Since the transformer architecture burst onto the scene with the famous paper “Attention Is All You Need,” the philosophy in Deep Learning has often leaned towards “more is better.” More data, more layers, more parameters. However, when it comes to alignment—the process of ensuring Large Language Models (LLMs) are helpful, honest, and harmless—it turns out that using everything might actually be the problem.

In a fascinating research paper titled “Not Everything is All You Need: Toward Low-Redundant Optimization for Large Language Model Alignment,” researchers from Renmin University of China and Beihang University challenge the status quo. They propose a counter-intuitive idea: by identifying and training only the most relevant neurons (and ignoring the rest), we can align models better, faster, and more effectively than by updating every single parameter.

In this post, we will dissect their method, known as ALLO (ALignment with Low-Redundant Optimization). We will explore why full-parameter tuning often introduces noise, how to surgically identify the “alignment neurons,” and how to split training into “forgetting” and “learning” stages.

The Problem: The Noise of Full-Parameter Tuning

To align an LLM, we typically use methods like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) or Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). These methods take a pre-trained model and fine-tune it on pairs of “good” (positive) and “bad” (negative) responses.

The standard approach is to update all the trainable parameters in the model to maximize the likelihood of the good response and minimize the bad. But here lies the issue: LLMs are massive. When you update all parameters to align with a specific preference dataset, the model inevitably overfits to superficial styles or unexpected patterns in that specific data.

The researchers hypothesize that redundancy exists in LLMs. Not every neuron is responsible for understanding human preference. By forcing irrelevant neurons to update, we introduce noise and degrade performance.

Evidence of Redundancy

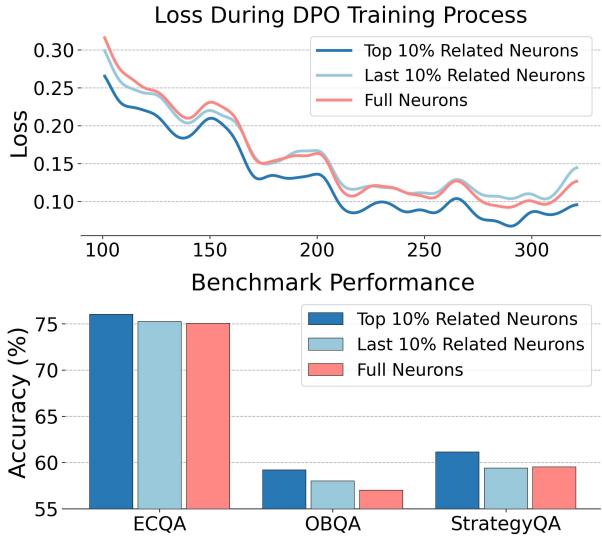

To prove this, the authors conducted an empirical study. They compared the training loss of a model where all neurons were updated versus a model where only the top-10% most relevant neurons were updated.

As shown in Figure 1 above, the results are striking. The red line represents the loss when training full neurons. The blue line represents the loss when training only the top-10% of related neurons.

Notice that the blue line is significantly lower, indicating better convergence. Furthermore, the bar charts show that the top-10% approach achieves higher accuracy on benchmarks like ECQA and QASC. This suggests that the other 90% of neurons were essentially dead weight—or worse, active saboteurs—during the alignment process.

The Solution: The ALLO Framework

Based on this discovery, the authors propose ALLO. The core philosophy of ALLO is low-redundant optimization. Instead of a shotgun approach, it uses a sniper rifle. It focuses only on the neurons that matter and the tokens that carry the strongest signal.

