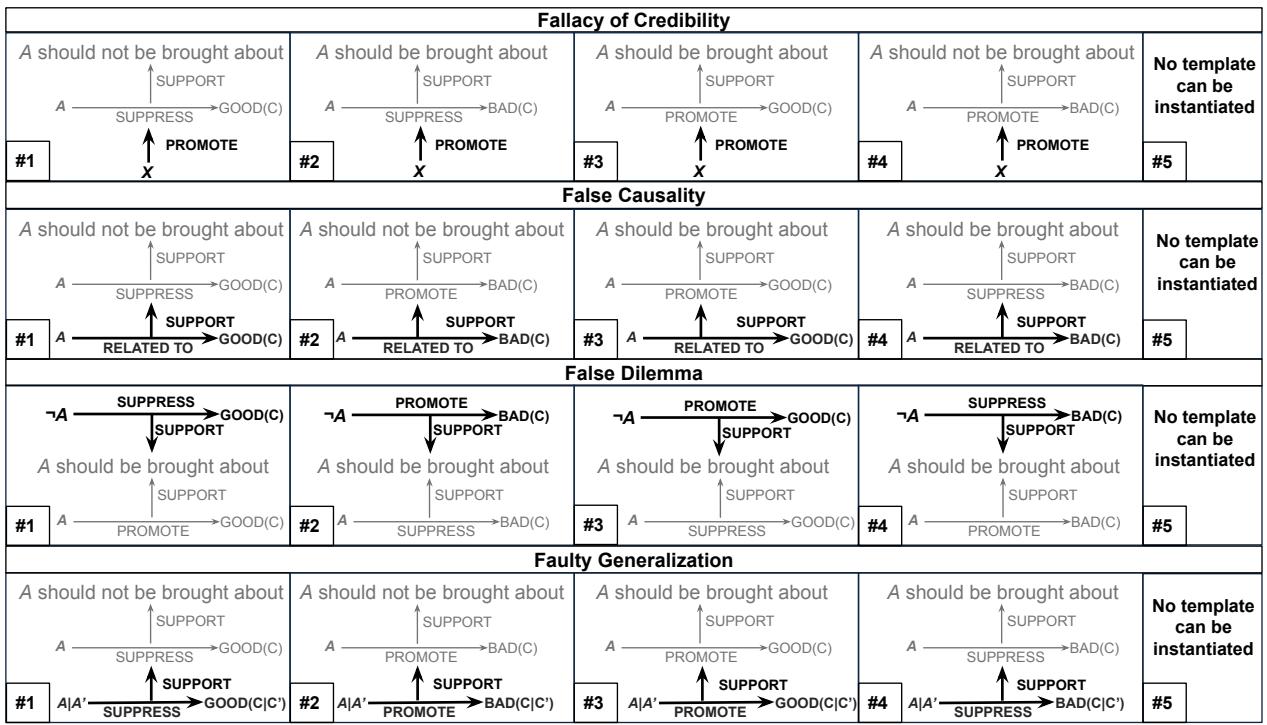

As shown in Figure 2, the templates are flexible. They can handle positive arguments (“Do this because it promotes good things”) and negative arguments (“Don’t do this because it suppresses good things”). They essentially create a “mad-libs” style structure for logic.

Let’s break down each fallacy type using the paper’s specific schemas.

1. Faulty Generalization

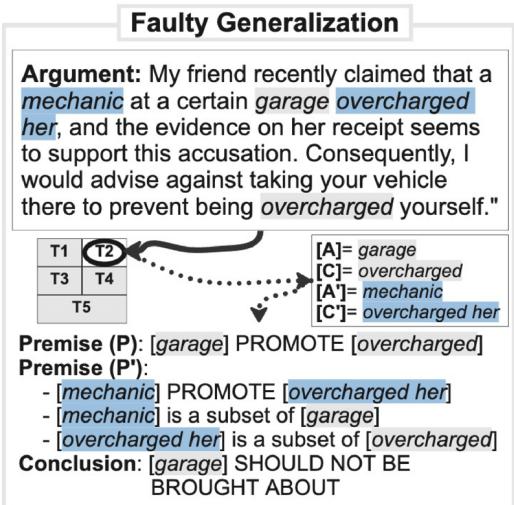

This occurs when a sample (\(A'\)) is used to represent a whole population (\(A\)).

In Figure 3, the argument is: “Don’t go to that garage (\(A\)) because a mechanic (\(A'\)) there overcharged my friend.”

- The Flaw: The template captures that \(A'\) (the mechanic) is just a subset of \(A\) (the garage).

- The Logic: \(A'\) promotes a bad consequence, but the argument incorrectly transfers that property to the whole garage \(A\).

2. Fallacy of Credibility

This is often called “Appeal to Authority.” It happens when the person supporting the argument (\(X\)) isn’t actually an expert on the topic (\(A\)).