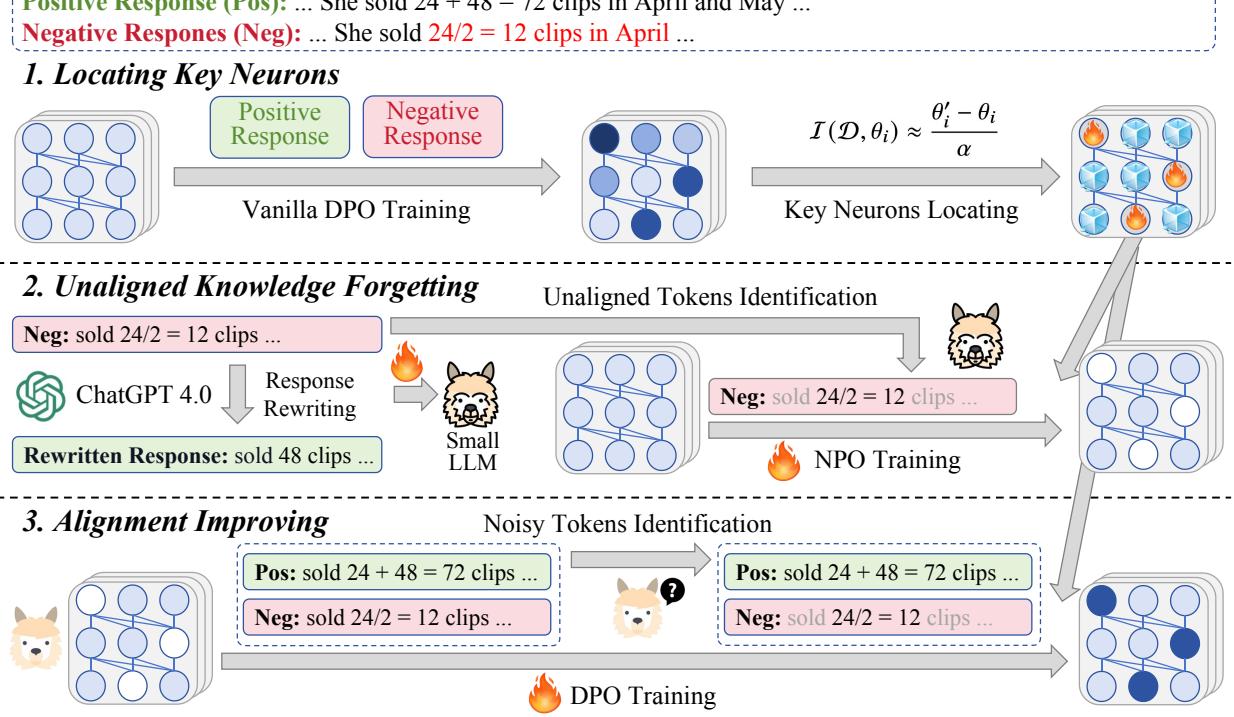

The framework operates in three distinct steps:

- Locating Key Neurons: Identifying which parts of the brain need to change.

- Unaligned Knowledge Forgetting: Explicitly removing bad habits.

- Alignment Improving: Reinforcing good behaviors while filtering out noise.

Let’s look at the high-level architecture:

Now, let’s break down each stage mathematically and conceptually.

Stage 1: Locating Key Neurons

How do you know which neuron is “important” for alignment? The researchers used a gradient-based strategy.

First, they train a “reference model” on the human preference data using standard DPO for one epoch. This is essentially a dry run. They then look at how much the weights of the model changed. If a neuron’s weight shifted significantly during this dry run, it implies that the neuron is highly sensitive and relevant to the alignment data.

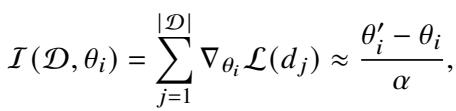

The importance of a neuron (\(\theta_i\)) is estimated by the accumulation of gradients, which can be approximated by the difference between the updated weight (\(\theta'_i\)) and the original weight (\(\theta_i\)), divided by the learning rate (\(\alpha\)):

Once the importance scores are calculated, the researchers sort them and select the top-\(k\) percent. These are the Key Neurons. Throughout the rest of the ALLO process, the optimization is applied only to these selected neurons, while the rest are frozen.

Stage 2: Unaligned Knowledge Forgetting

Alignment isn’t just about learning what to do; it’s about unlearning what not to do. LLMs often harbor “unaligned knowledge”—biases, hallucinations, or harmful outputs ingrained during pre-training.

Most methods try to learn positive and suppress negative simultaneously. ALLO separates these concerns. In this stage, the goal is purely to forget the negative patterns.

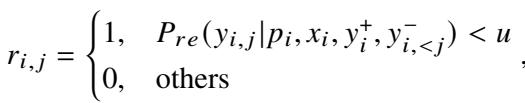

Identifying the “Bad” Tokens

Not every word in a “bad” response is actually bad. If a model generates a toxic sentence, the grammar might be perfect (we don’t want to unlearn grammar), but the toxic adjectives are the problem.

To solve this, ALLO uses a Token-Level Reward Model. They employ a teacher model (like GPT-4) to rewrite the negative response into a positive one with minimal edits. They then train a small reward model to compare the original negative response with the corrected version.

If a token in the negative response leads to a low probability of generating the corrected version, it is flagged as an “unaligned token.”

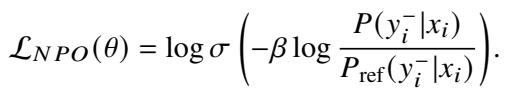

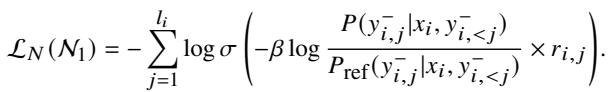

Fine-Grained Unlearning (NPO)

With the bad tokens identified, ALLO applies Negative Preference Optimization (NPO). This algorithm focuses specifically on minimizing the likelihood of generating those specific negative tokens.

The standard NPO loss looks like this:

However, ALLO modifies this to be low-redundant. It applies the loss only to the specific tokens identified as unaligned (using the reward \(r_{i,j}\) as a weight) and updates only the key neurons identified in Stage 1.

By doing this, the model surgically removes the “bad” knowledge without damaging its general linguistic capabilities.

Stage 3: Alignment Improving

Now that the model has “forgotten” the bad habits, it’s time to reinforce the good ones. For this, ALLO uses Direct Preference Optimization (DPO).

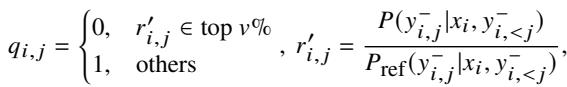

Filtering Noisy Tokens

Just as negative responses have neutral tokens, positive responses have “noisy” tokens—words that are acceptable but don’t strongly contribute to the alignment signal. If a token has an abnormally high reward score (a large gap between the policy model and the reference model), it might be an outlier or “noise” that destabilizes training.

ALLO calculates a dynamic weight (\(q_{i,j}\)) for tokens in the DPO process. If a token’s reward score is too high (in the top percentile), it is masked out (weight = 0).

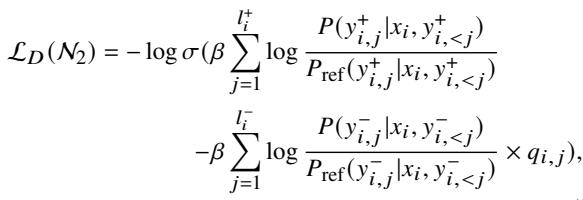

Fine-Grained Learning

Finally, the model is trained using a modified DPO objective. This objective incorporates the “noisy token” mask and, crucially, continues to update only the specific subset of key neurons (\(N_2\)).

This completes the pipeline. The model has been cleaned of bad habits and fine-tuned on good habits, all while touching only a fraction of its total parameters.

Experiments and Results

The theory sounds solid, but does it work? The researchers tested ALLO across three major categories of tasks:

- Question Answering (QA): ECQA, QASC, OpenBookQA, StrategyQA.

- Mathematical Reasoning: GSM8k, MATH, etc.

- Instruction Following: AlpacaEval 2.0, Arena-Hard.

They compared ALLO against strong baselines including standard SFT, DPO, PPO (the method used for ChatGPT), and recent variants like SimPO.