![Diagram for Fallacy of Credibility. The example argument is “My best friend tweeted about the health benefits of pizza…”. The analysis identifies “My best friend” as [X], “pizza” as [A], and “health benefits” as [C]. The template reveals the disconnect between the source’s authority and the claim.](/en/paper/2406.12402/images/009.jpg#center)

In Figure 5, the example is hilarious but structurally sound: “My best friend (\(X\)) tweeted that pizza (\(A\)) has health benefits (\(C\)), so we should eat it.”

- The Flaw: The template highlights the variable \(X\) (Best Friend).

- The Logic: \(X\) is promoting the idea that \(A\) leads to \(C\). The fallacy template isolates the source (\(X\)) so we can evaluate if they are actually credible (spoiler: best friends usually aren’t nutritionists).

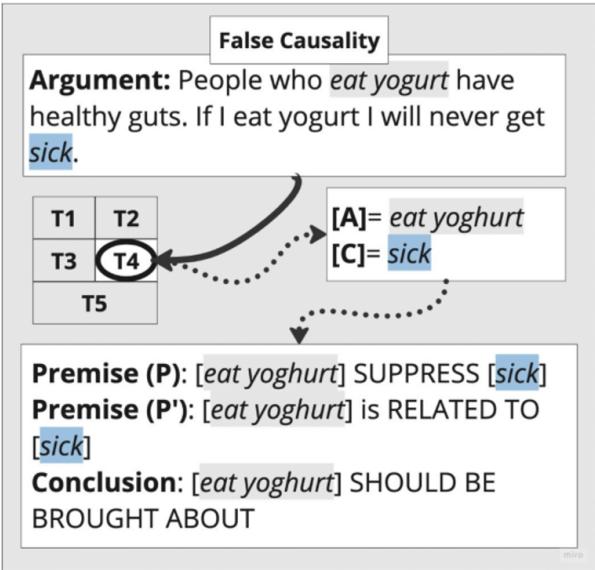

3. False Causality

This is the classic “Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc.” Just because two things are related (\(RELATED\_TO\)) doesn’t mean one causes the other (\(SUPPRESS/PROMOTE\)).

In Figure 6, the argument claims that because people who eat yogurt (\(A\)) have healthy guts, eating yogurt ensures you will never get sick (\(C\)).

- The Flaw: The template separates the observation (\(A\) is related to \(C\)) from the causal claim (\(A\) suppresses sickness). It highlights the leap in logic.

4. False Dilemma

This is an “Either/Or” fallacy. It forces a choice between two options, ignoring others.

![Diagram for False Dilemma. The example argument is “We either have to cut taxes or leave a huge debt…”. The analysis identifies “cut taxes” as [A] and “leave debt” as [C]. It maps out the limited “either-or” structure imposed by the argument.](/en/paper/2406.12402/images/011.jpg#center)

In Figure 7, the argument is “We either cut taxes (\(A\)) or leave debt (\(C\)).”

- The Flaw: The template maps out the premises: \(A\) suppresses \(C\), and not doing \(A\) promotes \(C\). This structure exposes the rigid dependency created by the writer, allowing an analyst to ask: “Is there really no Option D?”

Building the “Flee the Flaw” Dataset

Designing templates is one thing; applying them to real-world data is another. The researchers created the Flee the Flaw (FtF) dataset.

They started with an existing dataset called LOGIC, which contained fallacious arguments about climate change and other topics. They selected 400 arguments and asked human annotators to apply the new templates.

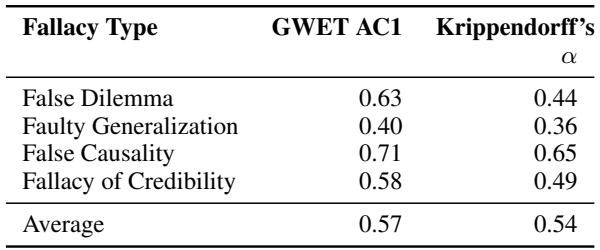

This was not a simple task. Logic is subjective. The researchers measured Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA)—essentially, how often two humans independently picked the same template and the same text spans.

As Table 1 shows, they achieved a Krippendorff’s \(\alpha\) of 0.54. In the world of linguistic annotation, this is considered a “high agreement” for such a complex, high-level cognitive task. It proves that the templates are robust enough that different people understand them in the same way.