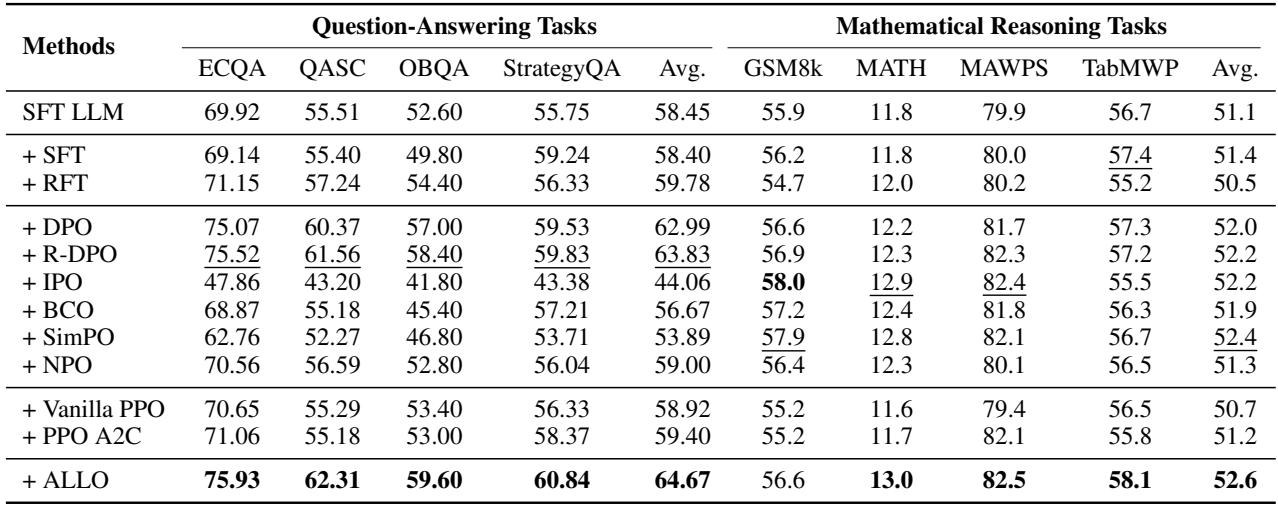

Performance on Reasoning and Math

In reasoning-heavy tasks, precision is key. As seen in Table 2 below, ALLO (bottom row) consistently achieves the highest average scores.

On the ECQA dataset, ALLO achieved 75.93%, beating vanilla DPO (75.07%) and significantly outperforming SFT (69.14%). In mathematical reasoning (GSM8k, MATH), ALLO also secured the top spot. This indicates that by reducing parameter redundancy, the model preserves its reasoning logic better than full-parameter updates, which might overwrite critical logic circuits.

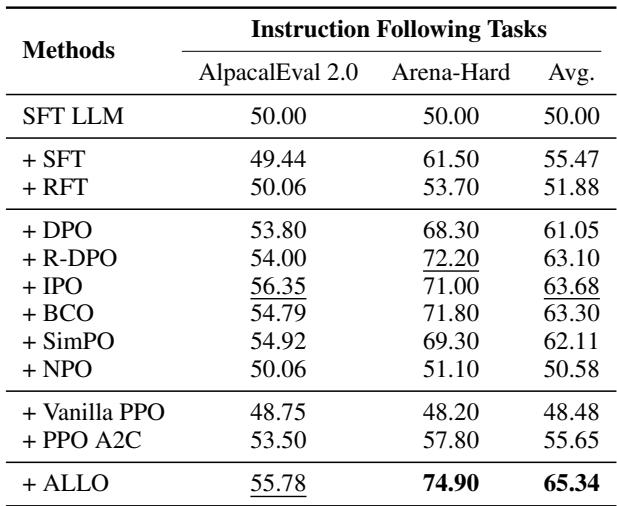

Performance on Instruction Following

Instruction following is perhaps the most direct test of “alignment.” Can the model act as a helpful assistant?

Table 3 shows the win rates on AlpacaEval and Arena-Hard. ALLO achieves a massive 74.90% on Arena-Hard, significantly outperforming DPO (68.30%) and SimPO (69.30%). The average improvement is substantial, demonstrating that the “forget-then-learn” strategy combined with neuron pruning results in a much more helpful assistant.

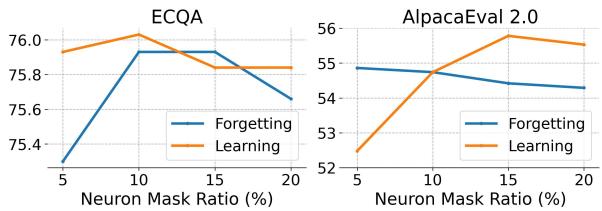

Analysis: How Much Should We Prune?

One of the most critical hyper-parameters in ALLO is the Neuron Mask Ratio—what percentage of neurons should we actually train?

The authors varied this ratio to find the “sweet spot.”

Figure 4 reveals an interesting trend (an inverted U-shape):

- Too few neurons (5%): The model lacks the capacity to adapt to the new alignment data.

- Too many neurons (20%+): Performance starts to drop again.

The peak performance sits around 10% to 15%. This validates the core premise of the paper: adding more trainable parameters beyond a certain point yields diminishing returns and eventually hurts performance due to noise and interference.

Conclusion

The “Not Everything is All You Need” paper provides a compelling argument for restraint in the era of massive LLMs. It highlights that alignment is a surgical procedure, not a blunt force transformation.

By identifying the specific neurons responsible for task alignment and isolating the specific tokens that represent unaligned behavior, ALLO achieves state-of-the-art results with greater efficiency.

Key Takeaways:

- Redundancy is real: 90% of neurons may not need updating for specific alignment tasks.

- Forget before you learn: Explicitly unlearning negative behaviors (via NPO) clears the path for better alignment.

- Filter the noise: Not all data points in a dataset are useful; dynamic filtering of tokens prevents overfitting.

As models continue to grow larger, methods like ALLO that focus on efficiency and low-redundancy will likely become the standard for turning raw computational power into helpful, human-aligned intelligence.

](https://deep-paper.org/en/paper/2406.12606/images/cover.png)