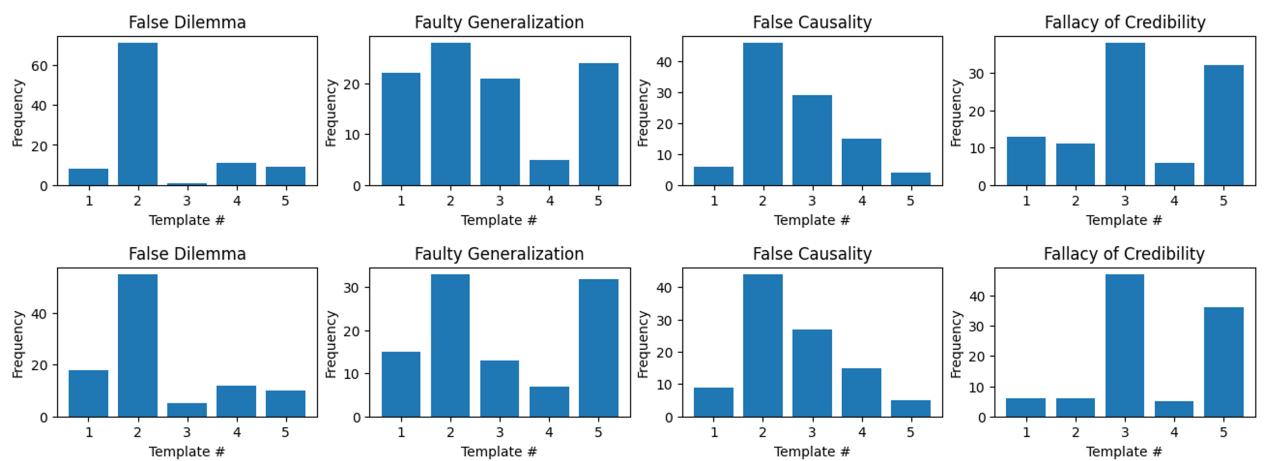

However, the distribution wasn’t perfectly even.

Figure 4 reveals an interesting reality about real-world arguments: they tend to follow specific patterns. For “False Dilemma” and “False Causality,” annotators heavily favored Template #2. This suggests that while there are many theoretical ways to construct a fallacy, humans tend to reuse the same few rhetorical structures.

Experiments: Can AI “Flee the Flaw”?

The ultimate test was to see if current state-of-the-art Large Language Models (LLMs) could perform this annotation automatically.

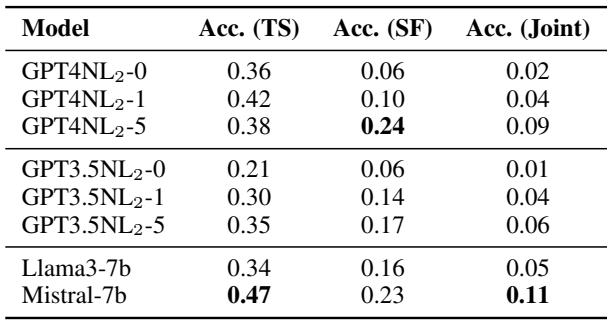

The researchers set up a two-part task for models like GPT-4, Llama-3, and Mistral-7B:

- Template Selection: Can the AI pick the right logic map? (e.g., Template #1 vs #2).

- Slot-Filling: Can the AI identify the exact words in the text that correspond to the Action (\(A\)), Consequence (\(C\)), and other variables?

They used Few-Shot Prompting (giving the AI a few examples) and even tried Fine-Tuning (training the model specifically on this data).

The results were… humbling.

Table 4 presents the “Joint Accuracy”—the percentage of times the AI got both the template and the slot-filling correct.

- GPT-4 (5-shot): 9% accuracy.

- Mistral-7B: 11% accuracy.

- GPT-3.5: 6% accuracy.

What does this mean? These low numbers indicate that while LLMs are great at generating text and answering general questions, they struggle significantly with structured logical analysis. They can “vibe check” an argument to say it’s bad, but asking them to pinpoint the exact logical variables (\(A\), \(C\), \(P'\)) causes them to hallucinate or misinterpret the text.

The error analysis showed that models often:

- Selected the “None of the above” template (Template #5) because they couldn’t map the logic.

- identified the correct template but filled the slots with the wrong words (e.g., confusing the cause with the effect).

Conclusion and Implications

The “Flee the Flaw” paper represents a significant step forward in Computational Argumentation. It attempts to move the field from shallow detection to deep explication.

Key Takeaways:

- Logic has Shape: Fallacies aren’t just abstract errors; they have recurring structures that can be templated.

- Humans can see it: With the right guidelines, humans can agree on the underlying logic of a bad argument.

- Machines can’t (yet): This task remains a “Grand Challenge” for AI. The nuance required to distinguish between a standard premise and a fallacious implicit premise is currently beyond the capabilities of even models like GPT-4.

Why does this matter? If we can solve this, the applications are powerful. Imagine a writing tutor that doesn’t just put a red “X” on your essay but says, “You are using a False Causality here. You showed that X and Y are related, but you haven’t proven that X causes Y.”

Or consider fact-checking. Instead of just flagging a tweet as “Misinformation,” a system could generate a breakdown: “This post uses a False Dilemma logic, presenting only two scary options while ignoring accurate data from Z.”

By forcing us to look at the structure of flaws, this research paves the way for AI that doesn’t just read, but actually reasons.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.12402/images/cover.png)